Abstract

Thin, binder-less zeolite NaX laminates, with thicknesses ranging between 310 to 750 μm and widths exceeding 50 mm and biaxial tensile strength in excess of 3 MPa, were produced by pulsed current processing. The NaX laminates displayed a high CO2 adsorption capacity and high binary CO2-over-N2 and CO2-over-CH4 selectivity, suitable for CO2 capture from flue gas and upgrading of raw biogas. The thin laminates displayed a rapid CO2 uptake; NaX laminates with a thickness of 310 μm were saturated to 40% of their CO2 capacity within 24 seconds. The structured laminates of 310 μm thickness and 50 mm thickness would offer low pressure drop and efficient carbon capture performance in a laminate-based swing adsorption technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zeolites, aluminophophates and carbon molecular sieves are commonly used adsorbents for gas separation, drying and gas purification1,2,3,4. Typically, the adsorbents are packed into vessels or columns and subjected to a pressure/vacuum swing adsorption process to selectively adsorb and desorb gas species5. Important requirements for adsorbents to be used in e.g. carbon capture from large power-plants, and low cost, small-scale solutions for biogas upgrading, include: low pressure drop, high uptake, high selectivity and short cycle time. Adsorbent beds consisting of packed granules or beads are simple to manufacture but suffer from large pressure drop, low volumetric efficiency and slow mass transfer coefficients. In addition, the pelletized or granulated adsorbents experience abrasion and surface wear during pressure cycling and disintegrate into fine dust particles which results in increased down times for swing adsorption equipment. Structured adsorbents in the form of monoliths, foams, honeycombs and laminates have the potential to overcome these problems4, 6. Indeed, recent work has suggested that laminated adsorbents could significantly improve the efficiency through a combination of low pressure drop, rapid mass and heat transfer, high volumetric efficiency and extended durability that is needed for volume efficient and rapid swing adsorption technologies7,8,9.

Laminated adsorbents have been produced using a non-adsorbing support e.g. metal foil, woven wire mesh, woven glass fiber mesh etc10, 11. Non-adsorbing binders, e.g. clays, are often added to improve the mechanical stability4, 12, 13. However, inert, non-adsorbing additives dilute the active components and thus result in a reduced volume efficiency. Hence, the development of new processes to produce self-standing laminated adsorbents with close dimensional tolerances and high mechanical stability without support material or addition of binders is of pivotal importance for cost- and volume-efficient gas separation processes with large flows, especially CO2 capture from power-plant flue-gas and biogas upgrading.

Binder-less processing routes of zeolites include hydrothermal transformation of inorganic binders, clay and silica, into zeolitic materials14,15,16,17 and pulsed current processing (PCP) to directly consolidate microporous powders4. We have previously shown that rapid heating of a powder body subjected to a compressive stress can generate binderless adsorbents18,19,20 with a significant mechanical strength from different types of porous powders, including zeolites and aluminophosphates.

In this study, we demonstrate that mechanically stable and thin self-standing laminates of NaX zeolite can be produced by a tailored pulsed current processing (PCP) method from NaX zeolite powder without addition of binders. We show that the laminate thickness can be easily controlled. Maximum PCP temperature and consolidation pressure were optimized to ensure a high mechanical strength and minimal loss of surface area. The PCP-produced laminates with thicknesses between 310 and 750 micrometers display hierarchical porous structure, rapid CO2 adsorption kinetics and a high mechanical stability. The thickness dependence of the CO2 adsorption kinetics of the laminates will be discussed.

Results and Discussions

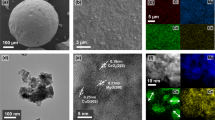

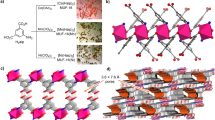

Zeolite NaX laminates of thicknesses between 310 to 750 μm were produced by pulsed current processing (PCP). Thin laminates were obtained by spreading a specific amount of NaX powder homogeneously onto a graphite paper that was placed into the PCP mold. The uniform distribution and height of the powder on the graphite paper was assured by depositing the powder while the graphite paper was rotated and the loose powder layer was consolidated by prepressing at 50 MPa. The combination of pre-deposition of a thin and homogeneous powder layer and optimization of the PCP processing conditions produced self-standing binder-free NaX laminates with a dimensional variation of 15–20 µm (Table 1). The fabrication steps of the laminates are summarized in Fig. 1 together with a conceptual illustration on how structured laminates can be used in rapid swing adsorption processes where it is essential to minimize the pressure drop and heat accumulation4, 6, 7. Laminates with diameters up to 50 mm could be fabricated by PCP of pre-deposited the homogeneous powder layers (Fig. 2). The Scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of a representative zeolite NaX laminate illustrate uniform thickness of 310 µm (Fig. 2a). The high resolution electron micrograph of NaX laminate (Fig. 2b) shows that the NaX crystals stay intact during PCP thermal treatment(see Supplementary Information, section S1). The large and thin NaX laminates are suitable for constructing adsorption based devices consisting of stacks of laminates placed with a small gap that serves as flow channels for gas transport (Fig. 1). Keefer et al. suggested that a laminate device with flow channel length of 100–200 mm and 50–75 µm channel width could operate at high cyclic frequencies21.

Schematic illustration of processing steps; powder spreading on graphite paper, pulsed current processing and the consolidated laminates. Also shown in a schematic of the concept of the cyclic application of laminates where adsorption takes place in the sorbent (laminate) top layer due to CO2 partial pressure difference between the feed gas (higher partial pressure) and the sorbent. The top layer is in direct thermal communication with the bottom layer which drives desorption in the bottom layer. Moreover, lowering of pressure or evacuation could be utilized for desorption cycle. In effect, the energy released during the exothermic adsorption process in the top layer is used by the endothermic desorption process in the bottom layer.

The biaxial tensile strength of PCP-consolidated binderless NaX laminates is over 3 MPa (Table 1). The biaxial tensile strength of the laminates is comparable to zeolite monoliths produced by PCP and by conventional processing methods incorporating significant amounts of inorganic binders9, 18, 19, 22. Biaxial strengths of 3 MPa are sufficient for low pressure swing adsorption processes where the pressure is altered between 1 bar and 6 bar23, 24. Moreover, in temperature swing based technologies, the binderless and homogeneous NaX laminates are expected to be superior to conventional laminates prepared with clay binders where the difference in thermal expansion between the clay and the zeolite could result in thermal cracking and degradation25, 26.

Mercury intrusion porosimetry data (Table 1) shows that the laminates display a hierarchical porosity with micropores defined by the structure and intrinsic porosity of the zeolite crystals, and macropores that are intraparticle voids between the NaX crystals. Previous work has shown that a hierarchical porous structure is essential for rapid gas adsorption and desorption5, 18. Optimization of the pressure and temperature during the PCP treatment retained the intraparticle voids in the PCP processed laminates due to small (local) densification at the particle contacts. The total porosity of 40% corresponds to the particle packing density of such non-spherical particles. The NaX laminates show a relatively small reduction of the BET surface area compared to the NaX powder, which suggests that the PCP-treatment only results in the formation of an amorphous phase locally at the contact points of adjacent NaX particles4, 18, 20. The NaX laminates of different thicknesses show comparable BET surface area suggesting that the pulsed current processing homogeneously consolidated the NaX powder into structured laminates of varying thicknesses.

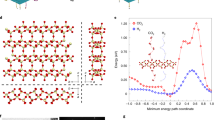

The adsorption isotherms (Fig. 3) recorded on a 310 μm thick NaX laminate show that CO2 adsorption capacity is high (5.0 mmol/g at 101 kPa at 25 °C) while the adsorption capacity of N2 and CH4 is significantly lower. We find that the PCP treatment does not influence significantly the high CO2 adsorption of zeolite NaX (see Supplementary Information, section S2), which is related to the strong interaction of the surfaces of the ionic aluminosilicate micropore cages with CO2 18, 27.

Binary CO2-over-N2 selectivity and CO2-over-CH4 selectivity are important parameters for decarbonisation of flue gas and raw biogas. We estimate CO2-over-N2 and CO2-over-CH4 thermodynamic selectivities using ideal adsorbed solution (IAS) theory28 as follows

Where \({x}_{C{O}_{2}}\), \({x}_{C{H}_{4}}\) and \({x}_{{N}_{2}}\) are mole fraction of CO2, CH4 and N2 in the adsorbed state and \({y}_{C{O}_{2}}\), \({y}_{C{H}_{4}}\) and \({y}_{{N}_{2}}\) are mole fraction of CO2, CH4 and N2 in the gas phase. Table 2 shows that the binary CO2-over-N2 selectivity is 290 and CO2-over-CH4 is 96. These high binary selectivities meet the criteria of efficient CO2 capture from power plant flue-gas and biogas upgrading27, 29.

Figure 4 shows the CO2 uptake kinetics of NaX laminates of varying thicknesses. It is important to note that CO2 adsorption kinetics on laminates are compared in the second adsorption cycle. The structured zeolite laminates to capture CO2 are potentially suitable for pressure swing adsorption (PSA) and vacuum swing adsorption (VSA) processes, where the adsorbent is regenerated either by lowering the pressure or applying vacuum5, 30. Therefore, the contributions of chemisorbed CO2 observed on zeolites in first adsorption cycle3, 31, 32 are not relevant for estimates of the adsorption kinetics of a PSA/VSA process, where physisorption of CO2 will dominate. The crystallinity, BET surface area and CO2 adsorption capacity of the structured NaX laminates is similar to the NaX powder, which suggest that the durability of the laminates should be high and could sustain PSA/VSA cycles. The CO2 adsorption kinetics on NaX laminates in Fig. 4 shows that laminates with thickness of 310 micrometers has faster CO2 adsorption compared to the thicker laminates during the first 30–60 seconds. We find that the laminate of 310 μm thickness saturates to 40% of its maximum uptake capacity (q/qmax = 0.4) in 24 seconds compared to 36 seconds for the laminate with a thickness of 600 μm and 52 seconds for the laminate with a thickness of 750 μm. The faster CO2 uptake of thinner NaX laminate suggests that the CO2 uptake of structured laminates is macroporous diffusion controlled. However, it can be seen in Fig. 4 that the CO2 adsorption kinetics at longer times does not show significant difference on the thicknesses of the laminates suggesting that the diffusion mechanism becomes complex and other factors such as heat of adsorption, thermal conductivity, heat capacity of materials and heat transfer properties play role in controlling the long-time adsorption kinetics32, 33. The kinetic data suggests that it is of importance to design the structured laminate-based devices to effectively transfer the heat of adsorption from laminates for rapid CO2 adsorption kinetics.

Conclusions

Pulsed current processing was used to produce binderless zeolite NaX laminates, 310 to 750 μm in thickness within 5% (15–20 μm) dimensional tolerances, for CO2 capture. NaX laminates demonstrated biaxial tensile strength in excess of 2 MPa. The adsorption capacity of CO2 was high 5.0 mmol/g, while the uptake of CH4 and N2 was relatively small; 0.4 mmol/g and 0.7 mmol/g, respectively. Ideal adsorption solution theory was used to estimate binary CO2-over-N2 selectivity (290 at 100 kPa at 25 °C) in 15 mol% CO2–85 mol% N2 gas mixture and CO2-over-CH4 selectivity (96 at 100 kPa at 25 °C) in 50 mol% CO2–50 mol% CH4 gas mixture. The uptake of CO2 of the NaX laminates is fast and a laminate with a thickness of 310 μm reach 40% of maximum uptake in only 24 seconds. The adsorption kinetics slows down with increasing laminate thickness but laminates with a thickness of 750 μm reach 40% of maximum uptake in less than one minute. The results suggested that NaX laminates hold great potential for selective separation of CO2 from N2 and CH4 in rapid swing adsorption processes.

Experimental

Materials

Zeolite NaX powder (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH, Germany) of 1–2 μm particle size was used as received.

Processing

Zeolite NaX laminates were produced in graphite dies of 52 mm in diameter by pulsed current processing (PCP). Spark plasma sintering (SPS) equipment (Dr. Sinter 2050, Sumitomo Coal Mining Co., Ltd., Japan) was used. The mass of NaX powder was used to optimize laminates thicknesses from 310 μm to 750 μm. The graphite dies containing NaX powder were prepressed at 50 MPa and then placed between SPS electrodes with a graphite spacer assembly. NaX powder assemblies were heated to target temperatures between 500 and 800 °C and held for 3 minutes. The heating rate adopted was 100 °C min−1. 20 MPa compressive pressure was applied throughout the heating and holding time. The laminates were ejected from graphite dies after pressureless cooling in SPS machine down to 100 °C.

Characterization

Field emission gun scanning electron microscope (FEG-SEM), JSM-7000 F (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) was used to study the microstructure of NaX lamintes. Low accelerating voltage of 5 kV was used to avoid charging up of the surfaces under observation. A PANalytical X’Pert PRO powder diffractometer (PANalytical, Almelo, Netherlands) (CuK α1 radiation λ = 1.540598 Å) was used to study the crystal structure of as-received powders and PCP processed laminates. The diffractometer was operated at at 45 kV and 40 mA and X-ray diffraction data was collected between 2θ = 5.0–60.0°. The biaxial tensile strength of the laminates was determined following ASTM F394 standard on a Zwick Z050 (Zwick GmBH Co & KG, Ulm, Germany). The biaxial tensile strength measurements were repeated for at least 5 laminates. Auto Pore III 9410 (Micromeritics, Norcross GA, USA) mercury intrusion porosimeter (MIP) was used to study the macropore volumes and pore size distributions in NaX laminates.

BET surface area, CO2 and N2 adsorption and CO2 adsorption kinetics

ASAP2020 surface area analyzer (Micromeritics, Norcross GA, USA) was used to perform nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements at −196 °C. Prior to measurements, the NaX powder and laminates were outgassed at 300 °C for 10 hours under near vacuum conditions. The nitrogen uptake at −196 °C in 0.05–0.15 p/p o relative pressure range was used to determine the Brunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) surface area of NaX powder and laminates. The same device, ASAP2020, was used for CO2, CH4 and N2 adsorption measurements at 20 and 25 °C from 0 to 101 kPa pressure. Prior to CO2, CH4 and N2 adsorption measurements, the zeolite NaX powders and laminates were outgassed at 300 °C for 10 h under near vacuum conditions. A thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) (Setaram Instruments, Caluire, France) was used to study the CO2 adsorption kinetics on zeolite NaX laminates following the experimental conditions described elsewhere18.

Adsorption models and Ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST)

Langmuir isotherm model with two parameters was used to extract the parameters from CO2, CH4 and N2 adsorption isotherms. Three adsorption isotherms were used to extract parameters. These parameters were used as input for IAS theory estimation of binary adsorption selectivity \(({\alpha }_{C{O}_{2}/{N}_{2}},{\alpha }_{C{O}_{2}/C{H}_{4}})\) following our previous work18.

References

Wang, J. et al. Recent advances in solid sorbents for CO2 capture and new development trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3478–3518 (2014).

Wang, Q., Luo, J., Zhong, Z. & Borgna, A. CO2 capture by solid adsorbents and their applications: current status and new trends. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 42–55 (2011).

Hedin, N., Andersson, L., Bergström, L. & Yan, J. Adsorbents for the post-combustion capture of CO2 using rapid temperature swing or vacuum swing adsorption. Appl. Energy 104, 418–433 (2013).

Akhtar, F., Andersson, L., Ogunwumi, S., Hedin, N. & Bergström, L. Structuring adsorbents and catalysts by processing of porous powders. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 4, 1643–1666 (2014).

Ruthven, D. M., Farooq, S. and Knaebel, K. S. Pressure swing adsorption (VCG Publishers, 1994).

Rezaei, F. & Webley, P. A. Structured adsorbents in gas separation processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 70, 243–256 (2010).

Rezaei, F. & Webley, P. A. Optimal design of engineered gas adsorbents: Pore-scale level. Chem. Eng. Sci. 69, 270–278 (2012).

Rezaei, F. Optimization of Structured Adsorbents for Gas Separation Processes. PhD Thesis at Luleå University of Technology, ISBN 978-91-7439-233-3 (2011).

Ojuva, A., Akhtar, F., Tomsia, A. P. & Bergström, L. Laminated adsorbents with very rapid CO2 uptake by freeze-casting of zeolites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 2669–2676 (2013).

Keefer, B. G. Extraction and concentration of a gas component. US Patent US5 082, 473 (1992).

Keefer, B. et al. Adsorbent coating compositions, laminates and adsorber elements comprising such compositions and methods for their manufacture and use. US Patent Application, US20020170436 (2002).

Satterfield, C. N. Heterogeneous catalysts in industrial practice (1996).

Li, Y. Y., Perera, S. P., Crittenden, B. D. & Bridgwater, J. The effect of the binder on the manufacture of a 5A zeolite monolith. Powder Technol. 116, 85–96 (2001).

Pavlov, M. L., Travkina, O. S., Basimova, R. A., Pavlova, I. N. & Kutepov, B. I. Binder-free syntheses of high-performance zeolites A and X from kaolin. Pet. Chem. 49, 36–41 (2009).

Pavlov, M., Basimova, R. & Travkina, O. Improvement of synthesis methods of powdery mordenite type zeolite. Oil gas Bus. 459–469 (2012).

Rauscher, M., Selvam, T., Schwieger, W. & Freude, D. Hydrothermal transformation of porous glass granules into ZSM-5 granules. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 75, 195–202 (2004).

Scheffler, F. et al. Transformation of porous glass beads into MFI-type containing beads. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 55, 181–191 (2002).

Akhtar, F., Liu, Q., Hedin, N. & Bergström, L. Strong and binder free structured zeolite sorbents with very high CO2-over-N2 selectivities and high capacities to adsorb CO2 rapidly. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7664–7673 (2012).

Akhtar, F., Ojuva, A., Wirawan, S. K., Hedlund, J. & Bergström, L. Hierarchically porous binder-free silicalite-1 discs: a novel support for all-zeolite membranes. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 8822–8828 (2011).

Vasiliev, P. et al. Strong hierarchically porous monoliths by pulsed current processing of zeolite powder assemblies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 732–737 (2010).

Keefer, B., Carel, A., Sellars, B., Shaw, I., & Larisch, B. Adsorbent laminate structures. US Patent No. US 6692626B2 (2004).

Ojuva, A. et al. Mechanical performance and CO2 uptake of ion-exchanged zeolite A structured by freeze-casting. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25, 2607–2618 (2015).

Akhtar, F. et al. Aluminophosphate monoliths with high CO2-over-N2 selectivity and CO2 capture capacity. RSC Adv. 4, 55877–55883 (2014).

Simmons, J. M., Wu, H., Zhou, W. & Yildirim, T. Carbon capture in metal–organic frameworks—a comparative study. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2177–2185 (2011).

David, E. Mechanical strength and reliability of the porous materials used as adsorbents/catalysts and the new development trends. Arch. Mater. Sci. Eng. 73, 5–17 (2015).

Argyle, M. & Bartholomew, C. Heterogeneous Catalyst Deactivation and Regeneration: A Review. Catalysts 5, 145–269 (2015).

Harlick, P. J. E. & Tezel, F. H. A Novel Solution Method for Interpreting Binary Adsorption Isotherms from Concentration Pulse Chromatography Data. Adsorption 6, 293–309 (2000).

Myers, A. L. & Prausnitz, J. M. Thermodynamics of mixed-gas adsorption. AIChE J. 11, 121–127 (1965).

Bacsik, Z., Cheung, O., Vasiliev, P. & Hedin, N. Selective separation of CO2 and CH4 for biogas upgrading on zeolite NaKA and SAPO-56. Appl. Energy 162, 613–621 (2016).

Kumar, R. Vacuum Swing Adsorption Process for Oxygen Production–-A Historical Perspective. Sep. Sci. Technol. 31, 877–893 (1996).

Liu, Q. et al. NaKA sorbents with high CO2-over-N2 selectivity and high capacity to adsorb CO2. Chem. Commun. 46, 4502–4504 (2010).

Cheung, O., Bacsik, Z., Liu, Q., Mace, A. & Hedin, N. Adsorption kinetics for CO2 on highly selective zeolites NaKA and nano-NaKA. Appl. Energy 112, 1326–1336 (2013).

Do Duong, D. Adsorption Analysis: Equilibria and Kinetics (Imperial College Press, 1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Swedish Research Council (VR) and the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (VINNOVA) through the Berzelii Center EXSELENT on Porous Materials and Corning Incorporated; USA. Farid Akhtar acknowledges Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF) for Infrastructure Fellowship Grant No. RIF14–0083 and Danish Innovation Fund for Grant. No. 5157–00008 A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the work. S.O. defined the structure and property parameters. F.A. performed experiments and analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. S.O. and L.B. provided helpful suggestions for analysis, manuscript writing and revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akhtar, F., Ogunwumi, S. & Bergström, L. Thin zeolite laminates for rapid and energy-efficient carbon capture. Sci Rep 7, 10988 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10518-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10518-4

This article is cited by

-

Adsorption of carbon dioxide and water vapor on fly-ash based ETS-10

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.