Abstract

Study design:

Performance improvement initiative.

Objectives:

To improve efficiency of spinal cord rehabilitation by reducing length of stay (LOS) while maintaining or improving patient outcomes.

Setting:

Academic hospital in Canada.

Methods:

LOS benchmarking was completed using national comparator data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Clinical decision-making tools were developed to support implementation and sustainability. A standardized ‘tentative discharge date’ calculator was created to establish objective LOS targets. Defined discharge criteria and an accompanying clinical decision tree were developed to support team decision making and improve transparency. A revised patient census tool was also implemented to improve team communication and facilitate data collection. The initiative was implemented in March 2010 and the following metrics were evaluated: LOS, Functional Independence Measure (FIM) change and FIM efficiency.

Results:

Outcomes are reported for the 2010/11 fiscal year, and compared with the two prior fiscal years. Mean LOS for individuals undergoing initial inpatient rehabilitation was 71.5 days for 2010/11, a 14 and 17% reduction compared with the 2008/09 and 2009/10 fiscal years, respectively. While LOS decreased, FIM change increased 9 and 16% compared with 2008/09 and 2009/10, respectively. Similarly, FIM efficiency increased 54 and 32% compared with 2008/09 and 2009/10.

Conclusion:

The use of benchmarking and decision support tools improved rehabilitation efficiency while increasing standardization in practice and transparency in LOS determination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rehabilitation of spinal cord injury (SCI) is challenging and resource intensive. Inpatient care is particularly expensive.1, 2 Given today’s health care environment and fiscal constraints, spinal cord programs must provide care in the most efficient manner possible while at the same time maximizing client outcomes. Reducing lengths of stay (LOS), while maintaining outcomes, leads to substantial cost savings, particularly if achieved without allocating additional resources. Additional benefits include (1) providing inpatient rehabilitation to more individuals, and (2) enhancing patient flow within health care systems due to the increased bed availability and expedited transfers from acute care. Prior studies have shown that lack of rehabilitation beds leads to excess and unneeded bed occupancy days in acute care.3

In response to the challenges of (1) suboptimal patient flow across the health care continuum and (2) increasing fiscal pressures (programmatic and provincial), the Spinal Cord Rehabilitation Program of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute initiated an efficiency exercise to reduce mean LOS for initial rehabilitation while maintaining or improving rehabilitation outcomes. It is hoped that this information will benefit other spinal cord rehabilitation programs faced with similar challenges.

Methods

Benchmarking and LOS targets

A benchmarking exercise used data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). All Canadian provinces except the three Northern territories and Quebec, submit data to the National Rehabilitation Reporting System (NRS). Submission is mandated in Ontario and a region of Manitoba, while other jurisdictions submit inpatient rehabilitation data on a voluntary basis. The data and reporting system are maintained by CIHI. Information includes LOS and rehabilitation outcomes (for example, Functional Independence Measure (FIM) change and efficiency).

Benchmarking results were used to set LOS targets and frame the communication strategy (see below). Previously, projected LOS was largely subjective and based on clinician experience and judgment. The Spinal Cord Rehabilitation Program staffed 57 inpatient beds and care was provided on three 19 bed units with distinct interdisciplinary teams. LOS varied across units despite the same case mix. A standardized process was therefore needed to increase objectivity and transparency, and ensure consistency across units.

The NRS categorizes individuals with spinal cord lesions into Rehabilitation Patient Groups (RPGs) based on the nature of the pathology (neurological/traumatic SCI/non-traumatic SCI) and the admission motor FIM score (further subdivided by age for some groups) (Figure 1). Stroke patients have also been categorized using RPGs.4 The Australian National Subacute and Nonacute Patient Casemix Classification used a similar approach to categorize stroke and SCI patients.5, 6, 7, 8 Casemix groupings employed in the United States for medicare reimbursement also take into account functional status and age.9

NRS Rehabilitation Patient Groups (RPGs) and National Averages for LOS. NRS RPG classifications are presented along with mean LOS for each RPG group using national data. Program LOS targets were set to align with national averages. Source: NRS, CIHI 2008-09. A full color version of this figure is available at the Spinal Cord journal online.

RPG methodology uses 12 items to calculate the admission motor FIM score (excludes tub/shower transfers). Examples of neurological conditions include Guillain Barre syndrome or multiple sclerosis with predominant spinal cord involvement. Non-traumatic SCI includes spinal cord infarcts, tumors or epidural abscesses, among other causes. Traumatic SCI includes etiologies such as falls and motor vehicle collisions.

Patients admitted for initial rehabilitation were categorized according to their corresponding NRS RPG (Figure 1). A target LOS was set for each individual using the national average (NRS, CIHI 2008-9 data) for his or her RPG. Target LOS was not rigid and could be adjusted as indicated by individual client needs. The intent, however, was to provide clinical teams with objective targets. If after discussion the team felt the individual did not meet discharge criteria for the projected LOS, the LOS could be extended. Reasons for not achieving the LOS target were coded and recorded during team rounds, and were based on discharge criteria. A revised discharge date was then set and recorded. This information will be used to identify discharge barriers and inform future program planning.

Development of decision support tools for discharge

The determination that an individual is ready for discharge is a key driver of LOS. Often this involves informal decision making based on clinical judgment and experience. In addition, there is a need to build consensus among team members. In this context, it is not surprising that significant variability can occur due to individual clinicians and the makeup of the team. In our institution, this issue is compounded by the fact that care is provided on three distinct units.

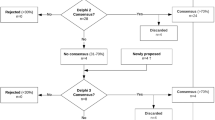

In order to address these issues, program clinicians were engaged to identify the specific requirements needed to safely and responsibly discharge a client to the community. The following criteria were identified: (1) the individual no longer requires overnight nursing, (2) there is a safe (defined by the team) and appropriate environment in which to live, (3) required equipment has been provided, (4) the individual (or caregiver) has the physical and/or verbal ability to direct or manage care and (5) function can be maintained or improved further in the community. Discharge determinants were then incorporated into a decision tree (Figure 2). The discharge decision tree was then implemented as a reference tool to guide discussions at weekly team conferences and ensure consistency in discharge decision making. Clients could be discharged before the tentative discharge date if they met the defined discharge criteria.

For ease of use, the determination of tentative discharge dates was automated using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). This became known as the Tentative Discharge Date Calculator. A patient census tool provided additional support and guidance during weekly team rounds. The report provided the tentative discharge date for each patient. A reference key was also incorporated to facilitate the coding and recording of contributing factors when discharge criteria were not met and individual patients did not meet their accompanying tentative discharge dates.

Communication and implementation

A structured communication strategy was devised. Before implementation, proposed changes were presented to program clinicians using multiple forums – program wide town hall, weekly interdisciplinary team meetings, nursing meetings and physician meetings. The benchmarking exercise revealed that program LOS lagged national comparators for individuals undergoing initial inpatient rehabilitation. The results were used to frame the issue and reinforce the need and importance of the initiative.

Program representatives also met or initiated communication with important external stakeholders such as acute care facilities and community partners. Feedback and concerns were solicited and addressed. Following initial implementation, metrics were measured on an ongoing basis and feedback on performance provided to clinical teams at regular intervals.

Evaluation

Outcome measures were average LOS, FIM change and FIM efficiency. FIM change is defined as discharge FIM score minus admission FIM score. FIM efficiency is FIM change divided by LOS. The FIM is an established, reliable and validated measure of function following SCI.10, 11 Although a newer measure, the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM), has some psychometric advantages this does not render the FIM invalid10, 11 and the FIM is still widely used. A decision was therefore made to capture the FIM as reporting of this measure is required and it would facilitate external benchmarking. Client satisfaction was also monitored for changes post-implementation. The hospital had a long-standing process for measuring client satisfaction using mailed questionnaires post-hospital discharge.

Results

The initiative was implemented at the beginning of March 2010. Outcomes are reported for patients admitted for initial inpatient rehabilitation for the 2010/11 fiscal year extending from April 1, 2010 to March 31, 2011, and compared with prior fiscal years. Fiscal years for the organization extend from April 1 through March 31 inclusive.

Patient cohort

Two hundred twenty five patients were admitted for initial inpatient rehabilitation during 2010/11. Two hundred and twenty one individuals were discharged from initial inpatient rehabilitation during the 2010/11, and had reportable data available from NRS. Patient demographics for 2010/11 are summarized in Table 1. Consistent with provincial and national trends, there was a trend towards increasing age. Mean age for 2010/11 was 54.6 years and 61% male; compared with 48.5 years and 69% male (n=190; 2008/09) and 54.1 years and 68% male (n=197; 2009/10) for prior years.

Patients were categorized as neurological, traumatic or non-traumatic, which aligned with the RPG classification. Categories for 2010/11 were 5% neurological, 39% traumatic and 56% non-traumatic. Corresponding information for prior years was as follows – 6% neurological, 48% traumatic, 46% non-traumatic (2008/09) and 6% neurological, 38% traumatic, 56% non-traumatic (2009/10). Chi-square testing did not reveal significant differences between 2010/11 and 2009/10. There were more cases of non-traumatic SCI in 2010/11 compared with 2008/09 (P-value=0.0071).

The RPG classification categorizes patients according to injury etiology, severity of functional impairments and age (Figure 1). Chi-square testing did not reveal significant differences between 2010/11 and 2009/10, however, there were significant differences between 2010/11 and 2008/09 (P-value=0.0001). In 2010/11, more patients presented in the RPGs with lower admission motor FIM scores.

LOS, FIM change and efficiency

Mean LOS was 71.5 days for 2010/11 (Figure 3); a 14 and 17% reduction compared with 2008/09 (83.4 days) and 2009/10 (86.2 days) respectively. FIM change and FIM efficiency were 33.2 and 0.54 for 2010/11. Although LOS decreased for 2010/11, FIM change and FIM efficiency increased 9 and 54% compared with 2008/09 and 16 and 32% compared with 2009/10 (Figures 4 and 5). Patient satisfaction scores remained stable or improved during implementation, including the specific domains of (1) coordination of care and (2) continuity and transition.

Discussion

Health care costs are escalating worldwide and there is a growing need to provide health care in the most efficient manner possible without compromising outcomes. SCI rehabilitation in particular is expensive and resource intensive. Although LOS has been decreasing in many settings,12, 13 there is still considerable variability globally.7, 12, 13, 14, 15 Despite the importance of this issue, there has been little published regarding approaches to improving the efficiency of inpatient rehabilitation for SCI.

One approach to improving outcomes is to introduce more efficacious therapeutic interventions; the typical emphasis of clinicians. Alternatively patient outcomes and system efficiency can be improved through the evaluation and improvement of the processes involved in care delivery. This is true of any complex organization and the provision of inpatient rehabilitation is a complex endeavor involving many processes and many individuals typically working as an interdisciplinary team.

Using benchmarking, process standardization and the development and implementation of decision support tools, the authors were able to decrease LOS, while simultaneously improving FIM change and efficiency. Benefits included better patient outcomes, lower costs, the provision of care to more clients per annum and improved patient flow across the health care continuum (acute care→rehabilitation→community).

Benchmarking is a sharing of performance data among entities in the same industry or professional area. Performance data can be used to set new, objective benchmarks for future performance. Benchmarking is routine in many industries and has been previously used and associated with improved outcomes in rehabilitation settings.4, 16, 17, 18, 19 Benchmarking is useful for setting organizational goals and increasing performance expectations. Incentives can also be used to increase performance expectations. The implementation of a prospective payment system for Medicare patients (USA) provided a fiscal incentive for shortening LOS. LOS for medicare patients with SCI subsequently decreased, while functional outcomes were maintained.9

Process standardization was also employed, primarily through the development of a methodology for determining anticipated LOS based on initial presentation. Standardization ensures that the desired approach consistently occurs and is particularly important in large organizations where there is the potential for substantial variability. Standardization had the additional benefit of enhancing transparency from the perspective of both clients and staff. This had been a commonly expressed concern in the program.

Standardization can be particularly difficult when a process involves many individuals and requires judgment and active decision-making. Decision supports (for example, decision trees, defined criteria) can be extremely valuable in the rehabilitation setting when consistency in approach is desired.20 Decision supports have successfully guided discharge decision making and the provision of rehabilitation services such as peri-operative physical therapy.21 Although standardization is important, the process must accommodate modifications when appropriate. In this case, the projected LOS provided an objective target, but was not rigidly enforced and could be adjusted if the patient did not achieve the defined discharge criteria. In this initiative, the tentative discharge date facilitated earlier team discussions related to discharge planning and barriers. The implementation of tools to support standardization and decision making has also facilitated data collection regarding observed barriers to discharge, which will inform future program planning.

Limitations

The initiative was not a research trial, but a performance improvement initiative. As such, there was not the opportunity to determine participants and study cohorts using methodologies such as inclusion/exclusion criteria, stratification and randomization. As a result, there was some year to year variation in the observed patient population despite the fact that the program is the only one of its kind within its catchment area and has very stable referral patterns. There was a trend towards increasing age. In 2008/09, the percentage of traumatic SCI was higher and presenting functional impairments were less severe. Despite the fact that older age and greater functional impairments (2010/11 compared with 2008/09) would be expected to negatively impact outcome measures, FIM change, FIM efficiency and LOS all improved.

Reportable data (demographics and results) was also largely determined by available hospital metrics and information requests from the NRS. Results should therefore be evaluated in the context of clinical performance improvement, rather than a clinical trial. Despite these limitations, practical approaches are outlined, which can be generalized and implemented in other clinical settings.

Challenges and next steps

A significant challenge was achieving staff buy-in and engagement. Ongoing communication was essential. Information was presented in multiple formats and forums; providing staff with the opportunity to provide feedback and raise concerns. Structured feedback on performance and evaluation metrics was provided regularly. The ability to show tangible and objective change was invaluable for obtaining ongoing buy-in and the support of internal and external stakeholders.

Much of the required data collection and analysis required manual data entry, compilation and computation. The efficiency and accuracy of future data collection will need to be refined and automated as much as possible, by linking databases in combination with the automated population of required data fields and accompanying generation of reports.

Sustainability will require ongoing monitoring, data collection and targeted adjustments based on new information. This includes periodically revisiting and adjusting LOS targets. The program is also impacted by the social context in which it operates. Discharge barriers (for example, housing and equipment availability) will need to be addressed in order to achieve further reductions in LOS. Data on discharge barriers will aid future decision making, and inform advocacy efforts to the Ministry of Health as well as other important external decision- and policy-makers.

Conclusion

Despite the challenges, resources and costs associated with spinal cord rehabilitation, there is little published on approaches to maximizing process efficiency. This will become increasingly important as health care costs increase and resources contract. A large inpatient program was able to improve program efficiency and reduce LOS while simultaneously improving patient outcomes. This was achieved through a performance improvement initiative which employed benchmarking, process standardization and the development and implementation of decision support tools. Additional studies are needed that define and optimize the processes involved in the provision of rehabilitation to individuals with SCI.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Cao Y, Chen Y, DeVivo MJ . Lifetime costs after spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Rehabil 2011; 16: 10–16.

DeVivo MJ, Chen Y, Mennemeyer ST, Deutsch A . Costs of care following spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Rehabil 2011; 16: 1–9.

Bradley LJ, Kirker SGB, Corteen E, Seeley HM, Pickard JD, Hutchinson PJ . Inappropriate acute neurosurgical bed occupancy and short falls in rehabilitation: implications for the National Service Framework. Br J Neurosurg 2006; 20: 36–39.

Meyer M, Britt E, McHale HA, Teasell R . Length of stay benchmarks for inpatient rehabilitation after stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2012; 34: 1077–1081.

Lowthian P, Disler P, Ma S, Eager K, Green J, de Graaf S . The Australian National Sub-acute and Non-acute Patient Classification (AN-SNAP): its application and value in a stroke rehabilitation programme. Clin Rehabil 2000; 14: 532–537.

McKenna K, Tooth L, Strong J, Ottenbacher K, Connell J, Cleary M . Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 81: 47–56.

Tooth L, McKenna K, Geraghty T . Rehabilitation outcomes in traumatic spinal cord injury in Australia: functional status, length of stay, and discharge setting. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 220–230.

Tooth L, McKenna K, Goh K, Varghese P . Length of stay, discharge destination, and functional improvement: utility of the Australian National Subacute and Nonacute Patient Casemix Classification. Stroke 2005; 36: 1519–1525.

Qu H, Shewchuk RM, Chen Y, Deutsch A . Impact of medicare prospective payment system on acute rehabilitation outcomes of patients with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92: 346–351.

Anderson K, Aito S, Atkins M, Biering-Sorenson F, Charlifue S, Curt A et al. Functional recovery measures for spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 133–144.

Alexander MS, Anderson KD, Biering-Sorenson F, Blight AR, Brannon R, Bryce TN et al. Outcome measures in spinal cord injury: recent assessments and recommendations for future directions. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 582–591.

Ronen J, Itzkovich M, Bluvshtein V, Thaleisnik M, Goldin D, Gelernter I et al. Length of stay in hospital following spinal cord lesions in Israel. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 353–358.

DeVivo MJ . Trends in spinal cord injury rehabilitation outcomes from model systems in the United States: 1973-2006. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 713–721.

Post MW, Dallmeijer AJ, Angenot EL, van Asbeck FW, van der Woude LH . Duration and functional outcome of spinal cord injury rehabilitation in the Netherlands. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005; 42: 75–85.

Osterthun R, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA . Characteristics, length of stay and functional outcome of patients with spinal cord injury in Dutch and Flemish rehabilitation centres. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 339–344.

Compton J, Robinson M, O’Hara C . Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health. Benchmarking critical pathways—a method for achieving best practice. Aust Health Rev 1995; 18: 101–112.

Anonymous Rehab facility overcomes scarcity of models to make benchmarking pay. Healthcare Benchmarks 1997; 4: 25–27.

Kunio R . Benchmarking rehab for better care, more reimbursement. Nurs Homes Long Term Care Manage 2007; 56: 16–20.

Simmonds F . Benchmarking outcomes in rehabilitation—the Australasian Rehabilitation Outcomes Centre story. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1647.

Goud R, de Keizer NF, ter Riet G, Wyatt JC, Hasman A, Hellemans IM et al. Effect of guideline based computerized decision support on decision making of multidisciplinary teams: cluster randomized trial in cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2009; 338: b1440.

Brooks D, Parsons J, Newton J, Dear C, Silaj E, Sinclair L et al. Discharge criteria from perioperative physical therapy. Chest 2002; 121: 488–494.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff of the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Brain and Spinal Cord Rehabilitation Program for their participation and support during implementation of the performance improvement initiative. The FIM instrument, data set and impairment codes referenced herein are the property of Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, a division of University at Buffalo (UB) Foundation Activities, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, A., Yee, J., Flett, H. et al. Impact of benchmarking and clinical decision making tools on rehabilitation length of stay following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 51, 165–169 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.91

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.91

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinician based decision tool to guide recommended interval between colonoscopies: development and evaluation pilot study

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making (2022)

-

A comparative examination of models of service delivery intended to support community integration in the immediate period following inpatient rehabilitation for spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

Spinal Cord Essentials: the development of an individualized, handout-based patient and family education initiative for people with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2014)

-

Effect of rehabilitation length of stay on outcomes in individuals with traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury: a systematic review protocol

Systematic Reviews (2013)