Abstract

As diversity among patient populations continues to grow, racial and ethnic diversity in the neurology workforce is increasingly essential to the delivery of culturally competent care and for enabling inclusive, generalizable clinical research. Unfortunately, diversity in the workforce is an area in which the field of neurology has historically lagged and faces formidable challenges, including an inadequate number of trainees entering the field, bias experienced by trainees and faculty from minoritized racial and ethnic backgrounds, and ‘diversity tax’, the disproportionate burden of service work placed on minoritized people in many professions. Although neurology departments, professional organizations and relevant industry partners have come to realize the importance of diversity to the field and have taken steps to promote careers in neurology for people from minoritized backgrounds, additional steps are needed. Such steps include the continued creation of diversity leadership roles in neurology departments and organizations, the creation of robust pipeline programmes, aggressive recruitment and retention efforts, the elevation of health equity research and engagement with minoritized communities. Overall, what is needed is a shift in culture in which diversity is adopted as a core value in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

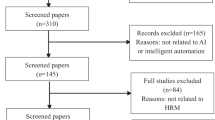

Many of the most common and debilitating disorders in neurology disproportionately affect people who belong to racial and ethnic groups that are minoritized, that is, systemically marginalized and disadvantaged relative to the dominant population. Despite this fact, the neurology workforce has historically lacked racial and ethnic diversity (Fig. 1). Individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic or Native American, or members of other minoritized racial and ethnic groups (hereafter referred to as minoritized) are underrepresented throughout the field of medicine, and like other fields, neurology suffers from a poor track record in this regard. For example, although Black individuals represent approximately 3.8% of all medical school faculty, their representation among neurology faculty is 2.5%1,2. This level of racial and ethnic diversity is mid-range among all medical subspecialties but is lower than that of related medical fields such as internal medicine (3.8%) and psychiatry (3.9%)3. Moreover, as is the case in many medical subspecialties, incremental increases in racial and ethnic diversity seen among US neurologists over time have not kept pace with rapid demographic shifts in the populace4,5. In other words, although the neurology workforce is slowly becoming more diverse, it is losing ground compared with the growing diversity of the patients served by the field.

A number of formidable challenges hinder the achievement of greater racial and ethnic diversity in neurology. These challenges include inadequate numbers of trainees from minoritized backgrounds entering the field, as well as the various challenges to career development faced by minoritized neurologists. This Review addresses the important benefits of advancing racial and ethnic diversity in the neurology workforce, the challenges faced by the field with respect to advancing diversity and several potential steps that can be taken to achieve greater success. Importantly, although this Review focuses on people who are minoritized by virtue of their racial or ethnic identities, the article is in no way intended to diminish the importance of empowering individuals of all genders, sexual orientations, abilities and socioeconomic backgrounds in neurology. In addition, because race is a social construct, the specific populations that are considered to be minoritized vary widely with differences in geography, history and culture. This Review largely limits its scope to racial and ethnic diversity in the US context, although direct or indirect parallels might be drawn to workforce diversity in neurology elsewhere.

Diversity is critical to neurology

To understand why increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the workforce is a compelling interest in neurology, we must first examine the benefits that this brings to the field and the threat posed by its absence. Certainly, increasing diversity in neurology is important to promote greater equity of opportunity for historically disadvantaged individuals who become neurologists. However, diversity in the neurology workforce is also essential for advancing the needs of the field itself (Box 1). In this section, we address how racial and ethnic diversity in neurology can improve care for patients disproportionately impacted by neurological disease, increase cultural competency, mitigate racism in the practice of neurology and enhance the external validity and impact of neurology research.

Diversity promotes health equity

Mounting evidence demonstrates that neurological disorders are often more prevalent and burdensome among minoritized racial and ethnic groups than among people who are white. For example, both stroke and Alzheimer disease — the leading neurological causes of mortality and morbidity both in the USA and globally — are heavily overrepresented among people who identify as Black or Hispanic6. Black individuals have greater incidence of other common, serious conditions, such as epilepsy and traumatic brain injury, than white people7,8,9. Furthermore, even disorders such as multiple sclerosis that have historically been conceptualized as being rare in communities of colour are increasingly recognized as being both common and burdensome among Black people10,11. In addition to having a higher risk of developing many neurological disorders, people from minoritized racial and ethnic groups face greater barriers to receiving neurological care, often receive lower quality care when they are seen by neurologists and experience worse health outcomes related to neurological disorders than people who are white9,12. These disparities in disease prevalence, severity, health-care access and treatment outcomes are the consequence of pervasive systemic and structural racism, including racism in the practice of medicine12,13.

Populations of minoritized racial and ethnic groups are also typically severely underrepresented in clinical trials aimed at developing treatments for the very neurological disorders that disproportionately impact them. For instance, despite their significantly increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease relative to white people, Black individuals were conspicuously underrepresented in trials that were instrumental in the approval of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody medications by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)14,15. Including populations from diverse backgrounds in clinical trials is critical to the external validity of study results in at least two ways. First, studies that include participants from minoritized populations are likely to include people who have experienced a wider range of structural and social determinants of health, which have a profound influence on health outcomes16,17. Second, although race is a social construct and is not determined by genetics, trials with more diverse populations are more likely to capture relevant genetic features that are differentially represented across groups with different ancestries18.

The absence of diversity in clinical trials threatens the external validity of therapeutic advances in neurology by undermining its applicability to broader populations19. Indeed, evidence suggests that a number of commonly used medications are either less effective or more dangerous in certain populations in which they had not been tested before their approval and widespread use20,21. As the demographic distribution of the USA, Canada, Australia and many countries in western Europe continue to shift towards becoming ‘majority minority’22, neurology must adapt to better serve a growing number of patients who are disproportionately affected by racial and ethnic disparities in neurological disorders, and to mitigate the broader impacts of racism on neurological health and the practice of neurology.

A crucial step that the field of neurology can take to advance the care of people from minoritized racial and ethnic groups is to ensure that individuals from these groups are well represented in its workforce. Although clinicians and researchers who do not belong to minoritized groups can and in many cases do commit themselves to serving the needs of communities of colour, people who are from minoritized backgrounds are especially likely to do so23,24. Patients who identify as Black, Hispanic or from another minoritized group face disproportionate barriers to accessing neurological care. Evidence indicates that non-Hispanic Black people with neurological symptoms are 30% less likely to be seen by a neurologist, and Hispanic people with neurological symptoms are 40% less likely to see a neurologist, than non-Hispanic white people25. One important barrier to access to neurologists for minoritized people in the USA is the geographical disparity between where neurologists practice — mostly in or near major metropolitan centres — and where minoritized people reside, which is mostly in rural regions26,27. Evidence suggests that physician trainees from minoritized backgrounds are more willing to serve in medically underserved regions of the country than their peers28. Increasing the proportion of neurologists who are committed to serving minoritized populations might help to increase access for individuals from these groups.

In addition to enhancing the clinical focus of the field on people from minoritized racial and ethnic backgrounds, increasing diversity in the neurology workforce is also likely to strengthen the commitment of the field to research that promotes health equity. A 2019 study by Hoppe and colleagues that examined the gap in the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding between Black and white researchers found that research by investigators who are Black was disproportionately focused on work at the community and population level and on topics such as health disparities compared with their white colleagues29. Thus, in both clinical care and research, greater involvement of neurologists from minoritized racial and ethnic groups is likely to strengthen the focus on these populations in neurology.

Diversity mitigates discrimination

Racial and ethnic diversity in the clinician workforce positively impacts the experience of care for people from minoritized populations. Converging evidence across the spectrum of medical specialties has shown that racism directly impacts the practice of medicine, such that patients from minoritized groups often receive inferior, discriminatory care13. This observation is certainly true in the field of neurology. For instance, Black people have been shown to be less likely than white people to receive tissue plasminogen activator or endovascular procedures — treatments used to restore blood flow to the brain in the setting of acute stroke30. In addition, Black individuals are less likely than white individuals to be administered appropriate medications for dementia, seizures and movement disorders31,32,33, and are less likely to receive appropriate surgical intervention for conditions such as epilepsy and Parkinson disease34,35. Evidence suggests that greater diversity in clinical settings is associated with greater cultural competence and cultural sensitivity in decision-making. These traits allow clearer insight into the social, psychological and cultural needs of individuals of all backgrounds, enable more effective communication with health-care providers across cultures and facilitate more optimal care of patients regardless of their backgrounds. In diverse clinical teams, this enhanced cultural competence and sensitivity are experienced not only by people who are from minoritized groups themselves but also by team members who do not belong to minoritized groups36,37.

Although a detailed evaluation of the reasons for unequal health-care delivery is beyond the scope of this Review, implicit bias — the inadvertent tendency to act in accord with unconscious learned associations involving groups of people38 — probably has a substantive role39,40. Here diversity in the neurology workforce can be of great benefit, as greater racial and ethnic diversity in the workforce has been shown to be associated with reduction in racial bias among people within the workforce who are not from minoritized groups41,42,43. In addition, several studies have demonstrated that patients from minoritized populations can experience greater ease, trust and satisfaction when interacting with clinicians of similar racial, ethnic, linguistic or cultural backgrounds44,45,46. Studies suggest that, among some Black patients, racial concordance with clinicians increases the engagement of patients with aspects of their care and improves survival-related outcomes47,48. Thus, increasing workforce diversity in neurology might improve the quality of care that minoritized patients receive, as well as enhancing patient satisfaction in the way that the care is delivered to them. Improving the diversity of the neurology workforce alone will not bring about the systemic changes in health insurance policy, barriers to access and systemic racism required to fully address health disparities in neurology. However, increasing the proportion of neurologists who are committed to serving minoritized populations is an important component of a necessarily multifaceted strategy to improve neurological care for patients from these groups.

Diversity enhances performance

In addition to specific benefits related to clinical care and research involving minoritized populations, increased diversity in neurology is also likely to have broad, positive effects on organizational and team performance. The impact of workforce diversity has been studied in various fields including business, law, science and medicine, and converging evidence indicates that more diverse groups are more creative and generally higher-performing than those that are homogenous49. For instance, scientific papers written by teams of authors with more ethnic diversity have been shown to receive more citations and are published in higher impact journals than papers written by ethnically homogenous teams50. Similar effects have been demonstrated with respect to the gender diversity of research teams51.

Evidence suggests that groups that include individuals who come from a wide range of backgrounds, for example, different racial and ethnic backgrounds, geographical origins, genders and ages, tend to have more cognitive diversity, meaning they bring a wider range of perspectives, which in turn leads to greater creativity and increased capacity to search for new information49,52. Thus, in addition to any benefits that workforce diversity brings to minoritized individuals themselves, increasing diversity in neurology teams, departments and organizations is a useful strategy for enhancing organizational excellence. Importantly, the benefits of diversity on team performance are not automatic. Homogenous teams have been shown to outperform diverse teams when the diverse teams have poor work dynamics and marginalize their members53. Diverse teams outperform homogenous teams only when they are situated in inclusive workplace cultures.

In summary, diversity in the neurology workforce offers many important benefits, including but not limited to an increased focus on the needs of medically underserved populations, more valid clinical research studies, reduced disparities in care delivery, improved experiences for patients from minoritized populations and broadly enhanced team performance. In the next section of this Review, we address reasons why achieving greater diversity in the neurology workforce has proven to be so elusive.

Barriers to achieving diversity

The challenge of achieving diversity in the workforce in medicine and academia is often compared with a ‘leaky pipeline’. By this account, the problem is that at every step along the career development pathway attrition occurs among people who belong to minoritized racial and ethnic groups, such that very few individuals successfully complete training to enter their profession. However, this metaphor does not provide an adequate explanation for the lack of diversity in medicine and academia, insofar as the leaky pipeline is a symptom rather than the cause of the problem. To address the problem of attrition among individuals pursuing careers in neurology, the various factors that make pursuing a career in neurology either infeasible or unappealing for many minoritized people must be recognized (Box 2). This section briefly addresses the obstacles that severely limit the number of people from minoritized backgrounds who complete medical school and choose to train in neurology. The section then focuses on challenges that neurologists from minoritized groups often face throughout their career development.

Limited candidates

Perhaps the most formidable obstacle facing efforts to enhance racial and ethnic diversity in neurology is the persistently low numbers of people from minoritized groups attending medical schools. A comprehensive discussion of the many factors that contribute to this challenge is beyond the scope of this Review. However, important considerations include the underrepresentation of minoritized students at the competitive colleges and universities from which medical school applicants are disproportionately admitted, and high attrition rates among minoritized students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields during their undergraduate years54,55. The root causes of these problems are complex and relate to disparities in educational opportunities and support throughout primary and secondary education, as well as a wide range of other structural and social disadvantages that make academic success and preparedness for college and medical school more challenging for minoritized students56. Unfortunately, a ruling of the Supreme Court of the USA in 2023 against the consideration of race as a limited criterion for admission in higher education threatens to further widen disparities in undergraduate and medical school diversity57.

In addition to the overall underrepresentation of people from minoritized racial and ethnic backgrounds in medical school, neurology also remains a relatively unpopular career choice for these individuals. The reasons for this are not fully understood. However, a 2022 survey of Black, white and Asian medical students by Railey and Spector suggests that many Black medical students are motivated to choose specialties other than neurology because they have strong pre-existing interests in other fields and because they feel that they have had inadequate exposure to neurology58. Both of these factors suggest that earlier, greater exposure to neurology might be helpful for increasing the number of Black students who consider careers in neurology. In the same survey, a greater proportion of Black students than of Asian and white students indicated that the lack of racial diversity in neurology had a negative influence on their view of neurology as a career. Minoritized students might have difficulty envisioning themselves as future neurologists owing to the lack of neurologists of colour to look to as role models. In the words of the civil rights activist, Marian Wright Edelman, “If you can’t see it, you can’t be it.”

Bias and discrimination

A common obstacle facing minoritized people in professional environments of all types is the conscious or unconscious racial bias of colleagues, supervisors and trainers, as well as the biased structures and systems within which these individuals work. Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that racial bias can negatively impact professional success. For instance, possessing a name that does not align with a white European background can negatively affect decisions about whether to interview and hire job applicants59. Similarly, the perceived race of an individual can impact the responsiveness of their teachers and mentors to requests for guidance60, which in turn can make it difficult for minoritized people to build their professional networks and fill career knowledge gaps. In addition, evidence suggests that women and racially minoritized individuals are given worse performance evaluations in the workplace, including in medical settings, when their performance is comparable with that of their peers who are men and white, respectively59,61,62,63. These forms of unequal treatment of minoritized people in the workplace are further compounded by the frequent expression of microaggressions — largely unintended slights that reflect unconscious biases or beliefs about a group of individuals64.

Collectively, these expressions of bias communicate the message that people from minoritized groups do not belong in medical and academic settings, contributing to the self-perception among these individuals of not belonging or of being ‘imposters’ in these environments despite their qualifications65. Relatedly, acute awareness of the existence of negative stereotypes regarding the intelligence, competence and work ethic of minoritized people imposes psychological burdens that can negatively impact performance, a phenomenon known as ‘stereotype threat’66,67,68. Finally, physicians from minoritized racial and ethnic groups often experience mistreatment and discrimination by patients and their loved ones, which can contribute to professional dissatisfaction and burnout69.

Preparation gaps

A major problem facing many people from minoritized racial and ethnic backgrounds who are attempting to pursue careers in medicine and academia are potential gaps in process knowledge and experience that are associated with disadvantaged backgrounds. For instance, evidence published in 2023 indicates that, on average, American Indian or Alaska Native, Black and Hispanic students suffer from lower parental education, attend colleges with fewer resources and receive poorer pre-health academic advising, all of which are associated with lower medical college admissions test (MCAT) performances70.

Trainees from disadvantaged backgrounds often encounter challenges in perceiving and acclimating to the culture of medicine, including its ‘hidden curriculum’ of behavioural norms and unspoken strategies for success. These include but are not limited to fitting in with one’s clinical teams, navigating the hierarchical relationships found in medicine, and pursuing various professional accolades and leadership positions.71 People from minoritized groups also suffer from greater workplace social isolation and have smaller professional networks, which negatively affects their career development72,73. One especially important category of professional connection that individuals from minoritized groups might fail to develop is close relationships with career mentors who would otherwise be well positioned to help fill in process knowledge gaps and advance their professional goals74.

Financial pressures

Financial obstacles to achieving diversity in neurology and medicine are also present. The USA has a wide and persistent racial and ethnic disparity in wealth, with Black households holding only 2.9% of US wealth while accounting for 15.6% of the population75. Similarly, Hispanic households account for 2.8% of US wealth and 10.9% of the population75. Massive disparities in wealth influence the burden of educational debt experienced by minoritized people. In the USA, Black students often face profound disparities in educational debt compared with other students76. These additional financial constraints negatively impact medical and academic career development in various ways. Many disadvantaged students must take on more employment hours concurrent to their education, which challenges their ability to achieve high levels of academic success and can jeopardize their competitiveness for medical schools or residency programmes70,77.

Whether financial demands negatively affect the retention of minoritized people who have successfully become neurologists is unclear; however, financial status might influence decisions about important career factors such as practice type and location. For instance, evidence suggests that minoritized medical students who anticipate higher levels of debt are more willing to practice their specialty in medically underserved areas as part of loan repayment programmes28.

Diversity tax

Increasing awareness of the importance of diversity in neurology, medicine and academia contributes to a complex challenge that has been termed ‘diversity tax’ (also known as ‘minority tax’). In academic environments, people from minoritized racial, ethnic and sexual and gender groups shoulder a disproportionate burden of service work to their institutions relative to their white peers and colleagues who identify as cisgender men78. Ironically, this service work often takes the form of leading the diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives of their departments, schools or organizations. Further complicating this issue is the fact that many individuals from minoritized backgrounds feel some degree of personal obligation to serve in these roles, as well as the fact that requests to pursue this work often come from well-intentioned organizations that recognize that one of the most persuasive ways to attract minoritized candidates is to showcase racial and ethnic diversity. However, for minoritized people who are primarily focused on careers in other scientific, educational or clinical areas, the nearly universal expectation that they would devote substantial time and energy to these programmes represents a potential threat to their professional development79. Even for minoritized people who do wish to focus their careers on DEI, the fact that leadership in this area is often given lesser weight in considerations for academic promotion or appointment to other related leadership roles can be problematic for their professional growth.

Overcoming barriers to diversity

Given the many formidable challenges that must be overcome to achieve greater racial and ethnic diversity in neurology, the strategies for addressing them must be multifaceted and far-reaching. In this last major section, this Review presents several strategic approaches to enhancing racial and ethnic diversity in neurology (Box 3). However, because efforts to enhance diversity must constantly adapt to address contemporary social currents, standards and laws, no list of ideas around advancing diversity can ever claim to be definitive. Rather, three broad and important strategies are outlined here: first, building effective diversity leadership in departments and organizations; second, creating robust pipelines of diverse neurology trainees at all levels; and last, elevating health equity as a focus in neurology.

Developing leaders in diversity

Addressing the many challenges to diversity in neurology requires sustained and deliberate leadership. This leadership must be expressed at many levels; however, in many neurology departments, an emerging, potentially influential leadership role with respect to diversity is that of the departmental diversity officer (or officers) and/or committees80,81,82. Neurology departments benefit greatly from appointing individuals who serve to continually reinforce DEI as core values that inform and enhance neurological clinical care, research and education. Importantly, the role of a diversity officer should be neither titular nor cosmetic. Rather, effective departmental diversity leaders must be provided with the influence, authority, support and protected time required to successfully pursue their objectives82.

Advancing diversity in neurology at the departmental level requires both commitment and action from all departmental leaders. One way to reinforce this effort is to consider one’s demonstrated dedication to advancing diversity to be one of the qualifications for consideration for all departmental leadership roles. Critically, advocacy for diversity should not be the purview of only people who are themselves members of minoritized racial and ethnic groups, as placing this diversity tax on those who are already disproportionately burdened on the basis of race is discriminatory. In addition, most neurology departments simply have too few individuals from minoritized backgrounds to achieve far-reaching diversity goals effectively on their own79.

As with neurology departments, professional societies of neurologists must similarly embrace diversity as a core organizational value. Encouragingly, the past 5 years have witnessed an intensified focus on DEI and an increase in the number and quality of diversity initiatives in major US neurological societies such as the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Neurological Association (ANA) and their associated publications83,84. In addition, societies comprising and for minoritized neurologists and neuroscientists such as the Society for Black Neurologists and Black in Neuro have emerged as communities of support for current and aspiring neurologists85.

Building diversity pipelines

In theory, one large-scale approach to increasing racial diversity in neurology training programmes would be to increase the overall representation of minoritized individuals in colleges, universities and medical schools. A rising tide lifts all boats. Unfortunately, the banning of affirmative action in higher education admissions by the US Supreme Court in 2023 is widely anticipated to, at least in the short term, result in a reduction in the number of minoritized students attending US colleges and universities57. With respect to diversity in the neurology workforce, the decision by the US Supreme Court raises at least two concerns. First, the dismantling of affirmative action at the undergraduate level might eventually diminish the pool of minoritized applicants who are competitive for admission to US medical schools. The decision on affirmative action could also be applied directly to medical school admissions processes86. These two impacts threaten to further weaken racial and ethnic diversity in medical schools, which would eventually decrease diversity in residency training programmes across medical specialties, including neurology. In addition to the decision by the US Supreme Court, increasing efforts to dismantle (DEI) programmes in education have been observed across many US states87,88, alongside mounting criticism of DEI initiatives in medical schools89,90. These programmes have historically led efforts to recruit minoritized individuals, so their dissolution also threatens to severely undermine diversity among undergraduates, medical students and eventually trainees in medical fields such as neurology.

To prevent the already leaky pipeline of trainees from minoritized groups from slowing even further, undergraduate and medical school educators will need to adopt various highly innovative, intentional measures to promote diversity86. Encouragingly, some institutions, such as the University of California Davis School of Medicine, have found innovative ways to maintain and enhance diversity in the absence of affirmative action initiatives. These include but are not limited to increasing the diversity of admissions committees and focusing on applicants who face socioeconomic disadvantages, which are concentrated in minoritized populations91. Neurology departments will probably also need to adapt to preserve and enhance diversity in postgraduate medical training. This will include a wide range of actions related to resident recruitment, including but not limited to employing diverse selection committees, pursuing more holistic, individualized evaluations of residency candidates that account for obstacles — including socioeconomic disadvantages — that applicants have overcome on their academic and professional journeys, partnering with medical schools and medical student organizations that represent minoritized groups to provide earlier and greater exposure to neurology to interested students, and creating visiting clerkships, research opportunities and mentorship programmes for minoritized students considering careers in neurology58.

Neurology programmes that are situated in areas that have large minoritized populations can also benefit from developing outreach and enrichment programmes that introduce learners at earlier stages of their education, such as undergraduates and high school students, to neurology. These programmes can help to spark interest in neurology among early learners from minoritized groups, engage neurology departments more fully with their local communities and signal to prospective trainees and students that neurology is a specialty that recognizes its relevance to underserved populations. For example, the University of Pennsylvania’s Educational Pipeline Program (formerly called the Neuroscience Pipeline Program), a highly successful 26-year-old partnership between the university and schools in its surrounding, largely Black community, combines classroom science enrichment with an afterschool programme92. This afterschool programme provides weekly case-based teaching for high school students, teaching and mentorship opportunities for undergraduate and medical student volunteers (many of whom have gone on to become neurologists), and an opportunity for community engagement for resident volunteers, and has become a draw for prospective underrepresented trainees considering the University of Pennsylvania. Professional organizations and academic societies can also be helpful in bolstering interest in neurology among minoritized medical students, undergraduates and younger trainees by sponsoring scholarships, travel awards and other early career development opportunities.

To advance diversity among neurology trainees, it is important to not only promote diversity at institutions with well-established neurology programmes but also strengthen neurology training at institutions that already have a well-established commitment to diversity. Certain institutions contribute disproportionately to the diversity of the medical workforce. For instance, despite comprising only approximately 2% of the country’s medical schools, Historically Black Medical Schools produce approximately 10% of Black physicians in the USA93,94. Unfortunately, the degree of exposure to neurology at these and other institutions where minoritized students attend in higher numbers is variable and in some cases lacking. This observation provides both a challenge and an opportunity for neurology to build new pathways for the diversification of its workforce. A recent, encouraging example of this is the Morehouse School of Medicine, which inaugurated a new residency training programme in neurology94 in 2022. Of note, this was achieved in partnership with the ANA, highlighting the role that professional organizations and societies can have in supporting the advancement of these important education and training opportunities84.

Another integral aspect of promoting racial and ethnic diversity in neurology is faculty development to ensure that people from minoritized groups who have completed the long and arduous path to becoming neurologists are able to thrive in their professional roles. Cognizant of the additional challenges that minoritized faculty members often face, neurology departments must play a part in making sure that junior faculty from minoritized racial and ethnic backgrounds are able to take full advantage of departmental and institutional career development resources and mentorship opportunities. Moreover, careful attention must be paid to the extent to which faculty from minoritized groups are being asked to shoulder the responsibility for departmental diversity efforts, whether those efforts are aligned with the personal and career goals of each faculty member, whether minoritized faculty who engage in DEI work are adequately compensated in terms of protected time, salary support and administrative assistance, and whether DEI work is given adequate weight in consideration for promotion and appointment to other leadership roles79. Professional organizations and academic societies can have an important role in career development for minoritized neurologists by developing initiatives that prepare them for leadership roles in their profession. Current examples within the field of neurology include the AAN’s Diversity Leadership Program and the Training in Research for Academic Neurologists to Sustain Careers and Enhance the Numbers of Diverse Scholars (TRANSCENDS) programme95.

Because the majority of neurologists in the USA are in private practice settings rather than neurology departments or major medical centres, considering how these providers can contribute to enhancing the diversity of the neurology workforce is important. Efforts to ensure more engagement with minoritized patients in private practice settings could facilitate greater familiarity with and interest in neurology and neurologists among minoritized communities. This goal might ultimately enhance the pipeline of minoritized people interested in neurology; many physicians were first inspired towards their careers by the clinicians who cared for them, their families or their communities. Moreover, because minoritized physicians are more likely to serve underserved communities than their peers23,24,28, increasing the diversity of the private practice workforce in neurology could help to create a virtuous cycle of greater community engagement that leads to more robust pipelines of minoritized neurologists, which in turn leads to even greater engagement.

Focusing on health equity

The ability of neurology to diversify its workforce is integrally linked to its focus on advancing health equity, and provides an opportunity for synergy between goals96. The relative absence of people from minoritized backgrounds, however, presents a classic ‘chicken-and-egg’ problem. Because minoritized individuals in medicine often gravitate towards fields in which they feel they can contribute to communities such as the ones from which they came, neurology is unlikely to attract a diverse workforce unless the field increases its emphasis on health equity and its engagement with minoritized communities. Conversely, the field of neurology will continue to struggle to successfully engage with minoritized communities if people who are themselves intimately familiar with and motivated by their lived experiences with these inequities are not well represented among its ranks. To face either challenge, both must be addressed.

An in detail discussion of the many ways the field of neurology should intensify its focus on health equity is out of the scope of this Review. However, ongoing and future efforts could include but are not limited to the following: increasing emphasis on population health and health disparities as an area of specialized research focus for neurologists; advocating for increased funding and greater visibility for leaders in these topic areas within neurology; increasing education related to neurological health disparities for medical students, residents and fellows, and instituting knowledge requirements in these areas in neurology board and subspecialty certification examinations; increasing participation of neurologists in community clinics and other efforts to diminish barriers in access for minoritized people with neurological disorders; and redoubling efforts at increasing diversity in clinical trial participation (for reviews, see Marulanda-Londoño et al.9 and Robbins et al.12). Importantly, efforts to engage with minoritized communities will be successful only if neurologists and the institutions in which they serve can create trusting, longitudinal and mutually beneficial partnerships with these populations. Although several examples exist of individual successes between neurology teams and their surrounding communities, particularly in the area of stroke care and prevention97,98,99,100, much broader engagement and investment in communities by neurologists and the institutions that they work are needed.

Conclusions

To better engage with an increasingly diverse, pluralistic populace and to better meet the needs of communities that are most severely impacted by neurological disease, the neurology workforce must more closely resemble the populations the field seeks to serve. To achieve this goal, the field must take deliberate action to enhance its racial and ethnic diversity. This effort is especially crucial now, when programmes promoting diversity are increasingly under threat. This Review has outlined a number of steps the field of neurology can take to diversify its workforce. However, meeting the challenges of neurology with respect to diversity will probably involve more than a set of specific programmes and initiatives. What might ultimately be needed is a broad shift in the culture of the field to one that enables a more diverse and inclusive vision of who goes into this specialty, why they choose to do it and how they will succeed in their profession as neurologists.

References

American Association of Medical Colleges. Faculty roster: U.S. medical school faculty. AAMC https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/report/faculty-roster-us-medical-school-faculty (2022).

Guevara, J. P., Wade, R. & Aysola, J. Racial and ethnic diversity at medical schools — why aren’t we there yet? N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1732–1734 (2021).

American Association of Medical Colleges. 2022 report on residents. AAMC https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2022/table-b5-md-residents-race-ethnicity-and-specialty (2022).

US Census Bureau. 2020 Census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. Census https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html (2021).

Lett, E., Orji, W. U. & Sebro, R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE 13, e0207274 (2018).

Xu, J., Murphy, S. L., Kochanek, K. D. & Arias, E. Mortality in the United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db456.pdf (2022).

Bautista, R. E. D. & Jain, D. Detecting health disparities among Caucasians and African-Americans with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 20, 52–56 (2011).

Brenner, E. K. et al. Race and ethnicity considerations in traumatic brain injury research: incidence, reporting, and outcome. Brain Inj. 34, 799–808 (2020).

Marulanda-Londoño, E. T. et al. Reducing neurodisparity: recommendations of the 2017 AAN Diversity Leadership Program. Neurology 92, 274–280 (2019).

Amezcua, L., Rivas, E., Joseph, S., Zhang, J. & Liu, L. Multiple sclerosis mortality by race/ethnicity, age, sex, and time period in the United States, 1999–2015. Neuroepidemiology 50, 35–40 (2018).

Langer-Gould, A., Brara, S. M., Beaber, B. E. & Zhang, J. L. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in multiple racial and ethnic groups. Neurology 80, 1734–1739 (2013).

Robbins, N. M. et al. Black patients matter in neurology: race, racism, and race-based neurodisparities. Neurology 99, 106–114 (2022).

Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (National Academies Press, 2003).

Budd Haeberlein, S. et al. Two randomized phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 9, 197–210 (2022).

van Dyck, C. H. et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 9–21 (2023).

Magnan, S. Social determinants of health 101 for health care: five plus five. NAM Perspect. https://doi.org/10.31478/201710c (2017).

Hood, C. M., Gennuso, K. P., Swain, G. R. & Catlin, B. B. County health rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 50, 129–135 (2016).

Fujimura, J. H. & Rajagopalan, R. Different differences: the use of ‘genetic ancestry’ versus race in biomedical human genetic research. Soc. Stud. Sci. 41, 5–30 (2011).

Murad, M. H., Katabi, A., Benkhadra, R. & Montori, V. M. External validity, generalisability, applicability and directness: a brief primer. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 23, 17–19 (2018).

Konkel, L. Racial and ethnic disparities in research studies: the challenge of creating more diverse cohorts. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, A297–A302 (2015).

Moyer, T. P. et al. Warfarin sensitivity genotyping: a review of the literature and summary of patient experience. Mayo Clin. Proc. 84, 1079–1094 (2009).

Vespa, J., Medina, L. & Armstrong, D. M. Demographic turning points for the United States: population projections for 2020 to 2060. Census https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf (2020).

Powe, N. R. & Cooper, L. A. Diversifying the racial and ethnic composition of the physician workforce. Ann. Intern. Med. 141, 223–224 (2004).

Kington, R., Tisnado, D. & Carlisle, D. in The Right Thing to Do, the Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions: Summary of the Symposium on Diversity in Health Professions in Honor of Herbert W. Nickens, M.D. (eds Smedley, B. D. et al.) 57–91 (National Academies Press, 2001).

Saadi, A., Himmelstein, D. U., Woolhandler, S. & Mejia, N. I. Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology 88, 2268–2275 (2017).

Occupational employment and Wages, May 2022: 29-1217 Neurologists. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291217.htm (2023).

US Census Bureau. 2020 Census demographic data map viewer. Census https://maps.geo.census.gov/ddmv/map.html (2020).

Price, M. A., Cohn, S. M., Love, J., Dent, D. L. & Esterl, R. Educational debt of physicians-in-training: determining the level of interest in a loan repayment program for service in a medically underserved area. J. Surg. Educ. 66, 8–13 (2009).

Hoppe, T. A. et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/Black scientists. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw7238 (2019).

Otite, F. O. et al. Ten-year trend in age, sex, and racial disparity in tPA (Alteplase) and thrombectomy use following stroke in the United States. Stroke 52, 2562–2570 (2021).

Begley, C. E. et al. Sociodemographic disparities in epilepsy care: results from the Houston/New York City health care use and outcomes study. Epilepsia 50, 1040–1050 (2009).

Dahodwala, N., Xie, M., Noll, E., Siderowf, A. & Mandell, D. S. Treatment disparities in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 66, 142–145 (2009).

Kalkonde, Y. V. et al. Ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia in veterans. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 28, 145–152 (2009).

Burneo, J. G. et al. Racial disparities in the use of surgical treatment for intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 64, 50–54 (2005).

Willis, A. et al. Disparities in deep brain stimulation surgery among insured elders with Parkinson disease. Neurology 82, 163–171 (2014).

Cohen, J. J., Gabriel, B. A. & Terrell, C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff. 21, 90–102 (2002).

The Rationale for Diversity in the Health Professions: A Review of the Evidence (United States Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, 2006).

American Psychological Association. Implicit bias. APA https://www.apa.org/topics/implicit-bias (2022).

Gopal, D. P., Chetty, U., O’Donnell, P., Gajria, C. & Blackadder-Weinstein, J. Implicit bias in healthcare: clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthc. J. 8, 40–48 (2021).

Schulman, K. A. et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N. Engl. J. Med. 340, 618–626 (1999).

Bai, X., Ramos, M. R. & Fiske, S. T. As diversity increases, people paradoxically perceive social groups as more similar. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 12741–12749 (2020).

Darling-Hammond, S., Lee, R. T. & Mendoza-Denton, R. Interracial contact at work: does workplace diversity reduce bias? Group Process Intergroup Relat. 24, 1114–1131 (2021).

Pauker, K., Carpinella, C., Meyers, C., Young, D. M. & Sanchez, D. T. The role of diversity exposure in whites’ reduction in race essentialism over time. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 9, 944–952 (2018).

Cooper, L. A. et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann. Intern. Med. 139, 907–915 (2003).

Moore, C. et al. It’s important to work with people that look like me’: Black patients’ preferences for patient-provider race concordance. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 10, 2552–2564 (2022).

Takeshita, J. et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2024583 (2020).

Alsan, M., Garrick, O. & Graziani, G. C. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from oakland. NBER https://doi.org/10.3386/w24787 (2018).

Snyder, J. E. et al. Black representation in the primary care physician workforce and its association with population life expectancy and mortality rates in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e236687 (2023).

Page, S. E. The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies (New Edition) (Princeton Univ. Press, 2007).

Freeman, R. B. & Huang, W. Collaboration: strength in diversity. Nature 513, 305 (2014).

Campbell, L. G., Mehtani, S., Dozier, M. E. & Rinehart, J. Gender-heterogeneous working groups produce higher quality science. PLoS ONE 8, e79147 (2013).

Hong, L. & Page, S. E. Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16385–16389 (2004).

Diversity, equity and inclusion 4.0: a toolkit for leaders to accelerate social progress in the future of work. World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/publications/diversity-equity-and-inclusion-4-0-a-toolkit-for-leaders-to-accelerate-social-progress-in-the-future-of-work/ (2020).

Chen, X. & Soldner, M. STEM Attrition: College Students’ Paths Into and Out of STEM Fields (National Center for Education Statistics, 2013).

Meyers, L. C., Brown, A. M., Moneta-Koehler, L. & Chalkley, R. Survey of checkpoints along the pathway to diverse biomedical research faculty. PLoS ONE 13, e0190606 (2018).

Darling-Hammond, L. in The Right Thing to Do, the Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions: Summary of the Symposium on Diversity in Health Professions in Honor of Herbert W. Nickens, M.D. (eds Smedley, B. D. et al.) 208–233 (National Academies Press, 2001).

Ly, D. P., Essien, U. R., Olenski, A. R. & Jena, A. B. Affirmative action bans and enrollment of students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in U.S. public medical schools. Ann. Intern. Med. 175, 873–878 (2022).

Railey, K. M. & Spector, A. R. Neurological interest and career exploration among Black medical students: perceptions and solutions for the pipeline. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 113, 654–660 (2022).

Kline, P., Rose, E. K. & Walters, C. R. Systemic discrimination among large U.S. employers. Q. J. Econ. 137, 1963–2036 (2022).

Milkman, K. L., Akinola, M. & Chugh, D. What happens before? A field experiment exploring how pay and representation differentially shape bias on the pathway into organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 1678–1712 (2015).

Anderson, J. E., Zern, N. K., Calhoun, K. E., Wood, D. E. & Smith, C. A. Assessment of potential gender bias in general surgery resident milestone evaluations. JAMA Surg. 157, 1164–1166 (2022).

Boatright, D. et al. Racial and ethnic differences in internal medicine residency assessments. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2247649 (2022).

Grimm, L. J., Redmond, R. A., Campbell, J. C. & Rosette, A. S. Gender and racial bias in radiology residency letters of recommendation. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 17, 64–71 (2020).

Weir, M. Understanding and addressing microaggressions in medicine. Dermatol. Clin. 41, 291–297 (2023).

Rice, J. et al. Impostor syndrome among minority medical students who are underrepresented in medicine. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 115, 191–198 (2023).

Ackerman-Barger, K., Valderama-Wallace, C., Latimore, D. & Drake, C. Stereotype threat susceptibility among minority health professions students. J. Best Pract. Health Prof. Diversity 9, 1232–1246 (2016).

Bullock, J. L. et al. They don’t see a lot of people my color: a mixed methods study of racial/ethnic stereotype threat among medical students on core clerkships. Acad. Med. 95, S58–S66 (2020).

Woodcock, A., Hernandez, P. R., Estrada, M. & Schultz, P. W. The consequences of chronic stereotype threat: domain disidentification and abandonment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103, 635–646 (2012).

Dyrbye, L. N. et al. Physicians’ experiences with mistreatment and discrimination by patients, families, and visitors and association with burnout. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2213080 (2022).

Faiz, J., Essien, U. R., Washington, D. L. & Ly, D. P. Racial and ethnic differences in barriers faced by medical college admission test examinees and their association with medical school application and matriculation. JAMA Health Forum 4, e230498 (2023).

Fokas, J. A. & Coukos, R. Opinion & special articles: examining the hidden curriculum of medical school from a first-generation student perspective. Neurology https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000207174 (2023).

Dyrbye, L. N. et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the united states. Arch. Intern. Med. 167, 2103–2109 (2007).

Ibarra, H. Personal networks of women and minorities in management: a conceptual framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 18, 56–87 (1993).

Beech, B. M. et al. Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical centers: a systematic review of the literature. Acad. Med. 88, 541–549 (2013).

Aladangady, A. & Forde, A. Wealth inequality and the racial wealth gap. Federal Reserve https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/wealth-inequality-and-the-racial-wealth-gap-20211022.html (2021).

Perry, A., Steinbaum, M. & Romer, C. Student loans, the racial wealth divide, and why we need full student debt cancellation. Brookings https://www.brookings.edu/articles/student-loans-the-racial-wealth-divide-and-why-we-need-full-student-debt-cancellation/ (2021).

Carnevale, A. P. Working while in college might hurt students more than it helps. CNBC https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/24/working-in-college-can-hurt-low-income-students-more-than-help.html (2019).

Gewin, V. The time tax put on scientists of colour. Nature 583, 479–481 (2020).

Williamson, T., Goodwin, C. R. & Ubel, P. A. Minority tax reform — avoiding overtaxing minorities when we need them most. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1877–1879 (2021).

Gordon Perue, G. L. et al. Development of an equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism pledge as the foundation for action in an academic department of neurology. Neurology 97, 729–736 (2021).

Harpe, J. M., Safdieh, J. E., Broner, S., Strong, G. & Robbins, M. S. The development of a diversity, equity, and inclusion committee in a neurology department and residency program. J. Neurol. Sci. 428, 117572 (2021).

Mohile, N. A. et al. Developing the neurology diversity officer: a roadmap for academic neurology departments. Neurology 96, 386–394 (2021).

Hamilton, R. H. & Hinson, H. E. Introducing the associate editors for equity, diversity, and inclusion: aligning editorial leadership with core values in neurology®. Neurology 93, 651–652 (2019).

Willis, A. et al. Strengthened through diversity: a blueprint for organizational change. Ann. Neurol. 90, 524–536 (2021).

Spector, A. R. et al. Introducing the Society of Black Neurologists. Lancet Neurol. 19, 892–893 (2020).

Hamilton, R. H., Rose, S. & DeLisser, H. M. Defending racial and ethnic diversity in undergraduate and medical school admission policies. JAMA 329, 119–120 (2023).

Wong, A. DEI came to colleges with a bang. Now, these red states are on a mission to snuff it out. USA TODAY https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2023/03/23/dei-diversity-in-colleges-targeted-by-conservative-red-states/11515522002/ (2023).

Bhaskara, V. DEI is under attack at colleges and universities. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/vinaybhaskara/2023/07/07/dei-is-under-attack-at-colleges-and-universities/ (2023).

Sailor, J. D. Don’t impose DEI at med schools. Newsweek https://www.newsweek.com/dont-impose-dei-med-schools-opinion-1727735 (2022).

Goldfarb, S. Take two aspirin and call me by my pronouns. Wall Street Journal https://www.wsj.com/articles/take-two-aspirin-and-call-me-by-my-pronouns-11568325291 (2019).

McFarling, U. L. How one medical school became remarkably diverse — without considering race in admissions. STAT https://www.statnews.com/2023/03/07/how-one-medical-school-became-remarkably-diverse-without-considering-race/ (2023).

Hamilton, R. H., Hamilton, K., Jackson, B. & Dahodwala, N. Teaching: residents in the hospital, mentors in the community: the Educational Pipeline Program at Penn. Neurology 68, E25–E28 (2007).

Table 10. U.S. medical school Black or African American graduates (alone or in combination) from Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), 1978–1979 through 2018–2019. AAMC https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-10-us-medical-school-black-or-african-american-graduates-alone-or-combination-historically (2019).

Neurology Residency Program. Morehouse School of Medicine https://www.msm.edu/Education/GME/NeurologyResidencyProgram/index.php (2024).

Tagge, R. et al. TRANSCENDS: a career development program for underrepresented in medicine scholars in academic neurology. Neurology 97, 125–133 (2021).

Ibrahim, S. A. Physician workforce diversity and health equity: it is time for synergy in missions! Health Equity 3, 601–603 (2019).

Covington, C. F. et al. Developing a community-based stroke prevention intervention course in minority communities: the DC Angels Project. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 42, 139–142 (2010).

Kleindorfer, D. et al. The challenges of community-based research: the beauty shop stroke education project. Stroke 39, 2331–2335 (2008).

Morgenstern, L. B. et al. A randomized, controlled trial to teach middle school children to recognize stroke and call 911: the kids identifying and defeating stroke project. Stroke 38, 2972–2978 (2007).

Williams, O. & Noble, J. M. ‘Hip-hop’ stroke: a stroke educational program for elementary school children living in a high-risk community. Stroke 39, 2809–2816 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Neurology thanks Temitayo Oyegbile-Chidi, Nimish Mohile, Richard Benson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

American Academy of Neurology Diversity Leadership Program: https://www.aan.com/education/diversity-leadership

American Academy of Neurology Training in Research for Academic Neurologists to Sustain Careers and Enhance the Numbers of Diverse Scholars (TRANSCENDS): https://www.aan.com/research/transcends-program

University of Pennsylvania Educational Pipeline Program: https://www.nettercenter.upenn.edu/what-we-do/university-assisted-community-schools/moelis-access-science/educational-pipeline-program

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamilton, R.H. Building an ethnically and racially diverse neurology workforce. Nat Rev Neurol 20, 222–231 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-024-00941-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-024-00941-3