Abstract

Study design:

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives:

To examine predictors of oral health in people with spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods:

Ninety-two people with SCI (⩾6 months, 44% cervical level) completed questionnaires and underwent oral examination. Socio-economic, injury-related and oral habits variables were used for predicting Oral Health Score (OHS); Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) score; and Periodontal Screen and Recording Index (PSR).

Results:

Most people with SCI were able to bring at least one hand to the mouth (82%) and brush teeth independently (65%). Regarding daily oral habits, 84% reported brushing teeth, 48% rinsing mouth, 14% flossing, 33% tobacco use and 13% mouthstick use. Only 32% had teeth cleaned within the past year. Oral examination revealed three decayed and eight missing teeth on average, with prominent periodontal disease (64%). Employment before SCI and more risky oral habits were significant predictors of worse OHS (P=0.005 and P=0.014, respectively) and PSR score (P=0.010 and P=0.035, respectively). Older age was the only predictor of worse DMFT score (P<0.001).

Conclusion:

Oral health appears compromised in people with SCI. Identification of modifiable risk factors warrants examination whether intervention with focus on behavioral changes may improve oral health in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prevention of secondary complications and promotion of a healthy lifestyle are the major goals for the aging population of people with spinal cord injury (SCI). The emphasis has been put on prevention of diseases common in the general population (diabetes, cardiovascular disease) in addition to those specific to SCI (respiratory, urinary, skin, bone). However, comparably little is known about the oral health in people with SCI. This seems relevant because of a strong link between oral health and overall health,1 as also indicated by association between dental hygiene, markers of systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease.2, 3, 4

Several risk factors for poor oral health in the general population may also pertain to people with SCI. With advanced age more dental problems arise.5 Oral hygiene and frequency of dental visits tends to be worse in men than women.6 Oral hygiene differs among certain races and ethnic groups,7 with African-Americans reporting higher rates of unmet needs for oral health care.8 Low socio-economic status is associated with tooth loss9 and tooth decay.10 Thus, the typical demographic and socio-economic profile of people who sustained SCI puts the majority at an increased risk for developing oral and dental problems.

Additional factors unique to the SCI population may heighten their risk for developing oral diseases. Tobacco use, specifically smoking, is common in people with SCI.11 Smoking impedes the ability to heal soft tissue and bone, which, in combination with an increased number of periodontal pathogens found in smokers, can contribute to periodontal disease.12, 13, 14 Also, smokeless tobacco use results in recession of the gums and tooth root exposure causing periodontal breakdown and risk for decay.14 Upper limb weakness, impaired mobility and environmental barriers limit the ability of people with SCI to carry out proper oral hygiene on their own15 or make regular dental visits,16 which was found associated with worse oral health in the general population.17, 18 Use of a mouthstick for driving and controlling devices may contribute to occlusal and oral tissue trauma19 and promote the growth of bacteria. Altered mood and depressive symptoms are prevalent in people with SCI,20 and depressed individuals are at higher risk for developing periodontitis21 and have worse dental health.22 Besides anti-depressants,23 widespread use of anti-cholinergic agents in people with SCI can cause a decrease in salivary flow,24 leading to an increased rate of decay, periodontal disease and oral infection.25

Despite converging evidence of a potentially increased risk for developing oral and dental problems in people with SCI, the literature on this topic is scarce. In a study that recruited 16 people with tetraplegia sustained >8 years earlier, Stiefel et al.26 reported that those who were dependent tended to have more plaque and gingivitis than those brushing independently. In a separate study, moderate-to-poor oral hygiene and increased plaque and gingivitis were also found in most of the 12 people with tetraplegia examined within 2 years of SCI.27 Based on a mailed survey, Yuen et al.28 concluded that people with SCI were less likely to have annual dental cleaning, and identified physical barriers and fear of dentists as two factors associated with less frequent visits. Sullivan29 recently reported that people with SCI are largely unaware of their dental problems.

The objective of this study was to broaden knowledge about the status and predictors of oral health in people with SCI. The specific aims were (1) to determine oral health status in a larger and diverse sample of people with SCI and (2) to identify which non-modifiable and modifiable factors are significant predictors of oral health in the same population. Factors considered during the development of conceptual model for this study included demographic and socio-economic characteristics, behavioral factors (oral hygiene, nutrition, tobacco use), motor impairments (arm function), psychological well-being (adjustment, mood, support network), general physical health (pressure sores, urinary infections), co-morbidities (oral disease, diabetes), mediation use (anti-cholinergic drugs) and access to care (insurance, barriers). Considering previous findings in the general population and specifics of SCI, we hypothesized that the significant predictors of oral health may be found among advanced age, African-American ethnicity, less favorable socio-economic status, higher SCI, more severe upper limb involvement, frequency of urinary tract infections and greater number of oral habits constituting a risk for oral health. The results may guide future research toward development and evaluation of treatment and prevention programs specifically tailored to the SCI population.

Materials and methods

The study participants were recruited among the SCI population who received care at Methodist Rehabilitation Center, the major provider of comprehensive rehabilitation for SCI in Mississippi. The subjects screened for the study were the current inpatients, those scheduled for out-patient visits, and residents of Methodist’s Specialty Care Center, a long-term residential facility for severely impaired individuals. The inclusion criteria were (1) SCI sustained at least 6 months before enrollment; (2) ability to communicate and cooperate with a dental examination; and (3) signed consent form by the participant or proxy. The exclusion criteria were (1) joint replacement within 2 years; (2) history of infectious endocarditis; (3) surgical repair of congenital heart defect; and (4) artificial heart valve implant, as a precaution to avoid potential spread of bacteria after placing a periodontal probe below gingiva. Eligible subjects were approached in a private room by the lead study investigator who described the study, obtained the consent, administered surveys, and performed a dental examination. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research of the involved institutions.

Survey instrument

The survey was developed through a consensus of a dentist, dental hygienist, rehabilitation researcher, rehabilitation nurse, occupational therapist and a statistician. The survey inquired about socio-demographic status, SCI-related status and dental status.

The socio-demographic variables were age, race, county of residence and socio-economic status (education level, current and past vocational status and household income). The SCI-related variables were date and level of injury, living situation, functional mobility, community mobility, health status including history of pressure sores and urinary tract infections, current medications and satisfaction with life.30 The upper limb capacity was evaluated based on self-perceived ability to bring at least one hand to mouth and oral hygiene independence measure. The latter referred to a teeth brushing task and used a grading scheme of the functional independence measure. Additional questions included the use of tobacco products and the use of a mouthstick for controlling devices. Finally, the survey inquired about daily brushing, flossing and use of mouth rinse, and time since last professional teeth cleaning.

Assessment of oral health

Oral health was assessed with three commonly used dental scales. The Oral Health Score (OHS) was selected because it is easily administered and provides patient perception of oral health that is considered valid.31 The OHS asks eight questions about comfort in the mouth and the perception of caries (decay), dental wear, periodontal (gum and bone) disease, occlusion, mucosa and dentures, if applicable. The questions are variably scored from 0 up to 20 for a total OHS score from 0–100. A score of >90 indicates ‘good oral health,’ 80–90 ‘not that bad oral health,’ 70–80 ‘treatment is needed’ and <70 ‘immediate care is necessary.’

The Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) score is based on evaluation by a dental professional and has been widely used in surveys as a simple means of evaluating dental status.32 The scoring is based on 32 teeth and the status of each tooth is noted (D, M or F). The total DMFT score represents the aggregate number of decayed (D), missing (M) and filled (F) teeth.33 In addition to the total DMFT score, we also analyzed the D score and F score separately because present or past decay indicates the need for treatment.

Periodontal disease was measured by the American Dental Association’s Periodontal Screen and Recording Index (PSR). This ordinal scale evaluates the presence of supragingival calculus (tarter build up above the gums), subgingival calculus (tarter build up below the gums), pocket depths of 4–5 mm, pocket depths of 6 mm and more, gingival bleeding after probing, gum recession (loss of gums), abscess and edentulism (loss of teeth).34 Each of the six sections (sextants) of the oral cavity is assigned a score of 0 for healthy gums; 1 for bleeding; 2 for calculus/tarter; 3 for shallow gingival pockets; 4 for deep periodontal pockets; 5 for recession, mobility or mucogingival involvement; and 6 for complete absence of teeth. The highest (worst) score among all sextants is taken as the PSR Index.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Carry, NC, USA) were used for statistical analysis. The sample size was determined assuming the power of 0.8, α level of 0.05, R2 of 0.2, and an entry of 14 independent variables in the prediction model, which required a minimum sample of 88. The actual number of participants enrolled was 92. In preliminary analysis, however, the number of predictor variables was reduced making the sample size of 92 more than adequate.35

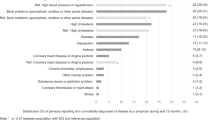

For descriptive purposes, frequency distribution and mean±s.d. were calculated. Univariate analyses were first conducted to test for co-linearity among the predictor variables. Based on these results and after eliminating variables with missing responses (for example, income 25%), the number of predictor variables entered in the final analysis was reduced from 14 to 9. The independent variables included in each predictive model were age, gender, ethnicity, vocational status, level of SCI, upper extremity function, life satisfaction, number of risky oral habits (not flossing, no professional teeth cleaning in the past year, daily tobacco use, daily mouthstick use) and frequency of urinary tract infections requiring antibiotics as a proxy of general health. For OHS (continuous variable), ordinary least-square linear regression was used on the raw scores. For DMFT (count variable), Poisson regression was first considered but later replaced by the negative binomial regression because the latter provided better goodness of fit (χ2 test non-significant, P=0.173) and the risk ratios were reported. For PSR (ordinal variable), ordered logistic multinominal regression was performed on raw scores and the odds ratios were reported.

Results

Sample characteristics

The demographic characteristics of 92 SCI persons included in the study are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 41 years and the mean age at injury was 33 years. The majority were men (72%), Caucasians (55%), with high-school diploma (57%), currently unemployed (75%) but previously employed (74%), and with an annual income of <$15 000 (35%). The majority (65%) lived with another person who helped with care. About the same percentage lived in designated rural and urban areas of the state.36

SCI affected the cervical region in 44, thoracic in 41 and lumbar in 10 (Table 2). The majority (83%) used a wheelchair for mobility and 38% could drive a car. The mean score on the satisfaction with life scale was 2.8 out of a possible 5, with 39% reporting dissatisfaction with the statement ‘I am satisfied with my life.’ The majority (70%) reported no health problems unrelated to SCI. Nearly 80% had at least one urinary tract infection and about a half reported at least one pressure sore since SCI. Almost all took daily medication and about a half reported dry mouth.

Findings on oral health survey

In terms of the upper limb capacity (Table 3), 82% reported the ability to bring at least one hand to the mouth and 65% were able to brush teeth independently and obtain all associated articles, including opening toothpaste. As to daily oral habits, 84 reported brushing teeth, 48 rinsing mouth, 14 flossing, 33 tobacco use and 13 mouthstick use. Only 32% of people with SCI reported teeth cleaning within the past year.

Findings on oral health assessment

The OHS score of >90 (good oral health) was found in 18% of the SCI sample, 80–90 (not that bad) in 29%, 70—80 (treatment is needed) in 21% and <70 (immediate care is necessary) in nearly 32%.

Based on the DMFT scale, the SCI persons had on average three teeth with decay, eight teeth that were missing and four teeth that had been filled, for an average total DMFT score of 15.

The PSR index was 0 in 9% of the SCI sample (no periodontal treatment needed), 1 in 2% (slight gingivitis, oral hygiene instructions needed), 2 or 3 in 12% (professional cleaning and instructions recommended for calculus or tarter build up) and 4 or 5 in 64% (deep scaling needed for shallow to deep pockets). Teeth completely missing in one of the sextants were found in 4% of the sample.

Predictors of oral health

The results of multivariate analysis for OHS, DMFT and PSR as dependent variables are shown in Tables 4, 5, 6. Multiple linear regression revealed that being employed before SCI (P=0.005) and more risky oral habits (P=0.014) were the significant predictors of worse self-perceived oral health (OHS). Negative binomial regression showed that only older age (P<0.001) was a significant predictor of the number of DMFT. Finally, ordered multinomial regression identified again employment status before SCI (P=0.010) and more risky oral habits (P=0.035) as significant predictors of worse periodontal health (PRS). Gender and ethnicity were not significant in any model. Also, none of the selected SCI variables (level, upper limb capacity to independently perform oral hygiene, satisfaction with life, frequency of urinary tract infections) emerged as significant predictors of oral health.

Discussion

This study evaluated oral health in 92 people who sustained SCI at least 6 months earlier and identified significant predictors of oral health. Being employed before injury and more risky oral habits emerged as the two most consistent predictors of worse oral health in people with SCI, with no influence of factors directly related to SCI itself.

This study used three well-accepted dental assessment instruments to evaluate self-perception of oral health and to grade actual dental and periodontal status in people with SCI. Based on self-perception of oral health (OHS score), more than a half of SCI subjects (53%) required treatment or immediate care. This is supported by the findings of two formal examinations, which revealed three decayed and eight missing teeth on average (DMFT score) and the need to perform deep scaling for shallow to deep gingival pockets in the majority of the SCI population (PSR Index). These results extend previous observations made in small samples that people with SCI have increased plaque and gingivitis.27 Of further relevance are previously reported findings in the same population that people with SCI are largely unaware of their dental problems.29 Thus, the majority of people with SCI need to be encouraged to seek preventive care and dental and periodontal treatments.

The need for better preventive care for people with SCI was substantiated by the fact that only 32% had a prophylactic teeth cleaning within the past year. This rate is almost a half of what has been reported for the general population living in the same area (58% in 2006, 60% in 2008, 56% in 2010).37 However, valid comparison between the two groups requires adjustment for some potential confounders (for example, education, income, urbanicity). These findings are also in agreement with previous observations made in a smaller sample that people with SCI are less likely to have annual dental cleanings.28 The overall results support an intuitive impression that SCI population is not receiving the recommended prophylactic dental care. It remains to be determined, however, whether receiving more frequent dental care would translate into better oral health in people with SCI.

The main hypothesis of this study predicted that SCI characteristics (level, upper extremity functional impairment, ability to independently perform oral hygiene) will emerge as the risk factors of compromised oral health (OHS, DMFT, PSR). This was based on the assumption that upper extremity weakness and inability to bring one hand to the mouth for performance of oral hygiene tasks would have a significant impact. However, the results did not confirm this hypothesis. The explanation may be that oral care was provided by a caregiver to those who were unable to do it on their own or that the population of people with severe cervical SCI may have been under sampled. Indeed, most of the participants with high cervical SCI resided in the facility that provides 24-h care.

The two most consistent predictors of compromised oral health after SCI were employment before injury and behaviors that heighten the risk for compromised oral health (not flossing, not rinsing, tobacco use, mouthstick use). These factors predicted both the participants’ self-assessment of oral health (OHS) and the formal examination of periodontal disease (PSR). Older age was the only predictor of DMFT, in agreement with the findings in the general population.7

The interpretation of past employment as a risk factor for worse oral health after SCI is challenging. It also contradicts the assumption that those who had a job in the past were perhaps more likely to have adequate resources, healthier lifestyle and regular dental visits in the past. Unless being a spurious relationship, the history of employment should be considered a proxy. It may be that a history of employment overlapped with older age since these two variables alternated in their significance in all three models.

More intuitive is an explanation for the role of poor oral habits and the use of a mouthstick as predictors of oral health in the SCI population. This emerged from two models, of which one is based on self-perception (OHS) and the other one on formal examination (PSR). Not flossing, rinsing mouth and cleaning teeth regularly are well-recognized risk factors in the general population that evidently carried-over to the SCI population. Not practicing these behaviors may be due to personal attitudes, being overwhelmed with other issues, disturbed mood or time constraints among the caregivers. Oral habits are virtually the only modifiable risk factors identified in this study; therefore, greater effort is needed to stress the importance of good oral habits among people with SCI. Although the use of a mouthstick is encouraged to promote independence and self-efficacy, the mouthstick may harbor bacteria and possibly wear and chip teeth. Thus, greater focus should be placed on mouthstick hygiene and education.

Prevention of oral problems is the most important factor in the care of persons with disabilities.38 Prevention involves increasing personal and caregiver knowledge, regular professional oral care, plaque control, healthy diet and use of fluoride and sealants.16 Many aids have become available to help prevent dental disease, such as saliva substitutes and alcohol free mouth rinses for dry mouth, chlorhexidine gluconate rinses, electric toothbrushes and swabs, which require adaptations and proper education for mechanical debridement.39 The results of this study suggest that these measures should be introduced to and actively promoted among the people with SCI, caregivers and health-care providers.

The limitations of this study are inherent to its exploratory nature and cross-sectional design. Although the sample size was large compared with the previous investigations, the recruited convenience sample is prone to sample bias. The generalization of findings is further limited by the mixed urban and rural study settings and may not adequately reflect other areas.

Conclusion

Oral health appears to be compromised in people with SCI, which suggests the need to focus more attention to the provision of adequate dental and periodontal care to this population. The results could be used to raise awareness among the professionals and people with SCI about the identified modifiable predictors of oral health and the need to practice preventive measures. Identification of modifiable risk factors warrants examining whether interventions with focus on behavioral changes are beneficial in this population. Further studies should also examine barriers to access to dental care and whether adequate training is provided to dental professionals about specific needs of the SCI population.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Allukian M . The neglected epidemic and the surgeon general's report: a call to action for better oral health. Am J Public Health 2000; 90: 843–845.

DeStefano F, Anda RF, Kahn HS, Williamson DF, Russell CM . Dental disease and risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. BMJ 1993; 306: 688–691.

Noack B, Genco RJ, Trevisan M, Grossi S, Zambon JJ, De NE . Periodontal infections contribute to elevated systemic C-reactive protein level. J Periodontol 2001; 72: 1221–1227.

Frisbee SJ, Chambers CB, Frisbee JC, Goodwill AG, Crout RJ . Association between dental hygiene, cardiovascular disease risk factors and systemic inflammation in rural adults. J Dent Hyg 2010; 84: 177–184.

Drummond JR, Newton JP, Yemm R . Dentistry for the elderly: a review and an assessment of the future. J Dent 1988; 16: 47–54.

Davidson PL, Rams TE, Andersen RM . Socio-behavioral determinants of oral hygiene practices among USA ethnic and age groups. Adv Dent Res 1997; 11: 245–253.

Spolsky VW, Marcus M, Coulter ID, Der-Martirosian C, Atchison KA . An empirical test of the validity of the Oral Health Status Index (OHSI) on a minority population. J Dent Res 2000; 79: 1983–1988.

US Department of Health and Human Services NIoDaCRNIoH. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General-Executive Summary 2000.

Cabrera C, Hakeberg M, Ahlqwist M, Wedel H, Bjorkelund C, Bengtsson C et al Can the relation between tooth loss and chronic disease be explained by socio-economic status? A 24-year follow-up from the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol 2005; 20: 229–236.

Drury TF, Garcia I, Adesanya M . Socioeconomic disparities in adult oral health in the United States. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999; 896: 322–324.

Weaver FM, Smith B, Lavela SL, Evans CT, Ullrich P, Miskevics S et al Smoking behavior and delivery of evidence-based care for veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 35–45.

Tomar SL, Asma S . Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol 2000; 71: 743–751.

Muller HP, Stadermann S, Heinecke A . Longitudinal association between plaque and gingival bleeding in smokers and non-smokers. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29: 287–294.

Taybos G . Oral changes associated with tobacco use. Am J Med Sci 2003; 326: 179–182.

Lawton L . Providing dental care for special patients: tips for the general dentist. J Am Dent Assoc 2002; 133: 1666–1670.

Glassman P, Miller CE . Preventing dental disease for people with special needs: the need for practical preventive protocols for use in community settings. Spec Care Dentist 2003; 23: 165–167.

Al-Shammari KF, Al-Khabbaz AK, Al-Ansari JM, Neiva R, Wang HL . Risk indicators for tooth loss due to periodontal disease. J Periodontol 2005; 76: 1910–1918.

Lopez R, Baelum V . Gender differences in tooth loss among Chilean adolescents: socio-economic and behavioral correlates. Acta Odontol Scand 2006; 64: 169–176.

Darby ML, Walsh MM . Dental hygiene theory and practice 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders. 2003.

Post MW, van Leeuwen CM . Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 382–389.

Sjogren R, Nordstrom G . Oral health status of psychiatric patients. J Clin Nurs 2000; 9: 632–638.

Anttila S, Knuuttila M, Ylostalo P, Joukamaa M . Symptoms of depression and anxiety in relation to dental health behavior and self-perceived dental treatment need. Eur J Oral Sci 2006; 114: 109–114.

Friedlander AH, Mahler ME . Major depressive disorder. Psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc 2001; 132: 629–638.

Dmochowski RR, Starkman JS, Davila GW . Transdermal drug delivery treatment for overactive bladder. Int Braz J Urol 2006; 32: 513–520.

Xavier G . The importance of mouth care in preventing infection. Nurs Stand 2000; 14: 47–51.

Stiefel DJ, Truelove EL, Persson RS, Chin MM, Mandel LS . A comparison of oral health in spinal cord injury and other disability groups. Spec Care Dentist 1993; 13: 229–235.

Lancashire P, Janzen J, Zach GA, Addy M . The oral hygiene and gingival health of paraplegic inpatients--a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24: 198–200.

Yuen HK, Azuero A, London S . Association between seeking oral health information online and knowledge in adults with spinal cord injury: a pilot study. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 423–431.

Sullivan AL . Perception of oral status as a barrier to oral care for people with spinal cord injuries. J Dent Hyg 2012; 86: 111–119.

Putzke JD, Barrett JJ, Richards JS, Underhill AT, Lobello SG . Life satisfaction following spinal cord injury: long-term follow-up. J Spinal Cord Med 2004; 27: 106–110.

Burke FJ, Busby M, McHugh S, Delargy S, Mullins A, Matthews R . Evaluation of an oral health scoring system by dentists in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 215–218.

World Health Organization. Oral Health Survey: Basic Methods 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1997.

Anaise JZ . Measurement of dental caries experience--modification of the DMFT index. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1984; 12: 43–46.

Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J . Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN). Int Dent J 1982; 32: 281–291.

Cohen J . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaumm. 1988.

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Office of Management and Budget of the USA Research Service http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/RuralUrbanContinuumCodes/.

Centers for Disease Control Behavior Risk Factor Survelliance System http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/technical_infodata/surveydata/2010.htm.

Stiefel DJ . Dental care considerations for disabled adults. Spec Care Dentist 2002; 22: 26S–39S.

Coleman P . Improving oral health care for the frail elderly: a review of widespread problems and best practices. Geriatr Nurs 2002; 23: 189–199.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Development Fund from School of Health Related Professions, University of Mississippi, Jackson, MS, and the Wilson Research Foundation, Jackson, MS. Dr Sullivan thanks Ray Holder, Jr, DMD, Tracy M Dellinger, DDS, MS, John C Hyde, PhD, and Robin William Rockhold, PhD, for their guidance and support. We thank Jae E Lee, DrPH, for assistance with statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sullivan, A., Bailey, J. & Stokic, D. Predictors of oral health after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 51, 300–305 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.167

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.167

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Software switches: novel hands-free interaction techniques for quadriplegics based on respiration–machine interaction

Universal Access in the Information Society (2020)