Abstract

Habitat selection of animals depends on factors such as food availability, landscape features, and intra- and interspecific interactions. Individuals can show several behavioral responses to reduce competition for habitat, yet the mechanisms that drive them are poorly understood. This is particularly true for large carnivores, whose fine-scale monitoring is logistically complex and expensive. In Scandinavia, the home-range establishment and kill rates of gray wolves (Canis lupus) are affected by the coexistence with brown bears (Ursus arctos). Here, we applied resource selection functions and a multivariate approach to compare wolf habitat selection within home ranges of wolves that were either sympatric or allopatric with bears. Wolves selected for lower altitudes in winter, particularly in the area where bears and wolves are sympatric, where altitude is generally higher than where they are allopatric. Wolves may follow the winter migration of their staple prey, moose (Alces alces), to lower altitudes. Otherwise, we did not find any effect of bear presence on wolf habitat selection, in contrast with our previous studies. Our new results indicate that the manifestation of a specific driver of habitat selection, namely interspecific competition, can vary at different spatial-temporal scales. This is important to understand the structure of ecological communities and the varying mechanisms underlying interspecific interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Habitat selection takes place at several spatial scales, typically described as four orders of selection1. Populations have a distribution range (1st order); individuals establish home ranges (2nd), select habitats inside them (3rd), and use specific patches for specific activities, e.g., feeding and resting (4th). Habitat selection within home ranges depends on factors such as prey availability, landscape features, and intra- and interspecific interactions, which can reduce the selection of otherwise preferred habitats2,3,4. Thus, individual space use is influenced by interactions with other animals and the environment, highlighting the need to jointly investigate the population-level and spatial selection processes underlying such interactions5,6.

Interspecific competition influences the population dynamics and community structure of large carnivores7. Competition triggers different behavioral responses, including varying degrees of spatio-temporal overlap and avoidance among competitors, yet the behavioral mechanisms that drive carnivore responses to competition are poorly understood8. This topic is currently receiving increasing attention for different carnivore guilds in different continents8,9,10,11,12,13. However, the spatio-temporal dynamics of apex predator interactions still requires a better understanding14.

In northern Europe, the gray wolf (Canis lupus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), and wolverine (Gulo gulo) constitute the large carnivore guild. Previous research on interspecific competition focused on their habitat and resource use15,16,17, interference competition between trophic levels18,19, and the demographic impact of coexisting predators on prey20,21. The latter topic has management implications, e.g., to adjust harvest quotas of ungulates in areas with coexisting bears and wolves22.

In Scandinavia (Sweden and Norway), where wolves and bears are forest-living species11, moose constitutes the main prey for wolves all year long, and for bears in spring23,24, which can trigger interactions, e.g., via scavenging of the kills made by each other25,26. The establishment of wolf pairs during the ongoing wolf population recovery, i.e., wolf 2nd order habitat selection, has been affected positively by previous wolf presence and negatively by road density, distance to other wolf territories, and bear density26,27. Proximity to other wolf territories is a proxy of density, which is a major driver of habitat selection28, and road density reflects anthropogenic habitat encroachment, which is also well known as a driver of large carnivore behavior29. However, the negative effect of bear density on the probability of establishment of wolf pairs was a novel finding regarding the effects that interspecific competition between apex predators can have at the population level26,27.

The role of influential factors can vary at different orders of habitat selection, both spatially and temporally2,30,31. For instance, habitat selection of sympatric bobcats (Lynx rufus) and coyotes (Canis latrans) differed slightly at the landscape scale, but not within home ranges32. Seasonal- and scale-related differences have also been shown for ungulates33, and in specific habitat-selection studies of wolves34 and brown bears35,36. In Scandinavia, we have also found that, within home ranges, sympatric wolves and bears segregate more than expected by chance in their habitat selection37, and wolf kill rates are lower when they are sympatric with bears than when not sympatric38. That bear presence triggers different responses of wolves at different spatial scales can be interpreted as a reinforcement of a pattern of behavior30.

To further understand the effects of interspecific competition on large carnivore habitat selection at different spatial contexts, we analyzed the potential variation in wolf habitat selection within home ranges (3rd order of habitat selection) of adult territorial individuals throughout the breeding range of the species in Scandinavia, i.e., when sympatric or allopatric with bears. Based on previous results26,27,37,38, we predicted differences in wolf habitat selection when sympatric compared to allopatric with bears. Because all Scandinavian bears hibernate during winter39, these differences would occur in summer, rather than in winter. Beyond wolves and bears, understanding factors that shape apex predators’ co-occurrence at different scales would help advance our knowledge of the structure of biotic communities.

Methods

Study area

The breeding range of wolves, approx. 100,000 km2 in southcentral Scandinavia, defined our study area (Fig. 1). It consists of an intensively managed coniferous boreal forest, intersected with bogs and lakes. Agricultural land is more common in the south, west, and east of the area. Altitudes range from ~50 to 1000 m above sea level. The density of primary roads within the wolf range is 0.2 + 0.02 km/km2, gravel road density is 4.6 times higher40, and the human population density is low, with <1 person/km2 over large areas26. The wolf population size was ~410 wolves (95% CI 324–533) in the winter of 2017/201841, and average home range size of wolves in Scandinavia is approximately 1000 km242. Wolf packs are sympatric with bears only in the northern part of the study area (61°N, 15°E; Fig. 1). Since 2000/2001, one to eight wolf packs have been recorded annually within the bear range in central Sweden37. Moose densities in Scandinavia are among the highest in the world (~0.5–2 moose per km2) and are the staple prey for wolves, with roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) as secondary prey43. The brown bear population (~2750 bears in 2013) reaches a density of 30 bears/1000 km2 in areas sympatric with wolves44. For context, annual home ranges of adult male bears average ~1000 km2 in the bear core area, five times larger than the ~200 km2 of adult females45. In early summer, neonate moose calves are a primary food item for brown bears in the study area, with most of the predation occurring in May and June23.

Distribution of wolf territories (100% Minimum Convex Polygon) sympatric (within the highlighted circle) or allopatric with brown bears in Scandinavia during 2001–2016. The median elevation range (higher elevation represented by darker background) was typically higher for the northern wolf territories that were sympatric with bears than for the allopatric wolf territories in the south (see Methods). Winter wolf home ranges are displayed in dark blue and spring/summer home ranges in lighter blue. White areas in the lower part of the map represent the biggest lakes in south-central Sweden.

Wolf data and overlap with brown bears

At least one scent-marking adult wolf in each of the studied wolf territories was radio-collared during the last 20 years, to address research and management questions46. For this study, we used data from 25 wolves in 22 wolf territories (44 wolf territory year/seasons), from 2001 to 2016. Wolves were captured with veterinary procedures approved by ethical committees (in Sweden, Djurförsöksetiska nämnd; in Norway, Forsøksdyrutvalget) and the wildlife management authorities (in Sweden, Naturvårdsverket; in Norway, the Norwegian Environment Agency), as described in Arnemo et al.47, i.e., captures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Wolves were equipped with GPS–GSM neck collars (Followit Sweden AB, and VECTRONIC Aerospace GmbH, Germany). Collars recorded locations at 60- or 30-min intervals in late winter/early spring and late spring/early summer, primarily to conduct predation studies38. We did not subset all locations to the same fix interval, because locations were recorded at regular intervals for a given individual and season (either 60 or 30 min) and were therefore proportional to habitat use. Preliminary analyses documented that different fix intervals did not affect the main results. Usually, GPS receivers have an accuracy within 5 m of the actual position under open sky conditions and within 10 m under closed canopies29. We used the distribution of 3083 brown bear deaths, primarily caused by legal hunting, between 1990 and 2012 to create an index of bear density across Scandinavia26. The index was either very close to 0, i.e., in areas with no bears or sporadic bear presence, or >0.8 in areas with the highest bear density, which allowed us to categorize wolf territories as ‘allopatric’ or ‘sympatric’ with bears, respectively (Fig. 1)26,38. We studied wolf habitat selection at the scale of the wolf territory level for territories that were sympatric (N = 15; 9 in winter, 6 in spring-summer) or allopatric (N = 29; 17 in winter, 12 in spring-summer) with brown bears. The elevation range for the centroid of wolf territories sympatric with bears was 194–582 (median = 309) m.a.s.l., whereas it was 34–816 (median = 252) m.a.s.l., for allopatric wolf territories (Fig. 1).

Wolf habitat selection

First, we estimated the home ranges of each wolf territory. Seasonality is important for wolf habitat selection37, thus we differentiated winter (1 December-30 April) and spring/summer (1 May-31 July) habitat selection. Because the periods with intensive GPS locations were limited to late winter, spring, and early summer (for the rest of the year, intervals between consecutive positions were longer to extend the collars’ battery life), the true home range sizes were likely somewhat underestimated42. We therefore defined availability by creating a 100% minimum convex polygon (MCP), for each season and year and for each wolf territory. We then sampled random locations (10 times the number of locations used by the wolves) to define habitat availability within the MCP for each wolf territory. To test the influence of the method chosen to define availability, we also performed the same analysis using 99% kernel home ranges, using the “href” method48. We extracted the habitat characteristics of used and available locations using habitat variables that are known to influence wolf habitat selection, i.e., forest cover, elevation, terrain ruggedness, distance to main and secondary roads, and distance to buildings11,26,37,40 (Table 1). We standardized all variables. We computed the proportion of forest and the terrain ruggedness index using a moving window of 5 × 5 pixels, with a cell resolution of 25 m, i.e., 125 × 125 m around each location.

As we aimed to capture individual variation in habitat selection patterns, we attempted to compute one single resource selection function (RSF) using generalized linear mixed models49 with all individual wolves, including ID of the wolf territory as random intercept, but also random slopes. We followed a five-stages protocol adapted from Bolker 50 to avoid the lack of model convergence. Therefore, we: (1) centered and scaled predictors; (2) checked for singularities; (3) recomputed the Hessian calculation with the Richardson extrapolation method; (4) restarted the fit from the original value; and, (5) attempted all available optimizers. Nevertheless, we did not avoid lack of convergence and, as an alternative, we quantified individual variation in habitat selection by conducting independent RSFs for each wolf territory, using the same set of predictor variables for each territory-season51. We used an exponential function for each territory with the response variable being the used locations (1: GPS locations) and available locations (0: random locations within the home range):

where Xi denotes the collection of covariates i. Coefficients, βi, were estimated using logistic regression52, and exp(βi) can be interpreted as the odds ratio.

Habitat selection can vary based on behavior, i.e., when wolves travel, rest, or handle prey. For example, wolves can use secondary roads for traveling, but not for resting40. Wolves spend about 20% of their time traveling53, and distance between consecutive GPS locations allows distinguishing traveling from other behaviors. Thus, we repeated the same RSFs based on the exponential function described above, but only using the GPS locations when individuals were traveling, to analyze if the potential effect of sympatry/allopatry with bears reflected on a particular wolf behavior. We defined traveling GPS locations as when the speed from the previous location was >200 m/hr. This distance is equivalent to the predation study protocol designed by the Scandinavian Wolf Research Project, which defined clusters of GPS locations as the overlap of at least two buffers with radius of 100 m around each location53.

To further account for a potential effect of habitat availability in wolf habitat selection, we analyzed if there were functional responses on habitat selection, i.e., if wolves selected differently depending on what was available within their respective home ranges. Using the beta coefficients obtained for each individual and each covariate, we linked the habitat selection pattern of each individual for each covariate (i.e., the selection coefficients βi) with the availability of that covariate. Availability was defined by the characteristics of the random locations within the home range of each individual wolf. The assumption behind this analysis was that, without clear functional responses, i.e., with habitat selection not changing with availability, we could compare the coefficients of selection in relation with a particular factor (i.e., brown bear presence/absence in sympatric/allopatric areas, respectively) even if habitat availability regarding other variables could differ among individuals. This analysis revealed a lack of functional responses in wolf habitat selection (Supplementary file).

As a next step, we performed a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the matrix containing the resource selection coefficients of each wolf territory, to visualize the effect of sympatry or allopatry with bears and a potential seasonal effect (winter vs. spring-summer) in wolf habitat selection.

Relationship between wolf habitat selection and sympatry or allopatry with bears

We used generalized linear mixed models49 to investigate the relationship between the habitat selection patterns determined by the RSFs (the scores of the PCA) and whether wolves were sympatric or allopatric with bears. The scores of the main PCA axis were the response variables of our models and the category of wolf territories (sympatric or allopatric) and season (winter or spring-summer) as interacting predictors. If sympatric and allopatric wolf territories showed different habitat selection patterns, we would find a different sign in their estimates for some habitat variables. We conducted this analysis for all GPS locations and then for a subset of the GPS locations of wolves, while traveling. We used the ID of the wolf territory as random intercept with the lmer function and a Gaussian distribution, because some territories were monitored over several seasons/years (Fig. 1). We also included moose density, the wolves’ staple prey, as a covariate in the models. Moose density was extracted from harvest statistics collected at the moose management unit level in Sweden and at the municipality level in Norway, as the average number of moose harvested per km2 inside the wolf territory with a time lag (year t + 1)26,54. We used Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC)55,56 for model selection, considering models within two AIC units as equally supported55. We conducted all analyses with R 3.3.357.

Results

Wolf habitat selection

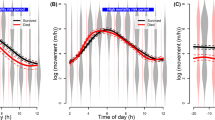

Wolves generally selected for forested and rugged terrain and avoided human-related features of the landscape, i.e., wolves selected for areas further away from main roads and buildings, as illustrated by the estimated coefficients of selection for different habitat variables. This pattern was similar whether using all GPS locations or only the GPS locations of wolves when traveling (Fig. 2). Likewise, the pattern was consistently similar defining habitat availability with MCP (Fig. 2) and kernel methods (Fig. 1a, Supplementary file).

Box plot of the coefficients of selection determined with resource selection functions (RSFs) performed at the wolf territory level for the environmental variables: forest, elevation, rugged terrain (TRI), distance to main and secondary roads, and distance to buildings, using (a) all GPS-locations and (b) only travelling locations. For each variable, the box shows the 1st and 3rd quartile, the horizontal line is the median and the cross is the mean.

Relationship between habitat selection and sympatry or allopatry with bears

The first and second axis of the PCA explained up to 46% and 30%, respectively, of the variation in wolf habitat selection (i.e., ~75% in total, Fig. 3) and were used for further analyses. The PCA showed that wolves with territories in areas sympatric with bears selected for lower elevations in winter. This pattern was similar when using all GPS locations and only those when wolves were traveling, regardless of the alternative definition of habitat availability (MCP or kernel; Fig. 3).

Principal component analysis illustrating wolf habitat selection in Scandinavia in areas sympatric or allopatric with brown bears, using all GPS locations recorded (top panels) and those when wolves were traveling (bottom panels). We used a 100% minimum convex polygon (MCP, left panels) or a 99% kernel home range (right panels) for each wolf territory, to quantify habitat availability. “Elev” is elevation, and all variables are described in Table 1.

As described above (Methods), the scores of the main PCA axis (PC1 and PC2) were the response variables in the regression models. Elevation was the main variable explaining the variation in PC1 (Fig. 3), and the best models confirmed the negative relationship between elevation and wolf habitat selection in winter (Table 2). Avoidance of higher elevation in winter was more consistent for wolf territories sympatric with bears (i.e., the 95% confidence interval around the estimate never included 0) than for wolf territories allopatric with bears (Table 2), thus reaffirming the pattern of avoidance of higher elevation illustrated by the PCA (Fig. 3). The results were consistent and not dependent on alternative definitions of habitat availability (MCP or kernel) or on the type of GPS-locations used (Table 2). Regarding PC2, whose variation was mostly driven by a combination of natural (forest and rugged terrain) and human-related features of the landscape, the null model was the most supported in all cases (Table A2 in Supplementary file). For both PC1 and PC2, the second-best model in each case (with MCP or kernel; with all GPS or only traveling locations) retained the effect of moose density. However, the 95% confidence interval around the estimate of the moose density effect included 0 in all cases, i.e., the direction of the effect was not clear (Table 2 and Table A2), suggesting that moose density per se had relatively little effect on wolf habitat selection, regardless of sympatry or allopatry with bears.

We did not find any other support for different wolf habitat selection within home ranges in areas where wolves were sympatric or allopatric with bears. Our prediction that wolf habitat selection in summer would be different in areas sympatric compared to allopatric with bears was not supported. In contrast, we found that wolf habitat selection differed more clearly in winter between areas sympatric and allopatric with bears (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

We expected wolf habitat selection to be different when sympatric and allopatric with brown bears in Scandinavia in summer, when bears are active, but not in winter, during bear hibernation, but we found the opposite. Differences in wolf habitat selection when sympatric or allopatric with bears were clearer in winter.

Discussion

We have previously found several indications of an effect of the presence of bears on wolf habitat selection in Scandinavia26,27, and that bears and wolves segregate more than expected by chance in their habitat selection37. The present study showed that wolves avoided higher altitudes during winter, particularly in the area where wolf territories were sympatric with bears, i.e., in the northern part of the wolf breeding range in Scandinavia. It is important to note, however, that this area differed from the southern part of the wolf breeding range, where wolves and bears were allopatric, in that the northern part is typically characterized by higher elevation. Because all bears hibernate for 5–7 months in winter in Scandinavia39, interspecific competition with bears may not be the actual driver of wolf avoidance of higher altitudes in winter, even though it has been documented that male bears prefer higher elevation within the forest range for denning36.

In northern Europe, an altitudinal migration of cervids in general, and moose in particular, occurs in winter, with animals moving to lower altitudes to ease movement and increase energy intake58,59,60. Larger altitudinal gradient and moose migration become more common with increasing northern latitude, whereas short altitudinal gradients correspond to shorter horizontal displacement61. Altitudinal moose migration has also been documented where bears and wolves are sympatric in Scandinavia62. Thus, the general occurrence of moose at lower elevations in winter is likely the mechanism explaining our result of wolf avoidance of high elevations in winter63. In our study area, altitude reaches ~1000 m.a.s.l. in the northern part, where wolves and bears are sympatric, whereas most of the wolf territories allopatric with bears are typically found in areas at lower elevations (see Fig. 1 and Methods), with some exceptions on the Norwegian side of the study area.

Wolf kill rates increase with increasing snow depth in some ecosystems, e.g., in Bialowieza (Poland)64 and Michigan (USA)65. However, snow depth was not a significant predictor of wolf kill rates in Yukon (Canada)66 and did not explain variation in hunting success among wolf territories in Scandinavia67. Nevertheless, wolves change movement patterns, sociality, and feeding behavior in response to snow-related changes in prey distribution and mobility68. Thus, it seems reasonable that wolves’ selection of lower altitudes during winter is a result of moose redistribution69, because moose is the main prey in the northern part of the Scandinavian wolf range70.

We have previously found that wolves and bears segregate more than expected by chance within home ranges where both species are sympatric in Scandinavia, particularly in late spring and early summer, when both predators rely on neonate moose calves37. Nevertheless, in that study we found both similarities and differences in wolf and bear habitat selection. In particular, wolves, an obligate carnivore, selected for habitats with higher moose densities than bears did37. The observed wolf avoidance of higher altitudes in winter in this present study seems to reinforce the tight relation between wolf habitat selection and the habitat selection of their staple prey, moose, which in Scandinavia occur in high densities compared to other areas67.

In Scandinavia, wolves and bears compete seasonally for the same resource, i.e., neonate moose calves, which are born and heavily preyed upon by both predators in spring and early summer. This competition could affect habitat selection37 and wolf kill rates, which are lower in areas sympatric with bears than in allopatric areas38. In the present study, and against our prediction (Fig. 4), we found no differences in wolf habitat selection in spring-summer for wolf territories sympatric or allopatric with bears as an apparent effect of interspecific interaction between these apex predators. This indicates that a given driver of habitat selection can have varying influence at different spatial scales30, and highlights the importance of seasonality to understand interspecific interactions31,37.

Regardless of sympatry or allopatry with bears, wolves generally selected for forested and rugged terrain and avoided human-related features of the landscape. This general pattern was very similar when using all GPS locations or only those recorded while traveling, and with different definitions of habitat availability (MCP/kernel; Fig. 2 and Fig. 1a, respectively). This is in line with previous findings for this and other large carnivore populations, e.g., in Scandinavia26,27, and suggests that our variables were adequate to find a pattern of wolf habitat selection in agreement with previously published literature. However, this does not necessarily mean that our variables represented all factors that can influence wolf habitat selection. The very large spatial and temporal scale of our study, performed across ~100,000 km2 and a 15–year time span, may imply that some unmeasured factors masked or overrode the potential effect of interspecific competition with bears at this large scale, for instance. It is noteworthy, however, that forest cover and road and building densities did not change over the study period and, most remarkably given the goal of the study, bear density has been stable since the 1990’s in the study area26, i.e., the variables we included were robust. Intraspecific factors, such as wolf density, also drive wolf habitat selection26; e.g., the effect of natal habitat imprinting on wolf habitat selection during the dispersal phase and later in life has recently been documented27,71.

Human avoidance is indeed an overwhelming factor explaining large carnivore habitat selection in human-dominated landscapes, and wolves are no exception26,72,73. Although bear density has a negative effect on the probability of wolf pair establishment in Scandinavia, avoidance of main roads is even more important26. Likewise, both bears and wolves avoid human-related habitats within their home ranges during daytime37.

In this study, wolves generally selected against human-related features of the landscape throughout the study area and against higher elevations in winter, particularly in the northern area, where bears and wolves overlap. The latter result may be explained by moose seasonal distribution and the typically higher elevation in the northern part of our study area, which results in a deeper snow cover in winter than in the southern part of the area74. Nevertheless, we suggest that it is worth highlighting the value of the apparent lack of an effect of the presence of bears on habitat selection by territorial, adult wolves in our present study. Communication or publication of scientific results is easier when results are positive and novel than when they are negative, confirmatory, or merely supportive of null hypotheses75. However, negative results can lead researchers to critically evaluate and validate their way of thinking76. In this context, the lack of an effect of bears in our study, in contrast to previous results, illustrates empirically that a given driver of habitat selection can play a different role at different spatial and seasonal scales contexts, as suggested earlier30. Because of the scarcity of studies on interspecific competition between large carnivores at the population level, finding a varying effect of interspecific competition, i.e., a varying effect of bear presence on wolf habitat selection at different spatial and temporal context, is relevant to understanding the complex structure of ecological communities and mechanisms underlying interactions.

Accounting for availability is crucial in habitat selection studies77. In this study, we compared the habitat selection pattern of individuals whose available resources varied depending on where they had established their territories. As shown in the Supplementary file, we found no evidence for the presence of functional responses in the wolves’ habitat selection in relation to habitat availability78. This means that individuals did not seem to change their behavior according to resource availability. Without functional responses, i.e., with habitat selection not changing with availability, we suggest we can compare the coefficients of selection in relation with a given factor (namely, brown bear presence/absence in sympatric/allopatric areas, respectively), even if habitat availability regarding other variables differed among individuals.

Finally, most of the individual wolf-bear interactions described in the literature have been observed at carcasses79, and fine-scale movements around kill sites may be another mechanism used to reduce the risk of encounters and interactions between sympatric predators37. Thus, to complement studies at second and third order of habitat selection, including previous studies26,27,37 and this one, we emphasize that future studies should explore the potential effect of interspecific interactions at the fourth order of habitat selection and in relation with other behaviors. For instance, analyzing the potential effect of interspecific interactions at resting and kill sites in areas sympatric or allopatric with brown bears in general, and with different sex and age classes of bears in particular. Although rare, remains of puppies and cubs of wolves and bears, respectively, have been found in scats of the other predator79,80, thus analyzing potential interactions at breeding dens of both species and at rendezvous sites of wolves could also be interesting. Such studies would provide further knowledge of the potential effect of interactions at finer spatial scales and in relation with specific behaviors, such as resting, foraging, and breeding.

Data availability

Data would be made available on Dryad Digital Repository.

References

Johnson, D. H. The comparison of usage and availability measurements for evaluating resource preference. Ecology 61, 65–71 (1980).

Gaillard, J. et al. Habitat – performance relationships: finding the right metric at a given spatial scale. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 365, 2255–2265 (2010).

Davidson, Z. et al. Environmental determinants of habitat and kill site selection in a large carnivore: scale matters. J. Mammal. 93, 677–685 (2012).

Rostro-García, S., Kamler, J. F. & Hunter, L. T. B. To kill, stay or flee: The effects of lions and landscape factors on habitat and kill site selection of cheetahs in South Africa. PLoS One 10, 1–20 (2015).

Horne, J. S., Garton, E. O. & Rachlow, J. L. A synoptic model of animal space use: Simultaneous estimation of home range, habitat selection, and inter/intra-specific relationships. Ecol. Modell. 214, 338–348 (2008).

Potts, J. R., Mokross, K. & Lewis, M. A. A unifying framework for quantifying the nature of animal interactions. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140333 (2014).

Caro, T. M. & Stoner, C. J. The potential for interspecific competition among African carnivores. Biol. Conserv. 110, 67–75 (2003).

Vanak, A. T. et al. Moving to stay in place: Behavioral mechanisms for coexistence of African large carnivores. Ecology 94, 2619–2631 (2013).

de Oliveira, T. G. & Pereira, J. A. Intraguild Predation and Interspecific Killing as Structuring Forces of Carnivoran Communities in South America. J. Mamm. Evol. 21, 427–436 (2014).

Kortello, A. D., Hurd, T. E. & Murray, D. L. Interactions between cougars (Puma concolor) and gray wolves (Canis lupus) in Banff National Park. Ecoscience 14, 214–222 (2007).

May, R. et al. Habitat differentiation within the large-carnivore community of Norway’s multiple-use landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 45, 1382–1391 (2008).

Lovari, S., Pokheral, C. P., Jnawali, S. R., Fusani, L. & Ferretti, F. Coexistence of the tiger and the common leopard in a prey-rich area: The role of prey partitioning. J. Zool. 295, 122–131 (2015).

Allen, B. L., Allen, L. R. & Leung, L. K. P. Interactions between two naturalised invasive predators in Australia: are feral cats suppressed by dingoes? Biol. Invasions 17, 761–776 (2014).

Périquet, S., Fritz, H. & Revilla, E. The lion king and the hyaena queen: Large carnivore interactions and coexistence. Biol. Rev. 90, 1197–1214 (2015).

Wikenros, C., Liberg, O., Sand, H. & Andrén, H. Competition between recolonizing wolves and resident lynx in Sweden. Can. J. Zool. 88, 271–279 (2010).

Mattisson, J., Andrén, H., Persson, J. & Segerström, P. Influence of intraguild interactions on resource use by wolverines and Eurasian lynx. J. Mammal. 92, 1321–1330 (2011).

Rauset, G. R., Mattisson, J., Andrén, H., Chapron, G. & Persson, J. When species’ ranges meet: Assessing differences in habitat selection between sympatric large carnivores. Oecologia 172, 701–711 (2013).

Elmhagen, B., Ludwig, G., Rushton, S. P., Helle, P. & Lindén, H. Top predators, mesopredators and their prey: Interference ecosystems along bioclimatic productivity gradients. J. Anim. Ecol. 79, 785–794 (2010).

Wikenros, C., Ståhlberg, S. & Sand, H. Feeding under high risk of intraguild predation: vigilance patterns of two medium-sized generalist predators. J. Mammal. 95, 862–870 (2014).

Andrén, H., Persson, J., Mattisson, J. & Danell, A. C. Modelling the combined effect of an obligate predator and a facultative predator on a common prey: lynx Lynx lynx and wolverine Gulo gulo predation on reindeer Rangifer tarandus. Wildlife Biol. 17, 33–43 (2011).

Gervasi, V. et al. Predicting the potential demographic impact of predators on their prey: a comparative analysis of two carnivore-ungulate systems in Scandinavia. J. Anim. Ecol. 81, 443–454 (2012).

Jonzén, N. et al. Sharing the bounty—Adjusting harvest to predator return in the Scandinavian human–wolf–bear–moose system. Ecol. Modell. 265, 140–148 (2013).

Swenson, J. et al. Predation on Moose Calves by European Brown Bears. J. Wildl. Manage. 71, 1993–1997 (2007).

Sand, H. et al. Summer kill rates and predation pattern in a wolf-moose system: Can we rely on winter estimates? Oecologia 156, 53–64 (2008).

Milleret, C. Estimating wolves (Canis lupus) and brown Bear (Ursus arctos) interactions in Central Sweden. Does the emergence of brown bears affect wolf predation patterns? (Master thesis. Université Joseph Fourier – Grenoble, 2011).

Ordiz, A. et al. Wolves, people, and brown bears influence the expansion of the recolonizing Wolf population in Scandinavia. Ecosphere 6, 1–14 (2015).

Sanz-Pérez, A. et al. No place like home? A test of the natal habitat-biased dispersal hypothesis in Scandinavian wolves. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5, 181379 (2018).

van Beest, F. M. et al. Increasing density leads to generalization in both coarse-grained habitat selection and fine-grained resource selection in a large mammal. J. Anim. Ecol. 83, 147–156 (2014).

Ordiz, A., Kindberg, J., Sæbø, S., Swenson, J. E. & Støen, O. G. Brown bear circadian behavior reveals human environmental encroachment. Biol. Conserv. 173, 1–9 (2014).

Rettie, W. J. & Messier, F. Hierarchical habitat selection by woodland caribou: its relationship to limiting factors. Ecography (Cop.). 23, 466 (2000).

Basille, M., Fortin, D., Dussault, C., Ouellet, J. P. & Courtois, R. Ecologically based definition of seasons clarifies predator-prey interactions. Ecography (Cop.). 36, 220–229 (2013).

Neale, J. C. C. & Sacks, B. N. Resource utilization and interspecific relations of sympatric bobcats and coyotes. Oikos 94, 236–249 (2001).

Owen-Smith, N., Martin, J. & Yoganand, K. Spatially nested niche partitioning between syntopic grazers at foraging arena scale within overlapping home ranges. Ecosphere 6, 152 (2015).

Uboni, A., Smith, D. W., Mao, J. S., Stahler, D. R. & Vucetich, J. A. Long- and short-term temporal variability in habitat selection of a top predator. Ecosphere 6, 1–16 (2015).

Steyaert, S. M. J. G., Kindberg, J., Swenson, J. E. & Zedrosser, A. Male reproductive strategy explains spatiotemporal segregation in brown bears. J. Anim. Ecol. 82, 836–845 (2013).

Eriksen, A., Wabakken, P., Maartmann, E. & Zimmermann, B. Den site selection by male brown bears at the population’s expansion front. PLoS One 13(8), e0202653 (2018).

Milleret, C. et al. Habitat segregation between brown bears and gray wolves in a human-dominated landscape. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1–17 (2018).

Tallian, A. et al. Competition between apex predators? Brown bears decrease wolf kill rate on two continents. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 284, 20162368 (2017).

Swenson, J. E., Adamic, M., Huber, D. & Stokke, S. Brown bear body mass and growth in northern and southern Europe. Oecologia 153, 37–47 (2007).

Zimmermann, B., Nelson, L., Wabakken, P., Sand, H. & Liberg, O. Behavioral responses of wolves to roads: Scale-dependent ambivalence. Behav. Ecol. 25, 1353–1364 (2014).

Wabakken, P., Svensson, L., Maartmann, E., Åkesson, M. & Flagstad, Ø. Wolf monitoring in Scandinavia, 2017–2018. Rovdata and Viltskadecenter (2018).

Mattisson, J. et al. Home range size variation in a recovering wolf population: Evaluating the effect of environmental, demographic, and social factors. Oecologia 173, 813–825 (2013).

Sand, H., Eklund, A., Zimmermann, B., Wikenros, C. & Wabakken, P. Prey selection of Scandinavian wolves: Single large or several small? PLoS One 11, e0168062 (2016).

Swenson, J. E. et al. Challenges of managing a European brown bear population; lessons from Sweden, 1943–2013. Wildlife Biol. 1, wlb.00251 (2017).

Dahle, B. & Swenson, J. E. Home ranges in adult Scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos): Effect of mass, sex, reproductive category, population density and habitat type. J. Zool. 260, 329–335 (2003).

Liberg, O. et al. Monitoring of wolves in Scandinavia. Hystrix 23, 29–34 (2012).

Arnemo, J. et al. Biomedical protocols for free-ranging Brown bears, Gray wolves, wolverines and lynx. (Norwegian School of Veterinary Science, Tromsø, Norway, 2007).

Worton, B. J. Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home-range studies. Ecology 70, 164–168 (1989).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using {lme4}. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Bolker, B. Mixedmodels-misc; Miscellaneous materials for mixed models, mostly in R. (2019). Available at: https://bbolker.github.io/mixedmodels-misc.

Thurfjell, H., Ciuti, S. & Boyce, M. S. Applications of step-selection functions in ecology and conservation. Mov. Ecol. 2, 1–12 (2014).

Manly, B., McDonald, L., Thomas, D., McDonald, T. & Erickson, W. Resource selection by animals. Statistical design and analysis for field studies. (Kluwer, 2002).

Zimmermann, B., Wabakken, P., Sand, H., Pedersen, H. & Liberg, O. Wolf movement patterns: a key to estimation of kill rate? J. Wildl. Manage. 71, 1177–1182 (2007).

Ueno, M., Solberg, E. J., Iijima, H., Rolandsen, C. M. & Gangsei, L. E. Performance of hunting statistics as spatiotemporal density indices of moose (Alces alces) in Norway. Ecosphere 5, 13 (2014).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model selection and multi-model inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. (Springer Verlag, 2002).

Zuur, A., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. (Springer, 2009).

R Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2017). Available at: https://www.r-project.org/.

Mysterud, A., Langvatn, R., Yoccoz, N. G. & Stenseth, N. C. H. R. Plant phenology, migration and geographical variation in body weight of a large herbivore: the effect of a variable topography. J. Anim. Ecol. 70, 915–923 (2001).

Gundersen, A. H. et al. Supplemental feeding of migratory moose Alces alces: forest damage at two spatial scales. Wildlife Biol. 10, 213–223 (2004).

Bunnefeld, N. et al. A model-driven approach to quantify migration patterns: individual, regional and yearly differences. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 466–476 (2011).

Singh, N. J. et al. From migration to nomadism: movement variability in a northern ungulate across its latitudinal range. Ecol. Appl. 22, 2007–2020 (2012).

Cederlund, G., Sandegren, F. & Larsson, K. Summer movements of female moose and dispersal of their offspring. J. Wildl. Manage. 51, 342–352 (1987).

Carricondo-Sanchez, D. et al. Wolves at the door? Factors influencing the individual behavior of wolves in relation to anthropogenic features. Biol. Conserv. 244, 108514 (2020).

Jedrzejewski, W. et al. Kill rates and predation by wolves on ungulates in Bialowieza Primeval Forest (Poland). Ecology 83, 1341–1356 (2002).

Vucetich, J. A., Huntzinger, B. A., Peterson, R. O., Vucetich, L. M. & Al., E. Intra-seasonal variation in wolf Canis lupus kill rates. Wildlife Biol. 18, 235–245 (2012).

Hayes, R. D., Baer, A. M., Wotschikowsky, U. & Harestad, A. S. Kill rate by wolves on moose in the Yukon. Can. J. Zool. 78, 49–59 (2000).

Sand, H., Wikenros, C., Wabakken, P. & Liberg, O. Effects of hunting group size, snow depth and age on the success of wolves hunting moose. Anim. Behav. 72, 781–789 (2006).

Fuller, T. Effect of snow depth on wolf activity and prey selection in north central Minnesota. Can. J. Zool. 69, 283–287 (1991).

Allen, A. M. & Singh, N. J. Linking movement ecology with wildlife management and conservation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1–13 (2016).

Zimmermann, B., Sand, H., Wabakken, P., Liberg, O. & Andreassen, H. Predator-dependent functional response in wolves: from food limitation to surplus killing. J. Anim. Ecol. 84, 102–112 (2015).

Milleret, C. et al. Testing the influence of habitat experienced during the natal phase on habitat selection later in life in Scandinavian wolves. Sci. Rep. 9(6526), 1–11 (2019).

Kaartinen, S., Kojola, I. & Colpaert, A. Finnish wolves avoid roads and settlements. Ann. Zool. Fennici 42, 523–532 (2005).

Ciucci, P., Boitani, L., Falco, M. & Maiorano, L. Hierarchical, multi-grain rendezvous site selection by wolves in southern Italy. J. Wildl. Manage. 82, 1049–1061 (2018).

Cresso, M. & Frid, M. Historical daily snowfall and extremes in Sweden, can a model simulate that? observations and model simulations. (Thesis. University of Gothenburg, 2017).

Editorial Nature. Nurture negatives. 551, 414 (2017).

Matosin, N., Frank, E., Engel, M., Lum, J. S. & Newell, K. A. Negativity towards negative results: a discussion of the disconnect between scientific worth and scientific culture. Dis Model Mech 7, 171–173 (2014).

Lele, S. R., Merrill, E. H., Keim, J. & Boyce, M. S. Selection, use, choice and occupancy: Clarifying concepts in resource selection studies. J. Anim. Ecol. 82, 1183–1191 (2013).

Mysterud, A. & Ims, R. A. Functional responses in habitat use: Availability influences relative use in trade-off situations. Ecology 79, 1435–1441 (1998).

Ballard, W., Carbyn, L. N. & Smith, D. W. Wolf interactions with non-prey. in Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation (ed. LD Mech & L Boitani) 259–271 (University of Chicago Press., 2003).

Capitani, C., Chynoweth, M., Kusak, J., Çoban, E. & Sekercioǧlu, Ç. H. Wolf diet in an agricultural landscape of north-eastern Turkey. Mammalia 80, 329–334 (2016).

Sappington, J., Longshore, K. M. & Thompson, D. B. Quantifying landscape ruggedness for animal habitat analysis: a case study using bighorn sheep in the Mojave Desert. J. Wildl. Manage. 71, 1419–1426 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to everyone monitoring wolves and bears in Scandinavia for several decades, including the teams that captured and handled the animals. GPS data was collected into the Wireless Remote Animal Monitoring (Dettki, Ericsson, Giles, & Norrsken‐Ericsson, 2013) database system for data validation and management. The Scandinavian wolf and bear research projects (SKANDULV and SBBRP, respectively) have been funded by the Norwegian Environment Agency, Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Norwegian Research Council, Swedish Research Council Formas, Austrian Science Fund, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Office of Environmental Affairs in Hedmark County, Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management, WWF (Sweden), Swedish Carnivore Association, Olle and Signhild Engkvists Foundations, Carl Tryggers Foundation, and Marie‐Claire Cronstedts Foundation. We are grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for useful comments and suggestions during the review process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.O., H.S. and C.M. conceived the study; A.O. wrote the manuscript and A.U. carried out statistical analysis, with contribution of C.M. and A.S.P. B.Z., C.W., P.W., J.K., J.E.S. and H.S. coordinated and secured funding for the long-term research on bears and wolves. Everyone helped draft the manuscript and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ordiz, A., Uzal, A., Milleret, C. et al. Wolf habitat selection when sympatric or allopatric with brown bears in Scandinavia. Sci Rep 10, 9941 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66626-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66626-1

This article is cited by

-

Applying XGBoost and SHAP to Open Source Data to Identify Key Drivers and Predict Likelihood of Wolf Pair Presence

Environmental Management (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.