Abstract

Study design:

Descriptive case series.

Objectives:

Describe the unusual etiology and pattern of spinal cord injury due to terrorist suicide bombings in Pakistan.

Settings:

Spinal Rehabilitation Unit, Armed Forces Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

Methods:

Hundreds of suicide attacks on civil and military forces have occurred over the last 6 years in Pakistan. These have resulted in thousands of death and many more injured. Six victims of terrorist suicide bombings were admitted over the years 2006 to 2009, who had a spinal cord injury (SCI). This is the first case series of SCI, secondary to terrorist suicide blast.

Results:

All patients were males. The mean age was 30±11 years. Most (five) were injured directly due to splinters from the blast. On admission to rehabilitation, all patients had thoracic complete paraplegia and their SCI was managed conservatively for their spinal injuries. Associated injuries included intestinal perforations, fracture metatarsals, humerus and brachial plexus injury. Pressure ulcer was the commonest complication (3 patients). Two patients had neurological improvement at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion:

Suicide bombing is an effective weapon of terrorists in the modern world of today. The resulting injuries can be diverse and devastating. Spinal cord injury is an uncommon sequel of suicide bombing, which should be kept in mind while dealing with victims of suicide bombing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The past decade has seen the emergence of suicide bombing as a weapon of terrorists in many parts of the world. The Cambridge dictionary defines a suicide bomber as ‘A person who has a bomb hidden on their body and who kills themselves in the attempt to kill others’.1 Suicide bombings have occurred in more than 30 countries of the world.2

In the wake of the ‘war on terror’, Pakistan has been severely affected by suicide terrorism. It is described as world's third worst-hit country in terms of suicide attacks, after Iraq and Afghanistan.2 Hundreds of suicide attacks on civil and military forces over the last 6 years have resulted in thousands of deaths3 and many more injured and permanently disabled.

Methods

An electronic search of Medline with the key words spinal cord injury (SCI), suicide bombing, trauma, terrorism, paraplegia and quadriplegia (Limits: English language only, from 1950 to 2010) located few manuscripts reporting SCI as a consequence of blast injuries, but did not identify any manuscript specifically discussing pattern of SCI resulting from terrorist suicide bombing.

We treated six victims of suicide bombing in the years 2006 to 2009 at the Spinal Rehabilitation Unit, Armed Forces Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine (Rawalpindi, Pakistan), who sustained an SCI as a result of suicide bomb blasts. All patients were referred from the affiliated Spinal Surgery Unit at Combined Military Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. We recorded the demographic data and detailed history to ascertain the nature of the blast, mode of evacuation and initial management. Neurological examination was carried out to determine the completeness and level of SCI according to the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS). Imaging studies were analyzed for the presence or absence of intraspinal canal fragments and for structural spinal injury. Medical case sheets were reviewed. All patients underwent a standard spinal rehabilitation program, with emphasis on physiotherapy, occupational therapy, psychological assessment and counseling and vocational rehabilitation. We observed that the injury pattern of these patients is different and more complex than the pattern reported in the literature. We present an unusual etiological pattern of SCI resulting from terrorist suicide blasts.

The demographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes for the patients are summarized in Table 1. Three case reports are presented in detail.

Case report 1

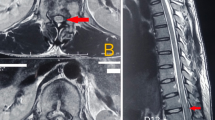

At about 08:30 hours on 8th November 2006, 40 army soldiers were killed and as many injured in suicide bombing in a recruit training area at Dargai, near Mardan (Khyber Pakhtonkhwa Province). Our patient was a 25-year-old, earlier healthy, unmarried male. Following the explosion, he fell on the ground with severe abdominal pain and numbness and paralysis below his waist. He was airlifted to a nearby military hospital, where examination revealed a drowsy young male oozing blood from multiple sites and having tachycardia (112 bpm), and blood pressure of 95/65 mm Hg. There were multiple splinter wounds on right side of abdomen and a single wound on lower back. His abdomen was tender and rigid with absent bowel sounds. He has a T10 AIS grade A SCI. After resuscitation, he underwent emergency laprotomy that revealed a large perforation in the right ascending colon, which was managed with a colostomy. There was no associated visceral or vascular injury. Post-op recovery was unremarkable. Computed tomography scan of the spine revealed shattered pedicle of L5, with a metallic foreign body in right paravertebral region adjacent to the right L4/L5 intervertebral disc. The rest of the vertebral bodies and discs were normal. (Figures 1 and 2) He was transferred to our institute 1-month post SCI. The neurological examination was unchanged as before, with bilateral extensor plantar response and spastic anal tone. He underwent comprehensive spinal cord injury rehabilitation. He received psychotherapy. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction was managed with high roughage diet and manual evacuations, and he was educated in clean intermittent catherisation for bladder management. At 3-year follow-up, there was improvement in the motor function (ASIA A to ASIA C) and sphincter control, although he remained wheelchair-dependent for community.

Case report 3

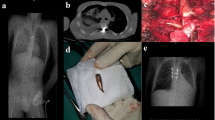

On 30th October 2007, a 25-year-old male van driver had his vehicle hit by the shock wave from a suicide blast, which was blown against a streetlight. Four passengers died at the scene. He was evacuated by an ambulance to the nearby military hospital. On arrival, he reported absent sensation and movement in both legs. Examination was consistent with SCI T11 AIS grade A. Computed tomography scan of spine was suggestive of a fracture dislocation of T12, with severe cord compression. He also had undisplaced fracture of the pubic ramus, along with metallic splinters in the pelvis (Figure 3). Conservative management was planned and he was transferred to the spinal rehabilitation unit at our institute. He underwent 4-months indoor spinal rehab, including therapeutic exercises, occupational therapy, transfer training, bladder and bowel training and psychological counseling. At 6-months follow-up, there was no improvement in the neurological status and patient never returned for subsequent follow-up.

Case report no. 6

At least 35 people were killed and 63 others sustained injuries when a suicide bomber blew himself up outside a bank in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The majority of the blasts victims were reportedly military personnel and employees of the Defense Ministry, who had queued up at the bank to draw their salaries.3 Our patient was a 52-year-old, earlier healthy male. He was rushed in a civilian vehicle to the nearby military hospital. Examination was suggestive of an AIS grade A T7 SCI. He was transferred to our spinal rehabilitation unit after 2 weeks. At the time of admission, his neurological status was same as before, with flaccid lower limbs and absent anal tone and sensations. He had grade IV pressure ulcers on his right greater trochanter and sacrum. His hospital stay was complicated by acute myocardial infarction. His neurological status remained unchanged at 1-year follow-up.

Discussion

In recent years, Pakistan has increasingly been vulnerable to terrorist suicide bombings. These mostly occur in public places (for example, markets, mosques and sports events) and army gatherings (for example, morning parade). These attacks result in loss of life and many injuries, some with severe long-term disability, including SCI.

The pathophysiology, unique pattern of injury, emergency management and outcome of blast injuries has been extensively studied in countries that have suffered terrorist bombings in the last few decades.4, 5, 6, 7 But these do not describe the distinctive SCI pattern secondary to terrorist suicide bombings.

Injuries resulting from suicide bombing are ‘multi-dimensional’,5 that is, victims have more severe and complex injuries, low Glasgow Coma Scale score at presentation and are hemodynamically unstable as compared with victims of conventional trauma. The need for surgical intervention is also increased in terror bombing casualties along with the immediate and late mortalities.4, 7 The injury pattern after a suicide blast depends upon the composition of the bomb (often contains bolts, nails and metal balls) and location (closed locations blasts are more likely to cause severe and large scale injuries).

All the victims of SCI in our case series were males. Table 1 (Figure 4). This can be attributed to the overwhelming presence of males in the armed forces and their role as the prime bread earners in our society. Except for one, all were young males in their second decades and this might have contributed to the better functional and neurological outcomes in most of them completing 1-year follow-up. Most of the SCI were caused by splinters or shrapnels, lodging in the spinal canals and damaging the spinal cord. All patients were managed conservatively. The shrapnel also caused complex-associated injuries, ranging from multiple intestinal perforations, soft tissue injuries, fractures and brachial plexus injury. This associated injury pattern in this case series is more severe than the pattern reported from Pakistan, not related to suicide blasts.8

All patients in this case series had thoracic level injury. There could be two possible explanations:

-

Considering the present state of inadequate evacuation protocols for SCI patients in the country8 and the possibility of complex associated injuries (including abdominal perforations and major blood loss), it would be very unlikely for a cervical injury patient to survive the insult of the suicide bombing attack.

-

In terrorist blast, majority of the casualties occur at the site of the trauma or during first few hours, mainly due to central nervous system or major blood vessels injuries.9

Some of our results are similar to a recent study by Zeili et al.,10 which describes the clinical characteristics and rehabilitation outcomes of civilians with SCI due to terror explosions. Most of their patients had complete thoracic level paraplegia at admission and only three patients showed neurological improvement. Majority of their patients suffered injuries at multiple sites of the body, similar to the pattern observed in our case series.

Limitations of the study

Being an army institute, we primarily receive armed forces personnel. Keeping in view the large number of terrorist suicide blasts in the last few years, especially on the civil population, we believe that the number of SCI is much higher than reported in our case series. Most of the victims do not have access to adequate spinal care, as there is little expertize to manage and rehabilitate SCI in Pakistan and the number of dedicated spinal units in the country is less than five.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt in English biomedical literature to specifically describe SCI demographics and pattern after terrorist's suicide blasts. SCI resulting from suicide blasts are mostly thoracic level with multiple and complex associated injuries.

On the basis of the results, it is suggested that health care institutions at the helm of primary trauma care report the specific injury pattern of terrorist bombings including SCI, observed in our region. A comprehensive national database should be consolidated for future research and insight into SCI including suicide bombing related SCI.

References

Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary online. available from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=103548&dict=CALD (Accessed 5th December 2010).

Suicide attack—Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Available from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicide_attack (Accessed 5th December 2010).

South Asia Terrorism Portal. Fidayeen (Suicide Squad) Attacks in Pakistan. Available from http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/pakistan/database/Fidayeenattack.htm (Accessed 5th December 2010).

Kluger Y, Peleg K, Daniel-Aharonson L, Mayo A . The special injury pattern in terrorist bombings. J Am Coll Surg 2004; 199: 875–879.

Kluger Y . Bomb explosion in acts of terrorism—detonation, wound ballistics, triage and medical concerns. Isr Med Assoc J 2003; 5: 235–240.

Kluger Y, Kashuk J, Mayo A . Bombing—mechanism, consequences and implications. Scand J Surg 2004; 93: 11–14.

Daniel LA, Klein Y, Peleg K . Suicide bombers form a new injury profile. Ann Surg 2006; 244: 1018–1023.

Rathore FA, Hanif S, Farooq F, Butt AW, Ahmed N . Traumatic spinal cord injuries at a tertiary care rehabilitation institute in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 2008; 58: 53–57.

Shapira SC, Levi RA, Avitzour M, Rivkind I, Gertsenshtein I, Mintz Y . Mortality in terrorist attacks: a unique modal of temporal death distribution. World J Surg 2006; 30: 2071–2072.

Zeilig G, Weingarden HP, Zwecker M, Rubin-Asher D, Ratner A, Ohry A . Civilian spinal cord injuries due to terror explosions. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 814–818.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rathore, F., Ayub, A., Farooq, S. et al. Suicide bombing as an unusual cause of spinal cord injury: a case series from Pakistan. Spinal Cord 49, 851–854 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An assessment of existing surge capacity of tertiary healthcare system of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan using workload indicators for staffing need method

Human Resources for Health (2022)

-

Penetrating spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical features and treatment outcomes

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Neglected traumatic spinal cord injuries: experience sharing from Pakistan

Spinal Cord (2013)

-

Factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2013)