Abstract

Electrons and holes can spontaneously form excitons and condense in a semimetal or semiconductor, as predicted decades ago. This type of Bose condensation can happen at much higher temperatures in comparison with dilute atomic gases. Two-dimensional (2D) materials with reduced Coulomb screening around the Fermi level are promising for realizing such a system. Here we report a change in the band structure accompanied by a phase transition at about 180 K in single-layer ZrTe2 based on angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) measurements. Below the transition temperature, gap opening and development of an ultra-flat band top around the zone center are observed. This gap and the phase transition are rapidly suppressed with extra carrier densities introduced by adding more layers or dopants on the surface. The results suggest the formation of an excitonic insulating ground state in single-layer ZrTe2, and the findings are rationalized by first-principles calculations and a self-consistent mean-field theory. Our study provides evidence for exciton condensation in a 2D semimetal and demonstrates strong dimensionality effects on the formation of intrinsic bound electron–hole pairs in solids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excitons in solids, bound states between an electron and a hole, were predicted to condense under appropriate conditions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Because of their small effective masses, such condensation can occur at high temperatures9,10, which is of great interest in modern condensed matter research. Although the condensed phases of excitons have been realized in cases involving optical pumping, quantum Hall states in a magnetic field, and electrical generation in atomic double-layer heterostructures9,10,11,12,13,14, very few examples were identified in which the long-range excitonic order is spontaneously formed at low temperatures under equilibrium conditions. Realization of such a system is difficult because it needs a delicate balance among several factors: the size of the band gap, the binding energy of the electron–hole pairs, and the screening strength5,7. Promising candidates so far include TmSe0.45Te0.55 under pressure, Ta2NiSe5, 1T-TiSe2, and other proposed candidates15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. It is still under intense debate whether the phase transition in Ta2NiSe5 is driven by an exciton condensation or the lattice distortion from a change of the structure22,23,27,28, and various competing interpretations have been offered for bulk TiSe218,20. Thus far, experimental observation of spontaneous exciton condensation remains inconclusive.

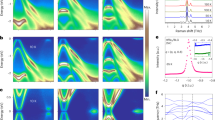

Exciton condensation in materials has been predicted to lead to a new insulating ground state, an excitonic insulator4,5,6,7,8. General features related to the phase transition include the mixing of conduction and valence bands and gap opening around the Fermi level (EF). The band structure is renormalized and exhibits a characteristic flat valence band top (Fig. 1)29. These signatures should be readily captured by ARPES. Transition metal dichalcogenides with vanishing indirect band gap or band overlap between the valence and conduction bands are promising candidates for developing 2D excitonic insulators4,5,6,7. These layered materials can be easily prepared as single layers, and single-layer TiSe2 appears to be a natural choice. However, the semimetal-insulator transition and a flat valence band top have not been observed30. Another strong candidate is ZrTe2; in bulk form, it is a metal/semimetal with a negative band gap of about −0.5 eV31,32. The Coulomb interaction between electrons and holes is strongly screened by the many carriers around the metallic Fermi surfaces, and no exciton condensation is expected or observed. This unfavorable condition is, however, completely reversed for the single layer, for which the gap is almost zero, and electronic screening is largely suppressed in the 2D limit26,33.

a Atomic structure of single-layer ZrTe2. b Corresponding 2D Brillouin zone. c A RHEED pattern of single-layer ZrTe2 film taken at room temperature. d Core-level photoemission spectra taken with 100 eV photons. e Schematic diagram for evolution of the band structure and the opening of a gap from a semimetal during the exciton condensation. f ARPES maps along \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) taken with s polarized light for the normal phase at 300 K and the condensed phase at 10 K.

Results

Electronic band structure of single-layer ZrTe2

Here we study the band structures of single-layer ZrTe2 and present experimental evidence of high-temperature exciton condensation. The structure of single-layer ZrTe2 (Fig. 1a) in the normal phase consists of a triangular planar net of Zr atoms sandwiched between two Te atomic layers. Sharp reflection high-energy electron diffraction (RHEED) patterns (Fig. 1c) reveal a high-quality and well-ordered single layer of ZrTe2 grown by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) on a bilayer-graphene-terminated SiC substrate. Angle-integrated core-level scans (Fig. 1d) show the characteristic peaks of Zr and Te for the 1T phase31. Figure 1f shows ARPES maps taken with s polarized light along the \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) direction. Two hole-like valence bands are seen centered at the \(\overline{\Gamma }\) point. A previous study of single-layer ZrTe2 grown on InAs (111) shows a similar band structure, but with an upward shift of the Fermi level. The difference suggests a charge transfer from the InAs substrate32. For our sample at 300 K, the conduction band edge at the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point reaches just around the Fermi level. With the valence band edge just slightly above the Fermi level, the system is metallic. The indirect band overlap around the Fermi level is only about −0.06 eV (Supplementary Fig. 2), much smaller than the bulk case. A small band overlap implicates a small carrier density around the Fermi level, which is favorable for the formation of excitons.

Upon cooling to low temperatures, the topmost valence band develops a dispersionless (flat) top around the zone center in a range of ~±0.072 Å−1(Fig. 1f). The downward shift of the band top results in a gap of 97 meV from the Fermi level at the zone center at 10 K. This strong band renormalization is consistent with the excitonic insulator scenario that excitons consist of holes in the valence band and electrons in the conduction band condense naturally in single-layer ZrTe2. The flat band dispersions correspond to a zero group velocity for the electrons and holes in the condensed state. As seen in Fig. 2a, the flat valence band top at 10 K becomes much weaker in spectra taken with p polarized light. Another relevant feature of exciton formation is the hybridization of valence and conduction bands, which gives rise to strong folded valence bands, as observed around the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point at 10 K (Fig. 2a).

a ARPES spectra taken with p polarized light along \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) direction at 300 K and 10 K. The data at 10 K shows the gap opening and folded bands around the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point. b Calculated spectral functions of single-layer ZrTe2 in the normal and condensed phases. The mean-field solutions of the model in the condensed phase are shown as red dashed curves.

Excitonic insulator model

These observations can be understood in terms of an excitonic phase based on a BCS-like model6. Calculated spectral functions for the valence and conduction bands along \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) are shown in Fig. 2b. The results for the normal phase reproduce the essential features of the ARPES data including the spin-orbit splitting of the two valence bands. For the condensed phase, a mean-field self-consistent excitonic order parameter ∆X is included in the calculation to account for, to first order, the hybridization of conduction and valence bands. The main effects are to flatten the valence band top and to open a gap of 74 meV, both in agreement with the ARPES results. The flat valence band top around the zone center gets folded to the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point with considerable spectral weight transfer, which indicates a strong electronic nature of the phase transition19.

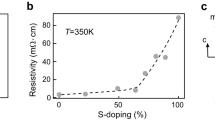

Temperature dependence of the energy gap

Systematic scans of the bands along \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) (Fig. 3a) as a function of temperature reveal details of the development of the flat band feature, the opening of the gap, and the intensity variation of the folded bands in connection with the semimetal-insulator transition. The gap formation is illustrated by the symmetrized ARPES maps in Fig. 3b. The symmetrized energy distribution curves (EDCs) at the zone center at various temperatures are shown in Fig. 3c. At high temperatures, a single peak at the Fermi level at EF indicates that the valence band top crosses over EF. At lower temperatures, this single peak bifurcates, indicating the opening of a gap. The energy gap, determined from the difference between the valence band top and the conduction band bottom, is 75 meV at 10 K. The square of the extracted energy gap is plotted as a function of temperature in Fig. 3d. Fitting to a BCS mean-field equation34 (red curve in Fig. 3d) yields a transition temperature of TC = 180 ± 6 K.

a ARPES spectra along \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\,\) reveal the development of the flat valence band top and it shifts away from the Fermi level when the temperature is decreased from 300 to 10 K. The data were taken with 40 eV photons. b ARPES maps symmetrized in energy about the Fermi level show a gap in the condensed phase. c Symmetrized EDCs at the zone center at selected temperatures between 10 and 300 K. By symmetrization, the effect of Fermi–Dirac distribution at high temperatures can be canceled out. An example of the fit to a phenomenological BCS-type function34 is shown as a red dashed curve for the EDC obtained at 10 K. d The extracted temperature dependence of the square of the energy gap. The red curve is a fit using a BCS-type mean-field equation. Transition temperature TC is labeled. The error bar is deduced from the standard deviation of the fitting.

Charge density wave (CDW) order

The nature of the phase transition is complicated by the possibility of a Peierls-type CDW transition driven by lattice instability, as opposed to an excitonic transition driven by electron–hole interaction. We performed first-principles calculations for a (\(2\times 2\)) superstructure to check the effects of lattice instability (Supplementary Fig. 6). The calculated total energy per chemical unit is lower by just 0.4 meV for the (\(2\times 2\)) phase relative to the normal phase for single-layer ZrTe2. This is much smaller than the corresponding energy lowering of 5 meV for the (\(2\times 2\)) CDW in single-layer TiSe230. The anharmonic well potential indicates intrinsic lattice instability in TiSe2, whereas the effect is not obvious in ZrTe2 (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Calculated atomic displacements in the CDW phase show δZr is 0.7% of the lattice constant (0.028 Å) and δTe is 0.3% of the lattice constant. As a comparison, the amplitude of δTi is 2.5% of the lattice constant (0.088 Å) in the single-layer TiSe2 in the CDW phase30,35. Although an imaginary phonon mode is found for single-layer ZrTe2 at the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point, the PBE band structure shows no gap opening, indicating a weak lattice instability compared to the other known CDW cases (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 10).

To estimate how large the lattice distortion is necessary to open a gap of 75 meV observed by ARPES, we imposed various amounts of lattice distortion (represented by δZr) in calculations and the obtained value is ~3.15% of the lattice constant, 4.5 times of the optimized CDW structure. Hubbard U = 6 eV were further included to account for the electron localization and the gap remains closed in the CDW phase where δZr = 0.7% of the lattice constant. (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d). These findings indicate the insufficient ability of the lattice distortion to open a significant gap in this system, although it may contribute to the formation of the backfolded bands at the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) points as in the case of single-layer TiTe2 (δTi = 1.0% of the lattice constant)36. Effects of electron–hole hybridization can be better described using the HSE functional instead of the PBE in the calculation. Similar to the mean-field self-consistent method mentioned above, HSE calculations yield a gap of ~10 meV near the \(\overline{\Gamma }\) point, indicating the necessity of the electron–hole interaction in this system. Of note is that DFT results predict a much larger overlap between the valence band top and the conduction band bottom than the experiment in the normal phase. The absolute value of the quantity predicted by the calculations may not be accurate due to the inherent limitations of the DFT method. However, the relative comparison between TiSe2 and ZrTe2 should remain valid.

The structural distortion in a single-layer film can be revealed by low-energy electron diffraction (LEED). The elastic scattering of the incident electrons with the crystal potential mostly comes from the core electrons and nuclei of crystals37. LEED patterns of single-layer TiSe2 show the 1/2 order diffraction spots corresponding to the (\(2\times 2\)) CDW phase at low temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). However, no CDW diffraction spots were observed for single-layer ZrTe2 in the probed beam energy range (20–200 eV), indicating the small lattice distortion in the CDW phase. Consistent results were obtained for different batches of samples. As a first-order approximation, the proportion of CDW spot intensity (ICDW) to the corresponding Bragg spot intensity (IBragg) is proportional to the square of the atomic displacements (μ) in the CDW phase38. With background intensity subtracted, ICDW/IBragg for single-layer TiSe2 is ~0.3. The noise level divided by the saturated intensity is used to establish the detection limit and the value is ~0.05, indicating μZrTe2 should be less than 2/5 of μTiSe2 on average (Supplementary Fig. 9c–e), in consistent with the above prediction that μZrTe2 ~ μTiSe2/3. Evidently, our LEED results set the upper bound of the atomic displacement of single-layer ZrTe2 in the CDW phase and the phase transition in this material cannot be described in terms of the usual Peierls-type CDW.

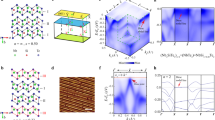

Dimensionality and carrier screening effect

Since no exciton condensation occurs in bulk ZrTe2, an interesting question is how such a transition evolves with the sample thickness from the 2D limit of a single layer to the bulk limit. ARPES spectra for N = 1, 2, 2.5 trilayer (TL) ZrTe2 taken with the unpolarized light from a He-discharge lamp along the \(\overline{\Gamma {{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) direction are presented in Fig. 4 (the N = 2.5 case represents a mixture of N = 2 and 3). The measured dispersion relations at 300 K and the multiplication of bands as N increases are in excellent agreement with theoretical results for the normal phase. All cases are metallic in the normal phase, with bands crossing the Fermi level. However, only the 1 TL sample shows gap opening and valence band folding at 10 K. Thus, the excitonic phase in the single layer is suppressed by adding just one TL. This suppression can be attributed to changes in the carrier density, which can be extracted from the Luttinger area of the Fermi surface39. The carrier density around the \(\overline{{{{{{\rm{M}}}}}}}\) point for a 2 TL film is ~4.8 × 1013/cm2, which is 136% larger than the 1 TL case. The extra carrier density leads to a stronger screening between the electrons and holes, thus hampering the formation of the excitons. A very weak CDW order may still exist in multilayer films40, but it does not lead to an excitonic phase.

To further explore the effects of carrier screening, we have employed in situ surface doping of K on the 1 TL sample (Supplementary Fig. 1a). With the sample at 10 K, increasing amounts of K doping cause the valence band top to move upward and poke through EF at a critical carrier density of 3.8 × 1013/cm2. The folded valence bands also disappear at this critical doping level. The lower valence band, separated by spin-orbit splitting from the top valence band, also shifts up slightly upon initial K doping. However, further increasing the doping level beyond the critical value causes it to shift downward together with the conduction band. Thus, the overall movements of the bands cannot be described by a simple rigid shift of all bands, other effects like atom intercalation can renormalize the band structure41. An implication is that electron doping leads to the suppression of the bound electron–hole pairs; beyond the critical doping level, the gapped ground state is destroyed, and the system returns to a normal semimetallic state.

The total evidence based on both experiment and theory suggests that single-layer ZrTe2 is a prototypical 2D excitonic matter. A strong interband electron–hole coherent coupling in 2D and poor electronic screening by a low carrier density around the Fermi level conspire to make this system a unique case to display the requisite flat bands for excitonic condensation. The results are relevant to the development of a comprehensive understanding of the physics of exciton condensation in solids. The high transition temperature in this case suggests a versatile platform for experimentation in quantum effects and phenomena based on exciton coherence.

Methods

ARPES measurements

ZrTe2 thin films were grown in situ in the integrated MBE/ARPES systems at the laboratory at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, beamlines 10.0.1 at Advanced Light Sources in Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and beamline 13U at National Synchrotron Radiation Lab in Hefei. Samples were transferred via a vacuum suitcase to beamline 03U at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility42. Substrates of 4H-SiC were flash-annealed for multiple cycles to form a well-ordered bilayer graphene on the surface. Single-layer and multilayer ZrTe2 were grown on top of the substrate by co-evaporating high-purity Zr and Te from an electron-beam evaporator and a Knudsen effusion cell, respectively, while the substrate was maintained at 600 °C. The growth process and thickness of the films were monitored by RHEED, and the growth rate was set to 60 min per layer of ZrTe2. The formation of the multilayer of ZrTe2 is also evidenced by the evolution of the band structure measured by ARPES. ARPES measurements were performed at a base pressure of ~5 × 10−11 mbar with an in-laboratory He-discharge lamp (He-I 21.2 eV) and 16–100 eV photons at synchrotron using Scienta DA30 analyzers. The energy resolution is better than 15 meV and the angular resolution is around 0.2°. Each sample’s crystallographic orientation was precisely determined from the symmetry of constant-energy-contour ARPES maps.

Computational details of density functional theory from first principles

Calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio package (VASP)43,44 with the projector augmented wave method45,46. A plane-wave energy cutoff of 520 eV and a \(24\times 24\times 1\) k-mesh were employed. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional47 was used for structure optimization of the single-layer ZrTe2. Freestanding films were modeled with a 16-Å vacuum gap between adjacent layers in the supercell. The fully optimized in-plane lattice constant for a single-layer 1T-ZrTe2 is a = 3.974 Å. Since PBE functional is known to underestimate band gap, HSE functional48 was also employed to better capture electron–hole hybridizations. For the 2 TL and 3 TL, the PBEsol functional49 was used to relax interlayer distance; the in-plane lattice constant was taken from the monolayer results. Spin-orbit couplings are included in the calculations. Phonon calculations were carried out using the supercell method as implemented in the Phonopy package50. The band unfolding was performed using the BandUP code51,52.

Self-consistent mean-field theory

We study the excitonic insulator phase based on the mean-field calculation of an 11-band model. The noninteracting part of the model Hamiltonian was constructed from wannierized orbitals53 of first-principle HSE calculations. \({{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}}}^{0}=\sum {{{{{{\rm{\epsilon }}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{nk}}}}}}}{c}_{{nk}}^{{{\dagger}} }\,{c}_{{nk}}\). We consider interactions between two topmost valence bands and two lowest conduction bands. The interaction part of the Hamiltonian reads

where \(N\) is the number of k-points in the Brillouin zone (BZ). We assume that the interaction does not depend on band indices and crystal momentum \(k\) and \({k}^{{\prime}}\) and takes the form of screened Coulomb interaction \({{{{{\rm{V}}}}}}\left({{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}\right)=\frac{{{{{{\rm{U}}}}}}{{\tanh }}\frac{\xi q}{2}}{{{{{{\rm{\xi }}}}}}{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}/2},\)24 where \({{{{{\rm{\xi }}}}}}\) is set to 25 nm and U is a tuning parameter. To solve the excitonic insulator state, we consider a set of order parameters of electron–hole coherence \({\Delta }_{X}({{{{{\bf{Q}}}}}})=\frac{1}{N}{\sum }_{{{{{{\rm{k}}}}}}}\langle {c}_{{ck}}^{{{\dagger}} }{c}_{{vk}+Q}\rangle\) with wavevectors \({{{{{\bf{Q}}}}}}={{{{{{\bf{b}}}}}}}_{1}/2\), \(-{{{{{{\bf{b}}}}}}}_{2}/2\), and \(({{{{{{\bf{b}}}}}}}_{2}-{{{{{{\bf{b}}}}}}}_{1})/2\), where \({{{{{{\bf{b}}}}}}}_{1}\) and \({{{{{{\bf{b}}}}}}}_{2}\) are two in-plane reciprocal lattice vectors. These wavevectors correspond to the triple-q CDW states observed in the experiment40.

We numerically solved the Hamiltonian in a folded BZ with a uniform sampling of 48 × 48 k-grid in the BZ. A k-point in the full BZ is labeled by a corresponding k-point in the folded BZ and a wave vector connecting them. We found that with a parameter \({{{{{\rm{U}}}}}}=65\), the result agrees well with the experiment. The self-consistent calculation is initialized with a nonzero order parameter then the mean-field Hamiltonian is diagonalized. From the eigenvectors, we can compute the new order parameters and repeat the procedure until convergence. The spectral function is computed following ref. 54. We have

where \({{{{{{\rm{E}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{nk}}}}}}}\) and \({{{{{{\rm{\varphi }}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{nk}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{j}}}}}},{{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}_{0}}\) are the n-th eigenenergy and eigenfunctions of the mean-field Hamiltonian with momentum k, respectively, j is the index of the bare band and \({{{{{{\rm{q}}}}}}}_{0}=0\) labels components from the folded BZ centered at \(\overline{\Gamma }\) since the momentum k in the spectral functions is defined in the unfolded zone.

Data availability

General methods, experimental procedures, and characterizations are available within the article and the Supplementary Information. Other relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pitaevskii, L. & Stringari, S. Bose-Einstein Condensation (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Leggett, A. J. Quantum liquids. Science 319, 1203–1205 (2008).

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. & Schrieffer, J. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

Mott, N. F. The transition to the metallic state. Philos. Mag. 6, 287–309 (1961).

Keldysh, L. V. & Kopaev, Y. V. Possible instability of semimetallic state toward Coulomb interaction. Sov. Phys. Solid State 6, 2219–2224 (1965).

Jérome, D., Rice, T. M. & Kohn, W. Excitonic insulator. Phys. Rev. 158, 462 (1967).

Halperin, B. I. & Rice, T. M. Possible anomalies at a semimetal-semiconductor transition. Rev. Mod. Phys. 40, 755–766 (1968).

Kohn, W. Excitonic phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 19, 439 (1967).

Snoke, D. Spontaneous Bose coherence of excitons and polaritons. Science 298, 1368–1372 (2002).

Eisenstein, J. P. & MacDonald, A. H. Bose-Einstein condensation of excitons in bilayer electron systems. Nature 432, 691–694 (2004).

Unuchek, D. et al. Room-temperature electrical control of exciton flux in a van der waals heterostructure. Nature 560, 340–344 (2018).

Jauregui, L. A. et al. Electrical control of interlayer exciton dynamics in atomically thin heterostructures. Science 366, 870–875 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Evidence of high-temperature exciton condensation in two-dimensional atomic double layers. Nature 574, 76–80 (2019).

Ma, L. et al. Strongly correlated excitonic insulator in atomic double layers. Nature 598, 585–589 (2021).

Wachter, P., Bucher, B. & Malar, J. Possibility of a superfluid phase in a Bose condensed excitonic state. Phys. Rev. B 69, 094502 (2004).

Wakisaka, Y. et al. Excitonic insulator state in Ta2NiSe5 probed by photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 026402 (2009).

Kim, K. et al. Direct observation of excitonic instability in Ta2NiSe5. Nat. Commun. 12, 1969 (2021).

Kogar, A. et al. Signatures of exciton condensation in a transition metal dichalcogenide. Science 358, 1314–1317 (2017).

Cercellier, H. et al. Evidence for an excitonic insulator phase in 1T-TiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 146403 (2007).

Holt, M. et al. X-ray studies of phonon softening in TiSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3799–3802 (2001).

Fukutani, K. et al. Electrical tuning of the excitonic insulator ground state of Ta2NiSe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 206401 (2019).

Mazza, G. et al. Nature of symmetry breaking at the excitonic insulator transition: Ta2NiSe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 197601 (2020).

Windgätter, M. et al. Common microscopic origin of the phase transitions in Ta2NiS5 and the excitonic insulator candidate Ta2NiSe5. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 210 (2021).

Jia, Y. et al. Evidence for a monolayer excitonic insulator. Nat. Phys. 18, 87–93 (2022).

Sun, B. et al. Evidence for equilibrium exciton condensation in monolayer WTe2. Nat. Phys. 18, 94–99 (2022).

Varsano, D., Palummo, M., Molinari, E. & Rontani, M. A monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenide as a topological excitonic insulator. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 367–372 (2020).

Lu, H. et al. Evolution of the electronic structure in Ta2NiSe5 across the structural transition revealed by resonant inelastic x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 103, 235159 (2021).

Watson, M. D. et al. Band hybridization at the semimetal-semiconductor transition of Ta2NiSe5 enabled by mirror-symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013236s (2020).

Ataei, S. S., Varsano, D., Molinari, E. & Rontani, M. Evidence of ideal excitonic insulator in bulk MoS2 under pressure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, 13 (2021).

Chen, P. et al. Charge density wave transition in single-layer titanium diselenide. Nat. Commun. 6, 8943 (2015).

Kar, I. et al. Metal-chalcogen bond-length induced electronic phase transition from semiconductor to topological semimetal in ZrX2 (X = Se and Te). Phys. Rev. B 101, 165122 (2020).

Tsipas, P. et al. Massless Dirac fermions in ZrTe2 semimetal grown on InAs(111) by van der Waals epitaxy. ACS Nano 12, 1696–1703 (2018).

Xi, X. et al. Strongly enhanced charge-density-wave order in monolayer NbSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 765–769 (2015).

Norman, M. R., Randeria, M., Ding, H. & Campuzano, J. C. Phenomenology of the low-energy spectral function in high-TC superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 57, R11093 (1998).

Fang, X.-Y., Hong, H., Chen, P. & Chiang, T.-C. X-ray study of the charge-density-wave transition in single-layer TiSe2. Phys. Rev. B 95, 201409(R) (2017).

Chen, P. et al. Emergence of charge density waves and a pseudogap in single-layer TiTe2. Nat. Commun. 8, 516 (2017).

Jona, F., Strozier, J. A. Jr & Yang, W. S. Low-energy electron diffraction for surface structure analysis. Rep. Prog. Phys. 45, 527 (1982).

Storeck, G. et al. Structural dynamics of incommensurate charge-density waves tracked by ultrafast low-energy electron diffraction. Struct. Dyn. 7, 034304 (2020).

Yang, H.-B. et al. Fermi surface evolution and Luttinger theorem in NaxCoO2: a systematic photoemission study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146401 (2005).

Ren, M.-Q. et al. Semiconductor-metal phase transition and emergent charge density waves in 1T-ZrX2 (X = Se, Te). Nano Lett. 22, 476–484 (2022).

Rossnagel, K. Suppression and emergence of charge-density waves at the surfaces of layered 1T-TiSe2 and 1T-TaS2 by in situ Rb deposition. N. J. Phys. 12, 125018 (2010).

Yang, Y. et al. High-resolution ARPES endstation for in situ electronic structure investigations at SSRF. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 31 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Krukau, A. V., Vydrov, O. A., Izmaylov, A. F. & Scuseria, G. E. Influence of the exchange screening parameter on the performance of screened hybrid functionals. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 224106 (2006).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Erratum: restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1–5 (2015).

Medeiros, P. V. C., Stafström, S. & Björk, J. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic perturbations on the electronic structure of graphene: Retaining an effective primitive cell band structure by band unfolding. Phys. Rev. B 89, 041407(R) (2014).

Medeiros, P. V. C., Tsirkin, S. S., Stafström, S. & Björk, J. Unfolding spinor wave functions and expectation values of general operators: Introducing the unfolding-density operator. Phys. Rev. B 91, 041116(R) (2015).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Kaneko, T., Ohta, Y. & Yunoki, S. Exciton-phonon cooperative mechanism of the triple-q charge-density-wave and antiferroelectric electron polarization in TiSe2. Phys. Rev. B 97, 155131 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. W.T. Zhang for the helpful discussions. The work at Shanghai Jiao Tong University is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China under Grant No. 2022YFA1402400 and No. 2021YFE0194100, the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality under Grant No. 21JC1403000. Y.H.C. acknowledges support from the Ministry of Science and Technology, the National Center for Theoretical Sciences (Grant No. 110-2124-M-002-012), and the National Center for High‑performance Computing in Taiwan. Part of this research is supported by the ME2 project under Contract No. 11227902 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China. J.J. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12174362). T.C.C. acknowledges the support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Science and Engineering, under Grant No. DE-FG02-07ER46383. P.C. acknowledges the sponsorship from Yangyang Development Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C. designed the project. Q.G. and P.C. with the aid of Z.H.T., J.X.P., S.T.C., Y.C.Y, Z.T.L., D.W.S., Z.S., and T.C.C. performed MBE growth, ARPES measurements, and data analysis. Y.H.C. performed calculations. Y.Z.W. and J. J. performed LEED measurements. P.C., Y.H.C., T.C.C., and Q.G. interpreted the results. P.C. wrote the paper with input from the coauthors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Q., Chan, Yh., Wang, Y. et al. Evidence of high-temperature exciton condensation in a two-dimensional semimetal. Nat Commun 14, 994 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36667-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36667-x

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.