Abstract

GUCA1A gene variants are associated with autosomal dominant (AD) cone dystrophy (COD) and cone-rod dystrophy (CORD). GUCA1A-associated AD-COD/CORD has never been reported in the Japanese population. The purpose of this study was to investigate clinical and genetic features of GUCA1A-associated AD-COD/CORD from a large Japanese cohort. We identified 8 variants [c.C50_80del (p.E17VfsX22), c.T124A (p.F42I), c.C204G (p.D68E), c.C238A (p.L80I), c.T295A (p.Y99N), c.A296C (p.Y99S), c.C451T (p.L151F), and c.A551G (p.Q184R)] in 14 families from our whole exome sequencing database composed of 1385 patients with inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) from 1192 families. Three variants (p.Y99N, p.Y99S, and p.L151F), which are located on/around EF-hand domains 3 and 4, were confirmed as “pathogenic”, whereas the other five variants, which did not co-segregate with IRDs, were considered “non-pathogenic”. Ophthalmic findings of 9 patients from 3 families with the pathogenic variants showed central visual impairment from early to middle-age onset and progressive macular atrophy. Electroretinography revealed severely decreased or non-recordable cone responses, whereas rod responses were highly variable, ranging from nearly normal to non-recordable. Our results indicate that the three pathogenic variants, two of which were novel, underlie AD-COD/CORD with progressive retinal atrophy, and the prevalence (0.25%, 3/1192 families) of GUCA1A-associated IRDs may be low among Japanese patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The guanylate cyclase activator 1A (GUCA1A) gene (OMIM *600364) encodes for guanylyl cyclase-activating protein 1 (GCAP-1), which is expressed in both rod and cone outer segments1 and regulates synthesis of cGMP from GTP via retinal guanylate cyclase (RetGC) encoded by the retinal guanylate cyclase 2D (GUCY2D) gene2,3. GCAP-1 has four EF-hand domains, three (EF-2, EF-3, and EF-4) of which exhibit Ca2+/Mg2+ binding and act as Ca2+/Mg2+ sensor proteins4,5,6. Each EF-hand domain (EF-2, EF-3, and EF-4) consists of a helix-loop-helix secondary structure that is able to chelate Ca2+, whereas EF-1 domain serves as a target-binding domain. In the dark-adapted state, when cytosolic Ca2+ concentration is high, GCAP-1 binds Ca2+ and inhibits RetGC activity and cGMP synthesis. cGMP is hydrolyzed by light-activated phosphodiesterase in the light-adapted state, leading to closure of cation channels and low cytosolic Ca2+ concentration7,8 in which GCAP-1 releases Ca2+. Then, Mg2+ binds to the EF-2 and/or EF-3 in the Ca2+-free state of GCAP-1, and the Mg2+-bound GCAP-1 activates RetGC. Interestingly, mutated GCAP-1 (e.g. p.Y99C, p.D100E, p.L151F) associated with disease-causing GUCA1A variants show persistently stimulated RetGC activity, leading to the elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ and cGMP concentrations and resulting in initiation of photoreceptor cell death9,10,11,12,13.

Heterozygous GUCA1A variants have been reported as causes of autosomal dominant (AD) macular dystrophy (MD), cone dystrophy (COD), and cone-rod dystrophy (CORD)9,14,15,16,17,18. Previous studies have revealed that most patients with GUCA1A variants finally exhibit a CORD phenotype with progressive macular atrophy14,15,19,20. To date, all reported GUCA1A variants are missense or in-frame insertion/deletion types, according to the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/). A large US cohort study of inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) has revealed the prevalence of GUCA1A-associated IRD is 0.7% (7/1000 families)21. However, to our knowledge, IRDs associated with GUCA1A variants have never been reported in the Japanese population22.

In this study, we identified rare GUCA1A variants from our whole exome sequencing (WES) database composed of IRD patients from a large Japanese cohort. The purpose of this study was to investigate the pathogenicity of rare GUCA1A variants and clinical and genetic features of GUCA1A-associated IRDs.

Results

Genetic analysis

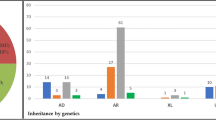

We identified eight rare GUCA1A variants [c.C50_80del (p.E17VfsX22), c.T124A (p.F42I), c.C204G (p.D68E), c.C238A (p.L80I), c.T295A (p.Y99N), c.A296C (p.Y99S), c.C451T (p.L151F), and c.A551G (p.Q184R)] from 14 unrelated families after filtering (Supplementary Table S1). According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria, three variants (p.Y99N, p.Y99S, and p.L151F) from three families (NTMC 244, JIKEI 136, and JIKEI 215) were confirmed as “pathogenic” (Fig. 1A,B). Two (p.Y99N and p.Y99S) of the 3 variants were novel, while the remaining variant (p.L151F) was previously reported as the cause of AD-CORD16,19. The 3 variants co-segregated with the disease and were located on/around EF-hand domain 3 or 4, which is essential for cytosolic Ca2+/Mg2+ binding (Fig. 1C). In silico programs predicted severe damage to GCAP-1 (Supplementary Table S1), and each affected patient was diagnosed with COD/CORD. In our WES analysis, no other pathogenic variant, which is listed in the RetNet database, was found in the 3 families (NTMC 244, JIKEI 136, and JIKEI 215). In contrast, the other 5 variants (p.E17VfsX22, p.F42I, p.D68E, p.L80I, and p.Q184R) identified in 11 families were classified as “uncertain significance” according to the ACMG criteria (Supplementary Table S1). All 5 variants were located outside of EF-hand domains 3 and 4 (Fig. 1C) and did not segregate with the disease; therefore, these variants were considered to be “non-pathogenic”.

Pedigree charts of three Japanese families with GUCA1A-associated cone-rod dystrophy, nucleotide sequences of GUCA1A variants, and amino acid sequence alignment of GCAP-1 in different vertebrate species. (A) Solid squares (males) and circles (females) represent affected patients. Open squares (males) and circles (females) represent unaffected individuals. The proband of each family is indicated by an arrow. (B) Heterozygous variants [c.296 A > C (p.Y99S), c.295 T > A (p.Y99N), and c.451 C > T (p.L151F)] are shown in patients of families 1, 2, and 3, respectively. (C) The conserved 12-amino acid Ca2+ binding loop of EF-hand domains 3 and 4 are highlighted by gray shading. EF-hand domains 1 and 2 are surrounded by rectangles. Variants identified in this study are indicated by arrows.

Clinical study

In 3 families with the pathogenic GUCA1A variants (p.Y99S, p.Y99N, and p.L151F), a total of 9 affected patients were clinically investigated (Fig. 1A). The examined age ranged from 15 to 69 years old (mean age: 43.0 years, standard deviation: 18.3 years). Clinical findings of the 9 affected patients are summarized in Table 1.

Onset, initial symptoms, and visual acuity

The age of onset ranged from 3 to 30 years old (mean age: 14.6 years, standard deviation: 9.6 years). Initial symptoms were available from 9 patients and included reduced visual acuity (9/9, 100%), photophobia (3/9, 33.3%), and central visual field loss (1/9; 11.1%). The decimal best-corrected visual acuity of the nine patients ranged from 0.01 to 0.8 at the examined age (Table 1).

Fundus photographs, FAF, and OCT findings

Each examination showed variable degrees of retinal abnormalities (Fig. 2) and we classified the abnormalities into early, middle, and advanced stages according to the severity of macular atrophy. Patient F2: III-1 was classified into early stage and exhibited discoloration and slight hyper-autofluorescence limited at the fovea in fundus and FAF images and preserved hyper-reflectivity of the ellipsoid zone (EZ) with the foveal bulge in OCT images. Two patients (F3: II-1 and F3: II-2) were classified into middle stage and exhibited almost normal fundus appearance or slight macular atrophy in fundus photographs, hyper-autofluorescent ring around the fovea in FAF images, and diffusely decreased or disrupted EZ without the foveal bulge in OCT images. Patient F2: II-1 was also classified into middle stage and exhibited macular atrophy in fundus photographs, hypo-autofluorescent area corresponding to retinal atrophy with hyper-autofluorescence around the area in FAF images, and diffusely decreased or disrupted EZ without the foveal bulge in OCT images. Five patients (F1: II-2, F1: I-2, F2: II-2, F2: I-1, and F3: I-1) were classified into advanced stage and exhibited retinal atrophy at the macula or posterior pole in fundus photographs, loss of autofluorescent area corresponding to retinal atrophy with hyper-autofluorescence around the area in FAF images, and disrupted EZ and thinning of the outer retina corresponding to the retinal atrophic area with hypo-reflectivity of the EZ outside the area in OCT images.

Fundus photographs, fundus autofluorescence imaging, and optical coherence tomography images. Each patient showed variable degrees of macular atrophy. Nine patients were classified into three stages (early stage: retinal abnormalities limited at the fovea, middle stage: retinal abnormalities within the macular area and advanced stage: retinal abnormalities beyond the macular area) based on the severity of macular atrophy. One patient (F2: III-1) had early stage abnormality, three patients (F3: II-1, F3: II-2, and F2: II-1) had middle stage abnormalities, and five patients (F1: II-2, F1: I-2, F2: II-2, F2: I-1, and F3: I-1) had advanced stage abnormalities.

The atrophic areas were apparently more enlarged in older patients (i.e., 15-year-old patient F2: III-1 at the early stage, mean age of 33.3 years in the middle stage, and mean age of 54.4 years in the advanced stage). In addition, the enlargement pattern of the atrophic area was different between family 1 and the other 2 families. Retinal atrophy in family 1 extended over the optic disc and inferior arcade whereas that in families 2 and 3 showed elliptical enlargement within the vascular arcade.

Visual field findings

The results of visual field testing were obtained from 14 eyes of 7 patients. All 7 patients exhibited central visual field loss corresponding to retinal abnormalities. Patient F2: III-1 with early stage abnormality showed normal visual field in the right eye and slightly decreased central sensitivity in the left eye in HFA. The other six patients were examined using GP. Two patients with middle stage abnormalities showed central scotoma of V-4e isopter in the right eye (F3: II-2) and central scotoma of I-4e isopter in three eyes (both eyes of F3: II-1 and the left eye of F3: II-2). One patient with middle stage abnormality and two patients with advanced stage abnormalities showed central scotoma of V-4e isopter in all eyes (F2: II-1, F1: II-2, and F2: II-2), and one patient with advanced stage abnormality showed central visual field loss in both eyes (F1: I-2). The areas of central scotomas were consistent with the lesions of retinal atrophy.

Four (F1: II-2, F2: II-2, F3: II-1, and F3: II-2) of 5 patients, whose retinal atrophy was limited to the posterior pole, showed preserved peripheral visual fields. In contrast, patients F2: II-1 and F1: I-2 exhibited constriction of the peripheral visual field and an island limited to the inferior area.

Full-filed electroretinographic findings

Full-field (FF)-electroretinography (ERG) recording was performed in 16 eyes of 8 patients. The results showed severely decreased or non-recordable cone responses in all patients (Fig. 3). Regarding rod responses, three patients (F2: III-1, F3: II-1, and F3: II-2) with early to middle stage abnormalities exhibited preserved rod responses, whereas 5 patients (F1: I-2, F1: II-2, F2: II-2, F2: II-1, and F3: I-1) with advanced stage abnormalities exhibited decreased and non-recordable rod responses, respectively (Fig. 3).

Full-field electroretinography findings. Full-field electroretinography (FF-ERG) shows severely decreased or non-recordable light-adapted cone and 30-Hz flicker responses in all eight examined patients. Dark-adapted rod and combined rod-cone/flash ERG findings show preserved responses in three patients (F2: III-1, F3: II-1, and F3: II-2), decreased responses in four patients (F1: II-2, F2: II-2, F2: II-1, and F3: I-1), and non-recordable responses in one patient (F1: I-2).

Discussion

In this study, eight rare GUCA1A variants, three of which were pathogenic, were identified in our large Japanese cohort. Furthermore, we demonstrated clinical features of nine COD/CORD patients from three unrelated Japanese families with two novel variants (p.Y99S and p.Y99N) and one known variant (p.L151F).

To date, 19 GUCA1A missense and 3 in-frame deletion/insertion variants in heterozygous states have been reported as causes of AD-MD and AD-COD/CORD in HGMD Professional (2019.3)14,15,16,17,18,20,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Most reported variants (18/22, 81.8%) were concentrated within or around EF-hand domains 3 and 4, which are essential for cytosolic Ca2+/Mg2+ binding4,5,6. Amino acid residues Y99 and L151 are also located on EF-hand 3 helix E and EF-hand 4 loop, respectively (Fig. 1C). Regarding the two novel variants (p.Y99S and p.Y99N), a different variant (p.Y99C) at the same position has been reported as “pathogenic” and leads to COD/CORD14,34. The variant p.L151F has also been reported as a cause of CORD16,19. In contrast, the other five variants (p.E17VfsX22, p.F42I, p.D68E, p.L80I, and p.Q184R) identified in the present study, which resulted in “uncertain significance” in the ACMG criteria, did not co-segregate with the disease. Previously, only five missense variants (p.L50I, p.L84F, p.G86R, p.E89K, and p.L176F) located outside EF-hand domains 3 and 4 have been reported as “pathogenic”,14,15,18,23,33 and one variant (p.L50I) has been concluded as “non-pathogenic” by subsequent studies25,35. Experimental studies have clarified that most GUCA1A variants within or around EF-hand domains 3 and 4 lead to the constitutive activation of RetGC by mechanisms of either a dominant-negative effect or gain of function, not haploinsufficiency9,19,23,27,30,31,36. While, recent studies have also demonstrated that the mutated GCAP-1 (p.L84F and p.L176F), located outside EF-hand domains 3 and 4, showed a significantly high affinity for Mg2+ by altered tertiary structure or conformational changes, resulting in stabilizing the RetGC-activating state36,37. Certainly, all reported GUCA1A variants are heterozygous missense or in-frame insertion/deletion variants, but not truncated variants, compatible with the mechanisms of dominant-negative effect/gain of function. Regarding the reported p.Y99C variant34, the mutated GCAP-1 disrupts the N-terminal helix of the helix-loop-helix conformation of the EF-hand domain 3, severely affecting Ca2+ binding at the site9,10. Further, the p.Y99C mutant activates RetGC at low Ca2+ concentration, similar to wild-type GCAP-1, but remains active even at high Ca2+ concentration, when wild-type GCAP-1 normally inhibits the target9,10,13. A similar pathomechanism whereby RetGC activity cannot be suppressed even at high cytosol Ca2+ concentration may be considered to be CORD caused by our novel variants (p.Y99N and p.Y99S). While it is demonstrated that the p.L151F mutant showed decreased Ca2+ affinity and significantly lower thermal stability compared to the wild-type protein38. Among the five non-pathogenic GUCA1A variants identified in this study, p.E17VfsX22, a truncated variant, might be considered to be a haploinsufficiency mechanism, whereas the other four missense variants were located outside EF-hand domains 3 or 4. However, we did not perform any biochemical or biophysical experiment using the four missense mutatns (p.F42I, p.D68E, p.L80I, and p.Q184R). Further, complex pathogenic mechanisms have been reported about mutated GCAP-1 outside EF-hand domains 3 and 418,36,37. Although functional influence by the mutated GCAP-1 was not determined experimentally, all five GUCA1A variants (p.E17VfsX22, p.F42I, p.D68E, p.L80I, and p.Q184R) did not co-segregate with the disease; some family members with the variants were unaffected, concluding that the 5 variants were non-pathogenic.

All reported GUCA1A-associated phenotypes are classified into AD-MD or AD-COD/CORD with progressive macular atrophy14,15,19,23,25,32. In our study, the retinal atrophic areas were apparently more enlarged in older patients. In regard to cone ERG, although previous studies have shown that a variable degree of responses is seen ranging from preserved cone responses in AD-MD to severely decreased cone responses in AD-COD/CORD14,19,23,25,32, all 8 patients examined exhibited severely decreased or non-recordable cone responses (Fig. 3). In contrast, the findings of rod ERG showed a variable degree of responses ranging from nearly normal to non-recordable (Fig. 3), consistent with data from previous studies14,15,19,20,23,24,25,30,31. It is unclear why cone photoreceptors are initially and predominantly affected in GUCA1A-associated COD/CORD. In rod photoreceptors of mice, both GCAP-1 and GCAP-2 (an isoform of GCAP-1) are expressed, whereas GCAP-1 is predominantly expressed in cone photoreceptors39. Thus, GCAP-2 could compensate for dysfunction of GCAP-1 caused by GUCA1A variants in human rod photoreceptors as pointed out previously40. Another possibility is that GCAP-2 reduces an abnormal RetGC activity through competition with mutated GCAP-1 in which wild-type versus mutated GCPA-1 might function at different ratios between cone and rod photoreceptors. Taken together, retinal function gradually deteriorates and leads to COD/CORD in patients with heterozygous pathogenic GUCA1A variants. Clinical features of our 9 patients were consistent with previous studies as CORD with progressive macular atrophy; however, the centrifugal extension pattern of retinal atrophy was different between the families (Fig. 2). Unlike elliptical enlargement of retinal atrophy in families 2 and 3 and previous studies11,12,13, retinal atrophy in family 1 extended over the optic disc and inferior arcade. This unique pattern of retinal atrophy might be a characteristic finding of the p.Y99S variant or be influenced by secondary (genetic or environmental) factors. In addition, the older patient (F1: I-2) with p.Y99S showed non-recordable responses not only in cone ERG but also in rod and combined ERG, and peripheral visual field loss except for the inferior area. To our knowledge, this is the first report of such a case. The clinical course of GUCA1A-associated dystrophies typically exhibits progressive cone dysfunction with macular atrophy, accompanied by later rod dysfunction. Although it is not clarified whether GUCA1A-associated dystrophies ultimately lead to entire loss of rod function in addition to loss of cone function, our finding of patient F1: I-2 suggests that these dystrophies might lead to severe loss of both rod and cone function as the result of continuous progression.

In this study, our cohort of IRDs revealed the prevalence (0.25%, 3/1192 families) of GUCA1A-associated IRDs was lower than that (0.7%, 7/1000 families) of previous large US cohort study21. Our study suggests that GUCA1A-associated IRDs in Japanese population may be rarer compared with US population. In fact, any IRDs associated with GUCA1A variants have never been reported in the Japanese population. Further investigations will need to be undertaken in order to clarify the prevalence of GUCA1A-associated IRDs in each population.

In conclusion, we identified eight rare GUCA1A variants including three pathogenic variants from a large Japanese cohort. Our results indicated that the three pathogenic variants underlie AD-COD/CORD with progressive retinal atrophy, and the prevalence of GUCA1A-associated IRDs may be low among Japanese patients with IRDs.

Patients and Methods

Ethics statement

Institutional Review Boards of the seven participating institutions approved the study protocol [The Jikei University School of Medicine (approval number 24–232 6997); National Hospital Organization Tokyo Medical Center (approval number: R18-029); Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 2010–1067); Mie University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 2429); Teikyo University School of Medicine (approval number: 10-007-4); Iwate Medical University School of Medicine (approval number: HGH23-1); and Kindai University Faculty of Medicine (approval number: 22–132)]. The protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from each participant before participating in this study.

Molecular genetic study

Patients with IRDs were studied from the genotype-phenotype database of the Japan Eye Genetics Consortium (http://www.jegc.org/)41,42. We examined our in-house WES database of 1385 IRD patients and 682 of their family members from 1192 Japanese families. In fact, WES with targeted analysis of the IRD genes listed in the RetNet database (https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/home.htm) was performed.The details of the WES methodology are described elsewhere41,43. We selected patients with IRDs who had rare GUCA1A variants in at least in one allele with a frequency of less than 1% in the Human Genetic Variation Database (http://www.hgvd.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/index.html) and a total frequency of less than 1.0% of the genome Aggregation Database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). Subsequently, the pathogenicity of identified GUCA1A variants was evaluated according to the standards and guidelines of the ACMG44. Lastly, we evaluated the damage to GCAP-1 by using three in silico programs [PolyPhen2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/www/SIFT_seq_submit2.html), and MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/)]. Confirmation and segregation of each GUCA1A variant were performed by Sanger sequencing. Identified GUCA1A variants were compared with the NCBI reference sequence (NM_ 000409.4).

Clinical study

We retrospectively reviewed the detailed medical records of patients with GUCA1A variants, which were determined as pathogenic in genetic analysis. Each patient underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination, including decimal best-corrected visual acuity, funduscopy, fundus autofluorescence imaging (FAF; Spectralis HRA; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany), optical coherence tomography (OCT; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Dublin, CA, USA), and visual field testing using Goldmann perimetry (GP; Haag-Streit, Bern, Switzerland) and/or Humphrey field analyzer (HFA; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG). FF-ERG using a light-emitting diode built-in electrode (LE-4000, Tomey, Nagoya, Japan) was recorded in accordance with the protocols of the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV)45 with the exception of using a stronger flash under dark-adapted (DA) conditions to record a DA 200 (200 cd·s·m−2) ERG. Ganzfeld FF-ERG using Neuropack 2 (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) with corneal contact lens electrodes was recorded according to the ISCEV protocols except for DA 10.0 (10.0 cd·s·m−2) ERG. The detailed procedure and conditions of FF-ERG were previously reported41,46,47,48.

References

Cuenca, N., Lopez, S., Howes, K. & Kolb, H. The localization of guanylyl cyclase-activating proteins in the mammalian retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39, 1243–1250 (1998).

Mendez, A. et al. Role of guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) in setting the flash sensitivity of rod photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98, 9948–9953 (2001).

Pennesi, M. E., Howes, K. A., Baehr, W. & Wu, S. M. Guanylate cyclase-activating protein (GCAP) 1 rescues cone recovery kinetics in GCAP1/GCAP2 knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 6783–6788 (2003).

Palczewski, K. et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of retinal photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase-activating protein. Neuron 13, 395–404 (1994).

Gorczyca, W. A. et al. Guanylyl cyclase activating protein. A calcium-sensitive regulator of phototransduction. J Biol Chem 270, 22029–22036 (1995).

Peshenko, I. V. & Dizhoor, A. M. Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding properties of GCAP-1. Evidence that Mg2+-bound form is the physiological activator of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem 281, 23830–23841 (2006).

Dizhoor, A. M., Lowe, D. G., Olshevskaya, E. V., Laura, R. P. & Hurley, J. B. The human photoreceptor membrane guanylyl cyclase, RetGC, is present in outer segments and is regulated by calcium and a soluble activator. Neuron 12, 1345–1352 (1994).

Lowe, D. G. et al. Cloning and expression of a second photoreceptor-specific membrane retina guanylyl cyclase (RetGC), RetGC-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92, 5535–5539 (1995).

Sokal, I. et al. GCAP1 (Y99C) mutant is constitutively active in autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Mol Cell 2, 129–133 (1998).

Dizhoor, A. M., Boikov, S. G. & Olshevskaya, E. V. Constitutive activation of photoreceptor guanylate cyclase by Y99C mutant of GCAP-1. Possible role in causing human autosomal dominant cone degeneration. J Biol Chem 273, 17311–17314 (1998).

Olshevskaya, E. V. et al. The Y99C mutation in guanylyl cyclase-activating protein 1 increases intracellular Ca2+ and causes photoreceptor degeneration in transgenic mice. J Neurosci 24, 6078–6085 (2004).

Jiang, L. & Baehr, W. GCAP1 mutations associated with autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Adv Exp Med Biol 664, 273–282 (2010).

Behnen, P., Dell’Orco, D. & Koch, K. W. Involvement of the calcium sensor GCAP1 in hereditary cone dystrophies. Biol Chem 391, 631–637 (2010).

Downes, S. M. et al. Autosomal dominant cone and cone-rod dystrophy with mutations in the guanylate cyclase activator 1A gene-encoding guanylate cyclase activating protein-1. Arch Ophthalmol 119, 96–105 (2001).

Kamenarova, K. et al. Novel GUCA1A mutations suggesting possible mechanisms of pathogenesis in cone, cone-rod, and macular dystrophy patients. Biomed Res Int 2013, 517570 (2013).

Jiang, L. et al. Autosomal dominant cone dystrophy caused by a novel mutation in the GCAP1 gene (GUCA1A). Mol Vis 11, 143–151 (2005).

Marino, V. et al. A novel p.(Glu111Val) missense mutation in GUCA1A associated with cone-rod dystrophy leads to impaired calcium sensing and perturbed second messenger homeostasis in photoreceptors. Hum Mol Genet 27, 4204–4217 (2018).

Peshenko, I. V. et al. A G86R mutation in the calcium-sensor protein GCAP1 alters regulation of retinal guanylyl cyclase and causes dominant cone-rod degeneration. J Biol Chem 294, 3476–3488 (2019).

Sokal, I. et al. A novel GCAP1 missense mutation (L151F) in a large family with autosomal dominant cone-rod dystrophy (adCORD). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46, 1124–1132 (2005).

Nong, E., Lee, W., Merriam, J. E., Allikmets, R. & Tsang, S. H. Disease progression in autosomal dominant cone-rod dystrophy caused by a novel mutation (D100G) in the GUCA1A gene. Doc Ophthalmol 128, 59–67 (2014).

Stone, E. M. et al. Clinically Focused Molecular Investigation of 1000 Consecutive Families with Inherited Retinal Disease. Ophthalmology 124, 1314–1331 (2017).

Oishi, M. et al. Next-generation sequencing-based comprehensive molecular analysis of 43 Japanese patients with cone and cone-rod dystrophies. Molecular vision 22, 150–160 (2016).

Kitiratschky, V. B. et al. Mutations in the GUCA1A gene involved in hereditary cone dystrophies impair calcium-mediated regulation of guanylate cyclase. Hum Mutat 30, E782–796 (2009).

Chen, X. et al. GUCA1A mutation causes maculopathy in a five-generation family with a wide spectrum of severity. Genet Med 19, 945–954 (2017).

Manes, G. et al. Cone dystrophy or macular dystrophy associated with novel autosomal dominant GUCA1A mutations. Mol Vis 23, 198–209 (2017).

Huang, L. et al. Molecular genetics of cone-rod dystrophy in Chinese patients: New data from 61 probands and mutation overview of 163 probands. Exp Eye Res 146, 252–258 (2016).

Jiang, L. et al. A novel GCAP1(N104K) mutation in EF-hand 3 (EF3) linked to autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Vision Res 48, 2425–2432 (2008).

Carss, K. J. et al. Comprehensive Rare Variant Analysis via Whole-Genome Sequencing to Determine the Molecular Pathology of Inherited Retinal Disease. Am J Hum Genet 100, 75–90 (2017).

Taylor, R. L. et al. Panel-Based Clinical Genetic Testing in 85 Children with Inherited Retinal Disease. Ophthalmology 124, 985–991 (2017).

Nishiguchi, K. M. et al. A novel mutation (I143NT) in guanylate cyclase-activating protein 1 (GCAP1) associated with autosomal dominant cone degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45, 3863–3870 (2004).

Wilkie, S. E. et al. Identification and functional consequences of a new mutation (E155G) in the gene for GCAP1 that causes autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet 69, 471–480 (2001).

Huang, L. et al. Novel GUCA1A mutation identified in a Chinese family with cone-rod dystrophy. Neurosci Lett 541, 179–183 (2013).

Weisschuh, N. et al. Mutation Detection in Patients with Retinal Dystrophies Using Targeted Next Generation Sequencing. PLoS One 11, e0145951 (2016).

Payne, A. M. et al. A mutation in guanylate cyclase activator 1A (GUCA1A) in an autosomal dominant cone dystrophy pedigree mapping to a new locus on chromosome 6p21.1. Hum Mol Genet 7, 273–277 (1998).

Sokal, I. et al. Ca(2+)-binding proteins in the retina: from discovery to etiology of human disease(1). Biochim Biophys Acta 1498, 233–251 (2000).

Marino, V., Scholten, A., Koch, K. W. & Dell’Orco, D. Two retinal dystrophy-associated missense mutations in GUCA1A with distinct molecular properties result in a similar aberrant regulation of the retinal guanylate cyclase. Hum Mol Genet 24, 6653–6666 (2015).

Vocke, F. et al. Dysfunction of cGMP signalling in photoreceptors by a macular dystrophy-related mutation in the calcium sensor GCAP1. Hum Mol Genet 26, 133–144 (2017).

Dell’Orco, D., Behnen, P., Linse, S. & Koch, K. W. Calcium binding, structural stability and guanylate cyclase activation in GCAP1 variants associated with human cone dystrophy. Cell Mol Life Sci 67, 973–984 (2010).

Schmitz, F. et al. EF hand-mediated Ca- and cGMP-signaling in photoreceptor synaptic terminals. Front Mol Neurosci 5, 26 (2012).

Dell’Orco, D., Sulmann, S., Zagel, P., Marino, V. & Koch, K. W. Impact of cone dystrophy-related mutations in GCAP1 on a kinetic model of phototransduction. Cell Mol Life Sci 71, 3829–3840 (2014).

Fujinami, K. et al. Novel RP1L1 Variants and Genotype-Photoreceptor Microstructural Phenotype Associations in Cohort of Japanese Patients With Occult Macular Dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57, 4837–4846 (2016).

Kameya, S. et al. Phenotypical Characteristics of POC1B-Associated Retinopathy in Japanese Cohort: Cone Dystrophy With Normal Funduscopic Appearance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 60, 3432–3446 (2019).

Katagiri, S. et al. Compound heterozygous splice site variants in the SCLT1 gene highlight an additional candidate locus for Senior-Loken syndrome. Sci Rep 8, 16733 (2018).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17, 405–424 (2015).

McCulloch, D. L. et al. ISCEV Standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update). Doc Ophthalmol 130, 1–12 (2015).

Hayashi, T. et al. Compound heterozygous RDH5 mutations in familial fleck retina with night blindness. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 84, 254–258 (2006).

Katagiri, S. et al. RPE65 Mutations in Two Japanese Families with Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Ophthalmic Genet 37, 161–169 (2016).

Kutsuma, T. et al. Novel biallelic loss-of-function KCNV2 variants in cone dystrophy with supernormal rod responses. Doc Ophthalmol 138, 229–239 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for participation in this study. We thank Ritsuko Nakayama for assistance in genetic analysis. This work was supported by grants from the Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Diseases (17ek0109282h0001 to T.I.) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (17K11434 to T.H.), and Japanese Retinitis Pigmentosa Society (JRPS) Research Grant (to T.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M. and T.M. performed the molecular genetic analyses in 3 families with pathogenic GUCA1A variants. K.Y. and T.I. performed the whole-exome sequencing. K.M., S.K. and T.H. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. K.F., L.Y., T.M. and T.N. assisted with data interpretation. K.K., K.S., S.M., M.K., S.U., H.T. and K.T. performed ophthalmic examination at each institution. T.H. designed and supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mizobuchi, K., Hayashi, T., Katagiri, S. et al. Characterization of GUCA1A-associated dominant cone/cone-rod dystrophy: low prevalence among Japanese patients with inherited retinal dystrophies. Sci Rep 9, 16851 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52660-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52660-1

This article is cited by

-

Clinical characterization of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa with NRL mutation in a three-generation Japanese family

Documenta Ophthalmologica (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.