Abstract

Iron and steels are extensively used as structural materials, and have three primary phase structures: Body-centered cubic (bcc), face-centered cubic (fcc), and hexagonal closed-packed (hcp). Controlling phase stabilities, especially by the use of interstitials, is a universal method that provides a diverse variety of functional and mechanical properties in steels. In this context, hydrogen, which can act as an interstitial species in steels, has been recognized to promote phase transformation from fcc to hcp. However, we here report a dramatic effect of interstitial hydrogen that suppresses this hcp phase transformation. More specifically, the fraction of hcp phase that forms during cooling decreases with increasing diffusible hydrogen content. This new finding opens new venues for thermodynamics-based microstructure design and for development of robust, strong, and ductile steels in hydrogen-related infrastructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen is a key resource for next-generation green energies1, which creates new demands of hydrogen-compatible infrastructures. A challenge to develop such hydrogen-related infrastructures is the significant effect of hydrogen on mechanical degradation of materials2. Specifically, the effect of hydrogen in structural steel components causes deterioration of ductility, delayed fracture, and acceleration of fatigue crack growth, all of which are critical problems requiring solutions to realize a hydrogen-energy based-society. Hydrogen-induced mechanical degradation stems from multiple factors such as hydrogen diffusivity/segregation3, cohesive energy4, number of vacancies5, dislocation mobility6, crack tip deformability7, and phase stability of fcc structures8,9,10. In particular, phase stability has been recognized as a critical factor, because it causes a diffusionless transformation at ambient temperature to bcc or hcp structures. This in turn causes significant changes to hydrogen-related factors such as hydrogen diffusivity11. Moreover, solute hydrogen significantly affects the phase stability of fcc12, and thus, the synergetic effect of hydrogen and phase stability dramatically alters susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement13,14.

From a viewpoint of phase stability, the diffusionless transformation from fcc to hcp is key to understanding the hydrogen-related phase transformation. More specifically, the hcp phase acts as metastable state of bcc, or in other words, the relative phase stability of fcc compared to hcp affects not only hcp transformation but also bcc transformation in fcc steels15,16. In this context, the effect of solute hydrogen on the phase stability of the fcc to hcp has been experimentally investigated for a half-century, and all such experimental studies have indicated that hydrogen promotes hcp transformation12,17,18,19,20,21. A possible reason for this is reported to be a reduction in the stacking fault energy17,20,21. However, in this study, we unexpectedly in contrast found that solute hydrogen in fact distinctly suppresses the hcp diffusionless transformation. This finding rewrites our basic understanding of the hydrogen effect on phase stability of fcc steels, and renovates alloy design strategy for hydrogen-resistant steels. Here we present X-ray diffraction (XRD)-based evidence on this phenomenon, along with a reliable quantification of hydrogen contents.

For this study, we selected a solution-treated Fe-15Mn-10Cr-8Ni (mass%) alloy22 for the following four reasons: (1) The initial constituent phase should be fully fcc at room temperature (RT). (2) The estimated Néel temperature should be near or lower than the starting temperature for the hcp diffusionless transformation23,24 to avoid magnetic transition effects which can counteract the hcp transformation24. (3) The hcp → bcc transformation should not occur after the fcc → hcp transformation. (4) Mobile interstitial elements should not be included to simplify the motion of interstitial hydrogen atoms at ambient temperature. The Fe-15Mn-10Cr-8Ni alloy satisfies these requirements; in particular, the starting temperatures for the hcp diffusionless transformation (Ms) and its reverse (As) are 244 and 336 K, respectively25.

Results

Suppression of hcp transformation by hydrogen uptake

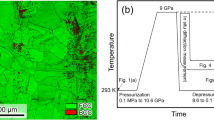

Firstly, we present results of in situ cryogenic XRD measurements, following the cooling pattern shown schematically in Fig. 1(a). As shown in Fig. 1(b), the alloy shows a thermally-induced hcp transformation, with the hcp content increasing with decreasing temperature. It is noteworthy that the hydrogen uptake at RT tends to somewhat prevent formation of the hcp phase, comparing the uncharged sample with that in Fig. 1(c). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 1(d), the specimen with the higher hydrogen content more distinctly exhibits a clear suppression of the thermally induced hcp transformation. Figure 2 summarizes the temperature dependence of the hcp phase fraction present for different hydrogen charging conditions. The pre-existing hcp phase in the specimen hydrogen-charged at RT arises from hydrogen-induced stress occurring during hydrogen charging. Since the temperature of 353 K is higher than the equilibrium temperature of the fcc-hcp transition, no transformation occurs during the hydrogen charging at 353 K. Therefore, below 253 K, the hcp phase fractions decrease with increasing diffusible hydrogen content, irrespective of hydrogen charging temperature. For further clarification, Table 1 shows the diffusible hydrogen content and hcp phase fraction after immersion of the specimens with different hydrogen charging conditions in liquid nitrogen (77 K). It also shows that the hcp phase fraction decreases with increasing diffusible hydrogen content.

Recovery of hcp transformability with hydrogen desorption

Figure 3 shows additional data that support the suppression of hcp transformation. In this set of experiments, the final hydrogen content was controlled by hydrogen desorption via aging at RT, as shown schematically in Fig. 3(a). Here, we performed cyclic aging and cooling treatments to demonstrate the variation in the hcp phase fraction for a single specimen. As expected, the peak intensity corresponding to the hcp phase increases with aging time at RT, Fig. 3(b). Although the global hydrogen content did not significantly change with aging time, the surface lattice expansion attributed to hydrogen decreases as shown in Fig. 4(a). In other words, the decrease in lattice expansion indicates that surface hydrogen is desorbed to a significant extent with aging time. In Fig. 4(b), note that the hcp phase fraction increases with a decrease in the lattice expansion, indicating that the hcp transformation occurs with decreasing surface hydrogen content. Moreover, in order to avoid the cyclic cooling-heating effect, an XRD measurement was also performed after aging for 1 week at 318 K in vacuum without the cyclic process (Fig. 5(a)). Figure 5(b) shows a significant desorption of hydrogen even at the aging time of 34 hours, correspondingly, the XRD profiles shown in Fig. 5(c) indicate recovery of hcp transformability with hydrogen desorption. These facts, taken as a whole, are clear evidence in this study that hydrogen suppresses the hcp transformation in fcc steels.

Increase in friction stress: hydrogen effects on yield strength and reverse transformation temperature

Diffusionless transformation requires dislocation motion26; hence, we must consider a shear stress to drive the dislocations. If hydrogen suppresses hcp transformation via increasing the required shear stress, the effect manifests as an increase in the macroscopic yield strength of the fcc phase. Table 2 shows 0.2% proof stress at 293 K, which generally corresponds to the yield strength. The 0.2% proof stress increased with the hydrogen uptake. Moreover, we note the transformation temperatures with and without hydrogen. The critical transformation temperatures to initiate the forward and reverse diffusionless transformations and their gap are crucial to discuss the hydrogen effect on hcp transformation in terms of thermodynamics and dislocation mechanics. Ms decreases by hydrogen charging at 353 K, as indicated in Fig. 2. As increases by the hydrogen uptake, as shown in Table 2. Thus, hydrogen increases the gap between Ms and As.

Discussion

The in situ XRD measurements clearly demonstrate that hydrogen suppresses hcp transformation, which is unexpected behavior compared to that predicted from previous studies. Here we first discuss why these previous studies showed promotion of hcp transformation by hydrogen, raising three points to explain the contradiction. These are in-turn hydrogen-gradient-induced stress, suppression of bcc phase formation, and lastly strain-induced phase nucleation. Regarding the first, hydrogen causes stress during the charging process before the hydrogen distribution attains a homogeneous distribution27,28. Therefore, a stress-induced hcp transformation occurs when the hydrogen charging temperature is below the highest temperature for deformation-induced diffusionless transformation27,28, as in the case of RT hydrogen charging in the present study. The second point of bcc suppression is related to the fact that bcc transformation occurs via hcp transformation in typical fcc steels such as type 304 stainless steel. Hydrogen has been reported to suppress formation of this bcc phase29, and thus, even if hydrogen does not actually promote hcp transformation, the suppression of the bcc phase can apparently increase the hcp phase fraction. Finally, deformation-induced diffusionless transformations can occur by different mechanisms when dislocation re-structuring induces new nuclei16. Therefore, a deformation-induced hcp transformation may show different behavior from simple thermally induced hcp transformations. Due to these three reasons, we believe the previous studies could not demonstrate the underlying effect of hydrogen on hcp transformation observed here.

From a viewpoint of mechanism, variations in the friction stress, free energy change, and interfacial energy can affect the behavior of hcp diffusionless transformation. The critical condition for hcp diffusionless transformation has been proposed as follows26.

where terms on the left and right sides express the thermal driving force and friction stress acting on the transformation dislocation motion at Ms, respectively. In the equation, n is the atomic plane in thickness, ρ is the molar surface density along {111}, ΔGfcc→hcp is the free energy change by the transformation from fcc to hcp, Estr is the coherency strain energy, and σ(n) is the interfacial energy of fcc/hcp. Based on this equation, hcp diffusionless transformation occurs when the thermal driving force is larger than the friction stress. In particular, the free energy change and friction stress are key to understanding the hydrogen effect that suppresses the hcp diffusionless transformation.

In terms of friction stress, hydrogen increased the yield strength, as indicated in Table 2. Furthermore, hydrogen increased the gap between Ms and As, which also implies an increase in the friction stress by hydrogen. These facts indicate that the friction stress for dislocation motion increases by hydrogen. Figure 6(a) schematically shows this hydrogen effect on the friction stress. Hence, a significant factor suppressing the hcp diffusionless transformation is the hydrogen-enhanced friction stress acting on dislocations. However, only the effect of friction stress cannot explain why the transformation rate during cooling of the specimen charged at 353 K is markedly lower than that of the uncharged specimen. In other words, the decrease in hcp transformation rate implies that hydrogen decreases ΔGfcc→hcp below Ms. In a previous study30, an ab-initio calculation indicated that hydrogen can suppress hcp transformation when the hydrogen content reaches 50 at.%. The 50 at.% hydrogen is unrealistic; however, segregation at finite tilt boundaries or stacking fault, which acts as a nucleation site of hcp formation31, may locally realize the high concentration of hydrogen. Furthermore, the magnetic transition to antiferromagnatism prevents to increase ΔGfcc→hcp with decreasing temperature23,24, and Néel temperature of the present alloy is just below Ms as shown in Table 2. The combined effect of the magnetic transition and hydrogen can significantly reduce an increasing rate of ΔGfcc→hcp with decreasing temperature as schematically shown in Fig. 6(b). In summary, the dual effect of hydrogen on the friction stress and free energy suppresses the hcp diffusionless transformation.

Methods

Sample preparation

An ingot of the Fe-15Mn-10Cr-8Ni alloy was prepared by vacuum induction melting. The specimen was hot-forged and rolled at 1273 K. The bar was solution-treated at 1273 K and subsequently water-quenched. All specimens were cut by spark machining. All specimens were mechanically polished, followed by electrochemical polishing for final finish.

Hydrogen charging and measurement of hydrogen content

In this study, diffusible hydrogen was assumed to play a key role on the diffusionless transformation, as it is trapped at interstitial sites, vacancies, dislocations, and grain boundaries that act as nucleation sites of the transformation. The specimens were cathodically charged with hydrogen in a solution of 3%NaCl with a 3 g/l NH4SCN at a current density of 50 A/m2 at RT for 264 h or 353 K fir 168 h. A platinum wire was used as a counter electrode. The hydrogen charging temperatures were selected to be below and above the As temperature of 336 K. Accordingly, hcp phase transformation during hydrogen can be avoided at 353 K. In addition, hydrogen gas charging was carried out at 100 MPa at 473 K for 250 h for the following two purposes: (1) for generalizing the present results in terms of hydrogen charging method, and (2) for obtaining a thick specimen with homogeneous hydrogen distribution for tensile testing. The diffusible hydrogen content was measured by thermal desorption spectroscopy (TDS) with a quadrupole mass spectrometer at a heating rate of 400 K/h. Diffusible hydrogen content was defined as cumulative hydrogen content from RT to 573 K. As shown in Fig. S1, saturated hydrogen contents introduced at RT and 353 K with a specimen thickness of 0.2 mm were achieved after 264 and 168 h, respectively. This indicates that the hydrogen distribution in the present hydrogen charging conditions used was homogeneous. Moreover, hydrogen desorption rate at 318 K in the specimen hydrogen-charged at 353 K was measured by holding the temperature for 34 hours in vacuum using the quadrupole mass spectrometer. The temperature of 318 K is the ambient temperature of the chamber. The time of 34 hours corresponds to the limitation of the machine system. The specimen used for the hydrogen desorption experiment was used for an XRD measurement after continued aging at 318 K for 1 week in the TDS chamber.

XRD measurements

Plate specimens with dimensions of 8 × 8 × 0.2 mm were used for the following XRD measurements. The in situ cryogenic XRD measurements were carried out with a Fe target at an acceleration voltage of 40 kV and current of 20 mA. The scanning rate and sampling interval were set to 1 degree per minute and 0.05 degree, respectively. The samples were cooled by a closed-helium-cycle refrigerator, and kept within ± 0.2 K of the desired temperature by an automatic temperature controller during the measurements. The cooling rate was 5 K/min and the temperatures at each step were held for 10 min before starting the measurements. The ex situ XRD measurements at RT with the aging process were conducted with a Co target at an acceleration voltage of 40 kV and a current of 20 mA. The scanning rate and sampling interval were set to 1 degree per minute and 0.05 degree, respectively. The specimen for the ex situ XRD measurements was cooled by immersing it into liquid nitrogen. The hcp phase fraction was determined by the reference intensity ratio method using integration of (111)fcc and (10-11)hcp diffraction peaks.

Tensile tests

Tensile tests were carried out at 10−4 s−1 at RT with and without hydrogen gas charging. The gauge dimensions of the specimen were 4 mm in width, 0.6 mm in thickness, and 30 mm in length. The thickness of 0.6 mm is 10 time larger than the average grain size, which is sufficient for reducing a specimen size effect. However, cathodic hydrogen charging in the aqueous solution requires an unrealistic time to provide homogeneous distribution of hydrogen in the thick specimen. Therefore, hydrogen was introduced to the tensile specimen by exposure to high-pressure hydrogen gas as mentioned above. The strain was determined by a video extensometer.

DSC measurements

As temperatures were determined by a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) operated at a cooling rate of 20 K·min−1 using 0.2 mm thick specimens with a square of 2 × 2 mm2. The specimen was first cooled from RT to 133 K, and then, heated up to 673 K. As temperature was defined as the intersection of the tangents of the heat flow peak with the extrapolated base line. Since the transformation rates at Ms in the hydrogen-charged specimens were low, the DSC measurement cannot determine Ms temperatures. In addition, the transformation temperature of the specimen hydrogen-charged at RT was not measured because of the presence of the stress-induced hcp phase.

SQUID

In order to measure Néel temperature, magnetic properties were investigated using a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer in the range of 6–300 K. Thermomagnetization measurements were performed at a cooling rate of 2 K/min under a magnetic field of 5000 Oe.

References

Masel, R. Energy technology: hydrogen quick and clean. Nature 442, 521–522 (2006).

Xu, Q. & Zhang, J. Novel Methods for Prevention of Hydrogen Embrittlement in Iron. Scientific Reports 7, 16927 (2017).

Hickel, T. et al. Ab Initio Based Understanding of the Segregation and Diffusion Mechanisms of Hydrogen in Steels. JOM 66, 1399–1405 (2014).

Yamaguchi, M. et al. First-Principles Study on the Grain Boundary Embrittlement of Metals by Solute Segregation: Part II. Metal (Fe, Al, Cu)-Hydrogen (H) Systems. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 42, 330–339 (2011).

Nagumo, M. Hydrogen related failure of steels – a new aspect. Materials Science and Technology 20, 940–950 (2004).

Robertson, I. M. et al. Hydrogen Embrittlement Understood. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B 46, 1085–1103 (2015).

Song, J. & Curtin, W. A. Atomic mechanism and prediction of hydrogen embrittlement in iron. Nature Materials 12, 145–151 (2012).

Eliezer, D., Chakrapani, D. G., Altstetter, C. J. & Pugh, E. N. The influence of austenite stability on the hydrogen embrittlement and stress- corrosion cracking of stainless steel. Metallurgical Transactions A 10, 935–941 (1979).

Zhang, L., Wen, M., Imade, M., Fukuyama, S. & Yokogawa, K. Effect of nickel equivalent on hydrogen gas embrittlement of austenitic stainless steels based on type 316 at low temperatures. Acta Materialia 56, 3414–3421 (2008).

Koyama, M., Okazaki, S., Sawaguchi, T. & Tsuzaki, K. Hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of Fe-Mn binary alloys with high Mn content: effects of stable and metastable ε-martensite, and Mn concentration. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 47, 2656–2673 (2016).

Hirata, K., Iikubo, S., Koyama, M., Tsuzaki, K. & Ohtani, H. First-principles study on hydrogen diffusivity in BCC, FCC, and HCP iron Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A In press https://doi.org/10.1007/s1166 (2018).

Narita, N., Altstetter, C. J. & Birnbaum, H. K. Hydrogen-related phase transformations in austenitic stainless steels. Metallurgical Transactions A 13, 1355–1365 (1982).

Rozenak, P., Robertson, I. M. & Birnbaum, H. K. HVEM studies of the effects of hydrogen on the deformation and fracture of AISI type 316 austenitic stainless steel. Acta Metallurgica et Materialia 38, 2031–2040 (1990).

Teus, S. M., Shyvanyuk, V. N. & Gavriljuk, V. G. Hydrogen-induced γ → ɛ transformation and the role of ɛ-martensite in hydrogen embrittlement of austenitic steels. Materials Science and Engineering: A 497, 290–294 (2008).

Venables, J. A. The martensite transformation in stainless steel. Philosophical Magazine 7, 35–44 (1962).

Olson, G. B. & Cohen, M. A mechanism for the strain-induced nucleation of martensitic transformations. Journal of the Less Common Metals 28, 107–118 (1972).

Holzworth, M. L. & Louthan, M. R. Jr. Hydrogen-Induced Phase Transformations in Type 304L Stainless Steels. Corrosion 24, 110–124 (1968).

Gavriljuk, V. G., Hänninen, H., Tarasenko, A. V., Tereshchenko, A. S. & Ullakko, K. Phase transformations and relaxation phenomena caused by hydrogen in stable austenitic stainless steels. Acta Metallurgica et Materialia 43, 559–568 (1995).

Sugiyama, S. et al. The effect of electrical hydrogen charging on the strength of 316 stainless steel. Journal of Nuclear Materials 283–287, 863–867 (2000).

Inoue, A., Hosoya, Y. & Masumoto, T. Effect of hydrogen on crack propagation behavior and microstructures around cracks in austenitic stainless steels. Tetsu-to-Hagane 64, 769–778 (1978).

Hermida, J. D. & Roviglione, A. Stacking fault energy decrease in austenitic stainless steels induced by hydrogen pairs formation. Scripta Materialia 39, 1145–1149 (1998).

Sawaguchi, T. et al. Designing Fe-Mn-Si alloys with improved low-cycle fatigue lives. Scripta Materialia 99, 49–52 (2015).

Curtze, S. et al. Thermodynamic modeling of the stacking fault energy of austenitic steels. Acta Materialia 59, 1068–1076 (2011).

Sato, A., Chishima, E., Yamaji, Y. & Mori, T. Orientation and composition dependencies of shape memory effect in Fe-Mn-Si alloys. Acta Materialia 32, 539–547 (1984).

Koyama, M. et al. Martensitic transformation-induced hydrogen desorption characterized by utilizing cryogenic thermal desorption spectroscopy during cooling. Scripta Materialia 112, 50–52 (2016).

Olson, G. B. & Cohen, M. A general mechanism of martensitic nucleation: Part III. Kinetics of martensitic nucleation. Metallurgical Transactions A 7, 1976–1915 (1976).

Maulik, P. & Burke, J. Hydrogen induced martensitic transformations in austenitic steels. Scripta Metallurgica 9, 17–22 (1975).

Rozenak, P. Stress Induce Martensitic Transformations in Hydrogen Embrittlement of Austenitic Stainless Steels. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 45, 162–178 (2014).

Macadre, A., Tsuchiyama, T. & Takaki, S. Hydrogen-induced increase in phase stability in metastable austenite of various grain sizes under strain. Journal of Materials Science 52, 3419–3428 (2017).

Movchan, D. N., Shanina, B. D. & Gavrijuk, V. G. Hydrogen effect on thermodynamic stability of γ- and ε-phase in a Fe-Cr-Mn solid solution. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 38, 8471–8477 (2013).

Olson, G. B. & Cohen, M. A general mechanism of martensitic nucleation: Part I. General concepts and the FCC → HCPtransformation. Metallurgical Transactions A7, 1897–1904 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) (grant number: 20100113) under Industry-Academia Collaborative R&D Program and JSPS KAKENHI (JP16H06365 and JP17H04956). We thank Mr. Natsuki Terao and Mr. Kenshiro Ichii at Kyushu University for carrying out the tensile experiment and thermal desorption spectroscopy, respectively, and are grateful to Prof. M. Mitoh at Kyushu Institute of Technology for helpful work on using SQUID in Kyushu Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K., K.T., S.I. designed the research; Y.A., A.M. measured the XRD patterns; M.K., K.H., and Y.A. analyzed the data; M.K. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koyama, M., Hirata, K., Abe, Y. et al. An unconventional hydrogen effect that suppresses thermal formation of the hcp phase in fcc steels. Sci Rep 8, 16136 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34542-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34542-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hydrogenation treatment under several gigapascals assists diffusionless transformation in a face-centered cubic steel

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Hydrogen Enhances Shape Memory Effect of a Ferrous Face-Centered Cubic Alloy

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.