Abstract

Directly separating minor actinides (MA: Am, Cm, etc.) from high level liquid waste (HLLW) containing lanthanides and other fission products is of great significance for the whole nuclear fuel cycle, especially in the aspects of reducing long-term radioactivity and simplifying the post-processing separation process. Herein, a novel silica-based adsorbent Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P was prepared by impregnating Me2-CA-BTP (2,6-bis(5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5,8,9,9-tetramethyl-5,8-methano-1,2,4-benzotriazin-3-yl)pyridine) into porous silica/polymer support particles (SiO2-P) under reduced pressure. It was found Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P exhibited good adsorption selectivity towards 241Am(III) over 152Eu(III) in a wide nitric acid range, acceptable adsorption kinetic, adequate stability against γ irradiation in 1 and 3 M HNO3 solutions, and successfully separated 241Am(III) from simulated 3 M HNO3 HLLW. In sum, considering the good overall performance of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent, it has great application potential for directly separating MA from HLLW, and is expected to establish an advanced simplified MA separation process, which is very meaningful for the development of nuclear energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the development of nuclear energy, spent nuclear fuel in storage has amounted to around 266 000 t of heavy metal (HM) and is accumulating at a rate of around 7000 t HM/year, which has long-term potential radioactivity threats to the environment and must be managed safely and efficiently. Although the industrialized PUREX (Plutonium Uranium Recovery by EXtraction) process based on TBP can recover 99.5% of uranium and plutonium from spent nuclear fuel, the resulting high-level radioactive liquid waste (HLLW) containing most of the fission products (FP) and minor actinides (MA: Am, Cm, etc.) reserves most of the radioactivity, especially the α-emitters MA, which are the main contributors of radiotoxicity after three centuries storage1. Partitioning MA and the other long-lived FP from HLLW and then transmuting them into short-lived or stabile nuclides, which is the so-called Partition and Transmutation strategy (P&T), can reduce the time isolated from the environment from over 20,000 years to 300–500 years2,3,4,5. However, as the content of lanthanides (Ln), which accounts for about 1/3 of the FP, is much higher than that of MA in order of magnitude, and some Ln have large neutron absorption cross sections and are neutron poisons, Ln should be separated from MA before the transmutation step5,6. Considering MA and Ln dominantly exist as trivalent cations in solution with comparable radii and coordination numbers, mutual separation of MA(III) and Ln(III) is very difficult, which requires high selectivity for the separation materials7,8,9,10,11. Moreover, as the acid in HLLW produced by PUREX process was 2–5 M HNO3 and HLLW is highly radioactive with α, β, γ radioactivity, it further requires that the materials used for MA separation shall have good acid and irradiation resistance stability.

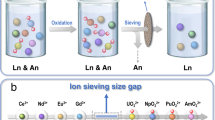

Processes developed over the past decades are mainly based on the co-extraction of MA(III) and Ln(III) from HLLW followed by the An(III)/Ln(III) group separation5,12,13. Firstly, MA and Ln are co-separated from the other FP from high acid (mol/L) HLLW, e.g. the TRPO process using 30% (v/v) mixture of trialkyl phosphine oxides (TRPO) in kerosene14, the TRUEX process using [CMPO] = 0.2 M + [TBP] = 1.4 M in n-dodecane12,15, the DIAMEX process using DMDBTDMA or DMDOHEMA in HTP1,5 and the DIDPA process using 0.5 M DIDPA-0.1 M TBP in n-dodecane16. The oxygen donor ligands, e.g. CMPO, DMDOHEMA, TRPO and DIDPA mentioned above can separate MA(III) and Ln(III) together from fission products in HLLW, but exhibit poor adsorption selectivity between MA(III) and Ln(III). Secondly mutual group separation of MA and Ln are needed, making the integral HLLW separation process very complex. According to the hard and soft acid-base theory, MA(III) and Ln(III) both belong to hard acid, but MA(III) is a little softer than Ln(III) and has better coordination complexation with ligands containing soft coordination atoms N or S17. Using ligands containing N or S is expected to achieve the mutual group separation of MA(III) and Ln(III), e.g. BTP (BTBP) and CYANEX 301 used in SANEX1,18, CYANEX 301 processes19 respectively. Among the various N or S donor ligands, 2,6-bis(5,6-dialkyl-1,2,4-triazin-3-yl)pyridines (BTPs) and 6,6’-bis-(5,6-dialkyl-1,2,4-triazin-3-yl)-2,2’-bipyridines (BTBPs) both exhibit high selectivity for MA(III) over Ln(III) in a wide range of nitric acid solutions (HNO3: 0.1–4 M, M = mol/L) with the separation factor SF Am/Eu around 100 and are considered to be a significant breakthrough in MA separation as before that separation MA could be realized only in low acid (pH range)20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Furthermore, BTPs/BTBPs contain only C, H, N elements and fulfill the CHON principle and thus are completely combustible to gaseous products after use, reducing the second radioactive waste. However, the presently available BTPs used in liquid-liquid extraction suffer from one or more drawbacks, e.g. poor solubility property in traditional solvents (e.g. i-Pr-BTP, CyMe4-BTBP)1,26, slow stability against acid and irradiation (e.g. n-alkylated BTPs and BTBPs)26,27,28, low loading capacity (e.g. CA-BTP)28, and poor back extraction performance (e.g. CyMe4-BTP)26, slow kinetic26 etc. To improve it, We synthesized a new kind of BTP, Me2-CA-BTP (2,6-bis(5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5,8,9,9-tetramethyl-5,8-methano-1,2,4-benzotriazin-3-yl) pyridine) based on the structure of both CyMe4-BTP and CA-BTP avoiding -CH2- group on the α position of the triazine rings which is the weak spot of the ligand under degradation to make it more stable with their chemical structures shown in Fig. 1 26,29,30.

In a word, more challenging processes for directly separating MA from HLLW are eagerly needed to be developed. Separating MA from HLLW by one step process has been proposed, such as 0.2 M CMPO + 1.4 M TBP in n-dodecane used in SETFICS process5, 0.015 M CyMe4-BTBP + TODGA or DMDOHEMA in TPH/Octanol used in the 1-cycle SANEX process5,13, TODGA + water-soluble SO3-Ph-BTBP in TALSPEAK process31. As the processes mentioned above involved more than one kind of extractant, it is inconvenient for the organic phase regeneration. Wei. etc. proposed an compact and effective process based on extraction chromatographic technology named MAREC process (Minor actinide extraction by chromatographic process) as shown in Fig. 1S 32 whose purpose is to directly separate MA(III) from PUREX raffinate HLLW containing fission products Ln and other FPs through single column packed with high-efficiency microporous adsorbent, e.g., BTPs/SiO2-P. If success, it will significantly simplify the MA separation process and is of great significance for the whole nuclear fuel cycle. Efforts to realize the single-column MAREC process from simulated HLLW have been made by using isoHex-BTP/SiO2-P by co-authors33,34, but isoHex-BTP/SiO2-P turned out to be easy to lose the adsorption ability when it accepted γ irradiation in 3 M HNO3 solution in our previous research35, so more advanced materials are needed to be developed. Furthermore, MAREC process uses almost no organic solvent, avoiding the third phase formation and large amount of secondary organic waste accumulation.

In this work, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent was prepared by impregnating 5 g Me2-CA-BTP dissolved in CH2Cl2 into 10 g stable microporous silica/polymer composite support (SiO2-P) particles under reduced pressure. The adsorbent properties of selectivity, kinetics, γ-irradiation stability was studied by batch adsorption experiments. Finally, the feasibility of using Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent to directly separate MA(III) from 3 M HNO3 simulated HLLW through single-column MAREC process was evaluated.

Results

Adsorption selectivity

To study adsorption selectivity, the effects of initial HNO3 concentration (pH = 4–4 M) on Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorption towards 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) were evaluated. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution coefficients (K d) of 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) and the separation factors of 241Am(III) over 152Eu(III) (SF Am/Eu) changing as a function of HNO3 concentration. The distribution factors K d of 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) increased as the HNO3 concentration increased until up to 2 M HNO3 solution which are explained by the adsorption of BTP towards 241Am(III) needing the participation of NO3 − 28. Then with further increase of the acid, the distribution factors K d of 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) decreased. The decreasing distribution factors are explained by metal ions (241Am(III) and 152Eu(III)) and nitric acid competing adsorption for BTP. The whole adsorption mechanism may be as shown in Equation (1) and (2) similar to CA-BTP28. Three NO3 − complexes are incorporated into the coordination sphere so as to maintain neutral due to metal iron’s trivalent oxidation state

.

Overall, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P exhibited good adsorption selectivity towards 241Am(III) with the uptake rate of 241Am(III) over 96% and SF Am/Eu over 75 in a wide nitric acid range of 1–3 M, which was high enough for effective separation 241Am(III) from 152Eu(III). Furthermore, according to previous work29,36, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P showed almost no adsorption ability towards most typical FP except Pd(II) in 3 M HNO3. The results above indicates that Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P has the potential to directly separate MA from high nitric acid (3 M) HLLW. The adsorption ability and the applicable acidity range of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P towards Am(III) has been improved and enlarged compared with CA-BTP which only exhibited good adsorption ability towards Am(III) in 0.5–1 M HNO3 and CyMe4-BTBP whose adsorption ability towards Am(III) increased as HNO3 concentration increased in 0.1–2 M HNO3 and isoHex-BTP which only exhibited good adsorption towards 241Am(III) in ≥ 2 M HNO3 solution28,37,38.

Adsorption kinetics

The effect of contact time on Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorption towards 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) was studied in 1.0 M HNO3 solution at 25 °C with the results shown in Fig. 3. Evidently, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbed 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) quickly reaching almost equilibrium within 0.5 h and exhibited much higher adsorption affinity towards 241Am(III) than 152Eu(III) with SF Am/Eu around 100. Considering the equilibrium time for CA-BTP and CyMe4-BTBP adsorption towards Am(III) was about 10 min and 30 min in solvent extraction27,28, the three systems mentioned above have comparable adsorption kinetic.

Stability evaluation

Considering the radioactive nuclides in HLLW emit vast amounts of radiation, e.g., α, β, γ, the adsorbent irradiation stability is a serious concern in practical applications for HLLW reprocessing. Herein, the stability of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent against γ-irradiation in 1 and 3 M HNO3 solution were evaluated. 0.8 g adsorbent was combined with 40 mL 1 or 3 M HNO3 solution in 50 mL glass vial and irradiated by 60Co-γ source with the absorbed radiation dose rate of 1 kGy·h−1. After being irradiated to the predetermined doses, vacuum filter was used for solid-liquid separation. After drying the Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent in room temperature, the Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent was used to adsorbe 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) in 1 and 3 M HNO3 solution respectively with the results shown in Fig. 4. The K d of 241Am(III) decreased as the absorbed dose increased in both 1 M and 3 M HNO3 solution but was still kept in a high level over 983 and 325 mL/g respectively when the absorbed dose was up to 207 kGy. Meanwhile Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent maintained good adsorption selectivity towards 241Am(III) over 152Eu(III) with SF Am/Eu over 76 and 42 in 1 M and 3 M HNO3 solution respectively in the whole irradiation experiments. Furthermore, considering when isoHex-BTP was irradiated in 3 M HNO3 under the same irradiation conditions, it quickly lost the adsorption ability35, and CyMe4-BTBP distribution factors of 241Am(III) decreased from about 22 to about 12 in 1 M HNO3 when the absorbed γ dose reached 200 kGy with the absorption dose rate of 0.22 kGy/h22, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent exihibted very good γ irradiation stability in 1 M and 3 M HNO3 solution and are expected to directly separate MA from high nitric acid HLLW.

Effect of γ irradiation absorbed dose in (a) 1 M HNO3 (b) 3 M HNO3 on Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorption towards 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) in (a) 1.0 M (b) 3 M HNO3 solution (irradiation conditions: 60Co-γ source, 1 kGy/h, phase ratio: 0.8 g/40 mL; adsorption conditions: phase ratio: 0.1 g/5 mL, Temp.: 25 °C, contact time: 24 h, 241Am(III): 1000 Bq·mL−1 (3.27*10−8 mol/L), 152Eu(III): 1000 Bq·mL−1 (1.02*10−9 mol/L), shaking speed: 120 rpm).

Directly separate MA(III) from HLLW by single-column MAREC process

To examine the separation of MA(III) from fission products, a hot test using simulated 3 M HNO3 HLLW containing typical FP (Sr, Y, Zr, Mo, Ru, Pd, La, Ce, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Dy, 5 mM respectively) and 241Am(III) (500 Bq/mL) was carried out at 35 °C using a glass column (5 mm in inner diameter and 500 mm in length) packed with 5 g Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P with the results shown in Fig. 5 and Table 1. As can be seen, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P showed very poor or almost no adsorption towards lanthanides and most other typical fission products, such as Sr, Y, Zr, Mo, Ru. These elements flowed out with the feed solution in step B and the following 3 M and 0.1 M HNO3 solution in step C and D. On the other hand, Pd, well known as a “soft” metal ion which has strong electron acceptance ability, was adsorbed onto Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P and could not be effectively eluted from the adsorbent by reducing the HNO3 concentration. A complexing agent, thiourea, which has strong complexation affinity with Pd, was attempted to desorb the adsorbed Pd. As shown in Fig. 5, Pd can be effectively eluted off by 0.01 M HNO3–0.1 M thiourea in step E. Meanwhile, 241Am was strongly adsorbed by Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent, then it was eluted off using 0.001 M HNO3-0.01 M DTPA as an eluent with 241Am recovery yield of 95.87% and the other typical fission products less than 3% except Dy. But considering there is almost no Dy or other Ln heavier than Dy in HLLW, the effects caused by Dy are almost negligible. In a word, a successful separation between Am and the various typical fission products including lanthanides has been achieved, which is an important step toward a simplified direct process for separation MA from HLLW.

Discussion

To directly separate long-lived MA from HLLW, a single-column MAREC process was proposed and a corresponding novel microporous silica-based Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent was prepared with the content of Me2-CA-BTP as high as 32 wt%. The research found Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P exhibited good adsorption selectivity towards 241Am(III) with the uptake rate of 241Am(III) over 96% and SF Am/Eu over 75 in a wide nitric acid range of 1–3 M. In 1 M HNO3 solution, the adsorption of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P towards 241Am(III) almost reached equilibrium within an hour with the uptake rate of 96% showing rapid adsorption kinetic. With the increase of γ irradiation absorbed dose in 1 M HNO3 and 3 M HNO3 solution, the adsorption performance of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P towards 241Am(III) did not change significantly. When γ irradiation absorbed dose reached to 207 kGy, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P maintained good adsorption selectivity towards 241Am(III), indicating Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P has good resistance to γ irradiation stability. Furthermore, the continuous column separation experimental results showed that Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P can effectively and selectively separate 241Am(III) from the other fission products from simulated 3 M HNO3 HLLW with 241Am(III) recovery rate of 95.5% in 241Am(III) elution step.

In a word, Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P has great application potential in the single-column MAREC process, and is expected to establish an advanced simplified MA(III) separation process.

Methods

Reagents

FP element nitrates (FP: Sr(II), Zr(IV) and trivalent rare earths) and (NH4)6Mo7O24•4H2O were commercial reagents of analytical grade. Pd(NO3)2•2H2O was chemical pure with Pd(II) ≥ 39.5 wt% and chloridate ≤ 0.04 wt%. Ru(III) nitrosyl nitrate solution was in diluted nitric acid containing 1.5 wt% of Ru(III) with a density of 1.07 g·mL−1. 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) were from laboratory stock solution. Me2-CA-BTP was synthesized at laboratory with the purity of 97% according to the HPLC-MS test. All solutions were prepared with deionized water at 18 MΩ·cm resistance (DI water). Other agents such as nitric acid, dichloromethane, etc. were of analytical grade and used without further treatment.

Preparation of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent

The support SiO2-P with pore size of 0.6 μm, pore fraction of 0.69 and mean diameter of 50 μm was developed in the previous work39. P refers to macroreticular styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer (SDB) and is immobilized in porous silica (SiO2) particles with the content of 17–18 wt% in SiO2-P. The synthesis procedure of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent was the same as ref.40. The synthesized Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent overcame the limitation of low solubility of BTP in traditional diluents as the content of Me2-CA-BTP was as high as 32.0 wt% in the adsorbent29. The synthetic Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent was characterized by high resolution field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Sirion 200, FEI COMPANY) and the SEM image is shown in Fig. 2S.

Batch adsorption experiments

For batch adsorption experiments towards 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III), 0.1 g adsorbent was combined with 5 mL aqueous solution in a 12 mL glass vial with screw teflon cap. The mixture in the vial was shaken mechanically at 300 rpm at 25 °C for a certain time and the solid-liquid separation was realized by centrifugation. The radioactivity of 241Am(III) and 152Eu(III) in solution before and after adsorption were determined by high-purity germanium multichannel gamma spectrometer (CANBERRA) at 59.5 and 121.78 keV respectively, while the concentrations of non-radioactive FP were determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES: Shimadzu ICPS-7510).

The distribution coefficient K d (mL·g−1), separation factor SF A/B and uptake rate E (%) which are key factors in solid-liquid adsorption are calculated by Equation (3), (4) and (5), respectively.

where A o, A e denote the radioactivity of metal ions in the aqueous phase before and after adsorption, respectively, Bq·mL−1. V (mL) indicates the volume of aqueous phase and W (g) is the mass of dry Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P.

Column separation experiments

Column separation experiments for simulated HLLW solution were carried out using a glass column with 5 mm in diameter and 500 mm in length. 5 g Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent was transferred to the column in the slurry state under atmosphere. The column volume (CV) of the adsorbent bed was 9.8 cm3. The column was kept at a constant temperature (35 °C) with water jacket. Prior to the separation experiment, the adsorbent in column was pre-equilibrium by passing 50 mL of 3 M HNO3. The simulated HLLW contained 5 m mol/L for each FP (Sr, Y, Zr, Mo, Ru, Pd, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd, Dy) and 500 Bq/mL 241Am(III) in 3 M HNO3 solution. All the mobile phase was pumped at 0.1 mL/min and the effluents were collected by a fractional collector. The metal concentrations in the effluents without radioactivity were determined by ICP-AES while 241Am(III) was determined by high-purity germanium multichannel gamma spectrometer.

Statistical analysis

Each batch adsorption experiment was conducted in double parallel, and batch adsorption values used are means ± SD.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Madic, C. et al. Futuristic back-end of the nuclear fuel cycle with the partitioning of minor actinides. J. Alloy Compd. 444-445, 23–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.05.051 (2007).

HILL, D. J. Nuclear energy for the future. Nat. Mater. 7, 680–682 (2008).

Angino, E. E. High-level and long-lived radioactive waste disposal. American. Association for the Advancement of Science 198, 885–890, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4320.885 (1977).

Dares, C. J., Lapides, A. M., Mincher, B. J. & Meyer, T. J. Electrochemical oxidation of 243Am(III) in nitric acid by a terpyridyl-derivatized electrode. Science 350, 652–655, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac9217 (2015).

Hill, C. Overview of recent advances in An(III)/Ln(III) separation by solvent extraction. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc.: A Series of Advances, 119-193 (2009).

Runde, W. H. & Mincher, B. J. Higher oxidation states of americium: preparation, characterization and use for separations. Chemical reviews 111, 5723–5741, https://doi.org/10.1021/cr100181f (2011).

Choppin, G. R. Comparison of the solution chemistry of the actinides and lanthanides. J. Less-common Metals 93(2), 323–330, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(83)90177-7 (1983).

Wang, X. et al. Different Interaction Mechanisms of Eu(III) and 243Am(III) with Carbon Nanotubes Studied by Batch, Spectroscopy Technique and Theoretical Calculation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11721–11728, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b02679 (2015).

Yin, L. et al. Synthesis of layered titanate nanowires at low temperature and their application in efficient removal of U(VI). Environ. Pollut. 226, 125–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.03.078 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Macroscopic and Microscopic Investigation of U(VI) and Eu(III) Adsorption on Carbonaceous Nanofibers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 4459–4467, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b00058 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Application of graphene oxides and graphene oxide-based nanomaterials in radionuclide removal from aqueous solutions. Sci. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-016-1168-x (2016).

Ansari, S. A., Pathak, P., Mohapatra, P. K. & Manchanda, V. K. Aqueous partitioning of minor actinides by different processes. Sep. Purif. Rev. 40, 43–76, https://doi.org/10.1080/15422119.2010.545466 (2011).

Modolo, G., Wilden, A., Geist, A., Magnusson, D. & Malmbeck, R. A review of the demonstration of innovative solvent extraction processes for the recovery of trivalent minor actinides from PUREX raffinate. Radiochim. Acta. 100, 715–725, https://doi.org/10.1524/ract.2012.1962 (2012).

Jianchen, W. & Chongli, S. Hot test of trialkyl phosphine oxide (TRPO) for removing actinides from highly saline high-level liquid waste (HLLW). Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 19, 231–242, https://doi.org/10.1081/sei-100102693 (2001).

Arai, K. & Yamashita, M. M. H., Hiroshi Tomiyasu & Ikeda, Y. Modified truex process for the treatment of high-level liquid waste. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 34, 521–526, https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.1997.9733700 (1997).

Tachimori, S. & A, H. N. Extraction of some elements by mixture of DIDPA-TBP and its application to actinoid partitioning process. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 19, 326–333, https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.1982.9734149 (1982).

Musikas, C.; Vitorge, P. & Pattee, D. Progress in trivalent actinide lanthanide group separation. Proc. Internat. Solvent Extr. Conf. (ISEC’83). 6-8 (1983)

Magnusson, D. et al. Demonstration of a sanex process in centrifugal contactors using the CyMe4‐BTBP molecule on a genuine fuel solution. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 27, 97–106, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366290802672204 (2009).

Zhu, Y., Chen, J. & Jiao, R. Extraction of Am(III) and Eu(III) from nitrate solution with purified cyanex 301. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 14, 61–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366299608918326 (2007).

Kolarik, Z., Mullich, U. & Gassner, F. Extraction of Am(III) and Eu(III) nitrates by 2-6-di-(5,6-dipropyl-1,2,4-triazin-3-yl)pyridines 1. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 17, 1155–1170, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366299908934641 (1999).

Kolarik, Z., Müllich, U. & Gassner, F. Selective extraction of Am(III) over Eu(III) by 2,6-ditriazolyl-and2,6-ditriazinylpyridines. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 17, 23–32, https://doi.org/10.1080/07360299908934598 (1999).

Magnusson, D., Christiansen, B., Malmbeck, R. & Glatz, J.-P. Investigation of the radiolytic stability of a CyMe4-BTBP based SANEX solvent. Radiochim Acta 97, 497–502, https://doi.org/10.1524/ract.2009.1647 (2009).

Beele, B. B., Müllich, U., Schwörer, F., Geist, A. & Panak, P. J. Systematic modifications of BTP-type ligands and effects on the separation of trivalent lanthanides and actinides. Procedia Chemistry 7, 146–151, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proche.2012.10.025 (2012).

Weigl, M., Geist, A., Müllich, U. & Gompper, K. Kinetics of Americium(III) extraction and back extraction with BTP. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 24, 845–860, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366290600948582 (2006).

Bhattacharyya, A. et al. Ethyl-bis-triazinylpyridine (Et-BTP) for the separation of americium(III) from trivalent lanthanides using solvent extraction and supported liquid membrane methods. Hydrometallurgy 99, 18–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2009.05.020 (2009).

Bhattacharyya, A. et al. Liquid-liquid extraction and flat sheet supported liquid membrane studies on Am(III) and Eu(III) separation using 2,6-bis(5,6-dipropyl-1,2,4-triazin-3-yl)pyridine as the extractant. J. Hazard Mater. 195, 238–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.08.033 (2011).

Geist, A. et al. 6,6′‐Bis(5,5,8,8‐tetramethyl‐5,6,7,8‐tetrahydro‐benzo[1,2,4]triazin‐3‐yl)[2,2′]bipyridine, an effective extracting agent for the separation of americium(III) and curium(III) from the lanthanides. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 24, 463–483, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366290600761936 (2006).

Trumm, S., Geist, A., Panak, P. J. & Fanghänel, T. An improved hydrolytically-stable bis-triazinyl-pyridine (btp) for selective actinide extraction. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 29, 213–229, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366299.2011.539129 (2011).

Ning, S. et al. Evaluation of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent for the separation of minor actinides from simulated HLLW. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 303, 2011–2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-014-3651-7 (2015).

Ning, S., Zou, Q., Wang, X., Liu, R. & Wei, Y. Adsorption behavior of Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent toward MA(III) and Ln(III) in nitrate solution. Sci. China Chem. 59, 862–868, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11426-015-0390-2 (2016).

Christoph Wagner, U. M., Geist, A. & Petra J. Panak. Selective extraction of Am(III) from PUREX raffinate the amsel system. Solvent Extr. Ion. Exc. 34, 103–113, https://doi.org/10.1080/07366299.2015.1129192 (2016).

E., K. et al. Development of a simplified MA separation process. CYRIC Annual Report (2009).

Usuda, S. et al. Development of a simplified separation process of trivalent minor actinides from fission products using novel R-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbents. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 49, 334–342, https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2012.660018 (2012).

Ning, S., Zou, Q., Wang, X., Liu, R. & Wei, Y. Adsorption mechanism of silica/polymer-based 2,6-bis(5,6-diisohexyl-1,2,4-triazin-3-yl)pyridine adsorbent towards Ln(III) from nitric acid solution. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 53, 1417–1425, https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2015.1123122 (2016).

XinPeng, W., ShunYan, N., RuiQin, L. & YueZhou, W. Stability of isoHex-BTP SiO2-P adsorbent against acidic hydrolysis and γ-irradiation. Sci. China Chem. 57(11), 1464–1469, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11426-014-5200-1 (2014).

Zou, Q., Liu, R., Ning, S., Wang, X. & Wei, Y. Recovery of palladium by silica/polymer-based 2,6-bis(5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-5,8,9,9-tetramethyl-5,8-methano-1,2,4-benzotriazin-3-yl)pyridine adsorbents from high level liquid waste. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 54, 569–577, https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2017.1298481 (2017).

Ning, S. et al. Evaluation study on silica/polymer-based CA-BTP adsorbent for the separation of minor actinides from simulated high-level liquid wastes. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 307, 993–999, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-015-4248-5 (2016).

Liu, R. et al. Adsorption behavior of actinides and some typical fission products by silica/polymer-based isoHex-BTP adsorbent from nitric acid solution. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 303, 681–691, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-014-3472-8 (2015).

WEI, Y., KUMAGAI, M. & TAKASHIMA, Y. Studies on the separation of minor actinides from high-level wastes by extraction chromatography using novel silica-based extraction resins. Nucl. Technol. 132, 413–423, https://doi.org/10.13182/NT00-A3154 (2000).

Wei, Y. Z., Hoshi, H., Kumagai, M., Asakura, T. & Morita, Y. Separation of Am(III) and Cm(III) from trivalent lanthanides by 2,6-bistriazinylpyridine extraction chromatography for radioactive waste management. J Alloy. Compd. 374, 447–450, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2003.11.059 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This whole study was carried out under the support of the National Natural Science Foundation with the Project No. 91126006, No. 11305102, No. 11705032.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. Wei and S.Y. Ning conceived the project. X.P. Wang and W.Q. Shi carried out the synthesis and characterization analysis. S.Y. Ning and Q. Zou Aided in separation work and the radiation stability evaluation. F.D. Tang and L.F. He aided in the radioactivity test. All authors discussed and co-wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ning, S.Y., Wang, X.P., Zou, Q. et al. Direct separation of minor actinides from high level liquid waste by Me 2 -CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent. Sci Rep 7, 14679 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14758-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14758-2

This article is cited by

-

New insight into the adsorption of ruthenium, rhodium, and palladium from nitric acid solution by a silica-polymer adsorbent

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2020)

-

Salt-free separation of 241Am(III) from lanthanides by highly stable macroporous silica-polymer based Me2-CA-BTP/SiO2-P adsorbent

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.