Abstract

Alcohol increases the risk of both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and colorectal neoplasia. In this hospital-based case-control and retrospective cohort study, we sought to determine whether development of colorectal neoplasia increases the risk of HCC in patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD). In the phase I case-control analysis, the association between history of colorectal cancer (CRC) and HCC development was assessed in patients with ALD by logistic regression modeling (n = 1,659). In the phase II retrospective cohort analysis, the relative risk of HCC development was compared in ALD patients with respect to the history of CRC by a Cox model (n = 1,184). The history of CRC was significantly associated with HCC in the case-control analysis (adjusted odds ratio, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.06–3.15; P < 0.05). ALD patients with CRC had higher risk of developing HCC compared to those without CRC (adjusted hazards ratio [HR], 5.48; 95% CI, 1.63–18.36; P = 0.006) in the cohort analysis. Presence of CRC, liver cirrhosis, elevated baseline alpha-fetoprotein level, and low platelet counts were independent predictors of HCC development in ALD patients. Patients with history of CRC had an increased risk of HCC in both cirrhotic (HR, 3.76; 95% CI, 1.05–13.34, P = 0.041) and non-cirrhotic (HR, 23.46; 95% CI, 2.81–195.83, P = 0.004) ALD patients. In conclusion, ALD patients with CRC are at increased risk of developing HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol-related liver disease is a global health burden that causes 348,000 deaths and 10,997,000 disability-adjusted life years annually1. Alcohol causes a spectrum of liver diseases comprising simple steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)2,3. Alcohol is the second most important risk factor for HCC, following viral hepatitis4, and alcohol-related HCC deaths have not significantly decreased over the last decade5. Early detection is critical to improve the prognosis of HCC, but no effective strategies have been established for the early diagnosis of HCC in patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD)4,6,7. Cirrhosis is one of the most important predictors for alcohol-related HCC, along with old age, comorbid chronic viral hepatitis, and the amount of alcohol consumption8,9,10. However, even patients with alcoholic cirrhosis have relatively lower risk of developing HCC compared to those with viral hepatitis-associated cirrhosis11,12,13. Therefore, further refined risk stratification is prerequisite for the development of a cost-effective HCC surveillance strategy in patients with ALD.

Alcohol is a risk factor not only for HCC but also for colorectal neoplasm: excessive alcohol consumption increases the likelihood of developing adenomas and colorectal cancer (CRC)14,15,16,17. Chronic ethanol consumption usually promotes carcinogenesis by production of toxic acetaldehyde, induction of cytochrome P450 2E1 that causes oxidative stress and procarcinogen activation, and provocation of global DNA hypomethylation18. Since these carcinogenic pathways are known to contribute to the development of both colorectal neoplasm and HCC10,19,20, we hypothesized that ALD patients who develop colorectal neoplasm are at risk of further developing HCC. The aim of this study was to elucidate the relationship between the presence of colorectal neoplasm and the subsequent risk of HCC in patients with ALD.

Methods

Data sources

We recruited ALD patients from two university-affiliated, tertiary referral centers in South Korea. Patients with ALD were identified from the electronic health record of the centers21,22 by the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10) code of K70. The diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease was made by four hepatologists (WK, ESJ, SHJ and JWK) by documentation of alcoholic excess and evidence of liver disease23. Alcohol consumption amount was assessed via the hepatologists’ interview with patients and their family members. Diagnosis of fatty liver was made radiologically24, and liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by liver biopsy, radiological findings or presence of esophageal varix25. Clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki26, and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the current study and anonymous analysis of the data. The institutional review board approved this study (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital IRB; IRB no. B-1703/388-108).

Study design

This study consists of two-phase investigations: phase I case-control analysis and phase II retrospective cohort analysis (Fig. 1). The case-control analysis aimed to investigate the possible association between history of CRC and HCC risk in ALD patients, whereas the cohort analysis sought to determine the relative risk of HCC in ALD patients with the history of colorectal adenoma (CRA) or CRC.

Phase I case-control analysis

In the phase I single-center case-control analysis, we selected 1,659 ALD patients who received imaging work-up for HCC, i.e., liver ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between April, 2003 and April, 2018. Patients with evidence of other chronic liver disease such as hepatitis B or C virus infection, hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, primary biliary cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis were excluded. Decompensated patients with Child-Pugh class C were also excluded from analysis.

ALD patients diagnosed with HCC were selected as cases, and those without any evidence of HCC were selected as controls. The index date was defined as the date of HCC diagnosis for cases, and the date of initial imaging work-up for controls. The history of CRC was coded positive if a patient had received surgical treatment for CRC or if colonoscopic examination(s), performed as described below, revealed colorectal adenocarcinoma before the index date.

Phase II cohort analysis

In the phase II retrospective cohort analysis, an ALD cohort was electronically formed by assembling ALD patients who received imaging work-up for HCC and colonoscopic examination(s) from the two centers. The cohort was composed of a subgroup of the phase I controls and a separate cohort formed at Boramae Medical Center. Patients with evidence of other chronic liver disease were excluded in the same way as the phase I cohort, and the following additional exclusion criteria were applied: patients were excluded if HCC was detected at initial screening or within 6 months after initial screening or if follow-up data was incomplete. The observation starting point for the longitudinal cohort analysis was the time of colonoscopic examination(s). During follow-up, patients underwent additional liver US with or without alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels. Follow-up US at 6 months of interval was recommended for patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis, and follow-up US was performed at the discretion of attending hepatologists for patients without evidence of liver cirrhosis. Dynamic CT or MRI was performed if serum AFP levels or surveillance US indicated a need for further evaluation according to the recall policies27,28. Liver biopsy was performed if CT or MRI showed new hepatic nodule(s) which did not show typical enhancement pattern diagnostic of HCC. The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of HCC, which was diagnosed based on histological or radiological findings29.

CRC screening in the study population

CRC is the third most common cancer in Korea30, and Korean National Cancer Screening Programme has implemented programmatic CRC screening by means of fecal occult blood tests for all Koreans aged ≥ 50 years since 200431. If the fecal occult blood test is positive, colonoscopy or double-contrast barium enema has been provided. Colonoscopy has also been recommended for CRC screening regardless of the occult blood test result in average-risk asymptomatic adults according to clinicians’ discretion and recipients’ preference32. In our cohorts, colonoscopic CRC screening was performed either on the programmatic basis following the Korean guideline or on the opportunistic basis. If colonoscopic examinations were performed more than once, the highest grade of colonic pathology was determined and the earliest date of examination was chosen as the ultimate grade of pathology.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and R version 3.4.2 (http://www.cran.r-project.org/). Wilcoxon rank sum test or one-way ANOVA test were used for continuous variables, and chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. In phase I case-control analysis, the odds ratios (ORs) for HCC were calculated by logistic regression analysis. In phase II cohort analysis, the cumulative incidence of HCC was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the hazard ratios (HRs) for HCC were derived by a Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Phase I case-control analysis: association between the history of CRC and the risk of HCC in patients with ALD

The case-control analysis compared 445 ALD-related HCC cases and 1,214 ALD controls without HCC with respect to the history of CRC. Of the 445 HCC patients, 24 had history of CRC, among whom 7 HCC was confirmed pathologically. HCC patients showed older age, higher proportion of female sex, higher smoking rate and drinking amount, higher probability of the history of CRC (5.4% vs. 2.7%; p = 0.008) (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis showed that past history of CRC was significantly associated with future development of HCC (unadjusted OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.19–3.49; P < 0.001), along with sex, drinking amount and smoking as additional significant variables associated with HCC development (Table 2). The association of CRC history with HCC remained significant after adjustment for confounders (adjusted OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.06–3.15; P < 0.05), indicating possible association between development of CRC and HCC in ALD.

Phase II cohort analysis: presence of CRC as an independent predictor of future HCC development in ALD

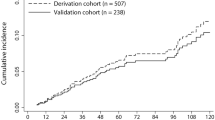

A total of 1,263 patients were assembled for the longitudinal cohort. After excluding 79 patients with incomplete follow-up information, 1,184 patients were finally selected for the cohort analysis (Fig. 1). CRA and CRC were present in 46% and 2% of ALD cohort, respectively, at the baseline screening colonoscopic examination (Table 3). One-third of CRC patients were diagnosed at the stage of carcinoma in situ (Tis, n = 8/24). Patients with CRC showed higher age, higher proportion of cirrhosis with worse hepatic reserve, higher frequency of smoking and greater amount of alcohol consumption.

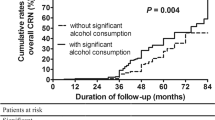

During the median follow-up of 55 months (interquartile range [IQR] = 60, 72,117 person-years), 24 patients developed HCC with the incidence of 33.3/100,000 person-years (95% CI, 22.3–49.7). Among the 24 patients, 4 had history of CRC and HCC was pathologically confirmed in all 4 patients. When the cumulative HCC incidences were compared according to colonic pathologic findings, patients with CRC showed significantly higher probability of further developing HCC compared to patients without colonic neoplasia or patients with CRA (Fig. 2). The median (IQR) size of HCC was not significantly different between patients with and without preceding CRC: 2.7 (5.6) cm vs. 1.9 (3.8) cm for patients with vs. without preceding CRC, respectively (P = 0.312 by Wilcox rank sum test).

Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that patients with CRC had higher risk of developing HCC compared to those without CRC (HR, 12.64; 95% CI, 4. 28–37.15; P < 0.001). CRA was not significantly associated with the risk of HCC development (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.38–2.21; P = 0.851) (Table 4). Other significant baseline risk factors for HCC development included old age, presence of liver cirrhosis, high in alcohol consumption amount, high AFP level, low albumin level, prolonged prothrombin time, and low platelet counts. CRC remained as an independent predictor of HCC development in multivariate analysis (HR, 5.48; 95% CI, 1.63–18.36; P = 0.006), along with liver cirrhosis (HR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.22–8.63; P = 0.018), AFP level > 10 ng/mL (HR, 4.26; 95% CI, 1.41–12.85; P = 0.010), and platelet count < 125×109/L (HR, 5.76; 95% CI, 2.19–15.11; P < 0.001). Patients with any of the risk factors had significantly higher incidence of HCC compared to patients without risk factor (HR, 40.60; 95% CI, 9.53–172.93; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). History of CRC increased the HCC risk regardless of cirrhosis: the HR for HCC was 3.76 (95% CI, 1.05–13.34, P = 0.041) and 23.46 (95% CI, 2.81–195.83, P = 0.004) for ALD patients with or without liver cirrhosis, respectively.

Discussion

Our study found that the risk of subsequent HCC development increased when CRCs were detected in patients with ALD. The initial case-control analysis revealed higher proportion of the prior history of CRC in HCC, suggesting association between the development of CRC and HCC in ALD. The Phase I case-control design cannot confirm the causal relationship, but Phase II longitudinal cohort analysis also demonstrated increased OR of HCC by the history of CRC. Taken together, we believe that the Phase I and II analyses indicate a significant association between the history of CRC and the risk of HCC. Several risk factors for HCC have been established in ALD8,10, but CRC has not been recognized as one yet. The association between CRC and subsequent HCC remained significant after adjusting for known covariates for HCC, indicating that presence of CRC has additional predictive power.

We did not include presence/absence of cirrhosis in Phase I logistic model because not all patients underwent histologic examinations or endoscopic varix study. Since thrombocytopenia is one of the clinical diagnostic criteria of cirrhosis, we believe that the significant difference in platelet counts in Phase I analysis indicate significant association of liver cirrhosis with development of HCC in ALD. Similarly, low albumin levels and platelet counts in the CRC group may be explained by the higher prevalence of liver cirrhosis in Phase II analysis (Table 3). However, detection of CRC remained significant in the multivariate Cox model (Table 4), indicating that CRC history may be an independent risk factor for further HCC irrespective of liver cirrhosis.

Our study did not provide mechanistic explanation of the association between HCC and preceding CRC. We speculate that presence of CRC may indicate either exposure to alcohol exceeding a certain threshold level, or increased host susceptibility to alcohol for malignancies for the following findings. First, the carcinogenic effect of alcohol and/or aldehyde metabolites on colonic mucosa might also contribute to the carcinogenesis of HCC10,19,20. Second, alcohol-induced changes in gut microbiota increase acetaldehyde production33,34, which is a common inducer of both cancers. Moreover, alcohol-induced dysbiosis increases the level of deoxycholic acid (DCA), a gut bacterial metabolite known as a hepatocarcinogen by inducing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype in hepatic stellate cells35. Colonic neoplasia as well as alcohol intake may enhance intestinal permeability and enterohepatic circulation of DCA, which in turn facilitate the development of HCC. Epigenetic36 or immunologic37 alterations by alcohol may also contribute to the pathogenesis of both CRC and HCC.

If alcohol have already caused significant genetic and epigenetic alterations in the liver of ALD patients with CRC, then the diagnosis of CRC may be regarded as a surrogate marker for the risk of developing subsequent HCC in ALD. It can be argued that ALD patients who developed CRC might receive more frequent imaging studies, resulting in an increased chance of HCC detection (lead-time bias). If this is the case, then HCC stages may be less advanced in ALD patients with CRC compared to patients who developed HCC without preceding CRC, which is not the case in our data: the size of HCC was not significantly different between patients with and without CRC. Further studies will be needed, however, to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the association between CRC and HCC in ALD.

Liver cirrhosis38, elevated baseline AFP level39 and low platelet counts25,40 have been reported as significant predictors of HCC in ALD, and our data are line with previous reports. Alcohol intake amount was associated with the risk of HCC in phase I case-control analysis and univariate cohort study, but it was not an independent predictor of HCC in multivariate cohort analysis, probability due to multicollinearity with CRC (Table 3).

HCC surveillance has not been routinely recommended for patients with ALD, due to the widely variable range of its risk and relatively lower contribution of HCC to the mortality of alcoholic hepatitis and/or cirrhosis13,41. Our cohorts also showed relatively low incidence of HCC (33/100,000 person-years), which is consistent with the previous reports38. In contrast, diagnosis of CRC increased the risk of developing HCC by more than 12 folds in univariate analysis. Although CRC develops infrequently in patients with ALD, we suppose that HCC surveillance should be considered when CRC, even with early-stage, is detected in those with ALD. Since patients with no risk factor may have very low risk of developing HCC (Fig. 3), regular HCC surveillance may not be warranted6, whereas those with CRC, especially with additional risk factor(s), may have significantly higher risk of HCC and regular HCC surveillance may be justified. However, further external validation needs to be conducted to evaluate the clinical utility of our risk stratification and the pragmatic strategy of individualized HCC surveillance in ALD.

We excluded patients with Child-Pugh class C (n = 6; 1 with HCC and 5 without HCC) in Phase I analysis because the history of CRC might be less accurate in this group (limited colonoscopic examinations due to grave hepatic prognosis and/or presence of ascites). However, inclusion of these 6 patients for logistic regression analysis has not changed the results of Table 2 (shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2).

Smoking history had the greatest odds ratio among the predictors in Phase I analysis, but showed insignificant hazard ratio in Phase II Cox analysis. We believe that the number of HCC was larger in Phase I analysis (24 vs. 445), so that type 2 error (beta error) occurred for smoking in Phase II analysis, considering the recent reports supporting the carcinogenic potential of smoking in HCC42,43. Since most CRC patients were smokers (23/24, Table 3), further data would be needed to determine whether non-smokers with CRC pose higher risk for HCC.

Our study has several limitations. First, due to the case-control and retrospective cohort design, biases cannot be completely avoided. We do not suppose that the probability of recall bias may be high, because CRC is not a casual history. We also employed an electronic health record system in order to include every eligible patient without omission21,22,44. Despite these efforts, our findings still need to be externally validated by prospective cohort studies. Second, relatively small number of patients had CRC compared to CRA in our cohort. However, since the CRC history is a significant predictor of HCC regardless of cirrhosis, these patients may need to receive enhanced surveillance for HCC. Again, validation in larger-scale studies is still needed with more CRC cases. Third, our multivariate analyses did not include the stage of fibrosis, which may be a major determinant of HCC risk. Considering the invasiveness of biopsy, however, we believe that our non-invasive risk factors can be applied to ALD patients without histologic data in the real-world practice settings. Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) is useful in estimating the risk of HCC development in patients with chronic viral hepatitis45, and the predictive role of LSM may warrant further validation in patients with ALD45,46,47.

In conclusion, the results of this cross-sectional and cohort study indicate that ALD patients with CRC are more likely to develop HCC than patients without history of CRC. CRC, liver cirrhosis, elevated AFP level, and thrombocytopenia independently predict the risk for HCC in patients with ALD.

Data Availability

Data may be available on request after review of the request by our institutional review boards.

References

Collaborators, G. B. D. R. F. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388, 1659–1724, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 (2016).

Gao, B. & Bataller, R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 141, 1572–1585, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002 (2011).

Shah, V. H. Managing alcoholic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 21, 212–219, https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2015.21.3.212 (2015).

European Association For The Study Of The, L., European Organisation For, R. & Treatment Of, C. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 56, 908–943, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 (2012).

Mortality, G. B. D. & Causes of Death, C. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388, 1459–1544, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 (2016).

Bruix, J., Sherman, M. & Practice Guidelines Committee, A. A. f. t. S. o. L. D. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 42, 1208–1236, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20933 (2005).

Omata, M. et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol Int 11, 317–370, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9 (2017).

Joshi, K., Kohli, A., Manch, R. & Gish, R. Alcoholic Liver Disease: High Risk or Low Risk for Developing Hepatocellular Carcinoma? Clin Liver Dis 20, 563–580, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cld.2016.02.012 (2016).

Kawamura, Y. et al. Effects of Alcohol Consumption on Hepatocarcinogenesis in Japanese Patients With Fatty Liver Disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 14, 597–605, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.019 (2016).

Morgan, T. R., Mandayam, S. & Jamal, M. M. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 127, S87–96 (2004).

Sola, R. et al. Probability of liver cancer and survival in HCV-related or alcoholic-decompensated cirrhosis. A study of 377 patients. Liver international: official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver 26, 62–72, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01181.x (2006).

N’Kontchou, G. et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic or viral C cirrhosis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 4, 1062–1068, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.013 (2006).

Jepsen, P., Ott, P., Andersen, P. K., Sorensen, H. T. & Vilstrup, H. Risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med 156(841–847), W295, https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00004 (2012).

Wang, Y., Duan, H., Yang, H. & Lin, J. A pooled analysis of alcohol intake and colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med 8, 6878–6889 (2015).

Zhu, J. Z. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: alcohol consumption and the risk of colorectal adenoma. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 40, 325–337, https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12841 (2014).

Cho, E. et al. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies. Ann Intern Med 140, 603–613 (2004).

Fedirko, V. et al. Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol 22, 1958–1972, https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq653 (2011).

Purohit, V., Khalsa, J. & Serrano, J. Mechanisms of alcohol-associated cancers: introduction and summary of the symposium. Alcohol 35, 155–160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.05.001 (2005).

Na, H. K. & Lee, J. Y. Molecular Basis of Alcohol-Related Gastric and Colon Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 18, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061116 (2017).

McKillop, I. H. & Schrum, L. W. Alcohol and liver cancer. Alcohol 35, 195–203, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.004 (2005).

Yoo, S. et al. Seoul National University Bundang Hospital’s Electronic System for Total Care. Healthcare informatics research 18, 145–152, https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2012.18.2.145 (2012).

Yoo, S., Kim, S., Lee, K. H., Baek, R. M. & Hwang, H. A study of user requests regarding the fully electronic health record system at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. Stud Health Technol Inform 192, 1015 (2013).

O’Shea, R. S., Dasarathy, S. & McCullough, A. J. Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver, D. & Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of, G. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 51, 307–328, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23258 (2010).

Joseph, A. E., Saverymuttu, S. H., al-Sam, S., Cook, M. G. & Maxwell, J. D. Comparison of liver histology with ultrasonography in assessing diffuse parenchymal liver disease. Clin Radiol 43, 26–31 (1991).

Mancebo, A. et al. Annual incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and identification of risk groups. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 11, 95–101, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2012.09.007 (2013).

World Medical, A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191–2194, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Kokudo, N. et al. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Japan Society of Hepatology 2013 update (3rd JSH-HCC Guidelines). Hepatol Res 45, https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12464 (2015).

Korean Liver Cancer Study, G. & National Cancer Center, K. 2014 KLCSG-NCC Korea Practice Guideline for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut Liver 9, 267–317, https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl14460 (2015).

Bruix, J., Sherman, M. & American Association for the Study of Liver, D. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 53, 1020–1022, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24199 (2011).

Welfare’, M. o. H. a. Korea Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2014 (2016).

Kim, Y., Jun, J. K., Choi, K. S., Lee, H. Y. & Park, E. C. Overview of the National Cancer screening programme and the cancer screening status in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 12, 725–730 (2011).

Lee, B. I. et al. Korean guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and polyp detection. Korean J Gastroenterol 59, 65–84 (2012).

Homann, N., Tillonen, J. & Salaspuro, M. Microbially produced acetaldehyde from ethanol may increase the risk of colon cancer via folate deficiency. Int J Cancer 86, 169–173 (2000).

Malaguarnera, G., Giordano, M., Nunnari, G., Bertino, G. & Malaguarnera, M. Gut microbiota in alcoholic liver disease: pathogenetic role and therapeutic perspectives. World J Gastroenterol 20, 16639–16648, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16639 (2014).

Yoshimoto, S. et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 499, 97–101, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12347 (2013).

Dumitrescu, R. G. Alcohol-Induced Epigenetic Changes in Cancer. Methods Mol Biol 1856, 157–172, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8751-1_9 (2018).

Ben-Eliyahu, S., Page, G. G., Yirmiya, R. & Taylor, A. N. Acute alcohol intoxication suppresses natural killer cell activity and promotes tumor metastasis. Nat Med 2, 457–460 (1996).

Fattovich, G., Stroffolini, T., Zagni, I. & Donato, F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology 127, S35–50 (2004).

Ikeda, K. et al. A multivariate analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinogenesis: a prospective observation of 795 patients with viral and alcoholic cirrhosis. Hepatology 18, 47–53 (1993).

Velazquez, R. F. et al. Prospective analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 37, 520–527, https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50093 (2003).

Jepsen, P. & Ott, P. Hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6, 651–653, https://doi.org/10.1586/egh.12.59 (2012).

Abdel-Rahman, O. et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for the development of and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: An updated systematic review of 81 epidemiological studies. J Evid Based Med 10, 245–254, https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12270 (2017).

Yi, S. W., Choi, J. S., Yi, J. J., Lee, Y. H. & Han, K. J. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma by age, sex, and liver disorder status: A prospective cohort study in Korea. Cancer 124, 2748–2757, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31406 (2018).

Lee, C. S. et al. Liver volume-based prediction model stratifies risks for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients on surveillance. PLoS One 13, e0190261, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190261 (2018).

European Association for Study of, L. & Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del, H. EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: Non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol 63, 237–264, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.006 (2015).

Sultanik, P. et al. The relationship between liver stiffness measurement and outcome in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis: a retrospective longitudinal hospital study. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 44, 505–513, https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13722 (2016).

Mueller, S., Seitz, H. K. & Rausch, V. Non-invasive diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 20, 14626–14641, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14626 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant to J-W Kim, funded by the Korean Government (2013R1A1A2061509). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantor of article: J.W.K. Concept and design: D.J., W.K. and J.W.K.; acquisition of data: D.J., W.K., J.W.K., J.C., D.L., S.J., E.S.J., Y.J.C., H.Y., C.M.S., Y.S.P., S.H.J., N.K. and D.H.L.; statistical analysis and interpretation of data: D.J., W.K. and J.W.K. All authors participated in drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, W., Jeong, D., Chung, J. et al. Development of colorectal cancer predicts increased risk of subsequent hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic liver disease: case-control and cohort study. Sci Rep 9, 3236 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39573-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39573-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.