Abstract

Understanding the role of graphene in the thermal stability and pore morphology of polymer derived silicon oxycarbide is crucial for electrochemical energy storage and hydrogen storage applications. Here in this work, we report the synthesis of graphene nanoplatelets dispersed silicon oxycarbide ceramics by the polymer to ceramic synthesis route. Samples containing graphene and without graphene are subjected to different pyrolysis conditions and are characterized using FT-IR, XPS, Raman spectroscopy, XRD, FE-SEM, HR-TEM, and BET. The results show that the graphene dispersed in the ceramic has undergone structural distortions upon pyrolysis and resulted in the formation of nanoclusters of graphene and turbostratic graphene. The XRD results confirm that with the incorporation of higher wt.% of GNP there is resistance to crystallization even at an exceedingly high pyrolysis temperature. The pores are bimodal in nature with specific surface area ranging between 22 and 70 m2/g and are generated in-situ during the polymer to ceramic conversion. Our study confirms that upon adjusting the graphene content it is possible to tune the structure and pore morphology of the polymer derived ceramics as per the requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years there is an outburst of research in the synthesis and characterization of polymer derived ceramics (PDC) for various functional applications such as in energy storage, lithium-ion batteries, photocatalysis, thermoelectrics and drug delivery1,2,3,4,5,6. For many of these applications, porous PDCs are considered to be advantageous than their dense counterpart. For instance, it was demonstrated by Dibandjo et al. that porous silicon oxycarbide exhibited a better electrochemical response in comparison to its dense counterpart for lithium storage applications7. The porosity in these ceramics is inherently developed during the synthesis and by proper control of the processing parameters, it is possible to tailor the pore morphologies as per the requirements. Recent two review papers published on porous PDCs summarizes the various processing strategies to be adopted for getting the proper microstructure8,9. Among the different pore morphologies, hierarchical porosity seems to have gained the highest attention9,10. In our study, we have adopted a simple method by which tunable hierarchical porosity can be attained through the proper control of the precursor chemistry. However, the usage of these mesoporous ceramics for energy storage applications such as in lithium-ion batteries is limited due to its low electrical conductivity of 3 × 10−9 S/cm11.

In this context, further enhancement of functional properties in PDCs can be achieved by the addition of conductive nano-fillers such as carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide and graphene nanoplatelets (GNP). Recent studies have shown that the addition of nanofillers like multi-walled carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide dispersoids could lead to an enhancement of electrical conductivity by three to four orders of magnitude in these ceramics11,12,13,14,15. In one such study by David et al. graphene oxide – silicon oxycarbide PDC system was explored as a suitable anode material for lithium-ion batteries and has shown considerably high cycling efficiency with remarkable structural stability1. Despite the aforementioned literature, there is no significant work reported so far on the addition of GNP into the silicon oxycarbide and its effect on the structural stability and pore morphology of the PDC. GNP is one to a few atomic layer thick material and can sustain remarkable current densities along with exceptional thermal and mechanical properties16,17. Hence, these GNP can be envisaged as suitable nano-fillers for these ceramics. The present work, therefore, tries to establish the influence of GNP in the polymeric precursor mixture and its effect on the pyrolyzed samples, both in amorphous and crystalline forms. Through this study we have tried to demonstrate the effect of GNP in terms of the different phases in the pyrolyzed ceramic samples, nature of the graphene left after pyrolysis, its impact on the turbostratic graphene in the ceramic and finally, the resulting effect on the pore morphology of the ceramic. This study also tries to reflect on the balance between having a high specific surface area (SSA) and turbostratic graphene content in the ceramic which are essential requirements for any functional application. Moreover, it is expected to give direction towards synthesizing a suitable material for potential electrochemical energy storage applications such as in lithium-ion batteries wherein a right mixture of amorphous and crystalline material with controlled porosity and graphene is expected to yield better results.

Results

Material characterization

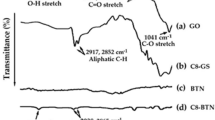

A commercially available GNP was used as the nano-filler and its structure is characterized using Raman spectroscopy and is shown in Fig. 1(a). The intense peaks observed at 1561 cm−1, 2655 cm−1 and 2688 cm−1 corresponds to that of G, 2D1 and 2D2 peaks of GNP and it could be inferred from their intensity ratio (I2D/IG ~ 0.23) that it is a few layered graphene. In addition, the presence of a single sharp D (disorder induced) peak at 1332 cm−1 indicates that the defects are present in the GNP18. In order to establish the structural stability of GNP upon exposure to high temperature, these powders were subjected to heat-treatment at 1500 °C in Ar atmosphere. The Raman spectrum of the heat-treated GNP is shown in the same figure and the peaks closely match with that of the as-received GNP ensuring its structural stability (for details refer to Table 1). However, a peak shift of +1 cm−1 to +4 cm−1 was observed for all the peaks upon heat-treatment and it could be due to the change in the bond length due to the thermal stresses. Moreover, we observe sharpening of the G-peak after heat-treatment at 1500 °C (~9 cm−1). Further, from the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) the absence of peaks corresponding to C-H (2967 cm−1) and Si-CH3 (1268 cm−1) and the presence of Si-O-Si (1100 cm−1) and Si-C (800 cm−1) peaks in the pyrolyzed samples suggests the progress in polymer to ceramic conversion (Fig. 1(b)). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of the 3wt.% GNP dispersed Si-O-C pyrolyzed at 1000 °C revealed the presence of O 1s, C 1s, Si 2s, Si 2p and O 2s peaks (Fig. 1 (c)). The elemental composition at the surface was found to be 39.46 at.% C (27.67 wt.%), 38.20 at.% O (35.69 wt.%) and 22.34 at.% Si (36.64 wt.%). For gaining detailed information on the local environment detailed scans were performed across each of these peaks (O 1s, C 1s and Si 2p). The O/Si atomic ratio of 1.7 is closer to the results given by chemical analysis listed in the literature19. However, the C/Si atomic ratio of 1.76 is relatively high which could be due to the addition of GNP resulting in the local enrichment of the C content. The peaks were deconvoluted and the corresponding fitted peaks are shown in Fig. 1 (d–f). The Si (2p) spectrum shows a peak at 101.94 eV arising due to the formation of the SiO2C2 and at 102.025 eV presence of SiO3C. The presence of both of these peaks confirms the amorphous nature of the ceramic. For the C (1s) spectrum, peaks were observed at 284.28, 286.31, 288.33 eV and are assigned to Si-C (SiC4), C=O, and C-O, respectively. Again, the highest intensity for the Si-C peak indicates towards completion of the pyrolysis process and formation of the silicon oxycarbide. Similarly, for O (1s), the peaks at 531.61, 532.62, 529.28 and 534.94 eV correspond to Si-O, Si-O-Si, C-O, and C=O, respectively.

Structural evolution from polymer to ceramic. (a) Raman spectra of the as-received GNP and the GNP heat-treated at 1500 °C in Ar atmosphere. (b) Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy spectra of Si-O-C after pyrolysis at 1000 °C of the 3 wt.% GNP dispersed polymeric mixture and the crosslinked GNP dispersed polymeric mixture. In the inset, the digital photograph of the pyrolyzed sample is shown and the pores can be seen. (c) XPS spectrum of the 3 wt.% GNP dispersed Si-O-C pyrolyzed at 1000 °C. High-resolution XPS spectrum of the pyrolyzed samples in the (d) C-1s region, (e) Si-2p region and (f) O-1s region. Deconvoluted peaks show the various bonds existing in the Si-O-C ceramic.

Structural Characterization

Similar to GNP, the silicon oxycarbide ceramics with and without GNP pyrolyzed at 1500 °C also have peaks corresponding to D band and G band in their respective Raman spectrum (Fig. 2 (a)). However, it is to be noted that the intensity of the D peak is higher than that of the G peak for all the pyrolyzed samples inferring higher concentration of defects in comparison to GNP (Table 1). This could be associated to two reasons: (i) presence of defects in the form of grain boundaries and distortions in the GNP20 and (ii) presence of defects in the free carbon or turbostratic graphene produced during the polymer to ceramic conversion16. For further understanding, the peaks were deconvoluted (Fig. 2(b)) and the lowest ID/IG of 1.32 was observed for the 6 wt.% GNP modified silicon oxycarbide (Table 1). A lower ID/IG ratio reflects a better ordered graphitic structure with lower defect concentration. In addition, the 2D band (overtone of the D band) and D + G band are also present in the pyrolyzed samples. The presence of these bands and their position is strongly dependent on the structural integrity of the ceramic.

Structural characterization of pyrolyzed ceramic. (a) Raman spectra of Si-O-C PDC without GNP and with 3 wt.% and 6 wt.% GNP pyrolyzed at 1500 °C in Ar atmosphere. (b) Shows the corresponding fitted curve for the Si-O-C PDC with 6 wt.% GNP. (c) XRD of the Si-O-C 3 wt.% GNP pyrolyzed ceramics at 1000 °C, 1250 °C and 1500 °C is shown (d) XRD of the Si-O-C sample pyrolyzed at 1500 °C without GNP and with 3 wt.% and 6 wt.%, GNP is shown. All the plots shown are normalized.

The effect of pyrolysis temperature on the structural evolution of the GNP modified ceramics can be observed from the X-ray diffractogram (XRD) shown in Fig. 2(c). The characteristic peak corresponding to carbon (2θ = 26°) can be observed in the GNP containing samples pyrolyzed at 1000, 1250 and 1500 °C. This could be corroborated with the XRD of the as-received GNP and the GNP heat-treated at 1000 °C (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the peaks related to SiC and SiO2 are not so prominent in the XRD of the 1000 & 1250 °C pyrolyzed samples suggesting the predominant amorphous nature of the ceramic. In Fig. 2(d) the structural evolution of the ceramic modified with various weight fraction of GNP pyrolyzed at 1500 °C is shown. The intensity of the carbon peak seems to increase with an increase in the wt.% of the GNP. Due to phase separation, graphitic domains in the form of free carbon will be created additionally and this in presence of GNP may enhance the formation of further graphitic domains. It has been reported that the presence of graphene in the system tends to lower the crystallization activation energy of free carbon13,15. Further, we can observe a decrease in peak intensity corresponding to SiC peaks for 6 wt.% GNP modified silicon oxycarbide suggesting crystallization is influenced by the presence of higher carbon content in the form of GNP. For these pyrolyzed ceramics the crystallite size of the β-SiC tends to vary from ~16 Ǻ to 19 Ǻ.

High resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM) characterization was carried out to visualize the structure of GNP, free carbon and their distribution in the pyrolyzed sample. The dark areas observed in Fig. 3(a) reflect the thick stacking nanostructure of several graphene layers1. Further, the sample containing GNP with layers folded can be pictured in Fig. 3(b) (shown in red circle) and the folding of these layers results in the development of the Moire’s pattern. The presence of the turbostratic graphene could be observed as straight grid lines (seen within yellow rectangles) in the HR-TEM as seen in Fig. 3(c)21. The arrows in indigo indicate the amorphous silicon oxycarbide matrix and the rectangle in blue (Fig. 3(b)) indicates the boundary between GNP and amorphous silicon oxycarbide.

Shows the HR-TEM images of the SiOC1250 3 wt.% GNP (a) dark and bright regions showing GNP and Si-O-C respectively; (b) separation of the hexagonal graphene structure and amorphous Si-O-C phase is shown and in the inset SAD pattern is given and is a diffused spotted pattern; (c) shows the presence of layered GNP and turbostratic graphene dispersed in an amorphous Si-O-C matrix.

Specific surface area characterization

The porosity in the GNP modified ceramics can be visualized from the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images shown in Fig. 4(a). There seems to be two different size range of pores existing in these ceramics: macro-sized pores and meso-sized pores. The macro-sized pores (>50 nm) are existing as channels (Fig. 4(b)) and meso-sized pores (2 to 50 nm) are observed in the struts of the porous ceramic (Fig. 4(c)). The meso-sized pores are produced due to the escapement of the gases during the pyrolysis which gets combined together as it moves towards the surface resulting in macro-sized pores10. A detailed Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET) study further confirm this. The adsorption and desorption behavior of the samples established through BET is shown in Fig. 5(a,b). All the samples possess the hysteresis loop in the N2 adsorption isotherms inferring the mesoporous nature of the pores. Further, the microporosity is inferred through the coinciding adsorption and desorption curves till P/P0 ratios of 0.4–0.5 and the mesoporosity through the hysteresis curves beyond P/P0 ratios of 0.4–0.5. The results are consistent with the work carried out by Vakifahmetoglu et al.10. Our BET study also indicates an overall decrease in SSA with increase in pyrolysis temperature from 1000 to 1250 °C. However, SSA tend to be higher for the SiOC1500 sample. In case of GNP modified ceramics, SSA seem to decrease with increase in the pyrolysis temperature. In addition, samples containing GNP exhibited higher SSA compared to the samples without GNP at both 1000 °C and 1250 °C. However, the trend does not seem to hold good for the samples pyrolyzed at 1500 °C which have undergone crystallization (Table 2).

SSA and Pore size distribution: Nitrogen sorption isotherms of the samples pyrolyzed showing the hysteresis (Type IV isotherms) (a) at 1000, 1250 and 1500 °C, (b) 1500 °C sample without GNP and 3 wt.% and 6wt.% GNP. (c,d) shows the corresponding Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) analysis exhibiting the pore size distribution in the pyrolyzed samples.

Discussion

The Raman spectroscopy of the GNP reveals a few layered structure as seen in the results section. The G band is due to the bond stretching of sp2 hybridized carbon and the presence of D peak confirms the existence of defects possibly in the form of sp3 hybridized carbon and grain boundaries. However, after dispersing it in the polymeric mixture and subsequent pyrolysis the graphene structure revealed through Raman seems to be different. This could be associated to the presence of nanodomains of free carbon in the pyrolyzed ceramics. It has been reported in the PDC literature that pyrolysis of these C-rich ceramics can result in the formation of nanodomains of free carbon even before the phase separation process gets initiated. This free carbon could be essentially in the form of turbostratic carbon or graphene like sheets22,23. However, we are unable to observe the D and G peaks in the Raman spectrum for the 1000 °C and 1250 °C GNP dispersed pyrolyzed samples due to the presence of the strong background fluorescence of the amorphous ceramic24 [Refer to supplementary Fig. 2 for more details]. The layered carbon nanostructures dispersed in an amorphous silicon oxycarbide matrix can be seen in the HR-TEM images [Fig. 3(a–c)]. For HR-TEM studies the samples pyrolyzed at 1250 °C was chosen so as to have a clear visualization of graphene structure devoid of SiC and SiO2 crystallites. The selected area diffraction (SAD) pattern shown in the inset of Fig. 3(b) indicate a diffused spotted pattern and is attributed to the layered carbon1.

For the 1500 °C pyrolyzed samples significant overlap of the D and G bands along with the broadening of peaks was observed in the Raman spectra. This signifies that though GNP seems to be thermally stable, defects seem to have increased due to thermal distortions. Also, it could be due to the presence of a higher concentration of free carbon or turbostratic graphene domains. The cluster size of the graphene sheets (La) and the point defect separation distance [LD] in the pyrolyzed samples is determined using the equation developed by Cancado et al.25,26 and are given by equations 1 and 2, respectively.

where λ is the excitation wavelength (532 nm) of the laser used in the Raman spectroscopy. The cluster size of the as-received GNP and GNP-1500 are 45 nm and 64 nm respectively. This indicates that ordering has increased due to the heat-treatment process. However, the cluster size of the SiOC1500 is smaller (13–15 nm), inferring the structure of the graphene is inherently different and these could be associated to the presence of free carbon or turbostratic graphene. The presence of these turbostratic graphene layers has been observed in our HR-TEM studies (Fig. 3). Hence, in our system, we have a combination of two different graphene structures: GNP and turbostratic graphene.

In the case of SiOC1500 GNP modified systems, the cluster size is found to remain same (13–15 nm) with increase in GNP weight fraction. Correspondingly, the separation distance between the defects is also found to remain same (~10 nm). A similar trend in the response of cluster size with carbon nano-fiber weight fraction is reported in the work carried out by Mazo et al. in the carbon fiber incorporated SiOC nanocomposites27. Further, these graphene nanoclusters could have reacted with SiO2 and formed additional SiC, thereby resulting in an overall decrease in the intensity of the SiO2 peak at 2θ = 22° (Fig. 3(d))28. This illustrates that there are two mechanisms of SiC formation in the existing system: (i) by phase separation and (ii) the phase separated SiO2 reacting with the existing turbostratic graphene and forming SiC. This suggests that there should be an increase in the intensity of the peak of SiC for 6wt.% GNP modified ceramic. However, we have not observed an increase in the peak intensity for SiC crystallites. We believe that the only way this could have happened is the decrease in the formation of SiC by phase separation, suggesting resistance to crystallization. There are literature reports which suggests that the presence of high volume fraction of carbon can inhibit crystallization and growth of SiC29,30. However, further studies are required to establish this.

The effect of GNP’s on the evolution of pores in these ceramics was studied using BET analysis. From Table 2 it could be inferred that there is an increase in pore size with increase in pyrolysis temperature till 1250 °C. Further upon pyrolysis at 1500 °C the pore size seems to reduce, indicating densification with crystallization. However, the extent of densification in the crystallized samples is decreased with the increase in GNP weight fraction. Hence the sample with 6 wt.% GNP has largest mean pore diameter and minimum SSA. In addition, studies on the pore size distribution was done using BJH analysis. Figure 5c shows the densification of the ceramic upon crystallization with most of pores in the meso-range (2 to 50 nm). Moreover, the effect of weight fraction of GNP on the pore size distribution of crystallized ceramics can be inferred from Fig. 5d. Unlike the 0 and 3 wt.% GNP incorporated system the 6 wt.% GNP ceramic has pores distributed in the macro-regime (>50 nm) correlating with the result observed in the BET analysis.

In Summary

In the present work, various characterization techniques were used to study the effect of GNP on the structural evolution, pore size distribution, and its morphology in the silicon oxycarbide ceramics. The Raman spectroscopy studies coupled with XRD and HR-TEM confirms that there are two types of graphene structures existing in these GNP modified PDCs. Our study suggests that the phase separation and crystallization in these PDCs is hindered at higher weight fractions of GNP. Moreover, the presence of GNP seems to have a different influence on the pore size distribution for the amorphous and crystalline ceramics. In amorphous systems, the presence of GNP resulted in an increase in SSA, whereas the reverse was observed to be true in crystalline PDC. Hence, the present work gives direction towards the synthesis of GNP dispersed PDC materials which can have the appropriate combination of porosity, pore size, SSA and balance of amorphous and crystalline phases as per the requirement.

Methods

Chemicals

To synthesize silicon oxycarbide, three polymeric precursors were chosen: a linear polymethylhydrosiloxane [PHMS, (CH3)3SiO{(CH3)HSiO}nSi(CH3)3, viscosity: 15–40 mPa.s (20 °C), CAS Number 63148-57-2, Sigma Aldrich, USA] for getting the basic structure of ceramic, vinyl terminated polydimethylsiloxane [PDMS,CH2CH{Si(CH)2O}nSi(CH3)2 CHCH2, viscosity:850–1150 mPa.s (25 °C), CAS Number 68083-19-2, Sigma Aldrich, USA] as a sacrificial pore former, cyclic 2,4,6,8-tetramethyl-2,4,6,8 tetravinlycyclotetrasiloxane [TMTVS, C12H28O4Si4, CAS Number 2554-06-05, Sigma Aldrich, USA) with SiC=C moieties] for increasing the crosslinking density. Hydrotalcite [LDH with formula {Mg6Al2(CO3) (OH)16·4H2O}, CAS Number 11097-59-9, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA], was used in the as-received condition for aligning the pores. Platinum (0)-1,3-divinyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethyldisiloxane complex solution in xylene, Pt2%, [O{Si(CH3)2CH=CH2}2 Pt, Sigma Aldrich, USA] was used as the catalyst for the crosslinking reactions. Graphene (CAS NO.: 7782-42-5, United Nanotech Innovations Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, India) with the specific surface area (SSA) of 300 m2/g was taken for dispersing in the polymeric precursor mixture. All materials are used without further purification.

Preparation of graphene dispersed silicon oxycarbide ceramic

For comparative study three compositional combinations were considered, one was taken without the addition of graphene and the other two with graphene nanoplatelets, 3 wt.% and 6wt.%, respectively. For the three compositional combinations, the weights of the precursors were taken as, PHMS (5 g), PDMS (3.75 g) and TMTVS (2.5 g) along with LDH (2.5 g). The detailed synthesis procedure of Si-O-C PDC is as mentioned in31. In all the cases, the blends were put under magnetic stirring for 10 min at 500 rpm for attaining a homogenous mixture of graphene dispersed polymeric precursor. Subsequently, 100 ppm by weight of Pt relative to PHMS was added into the homogenized blends. The blends were further stirred for 30 min at 500 rpm and then were transferred to a ceramic mold. The ceramic mold was then kept on a hot plate maintained at 230 °C for 8 h for crosslinking. Once crosslinking is done, pyrolysis of these samples was carried out at 1000, 1250 and 1500 °C, respectively in a tubular furnace at a heating rate of 4 °C/min in an atmosphere of argon, followed by a dwell time of 1 h.

Instrumentation and Characterization

The completion of polymer to ceramic conversion was established through Fourier transform- infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) (JASCO FT-IR 4200, Japan). The FTIR analysis was carried out on the samples pyrolyzed at 1000 °C. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) capable of depth profiling by Ar etching was carried out using Omicron Nanotechnology (UK) to determine the surface elemental composition and local environment. Raman spectroscopy was carried out using UniRAM micro-Raman mapping system (Japan) with a laser of wavelength 532 nm. Data acquisition was carried out for an exposure time of 30 s. Ferrari and Robertson have suggested an alternate Raman spectrum fitting method using Breit–Wigner–Fano (BWF) profile for G Peak and Lorentzian for D, 2D and D + G Peak. The position of G Peak is shifted in this method and is calculated using equation \({\omega }_{max}={\omega }_{O}+\frac{(FWHM)}{2\,Q}\) where, Q−1 is the BWF coupling coefficient32. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was carried out using Rigaku - Ultima IV (Japan) with Cu: Kα (λ = 0.154 nm) to establish the effect of graphene on the various phases formed in pyrolyzed samples, conformance of the crystallization and effect of graphene on crystallization of the PDC. All the peaks were fitted using Voigt function and the crystallite sizes were determined using the Scherrer equation from the full width half maximum (β). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) was done using JEOL 3010 (USA) with a UHR pole piece operating at an accelerating voltage 300 kV. The samples were pulverized for the HR-TEM analysis. Field emission – Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM) was carried out using FEI ApreoS (USA) at low vacuum mode and 50 Pa pressure. All the samples were polished following the standard metallurgical practice and ultrasonicated before carrying out FE-SEM. The images were taken using a secondary electron detector. Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET, BESORP-mini II, Japan) analysis was used for determining the SSA and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) analysis for the determination of pore size distribution in the pyrolyzed samples. Type IV isotherms are used for the analysis of BJH plots. All the samples were pulverized before the BET and BJH analysis.

References

David, L., Bhandavat, R., Barrera, U. & Singh, G. Silicon oxycarbide glass-graphene composite paper electrode for long-cycle lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 7, 10998 (2016).

Awin, E. W. et al. Novel precursor-derived meso-/macroporous TiO2/SiOC nanocomposites with highly stable anatase nanophase providing visible light photocatalytic activity and superior adsorption of organic dyes. Mater. 11(3), 362 (2018).

Kousaalya, A. B. et al. Polymer-derived silicon oxycarbide ceramics as promising next-generation sustainable thermoelectrics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 10, 2236–2241 (2018).

David, L., Avadavat, R., Barrera, U. & Singh, G. Polymer-derived ceramic functionalized MoS2 composite paper as a stable lithium-ion battery electrode. Sci. Rep. 5, 9792 (2015).

Bhandavat, R. & Singh, G. Improved electrochemical capacity of precursor derived Si(B)CN-carbon nanotube composite as Li-ion battery anode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 4, 5092–5097 (2012).

Vakifahmetoglu, C., Zeydanli, D., Ozalp, V. C., Borsa, B. A. & Soraru, G. D. Hierarchically porous polymer derived ceramics: A promising platform for multidrug delivery systems. Mater. Des. 140, 37–44 (2018).

Dibandjo, P., Graczyk-Zajac, M., Riedel, R., Pradeep, V. S. & Soraru, G. D. Lithium insertion into dense and porous carbon-rich polymer-derived SiOC ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 32, 2495–2503 (2012).

Kumar, B. V. M. & Kim, Y. W. Processing of polysiloxane-derived porous ceramics: A review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 11, 044303 (2010).

Vakifahmetoglu, C., Zeydani, D. & Colombo, P. Porous polymer derived ceramics. Mater. Sci..Eng. R: Rep. 106, 1–30 (2016).

Vakifahmetoglu, C. et al. Gradient-hierarchic-Aligned porosity SiOC Ceramics. Sci. Rep. 7, 41049 (2017).

Moni, P., Wilhelm, M. & Rezwan, K. The influence of carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide sheets on the morphology, porosity, surface characteristics and thermal and electrical properties of polysiloxane derived ceramics. RSC Advan. 7, 37559–37567 (2017).

Yuxi, Y., Xia, F., Huang, Q., Fang, J. & An., L. Electrical conductivity of silicon carbonitride-reduced graphene oxide composites. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 100, 5113–5119 (2017).

Shen, C., Barrios, E. & Zhai, L. Bulk polymer derived ceramic composites of graphene oxide. ACS Omega. 3, 4006–4016 (2018).

Sang, Z. et al. SiOC nanolayers wrapped 3D interconnected graphene sponge as high-performance anodes for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 6, 9064–9073 (2018).

Shen, C. et al. Anisotropic electrical conductivity in polymer derived ceramics induced by graphene aerogels. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5, 11708–11716 (2017).

Giem, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Giem, A. K. Graphene: Status and Prospects. Science. 324, 1530–1534 (2009).

Ferrari, A. C. et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97(18), 187401 (2006).

Soraru, G. D., Andrea, G. D. & Glissenti, A. XPS characterization of gel-derived silicon oxycarbide glasses. Mater. Lett. 27, 1–5 (1996).

Araujo, P. T., Teronnes, M. & Dresselhaus, M. S. Defects and impurities in graphene-like materials. Mater. Today. 15, 98–109 (2012).

Godoy, N. V., Pereira, J. L., Duarte, E. H., Tarley, C. R. T. & Segatelli, M. G. Influence of activated charcoal on the structural and morphological characteristics of ceramic based on silicon oxycarbide (SiOC): A promising approach to obtain a new electrochemical sensing platform. Mater. Chem. Phys. 175, 33–45 (2016).

Mera, G., Navrotsky, A., Sen, S., Kleebe, H. J. & Riedel, R. Polymer-derived SiCN and SiOC ceramics – structure and energetics at the nanoscale. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1, 3826–3836 (2013).

Jiang, T., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Orlovskaya, N. & An, L. Quantitative analysis of free carbon in polymer derived ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 92(10), 2455–2458 (2009).

Mera, G., Riedel, R., Poli, F. & Müller., K. Carbon-rich SiCN ceramics derived from phenyl-containing poly(silylcarbodiimides). J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 29, 2873–2883 (2009).

Cancado, L. G., Takai, K. & Enoki, T. General equation for the determination of the crystallite size La of nanographite by Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 163106 (2006).

Cancado, L. G. et al. Quantifying defects in graphene via Raman spectroscopy at different excitation energies. Nano Lett. 11, 3190–3196 (2011).

Mazo, M. A., Tamayo, A., Caballero, A. C. & Rubio, J. Enhanced electrical and thermal conductivities of silicon oxycarbide containing carbon nanofibers. Carbon. 138, 42–51 (2018).

Kousaalya, A. B., Kumar, R. & Packirisamy, S. Characterization of free carbon in the as-thermolyzed Si–B–C–N ceramic from a polyorganoborosilazane precursor. J. Adv. Ceram. 2(4), 325–332 (2013).

Srinivasan, N., Sujith, R. & Ravi, K. Processing and characterization of polymer precursor derived silicon oxycarbide ceramic foams and composites. J. Adv. Ceram. 2, 318–324 (2013).

Walter., S., Soraru, G. D., Brequel, H. & Enzo, S. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of sol-gel-derived Si–O–C glasses. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 22, 2389–2400 (2002).

Chauhan, P. K., Sujith. R., Parameshwaran, R. & Siva Prasad, A. V. S. Role of polysiloxanes in the synthesis of aligned mesoporous polymer derived ceramics. Ceram. Intern. (Under Review).

Ferrari, A. C. & Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B. 61, 14095–14107 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The work was financially supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (ECR/2016/000525). We also wish to thank and acknowledge Prof. T. Pradeep, Dept. of Chemistry, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai for permitting to use the HR-TEM facility and Dr. Neha Hebalkar, International Advanced Research Centre for Powder Metallurgy and New Materials, Hyderabad for conducting the XPS characterization. We are thankful to Central Analytical Laboratory at BITS Pilani, Hyderabad Campus for providing access to the characterization facilities such as XRD, FTIR, FE-SEM, and BET. We also acknowledge Prof. Amit Nag, Dept. of Chemistry, BITS Pilani Hyderabad Campus for providing access to the Raman spectroscopy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S. conceived the idea, analyzed the results and wrote part of the manuscript, P.K.C. contributed to the synthesis and characterization of graphene dispersed silicon oxycarbide ceramics, analyzed the results and wrote part of the manuscript. J.G. conducted characterization of Raman, XPS, and FE-SEM and analyzed the results. A.M. is involved in the Raman characterization and writing part of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sujith, R., Chauhan, P.K., Gangadhar, J. et al. Graphene nanoplatelets as nanofillers in mesoporous silicon oxycarbide polymer derived ceramics. Sci Rep 8, 17633 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36080-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36080-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A comparative study of nano-fillers to improve toughness and modulus of polymer-derived ceramics

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.