Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the characteristics of neuropathic pain and observe intensity alterations in pain with regard to time during the day in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients.

Methods:

A total of 50 SCI patients (M/F, 40/10; mean age, 35±12 years) with at-level and below-level neuropathic pain were included in the study. All patients were examined and classified according to the ASIA/ISCoS 2002 International Neurologic Examination and Classification Standards. The history, duration, localization and characteristics of the pain were recorded. Neuropathic pain of patients was evaluated with the McGill-Melzack Pain Questionnaire and LANSS (Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs) Pain Scale. Visual analog scale (VAS) was used to measure the severity of pain four times during the day. Quality of life was analyzed with Short Form 36.

Results:

Out of 50 patients, 10 were tetraplegic and 40 were paraplegic. In all, 28 patients had motor and sensory complete injuries (AIS A), whereas 22 patients had sensory incomplete (AIS B, C and D) injuries. The most frequently used words to describe neuropathic pain were throbbing, tiring, hot and tingling. Pain intensity was significantly higher in the night than in the evening, noon and morning (P<0.05) (VAS morning: 5.16±2.42, VAS noon: 5.24±2.52, VAS evening: 5.80±2.46 and VAS night: 6.38±2.19).

Conclusion:

Neuropathic pain is a serious complaint in SCI patients and affects their quality of life. Neuropathic pain intensity was higher in the night hours than other times of day. This situation reinforces the need for a continued research and education on neuropathic pain in SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic pain is found to be quite common in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients, with a prevalence ranging from 11 to 94%. Approximately 30% of chronic pain manifests as neuropathic pain.1, 2, 3 The SCI Pain Task Force of the IASP broadly classifies SCI pain into nociceptive and neuropathic pain.4, 5

Neuropathic pain can be defined as abnormal pain sensation in peripheral or central nervous system following injuries.6 It is caused by dysfunctions in the peripheral or central nervous system without peripheral nociceptive stimulation.6, 7 Neuropathic pain syndromes represent a group of highly heterogeneous clinical conditions.1, 8

Pain is also reported to be one of the factors that interfere with quality of life of patients with SCI.5, 9, 10 Pain directly contributes to disability by reducing the person’s capacity to participate in rehabilitation.11

There are many studies on chronic pain after SCI. However, in the investigation of the pain following SCI, careful attention needs to be paid in order to identify specific pain types.8 The present study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics of neuropathic pain in SCI patients, courses of severity of neuropathic pain in a day and the relationship between neuropathic pain and quality of life of SCI patients.

Materials and methods

A total of 50 SCI patients (M/F, 40/10; mean age, 35±12 years) with neuropathic pain at level or below level of injury were included in this study. The patients who participated in the study had to be 18 years or older. Neuropathic pain was diagnosed by examination of an experienced physiatrist and confirmed with a LANSS (Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs) score of 12 and above. The patients suffering from pain other than neuropathic pain were excluded to avoid interferences of other pain types. Therefore, patients with urinary infections, heterotrophic ossification formation, pressure ulcer and severe spasticity (Ashworth 3 or more), who may have severe pains that may alter severity and characteristics of neuropathic pain, were also excluded. All patients were examined and classified according to the ASIA/ISCoS 2002 International Neurologic Examination and Classification Standards. We have also recorded the characteristics of patient demographics.

Neuropathic pain assessments were carried out by using the LANSS Pain Scale and Mc-Gill Melzack pain questionnaire. The history, duration, localization and characteristics of pain were recorded. Visual analog scale (VAS) was used to identify the severity of pain four times (morning, noon, evening and night) during the day. We studied quality of life with Short Form 36. All questionnaire forms were filled by patients in the hospital.

Statistical analysis

In addition to descriptive statistics, the Wilcoxon test and Spearman correlation tests were used to compare the results in the group. P⩽0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We certified that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were adhered to during the course of this research.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristic of patients together with pain assessments are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Of the SCI patients, 70% (35/50) reported that neuropathic pain had begun during the first 6 months of injury. Average pain duration was 25.80±47.68 months (range, 1–282 months) (Table 3).

Patients felt neuropathic pain mostly in the legs. In all, 40 SCI patients felt neuropathic pain inside the body (internally), 7 patients felt neuropathic pain on the surface of the body (externally) and 3 patients felt neuropathic pain both internally and externally (Table 3).

Patients reported that pain-aggravating factors were resting, physical activity, cold, anxiety, sleeplessness and heat, whereas pain-alleviating factors were medicine, physical activity, rest, heat and cold. A total of 23 patients reported that nothing alleviated pain, whereas 21 patients reported that nothing aggravated the pain (Table 4).

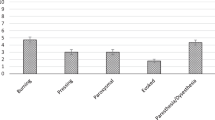

The mean VAS score was 5.16±2.42 in the morning, 5.24±2.52 in the noon, 5.80±2.46 in the evening and 6.38±2.19 in the night. The mean of the night VAS scores was statistically higher than the VAS scores of the morning (P<0.05) and VAS scores of the noon (P<0.05) (Table 5; Figure 1). The mean VAS score for the female patients was 5.30±2.45 in the morning, 5.20±2.49 in the noon, 7.20±1.99 in the evening and 6.90±2.96 in the night. In addition, the mean VAS score for male patients was 5.12±2.44 in the morning, 5.25±2.56 in the noon, 5.45±2.47 in the evening and 6.62±1.98 in the night. When we compared female versus male VAS scores in the morning, noon, evening and night, the pain intensity was statistically higher in female patients than in male patients, only in terms of the evening VAS scores (P<0.05) (Table 6; Figure 2).

The mean LANSS score was 15.83±2.36 and range was 13–23. There was no correlation between VAS scores and LANSS scores. The most common descriptors used by patients to describe their neuropathic pain were throbbing, tiring, hot and tingling (Table 7).

When we compared the relationship between neuropathic pain and quality of life using Short Form 36, we observed a correlation between emotional role and morning, noon, evening and night VAS scores. Correlation also existed between physical role and morning VAS score. Finally, total Short Form 36 score was correlated with noon and evening VAS score (Table 8).

Discussion

This study focused particularly on the properties of neuropathic pain after SCI. This is the first study in the literature monitoring daily courses of neuropathic pain intensity in SCI. We found that only evening VAS scores of female patients were statistically more intense than evening VAS scores of male patients. Morning, noon and night VAS scores were not statistically different between male and female patients. In addition, we found that neuropathic pain intensity was statically significantly higher at night than in the morning and noon. Neuropathic pain was mostly seen in patients aged between 30 and 39 years, but there was no correlation between daily course of neuropathic pain severity and age in our research.

There are many studies about factors that affect neuropathic pain, and various results have been observed. Budh et al.3 reported that no gender differences could be detected in neuropathic pain in terms of its onset, distribution, location, influencing factors and its severity. In addition, Finnerup et al.4 reported that there was no statistical difference in pain severity between gender groups, as it was in Werhagen research.9 Werhagen et al.9 did not find any statistically significant difference between neuropathic pain prevalence with regard to complete versus incomplete injury and tetraplegia versus paraplegia. In addition, in studies by Ravenscroft12 and Ullrich13, completeness of injury and level of injury were not significantly related to chronic pain intensity. However, these two studies were about chronic pain, not specifically about neuropathic pain. On the other hand, Siddall et al.14 found that neuropathic pain was more common among patients with tetraplegia rather than paraplegia. Werhagen et al.9 suggested that the prevalence of neuropathic pain increased with the third, fifth and higher decades of life. Ravenscroft et al.12 presented that the presence of chronic pain did not correlate with differences in age. Ullrich et al.13 suggested that age at SCI and time since SCI were also not significantly related to pain intensity or interference. These two studies were about various types of pain, not only neuropathic pain.

In some studies, the researchers found that the neuropathic pain had begun mostly within the first 6 months after SCI, whereas in other resources it was reported that it had begun mostly within the first year of SCI. Budh et al.3 reported that most SCI patients experienced pain within 3 months after SCI. In the study by Henwood and Ellis15 the majority of SCI patients reported that neuropathic pain appeared within the first 6 months of injury. Ravenscroft et al.12 reported that in 63% of patients chronic pain had begun within the first 6 months of injury. Siddall et al.14 suggested that the mean of onset of at-level neuropathic pain was 1.2 years and the mean of onset of below-level neuropathic pain was 1.8 years. Störmer et al.16 reported that the onset of pain/dysesthesiae was within the first year, in 58% of SCI patients, and that the patients even declared that pain/dysesthesiae had begun immediately after they suffered from SCI, in 34%of cases. Our study revealed that 70% of neuropathic pain began within the first 6 months of injury, as it was in the review of Miguel and Kraychete.17

Siddall et al.14 reported that SCI patients with neuropathic pain at or below the level of the injury, 60% and 48%, respectively; described pain as severe or excruciating. Demirel et al.18 reported that pain (all type of pain) was more intense in the evening. Also in our research, neuropathic pain intensity was statically significantly higher at night than in the morning and noon. This result is important for dealing with neuropathic pain.

Finnerup et al.4 reported that stress, anxiety, tiredness, weather changes and cold were pain (and dysesthesia)-aggravating factors, whereas rest, physical activity and alcohol were pain (and dysesthesia)-alleviating factors. In another study, respondents identified muscle spasm, activity, touching the painful area, getting worked up and cold weather as exacerbating factors but massage, the application of heat and drugs as alleviating factors. However, these factors were not only affecting neuropathic pain but other types of pain as well.12 In our study, many patients reported that nothing changed pain severity. Only 18% of the patients reported that medicine could lessen neuropathic pain. Also 16% of patients reported that rest could aggravate the pain.

The use of verbal expressions by individuals to define their pain state is clearly a common phenomenon. Indeed, verbal descriptors are common criteria used by most classification schemes to categorize pain following SCI.19 Putzke et al.19 reported 29 SCI patients with all pain types. Tingling and sickening tend to be associated with neuropathic pain.19 Finnerup et al.,4 in their post-survey study, reported that the most frequent words used to describe pain and dysesthesiae at or below lesion level were pricking, tingling, shooting, tiring, taut, annoying and burning. Störmer et al.16 reported that for describing pain/dysesthesiae SCI patients used the following words: burning, tingling, stabbing and tight, tense feeling. Neuropathic pain descriptors such as ‘a sharp hot dagger’, sharp needle, stabbing, hacksaw, burning, searing, frozen, pressure-wise and hit by a hammer were used in a research.15 In our study, the McGill Pain Questionnaire was completed specifically for identifying neuropathic pain that was located at or below level of injury. Throbbing, tiring, hot, tingling, stinging were the most commonly used adjectives by patients to describe neuropathic pain.

Pain is one of the most important factors that interfere with daily-life activities after SCI.1, 9, 10 Werhagen et al.9 suggested that 70% of SCI patients with pain declared that pain affected their life to a great extent. In addition, another study reported that the pain associated with SCI was a major cause of distress. Finnerup et al.4 reported that 27% of patients reporting pain and dysesthesia rated it as severe, and more than 90% described it as interfering with daily life. Ravenscroft et al.12 suggested that 50% of patients with pain considered pain as their worst medical problem and as being a major cause of unemployment and depression. SCI patients demonstrated that chronic pain had a negative impact on their quality of life. In a study by Störmer et al.,16 23% of SCI patients with pain/dysesthesiae reported that their daily life was affected and limited by pain and another 23% reported that their symptoms did not affect their daily life. Rintala et al.20 reported that 51.9% male SCI patients were affected by chronic pain, and that 21.1% of patients with pain needed to stop working because of pain. In our study, neuropathic pain affects emotional role during all four periods (morning, noon, night, evening), but only pain in the morning affected physical role.

Conclusions

The literature review unveils the large number of publications that focused on the pain in SCI patients. To our knowledge, there are few specific data on neuropathic pain for this population. This research focused only on the neuropathic pain after SCI with a survey study. Finally, it was the first study that evaluated intraday intensity variation of neuropathic pain.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Calmels P, Mick G, Perrouin-Verde B, Ventura M . Neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury: identification, classification, evaluation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2009; 52: 83–102.

To TP, Lim TC, Hill ST, Frauman AG, Cooper N, Kirsa SW et al. Gabapentin for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 282–285.

Budh NC, Lund I, Hultling C, Levi R, Werhagen L, Ertzgaard P et al. Gender related differences in pain in spinal cord injured individuals. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 122–128.

Finnerup NB, Johannesen IL, Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Jensen TS . Pain and dysesthesia in patients with spinal cord injury: a postal survey. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 256–262.

Siddall PJ . Management of neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: now and in the future. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 352–359.

Ro LS, Chang KH . Neuropathic pain: mechanism and treatments. Chang Gung Med J 2005; 28: 594–604.

Widerström-Noga EG, Turk DC . Types and effectiveness of treatments used by people with chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: influences of pain and psychosocial characteristics. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 600–609.

Yucel A, Senocak M, Orhan EK, Cimen A, Ertas E . Results of the leeds assesment of neuropathic symptoms and signs pain scale in Turkey: a validation study. J Pain 2004; 5: 427–432.

Werhagen L, Budh CN, Hultling C, Molander C . Neuropathic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury- relations to gender, spinal level, completeness, and age at the time of injury. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 665–673.

Perry KN, Nicholas MK, Middleton J . Spinal cord injury-related pain in rehabilitation: a cross-section study of relationships with cognitions, mood and physical function. Eur J Pain 2009; 13: 511–517.

Sang-Ho A, Hea-Woon P, Burn-Suk L, Hac-Won M, Sung-Ho J, Joon S et al. Gabapentin effect on neuropathic pain compared among patients with spinal cord injury and different durations of symptoms. Spine 2003; 28: 341–346.

Ravenscroft A, Ahmed YS . Chronic pain after SCI. A patient survey. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 611–614.

Ullrich PM, Jensen MP, Loeser JD, Cardenas DD . Pain intensity, pain interferences and characteristics of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 451–455.

Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ . A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003; 103: 249–257.

Henwood P, Ellis JA . Chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury: the patient’s perspective. Pain Res Manage 2004; 9: 39–45.

Störmer S, Gerner HJ, Grüninger W, Metzmacher K, Föllinger S, Ch Wienke et al. Chronic pain/dysaesthesiae in spinal cord injury patients: results of a multicentre study. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 446–455.

Miguel MD, Kraychete DC . Pain in patients with spinal cord injury: a review. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2009; 59: 350–357.

Demirel G, Yilmaz H, Gencosmanoglu B, Kesiktas N . Pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 25–28.

Putzke JD, Richards JS, Hicken BL, Ness TJ, Kezar L, DeVivo M . Pain classification following spinal cord injury: the utility of verbal descriptors. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 118–127.

Rintala DH, Loubser PG, Castro J, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ . Chronic pain in a community-based sample of men with spinal cord injury: prevalence, severity, and relationship with impairment, disability, handicap, and subjective well-being. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 604–614.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Celik, E., Erhan, B. & Lakse, E. The clinical characteristics of neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 50, 585–589 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.26

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.26

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pilot study of feasibility and effect of anodal transcutaneous spinal direct current stimulation on chronic neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

An examination of diurnal variations in neuropathic pain and affect, on exercise and non-exercise days, in adults with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2018)

-

Neuropathic pain in a rehabilitation setting after spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of inpatients’ experiences

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2017)

-

Translation of the rat thoracic contusion model; part 1—supraspinally versus spinally mediated pain-like responses and spasticity

Spinal Cord (2014)

-

The effect of low-frequency TENS in the treatment of neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2013)