Abstract

There is a scarcity of evidence on subjectively reported cognitive difficulties in individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis and whether these self-perceived cognitive difficulties may relate to objective cognitive deficits, psychopathology, functioning, and adherence to cognitive remediation (CR). Secondary, exploratory analyses to a randomized, clinical trial were conducted with 52 UHR individuals receiving a CR intervention. Participants completed the Measure of Insight into Cognition—Self Report (MIC-SR), a measure of daily life cognitive difficulties within the domains of attention, memory, and executive functions along with measures of neuropsychological test performance, psychopathology, functioning, and quality of life. Our study found participants with and without objectively defined cognitive deficits reported self-perceived cognitive deficits of the same magnitude. No significant relationship was revealed between self-perceived and objectively measured neurocognitive deficits. Self-perceived cognitive deficits associated with attenuated psychotic symptoms, overall functioning, and quality of life, but not with adherence to, or neurocognitive benefits from, a CR intervention. Our findings indicate that UHR individuals may overestimate their cognitive difficulties, and higher levels of self-perceived cognitive deficits may relate to poor functioning. If replicated, this warrants a need for both subjective and objective cognitive assessment in at-risk populations as this may guide psychoeducational approaches and pro-functional interventions. Self-perceived cognitive impairments do not seem to directly influence CR adherence and outcome in UHR states. Further studies are needed on potential mediator between self-perceived cognitive deficits and functioning and quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis are characterized by persistent cognitive deficits within both global and specific cognitive domains1,2,3,4,5,6. Meta-analytical evidence has revealed moderate overall impairments in neurocognition in UHR compared to healthy controls (Hedges’ g = −0.344)7. Additionally, the severity of neurocognitive impairments are found to be intermediate between that of patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls3,7. Neurocognitive deficits in UHR have been implicated in psychosis development4,8 and poor functional outcome9,10.

As performance-based cognitive testing is the preferred assessment measure employed in psychosis research, few studies have elucidated on patient’s self-perceived cognitive impairments: in general, the studies do not find an association between objective and subjective neurocognitive deficits in patients with established psychosis11,12,13,14. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has, however, investigated whether this discrepancy between objective and subjective cognitive deficits also apply to the UHR state of psychosis.

Cognitive remediation is one of the most promising interventions to alleviate cognitive deficits, with proven effectiveness in first-episode and more chronic states of psychosis with small to medium effect sizes on cognitive and functional outcomes15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The existing, albeit small, literature does not indicate awareness of cognitive deficits is a pre-requisite for positive outcome of a cognitive remediation intervention in schizophrenia13,14. While considerably less studied, preliminary data indicate efficacy of cognitive remediation in the UHR state of psychosis22, but it remains, however, unclear whether self-perceived cognitive deficits may influence adherence to cognitive remediation in the UHR population. That is, whether higher levels of subjectively reported cognitive deficits will relate to UHR individuals adhering to and engaging in a cognitive remediation intervention.

By using data from the hitherto largest randomized, clinical trial (FOCUS trial)23 on cognitive remediation in the UHR population, we conducted secondary, exploratory analyses aimed at investigating the relationship between self-perceived neurocognitive deficits and objective cognitive performance, psychopathology, functioning, and adherence to a cognitive remediation intervention. The study addressed the following questions: (1) Is there a relationship between subjective and objective cognitive deficits in UHR individuals? (2) Is there an association between subjectively reported cognitive deficits and clinical symptoms and functioning/quality of life? (3) Do self-perceived cognitive deficits associate with adherence to and benefit from a cognitive remediation intervention?

Results

Out of the 73 UHR individuals randomized to the cognitive remediation interventions, 52 (71%) completed the MIC-SR. Reasons for not completing the MIC-SR were: drop-out before starting the cognitive remediation intervention (n = 8), or lack of time to complete MIC-SR (n = 13). Analyses revealed that the participants completing the MIC-SR did not differ from the ones not completing the MIC-SR on any of the demographic or clinical variables. Twenty-nine (55.8%) of the participants were females, and they had a mean age of 23.98 (SD 4.6) and an average of 14.29 (SD 2.4) years of education. The participants mainly fulfilled the high-risk criteria of APS (N = 40, 76.9 %) (demographic and baseline measures are depicted in Table 1). Of the 52 UHR participants completing the MIC-SR, 32 (61%) showed impaired objectively measured cognition, corresponding to a BACS z-score of ≤−1.35, which has been reported to indicate borderline to impaired cognition in the general population12.

The participants had a mean MIC-SR total score of 21.2 (7.6) and a MIC-SR average frequency score of 1.9 (.6) indicating that the UHR individuals reported experiencing cognitive impairments more than once a week. Participants displaying objective cognitive deficits had a mean MIC-SR total score of 19.9 (SD 7.7) and a MIC-SR average frequency score of 1.9 (SD .60). Participants not displaying cognitive deficits had a mean MIC-SR total score of 23.4 (SD 7.1) and a MIC-SR average frequency of 1.7 (SD = .6).

Participants attended an average of 10.9 (SD = 7.6) out of the total 20 sessions of neuro- and social cognitive remediation and had an average of 11.9 (SD = 16.4) h of neurocognitive training (including both group- and homebased training).

Relationship between subjective and objective cognitive deficits

The one-way ANOVA revealed that the 32 UHR individuals exhibiting objective cognitive deficits did not differ from the 20 participants not displaying objective cognitive deficits on the MIC-SR total score (p = 0.11). Neither did the Spearman’s correlational analyses reveal a significant baseline correlation between the MIC-SR total score and the BACS composite score (rho = −0.12, p = 0.39).

Additional analyses revealed that the MIC-SR total score did not significantly relate to estimated full scale IQ, verbal IQ, performance IQ, or years of education. Estimated IQ was, however, significantly related to the BACS composite score.

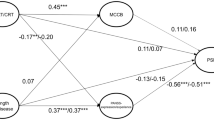

Association between self-perceived cognitive deficits and clinical symptoms, functioning and quality of life

Regression analyses revealed baseline MIC-SR to associate with the baseline measures of CAARMS composite, and the PSP and AQoL-8D, but not with negative or depressive symptoms (Table 2). That is higher scores on the self-perceived cognitive impairments measure associated with greater severity of attenuated psychotic symptoms and lower functioning. The MIC-SR explained 10%, 7% and 22% of the variance on the CAARMS, PSP and AQoL-8D, respectively.

Relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and adherence to cognitive remediation

As depicted in Table 3, no significant associations were found between the baseline MIC-SR total score and number of neurocognitive training hours, number of CR sessions attended, drop-out of therapy, or change scores on the BACS composite score pre/post-treatment.

Discussion

In keeping with previous literature in psychosis11,12,13,14 and other psychiatric disorders such as depression24 and bipolar disorder25, we did not find a significant association between subjective and objectively measured cognitive deficits in UHR individuals. This discrepancy could reflect general difficulties in self-evaluation in psychotic disorders26, or it could reflect the notion that subjectively reported, and laboratory based assessment of neuropsychological functioning may measure different aspect of cognition, with self-reported measures having greater ecological validity as they tap cognitive difficulties as the appear in the individuals daily life27,28,29. This potential of measures of subjective and objective cognitive deficits tapping different aspects of cognition is further reflected in the finding of subjective cognitive deficits being unrelated to estimated IQ, while objective cognitive deficits (BACS composite score) were significantly related. Furthermore, our study found UHR individuals to report self-perceived cognitive deficits of a magnitude exceeding that of patients with established psychosis (mean MIC-SR total score in UHR = 21/SD = 7, schizophrenia = 14.0/SD = 9.7 and 13.9/SD = 9.40)12,14. This is rather surprising as UHR individuals in general display performance-based cognitive deficits of a smaller magnitude than patients with schizophrenia7. Additionally, a little over one-third (39%) of our sample was not found to be cognitively impaired on the performance-based neurocognition measure but still reported self-perceived cognitive impairments in the same range as those with established cognitive deficits. This contrasts some studies in schizophrenia finding that a substantial number of patients do not have an awareness of cognitive deficits even in the presence of objectively measured deficits12,13,30. This discrepancy indicates that while patients with schizophrenia may underestimate their level of cognitive deficits, UHR individuals may overestimate their cognitive difficulties. Speculating, this could potentially cause UHR individuals to experience defeatist beliefs and lead to daily-life functional impairments31,32. Adding weight to this hypothesis is our cross-sectional finding of self-perceived cognitive difficulties being adversely associated with overall functioning and quality of life explaining 7% and 22% of the variance on these functioning measures, respectively. This warrants a need for future studies investigating whether potential mediators such as defeatist beliefs or perceived competence may mediate the relationship between self-perceived cognitive impairments and functional decrements. Furthermore, it suggests a need for assessing both self-perceived and actual cognitive deficits in UHR groups. In cases of discrepancy between these domains, psychoeducation on cognitive deficits and a focus on cognitive strengths and resilience, could be instituted. While this is, to our knowledge, the first study to elucidate on subjective neurocognitive deficits in a UHR population, a previous study has assessed self-perceived social cognitive impairments in a UHR sample finding a correlation between subjectively experienced cognitive deficits and decrements in role functioning33 which further supports the existence of a link between self-perceived cognitive deficits and functioning in UHR.

Regarding the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and psychopathology, we found a significant association with attenuated psychotic symptoms, but not depressive or negative symptoms. This contrast findings from patients with schizophrenia of significant associations between self-perceived and clinician-rated cognitive impairments and depressive, but not positive (or negative) symptoms12,30. These findings from schizophrenia samples have indicated that those with higher depressive scores may have greater awareness of cognitive dysfunctions which echoes reports of correlations between depressive symptoms and better insight into psychosis34. Findings are, however, mixed, as another study reported less severe depressive symptoms in schizophrenia samples with better insight into neurocognitive deficits13. Our finding of an association between self-perceived cognitive impairments and attenuated psychotic symptoms are in accordance with a previous report from a UHR sample, albeit this relationship was observed between self-perceived social cognitive deficits and attenuated psychotic symptoms33. It does, however, contrasts with the essentially weak relationship found between performance-based neurocognition and attenuated- and fully psychotic symptoms35,36,37. Hypothesizing, our finding may suggest that some UHR individuals may be inclined to perceive daily life cognitive impairments in areas such as attention, memory, and problem-solving influence level of subthreshold psychotic symptoms (which includes disorganization), or vice versa.

Lastly, this study aimed to elucidate on the relationship between baseline subjective cognitive deficits and adherence to, and benefits from, a cognitive remediation intervention in UHR. We did not find that self-perceived cognitive difficulties were significantly associated with attendance, adherence, or engagement in a cognitive remediation intervention. Neither did it significantly associate with change scores on the global neurocognitive outcome. In previous reports from patients with schizophrenia, poor insight into neurocognitive deficits has not been adversely related to cognitive remediation attendance, treatment satisfaction13, or cognitive benefits13,14, although it may impact engagement in treatment via its interaction with perceived competency, a motivational construct that promotes treatment engagement14.

While being the hitherto largest RCT on cognitive remediation in the UHR population, our study is limited by a relatively small sample completing the MIC-SR (N = 52). Furthermore, the RCT study was not designed, nor potentially adequately powered, to address the current research question, which warrants a need for future well-powered studies investigating self-perceived cognitive deficits in response to a cognitive remediation intervention in UHR states. Finally, the study enrolled adults at UHR for psychosis, and while this is similar to other large-scale UHR research studies38 the age range is somewhat older than many other UHR studies39,40,41,42,43, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the entire UHR population.

To conclude, our study extends previous findings from schizophrenia and other psychiatric populations of a lack of relationship between objectively and subjectively measured neurocognitive deficits to the population of individuals at UHR for psychosis. Also, our results suggest that UHR individuals may overestimate their level of cognitive deficits indicating this to be a target of psychoeducational approaches. Additionally, we found self-perceived cognitive deficits to associate with overall functioning and quality of life which, if replicated, point towards a target for pro-functional intervention approaches. Future research would benefit from investigating whether psychological aspects such as defeatist beliefs and perceived competence could serve as potential mediator between self-perceived cognitive deficits and functional outcome and benefits from a cognitive remediation intervention in UHR. Finally, we did not find baseline self-perceived cognitive deficits to relate to engagement in- or outcome of cognitive remediation in UHR indicating that subjectively experienced cognitive deficits do not seem to constitute a suitable clinical selection-based criterion of whether individuals should be offered a cognitive remediation intervention.

Methods

Study design

A detailed description of the original study can be found in ref. 44. Briefly described, participants were recruited to the randomized clinical, FOCUS trial from the psychiatric in- and outpatient facilities in the greater catchment area of Copenhagen, Denmark from April 2014 to December 2017. On completion of baseline assessments, the participants were randomly assigned to either 20-weeks of cognitive remediation as an add on to treatment as usual (TAU + CR) or to treatment as usual (TAU). The cognitive remediation intervention comprised 2 h of group training (1 h of neurocognitive training, with subsequent 15 min of bridging session, and 1 h of social cognitive training) once a week for a total of 20 weeks. The cognitive remediation targeted both neuro- and social-cognition using the manualized, evidence-based treatments; the Neuropsychological Educational Approach to Cognitive Remediation (NEAR)45 and the Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) manual46. Supplementary to the group training, the participants received 12 individual sessions to personalize and maximize the transfer of the effect of the cognitive training to the participants’ daily lives. In addition, participants were encouraged to conduct a minimum of 1-h weekly of home-based neurocognitive training. The neurocognitive training was scaled to comprise 40 h of neurocognitive remediation, expecting that each participant attended the 20-group sessions and did the recommended 1-h weekly of home-based training.

The study protocol was approved by the Committee on Health Research Ethics of the Capital Region Denmark (study: H-6-2013-015). All participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. Trial registration ClinicalTrial.gov identifier: NCT02098408.

Participants

The sample consisted of 146 help-seeking individuals aged 18–40 years, who met one or more UHR criteria according to the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States47: attenuated psychotic symptom group; brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms group; and/or trait and vulnerability group along with a significant drop in functioning or sustained low functioning for the past year.

Assessments

The demographic information assessed in the study comprised age, years of education, and estimation of current IQ, with the latter assessed using four subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Third Edition (WAIS-III)48: Vocabulary, Similarities, Block Design, and Matrix Reasoning.

Self-perceived cognitive deficits

The Measure of Insight into Cognition—Self Report (MIC-SR)12,49 was used to assess self-perceived cognitive impairments. The MIC-SR comprises 12 items on daily life difficulties with memory, attention, and problem solving. Each of the 12 items are given a score of 0–3 corresponding to experiencing cognitive difficulties “never” (0), “once a week or less” (1), “twice a week” (2), or “almost daily” (3). A total score can be extracted summing the ranges from 0 to 36. An average frequency score can be computed dividing the total score by 12. The MIC-SR has proven reliability and validity in patients with schizophrenia49.

Performance-based cognitive performance

Performance-based cognition was indexed with the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) battery50. The BACS composite score derives from six subtests of the domains of verbal learning and memory, speed of processing and executive functions.

Clinical symptoms and functioning

Symptoms were assessed with three instruments; the CAARMS, providing a level of attenuated psychotic symptom, by weighing the intensity of symptom scores by their frequency to form a CAARMS composite score51,52; the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)53 yielding the level of negative symptoms using the SANS global score; and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)54 yielding level of depressive symptoms. Functioning was measured with two instruments capturing different aspects of functioning: Overall functioning was measured using the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP)55. This is a composite measure of functioning in the areas of occupational functioning, social functioning, and self-care. Subjective quality of life was reported with the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL-8D)56. The clinical assessors were all psychologists and medical doctors, that had received extensive training in using the instruments and conducted regular inter-rater reliability ratings on selected outcomes. Cognitive tests were conducted by psychologist students that had received comprehensive training and were supervised regularly by a senior psychologist.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0. Baseline descriptive statistics were reported by means and standard deviations. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the group displaying performance-based cognitive deficits with the group that did not on the MIC-SR. Stratification of the sample was based on whether or not the participants displayed a BACS composite score of ≤−1.35, as previous findings indicate this to be a relevant cut-off to determine borderline to impaired cognition12. Univariate linear regression analyses were run to investigate the association between the dependent variable of MIC-SR and the independent variables of clinical symptoms (CAARMS, SANS, MADRS) and functioning (PSP and AQoL-8D). Bivariate correlations, using a Spearman’s correlation coefficient with a two-tailed significance test, were run to investigate the correlations between MIC-SR total score and BACS composite score at baseline and as difference score pre/post-treatment along with indices of adherence to the cognitive remediation intervention. Significance levels were set to p < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hawkins, K. A. et al. Neuropsychological status of subjects at high risk for a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 67, 115–122 (2004).

Niendam, T. A. et al. Neurocognitive performance and functional disability in the psychosis prodrome. Schizophr. Res. 84, 100–111 (2006).

Brewer, W. J. et al. Generalized and specific cognitive performance in clinical high-risk cohorts: a review highlighting potential vulnerability markers for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 32, 538–555 (2005).

Bolt, L. K. et al. Neurocognition as a predictor of transition to psychotic disorder and functional outcomes in ultra-high risk participants: Findings from the NEURAPRO randomized clinical trial. Schizophr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018 (2018).

Giuliano, A. J. et al. Neurocognition in the psychosis risk syndrome: a quantitative and qualitative review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 399–415 (2012).

Seidman, L., Giuliano, A. & Walker, E. Neuropsychology of the Prodrome to Psychosis in the NAPLS Consortium. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 578–588 (2010).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 562–571 (2012).

Seidman, L. J. et al. Association of neurocognition with transition to psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 73, 1239–1248 (2016).

Carrión, R. E. et al. Prediction of functional outcome in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 1133 (2013).

Meyer, E. C. et al. The relationship of neurocognition and negative symptoms to social and role functioning over time in individuals at clinical high risk in the first phase of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 1452–1461 (2014).

Moritz, S., Ferahli, S. & Naber, D. Memory and attention performance in psychiatric patients: Lack of correspondence between clinician-rated and patient-rated functioning with neuropsychological test results. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 10, 623–633 (2004).

Medalia, A., Thysen, J. & Freilich, B. Do people with schizophrenia who have objective cognitive impairment identify cognitive deficits on a self report measure? Schizophr. Res. 105, 156–164 (2008).

Burton, C. Z. & Twamley, E. W. Neurocognitive insight, treatment utilization, and cognitive training outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 161, 399–402 (2015).

Saperstein, A. M., Lynch, D. A., Qian, M. & Medalia, A. How does awareness of cognitive impairment impact motivation and treatment outcomes during cognitive remediation for schizophrenia? Schizophr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.02.014 (2020).

Mcgurk, S., Twamley, E., Sitzer, D., Mchugo, G. & Mueser, K. Analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1791–1802 (2007).

Krabbendam, L. & Aleman, A. Cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia: A quantitative analysis of controlled studies. Psychopharmacology 169, 376–382 (2003).

Kurtz, M. M., Moberg, P. J., Gur, R. C. & Gur, R. E. Approaches to cognitive remediation of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 11, 197–210 (2001).

Twamley, E. W., Jeste, D. V. & Bellack, A. S. A review of cognitive training in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 29, 359–382 (2003).

Grynszpan, O. et al. Efficacy and specificity of computer-assisted cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: a meta-analytical study. Psychol. Med. 41, 163–173 (2011).

Pilling, S. et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: II. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of social skills training and cognitive remediation. Psychol. Med. 32, 783–791 (2002).

Wykes, T., Huddy, V., Cellard, C., McGurk, S. R. & Czobor, P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: Methodology and effect sizes. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 472–485 (2011).

Glenthøj, L. B., Hjorthøj, C., Kristensen, T. D., Davidson, C. A. & Nordentoft, M. The effect of cognitive remediation in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a systematic review. npj Schizophr. 3, 20 (2017).

Glenthøj, L. B. et al. Effectiveness of cognitive remediation in the ultra-high risk state for psychosis. World Psychiatry. 19, 401–402 (2020).

Mohn, C. & Rund, B. R. Neurocognitive profile in major depressive disorders: relationship to symptom level and subjective memory complaints. BMC Psychiatry 16, 1–6 (2016).

Miskowiak, K. W. et al. Predictors of the discrepancy between objective and subjective cognition in bipolar disorder: a novel methodology. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 134, 511–521 (2016).

Gould, F. et al. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: accuracy of evaluation of cognition and everyday functioning. Neuropsychology. 29, 675–682 (2015).

Van der Elst, W., Van Boxtel, M. P. J., Van Breukelen, G. J. P. & Jolles, J. A large-scale cross-sectional and longitudinal study into the ecological validity of neuropsychological test measures in neurologically intact people. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 23, 787–800 (2008).

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Kenworthy, L. & Barton, R. M. Profiles of everyday executive function in acquired and developmental disorders. Child Neuropsychol. 8, 121–137 (2003).

Burgess, P. Theory and methodology in executive function and research. in Methodology of frontal and executive function (ed. P. Rabbitt), 81–116 (Psychology Press., Hove, 1997).

Medalia, A. & Thysen, J. Insight into neurocognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 1221–1230 (2008).

Perivoliotis, D., Morrison, A. P., Grant, P. M., French, P. & Beck, A. T. Negative performance beliefs and negative symptoms in individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis: a preliminary study. Psychopathology 42, 375–379 (2009).

Campellone, T. R., Sanchez, A. H. & Kring, A. M. Defeatist performance beliefs, negative symptoms, and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr. Bull. 42, 1343–1352 (2016).

Pelizza, L. et al. Subjective experience of social cognition in adolescents at ultra-high risk of psychosis: findings from a 24-month follow-up study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01482-y (2020).

Crumlish, N. et al. Early insight predicts depression and attempted suicide after 4 years in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 112, 449–455 (2005).

Addington, J., Saeedi, H. & Addington, D. The course of cognitive functioning in first episode psychosis: changes over time and impact on outcome. Schizophr. Res. 78, 35–43 (2005).

Ventura, J., Hellemann, G. S., Thames, A. D., Koellner, V. & Nuechterlein, K. H. Symptoms as mediators of the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 113, 189–199 (2009).

Cornblatt, B. A. et al. The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Schizophr. Bull. 29, 633–651 (2003).

McGorry, P. D. et al. Effect of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in young people at ultrahigh risk for psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 19 (2017).

Addington, J. et al. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS 2): overview and recruitment. Schizophr. Res. 142, 77–82 (2012).

Yung, A. R. et al. PACE: a specialised service for young people at risk of psychotic disorders. Med. J. Aust. 187, 43–46 (2007).

Ising, H. K. et al. Four-year follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy in persons at ultra-high risk for developing psychosis: The Dutch Early Detection Intervention Evaluation (EDIE-NL) Trial. Schizophr. Bull. 42, 1243–1252 (2016).

Nelson, B. et al. Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (‘Prodromal’) for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 793 (2013).

Fusar-Poli, P., Byrne, M., Badger, S., Valmaggia, L. R. & McGuire, P. K. Outreach and support in South London (OASIS), 2001-2011: ten years of early diagnosis and treatment for young individuals at high clinical risk for psychosis. Eur. Psychiatry 28, 315–326 (2013).

Glenthøj, L. B. et al. The FOCUS trial: cognitive remediation plus standard treatment versus standard treatment for patients at ultra-high risk for psychosis: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 16, 25 (2015).

Medalia, A. & Freilich, B. The Neuropsychological Educational Approach to Cognitive Remediation (NEAR) Model: practice principles and outcome studies. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 11, 123–143 (2008).

Roberts, D. L., David, P. & Combs, D. R. Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT): Group Psychotherapy for Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders, Clinician Guide. (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Yung, A. R. et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 39, 964–971 (2005).

Wechsler, D. WAIS-III administration and scoring manual. (The Psychological Corporation, 1997).

Saperstein, A. M., Thysen, J. & Medalia, A. The Measure of Insight into Cognition: Reliability and validity of clinician-rated and self-report scales of neurocognitive insight for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 134, 54–58 (2012).

Keefe, R. S. E. et al. The brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr. Res. 68, 283–297 (2004).

Morrison, A. P. et al. Early detection and intervention evaluation for people at risk of psychosis: multisite randomised controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 344, e2233 (2012).

Lim, J. et al. Impact of psychiatric comorbidity in individuals at Ultra High Risk of psychosis—findings from the Longitudinal Youth at Risk Study (LYRIKS). Schizophr. Res. 164, 8–14 (2015).

Andreasen, N. C. Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms. (Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, the University of Iowa, 1984).

Montgomery, S. A. & Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 134, 382–389 (1979).

Morosini, P. L., Magliano, L., Brambilla, L., Ugolini, S. & Pioli, R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 101, 323–329 (2000).

Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., Khan, M. A. & Maxwell, A. Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient 7, 85–96 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The study has been funded through The Danish Council for Independent Research (grant number DFF-4004-00314); TrygFonden (grant number ID 108119); the Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark; the research fund of the Capital Region of Denmark; the Lundbeck Foundation Center for Clinical Intervention and Neuropsychiatric Schizophrenia Research, CINS (grant number R155-2013-16337). The funding source had no role in any aspect of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B.G. and M.N. conceived the study. L.B.G., L.M., T.D.K., and C.W. performed the data acquisition. L.B.G. and A.M. interpreted the data. L.B.G. wrote the paper. All authors approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glenthøj, L.B., Mariegaard, L., Kristensen, T.D. et al. Self-perceived cognitive impairments in psychosis ultra-high risk individuals: associations with objective cognitive deficits and functioning. npj Schizophr 6, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-020-00124-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-020-00124-1

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

-

Investigation of social and cognitive predictors in non-transition ultra-high-risk’ individuals for psychosis using spiking neural networks

Schizophrenia (2023)

-

A randomized controlled trial of Goal Management Training for executive functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders or psychosis risk syndromes

BMC Psychiatry (2022)