Abstract

The dynamics of the first-order phase transitions involving a large displacement of atoms, for example, a liquid-solid transition, is generally dominated by the nucleation of the ordered phase and the growth of the nuclei, where the interfacial energy between the two phases plays an important role. On the other hand, electronic phase transitions seldom exhibit such a nucleation-growth behavior, probably because two-phase coexistence is not dominated by only the interfacial energy in such phase transitions. In the present paper, we report that the dynamics of a phase transition associated with an ordering of d orbitals in a vanadate exhibits a clear nucleation-growth behavior and that the interfacial energy between the orbital-ordered and -disordered phases dominated by the orbital-spin coupling can be experimentally obtained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Orbitals are one of the degrees of freedom in solids that interact with each other and order at low temperatures, similarly to the spin degrees of freedom. With the coupling of other degrees of freedom, orbitals often dominate various properties of materials. For example, a strong coupling between orbital and spin degrees of freedom leads to various intriguing phenomena in applied magnetic field, for example, the colossal magnetoresistance in various manganites1 and magnetic-field-induced phase transitions in various vanadates2,3. Although details of the ordered state in these compounds have been experimentally investigated quite thoroughly, the dynamics or the fluctuations of orbitals are less well understood, probably because there are not many experimental techniques to detect the dynamics of orbitals. Phase transitions dominated by orbital ordering are often of the first-order, but their dynamics has not been clarified so far.

One of the typical dynamics in the first-order phase transition is the nucleation and the growth of the nuclei. A characteristic time dependence of the transformed volume fraction resulting from such a nucleation-growth process has been observed in the crystallization of liquid metals (particularly metallic glasses)4,5,6,7,8,9, amorphous materials10,11,12, the crystallization of polymers13, and Martensitic transformations with a large displacement of atoms14,15. For such a nucleation-growth behavior to occur, the dominant energy must be the interfacial energy between the two phases, and this is typically the case for the phase transition with interfaces between solid and liquid, where almost negligible elastic energy appears as a bulk property of the domains.

The first-order electronic phase transitions with two-phase coexistence in crystals (Mott transition, magnetic transition, charge ordering, etc.) have been studied in various compounds, particularly focusing on the spatial distribution of the two phases16,17,18,19,20. The dynamics of the two-phase coexistence has also been studied in several compounds21,22,23,24,25, but they barely exhibit conventional nucleation-growth behavior. One of the possible reasons for the absence of nucleation-growth behavior is that the two-phase coexistence is dominated not only by the interfacial energy but more dominated by the bulk properties, particularly by the elastic energy of the domains, in such phase transitions.

Recently, the dynamics of the first-order phase transition has been studied for some organic conductors exhibiting charge ordering, and a nucleation-growth behavior has been suggested on the basis of the time dependence of several physical quantities from the supercooled state26,27,28,29. This motivated us to search for the orbital-ordered material whose phase transition is dominated by the nucleation growth behavior. Here, one way to avoid the disturbance in the nucleation-growth behavior is to use the materials exhibiting a phase transition without variants (twin structures) of the ordered phase that possibly hinder the growth of domains.

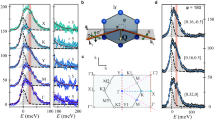

From this viewpoint, we chose BaV10O1530,31,32,33,34, which exhibits a sharp first-order phase transition at ~130 K caused by orbital ordering. In this compound, V ions form a bilayer quasi-triangular lattice and a structural phase transition characterized by V trimerization occurs below 130 K (Fig. 1), resulting in anomalies in various properties. This phase transition is caused by the ordering of the V t2g states; namely, at each side of the V trimer, the dxy, dyz, or dzx orbital of the neighboring V ions forms a bond in a spin-singlet state34. One of the characteristics in this phase transition is that in terms of the crystal structure, it is a phase transition from orthorhombic (Cmce) to orthorhombic (Pbca) and thus, no twin structure (variant) appears in the ordered phase. For more information on this compound, see Supplementary Note 1.

a, b Arrangement of the V ions a above and b below the transition temperature. In b, V trimers are highlighted in yellow. c (Left) Schematic of the orbital disordered (OD) phase (upper left) and the orbital-ordered (OO) cluster in the orbital disordered phase (lower left). (Right) Microscopic spin configurations and interactions in the OD phase (upper right) and at the boundary between the OO and the OD phases (lower right).

Results

Time dependence of resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and strain

The transition temperature of BaV10O15 itself is so high that rapid cooling in a conventional manner cannot yield a supercooled state. We found that crystals with reduced transition temperatures can be obtained by doping Ti into the V site in this compound. Figure 2a, c shows the temperature (T) dependences of the resistivity (ρ) and the magnetic susceptibility (χ) for BaV10t−xTixO15 (BVTO), respectively. As can be seen, the transition temperature to the orbital-ordered state decreases from 130 K for x = 0 to ~70 K for x = 0.15, and almost disappears for x = 0.20. Furthermore, we found that ρ(T) and χ(T) for x = 0.15 with a rapid cooling (200 K/min for ρ and 50 K/min for χ) and slow cooling (2 K/min for ρ and 5 K/min for χ) behave differently, as shown in Fig. 2b, d. For example, after rapid cooling of the sample, the resistivity is about two orders of magnitude smaller than that after slow cooling at the same T, indicating that the sample is still in the high-T (HT) phase (a supercooled state), but with increasing T at the rate of 2 K/min, resistivity increases at ~70 K and merges with that for the slowly cooled sample, indicating a phase transition to the low-T (LT) phase. With further increasing T, ρ decreases at ~90 K, indicating a phase transition to the HT phase. Such a reentrant behavior is commonly observed when the temperature is increased from a supercooled state28,35. Note that the reentrant behavior is not observed but χ(T) behaves similarly both after slow cooling and rapid cooling for x = 0.10, as shown in Fig. 2d. For more detailed cooling-rate dependence, see Supplementary Note 2.

a T dependence of resistivity (ρ) for various values of x. b T dependence of resistivity along the c axis (ρc) for BVTO with x = 0.15 in a warming run (2 K/min) after rapid cooling (200 K/min, red) and in a cooling run and a warming run with a slow temperature change (2 K/min, blue). c T dependence of magnetic susceptibility along the a-axis (χa) for BVTO. d T dependence of χa for BVTO with x = 0.10 and x = 0.15 with rapid cooling (50 K/min, red) and slow cooling (5 K/min, blue) measured both in a cooling run and a warming run (5 K/min).

To study the dynamics of the phase transition, we measured the time (t) dependences of ρ (along the b-axis), χ (along the a-axis), and strain ΔL/L (along the b-axis) after rapid cooling (30 K/min for ρ and ΔL/L and 50 K/min for χ) from T > 100 K to various temperatures for BVTO with x = 0.15, which exhibits a supercooled state and a reentrant behavior for their T dependences. As shown in Fig. 3a–c, all three quantities exhibit a clear t dependence; ρ, for example, hardly changes but remains at ρHT corresponding to the value in the HT phase, for a while after rapid cooling, but starts increasing at a certain time and is saturated at ρLT, corresponding to the value in the LT phase. As a rough estimate of the transformation time from the HT to the LT phase, τ1/2 at which logρ–logρHT becomes a half of logρLT–logρHT is plotted as a function of T in Fig. 3d by red circles. As can be seen, τ1/2 obtained from ρ decreases with increasing T up to ~70 K, but it takes a minimum and then increases with further increasing T. Note that the t dependences of χ and ΔL/L produce similar time–temperature–transformation (TTT) curves of τ1/2 represented by black crosses for χ and blue open squares for ΔL/L in Fig. 3d, which was estimated as the time at which χ or |ΔL/L| increases by half the increase from the HT to the LT phase. Such TTT curves have been observed in various systems exhibiting a first-order phase transition8,9,10,11,13,27,28, but have not been observed for the electronic phase transition in inorganic materials. Note that the value of the minimum τ1/2 at ~70 K (~100 s) is sufficiently long so that the low-T phase does not appear during the rapid cooling with a rate of several tens K/min for x = 0.15. For x = 0.10 or less, it is probably much shorter and thus, the supercooled state does not appear even with the rapid cooling. As another example of the materials exhibiting a similar TTT curve, the t dependence of ΔL/L for the Sr-doped sample, Ba1−xSrxV10O15 with x = 0.06, is shown in the Supplementary Note 3.

a–c Time dependence of a resistivity along the b axis (ρb), b magnetic susceptibility along the a axis (χa), and c strain along the b axis (|ΔLb/Lb|) after rapid cooling (30 K/min for ρ and ΔL/L and 50 K/min for χ) to each temperature. The data in c are offset for clarity. d τ1/2 estimated from ρb (red circles), |ΔLb/Lb| (blue open squares), and χa (black crosses). For the estimate of τ1/2 for each quantity, see the text.

Analysis of the time dependence by the Kolmogorov-Johnson-Mehl-Avrami model

The time dependence of the transformed volume in the nucleation-growth process has been discussed using the Kolmogorov–Johnson–Mehl–Avrami (KJMA) model36,37,38,39, which takes account of nucleation, the growth of the nuclei, and the impingement of the grown nuclei (see Supplementary Discussion 1). In this model, the time dependence of the transformed volume fraction V(t) is given by

where τ is the transformation time and n is the Avrami exponent, which is four in the case of isotropic three-dimensional growth but can be smaller if nucleus growth is anisotropic. τ0 (the transient time) comes from the time dependence of the nucleation rate N(t). Namely, there is no nucleus of the low-T phase immediately after rapid cooling to a certain temperature (i.e., N(t = 0) = 0), and it takes some time until the distribution of the size of various clusters attains a steady state and the time dependence of the nucleation rate N(t) becomes constant value of N0. The functional form of N(t) has been calculated theoretically40, but for the analysis of the experimental data, we assume that N(t) = 0 for t < τ0 and N(t) = N0 for t ≥ τ0.

If we assume τ0 = 0 in Eq. (1), the exponent n and the transformation time τ can be obtained by plotting ln(−ln(1−V(t))) as a function of ln t39. Among the three quantities measured above, strain ΔL/L directly corresponds to the volume fraction of transformation, V(t). Namely, the direction of the a-, b-, and c-axes in the orthorhombic structure does not change with the phase transition in the present compound and as a result, ΔL/L along any directions is proportional to V(t) (see Supplementary Note 4). Thus, we plot ln(−ln(1−x(t))) with x(t) = |ΔL(t)/ΔL(∞)| as a function of ln t as shown in Fig. 4a, b. As can be seen, a clear kink structure, a subsequent linear increase, and another kink with saturation are observed in this plot above 76 K [Fig. 4a]. However, the slope, which corresponds to the exponent n, is larger than four above 78 K, which is an unphysical value. This result suggests that the transient time τ0 is nonzero above 78 K. We have fitted the data x(t) = |ΔL(t)/ΔL(∞)| with Eq. (1) with a finite τ0 (see Supplementary Note 5), and found that τ0 obtained by the fitting is positive for T ≥ 78 K, but for T ≤ 77 K, it is negligible or negative and is thus assumed to be 0 in the following. We plot ln(−ln(1 − x(t))) as a function of ln(t − τ0) in Fig. 4c. As can be seen, all the data above 70 K exhibit a linear increase with a similar slope, n = 3–4.

a, b ln(−ln(1 − x(t))) vs. ln t, where x(t) = |ΔL(t)/ΔL(∞)| (ΔL is the strain along the b axis) a above 73 K and b below 69 K. The dashed line in b is the curve fitted by the sum of Eq. (1) and Eq. (2). c ln(−ln(1 − x(t))) vs. ln(t − τ0), where τ0 is obtained by fitting with Eq. (1). d Transformation time τ, e Avrami exponent n, and f diffusion component βτ1/2 and the transient time τ0 as a function of T obtained by the fitting with the sum of Eq. (1) and Eq. (2). The solid line in d is the fitting with Eq. (3).

On the hand, at lower temperatures (T ≤ 69 K shown in Fig. 4b), the clear kink before the linear increase with t is smeared out but a gradual increase appears for small t in ln(−ln(1 − x(t))), which is followed by an increase with a larger slope. It was found that the slope for the initial increase in the plot of ln(x(t)) vs. ln t is close to 1/2 (see Supplementary Note 6), suggesting that the initial increase is dominated by one-dimensional diffusive motion of the interface22. Here, we assume that a transformation of a part of the region in the crystal is dominated by diffusive motion, and thus, V(t) is given by the sum of the nucleation-growth formula given by Eq. (1) and that of the diffusive motion given by

and fits the data obtained at T ≤ 77 K. An example of the fitting result is shown by the dashed line in Fig. 4b for the data obtained at 55 K. This one-dimensional diffusive motion is probably caused by the anisotropic growth of domains dominated by the bulk elastic energy.

The transformation time τ, the Avrami exponent n, the transient time τ0, and βτ1/2 (corresponding to the ratio of the region dominated by Vdiff to that dominated by the nucleation-growth behavior at t = τ) obtained by the fitting above are shown in Fig. 4d–f. As can be seen, τ exhibits a minimum at ~70 K, n is 3–4, τ0 decreases with decreasing T, and βτ1/2 increases with decreasing T but is less than 0.15. These experimental results indicate that the dynamics of the phase transition is mainly dominated by the three-dimensional nucleation and growth with a finite transient time near the transition temperature. For additional data for the time dependence of various quantities, see Supplementary Note 7.

Temperature dependence of the dynamics and interfacial energy

Let us now discuss the T dependence of the phenomena. According to the nucleation-growth theory (see Supplementary Discussion 2), the transformation time τ at each T is proportional to \(\left( {{\it{N}}_0{\it{v}}_0^3} \right)^{ - 1/4}\), where ν0 is the constant speed for the interface and N0 is the constant nucleation rate for t > τ0. The T dependence of τ dominated by N0 and ν0 is given by9,10

Here, T1 corresponds to the height of the energy barrier for adding one atom to the ordered phase, T2 corresponds to the height of the energy barrier to overcome when the size of a cluster for the ordered phase exceeds a critical value, which is dominated by the interfacial energy between the two phases, and τph is the inverse frequency of the characteristic phonon for the phase transition.

We fitted the T dependence of the transformation time τ obtained experimentally from the time-dependent strain (shown by the solid circles in Fig. 4d) with Eq. (3) (shown by the solid line in the same figure), and obtained the following parameters; T1 = 2133 K, T2 = 87.6 K, Tc = 103 K, and τph = 1.0 × 10−15 s (see also Supplementary Note 8).

T2 approximately corresponds to the interfacial energy per atom. Note that the interfacial energy between the A and B phases means that the energy is higher when the A and B components are next to each other than that when A and A or B and B are next to each other. For example, the interfacial energy between the two ordered states with different directions of the order parameter (in ferroelectrics or ferromagnets) is given by \(\frac{{\it{K}}}{2}\left( {\nabla {\boldsymbol{m}}} \right)^2\), where m is the order parameter, by the Ginzburg–Landau theory, and ∇m has a finite value only at the interface. On the other hand, the interfacial energy between the ordered state and the disordered state in this picture is small since, in conventional phase transitions, it is unlikely that the energy cost between a component in the ordered state and that in the disordered state is larger than that between two components both in either the ordered or the disordered state. On the basis of the Ginzburg–Landau theory, such an interfacial energy corresponds to a four-body correlation function, which is smaller than two-body correlation functions, for example, in conventional systems with a single order parameter. Indeed, many of the nucleation-growth behaviors in the first-order phase transition are observed only in systems in which the phase transition is accompanied by a large displacement of atoms.

However, the situation is critically different in the present compound, where there are spin and orbital degrees of freedom that are strongly coupled with each other, leading to the Kugel–Khomskii interaction with a four-body term, (si·sj)(τi·τj) (si and τi represent the spin and orbital degrees of freedom, respectively)41. In such a case, a change in the orbital state with orbital ordering can cause a change in the magnetic interaction, and accordingly, an energy cost can arise at the boundary between the orbital-ordered and -disordered states. In the case of the present compound, there is an S = 1 spin at each V site in the orbital-disordered phase, and these spins are antiferromagnetically (AF) coupled with each other (Fig. 1c, upper panels). In the orbital-ordered phase, on the other hand, the V spins forming trimers are in a spin-singlet state. Thus, if the orbital-ordered and -disordered phases are next to each other, the V spins in the orbital-disordered phase on the boundary cost energy since there are fewer spins to be AF coupled in the orbital-ordered phase. This leads to an interfacial energy dominated by the AF interaction (Fig. 1c, lower panels). Note that the change in the magnetic interaction with orbital ordering (larger AF coupling within the V trimer and smaller coupling between the trimers) is essential to this interfacial energy. This picture is also consistent with the isotropic growth of nuclei experimentally observed, since, on the basis of the crystal structure, the magnetic interaction and the number of neighboring sites are fairly isotropic in the present compound.

We point out that the interfacial energy between the ordered and the disordered phases can affect the phase transition and thus will be important in general even if it does not exhibit the dynamics of the nucleation-growth behavior. One of the accomplishments in the present study is a quantitative estimate of such an interfacial energy from the experiment, T2 = 87.6 K. The AF interaction J of the present compound estimated from the Weiss temperature of the magnetic susceptibility (θ = s(s + 1)zJ/3 = 1.2 × 103 K33 with the number of nearest neighbor sites z ~6), is ~300 K, which is comparable to T2 = 87.6 K, considering various factors omitted in the estimation of the interfacial energy.

Such orbital–spin coupling is an innovative mechanism of the interfacial energy, yielding a liquid-like domains with the electronic phase transition. Since such domains can be relatively easily controlled by temperatures and various external fields, they not only are the good systems to study the dynamics of the phase transition, but also can be a platform for intriguing physical properties arising from domains and interfaces.

Methods

Sample preparation

The single crystals of BaV10−xTixO15 were grown by the floating-zone technique. BaCO3, V2O3, and Ti were mixed and pressed into a rod and was sintered at 1300 °C for 12 h in a flow of H2 = 7%/Ar gas. Then, the rod was melted by the floating-zone furnace with four halogen lamps in a flow of H2 = 7%/Ar gas with a feed speed of 8 mm/h. The orientation of the grown single crystals was determined by the Laue method and the crystals were cut in a rectangular shape.

Measurement of resistivity, magnetization, and strain

Resistivity of the sample was measured by a four-probe technique with silver paste as electrodes. Magnetization was measured by a SQUID magnetometer. Strain was measured by a strain-gauge technique. For rapid cooling in the resistivity and strain measurement, a heater (a strain gauge with a resistance of ~120 Ω) was attached to the sample, and the temperature of the cryostat is kept at a specific temperature and then, an appropriate magnitude of electric power was applied to the heater so that the temperature of the sample locally increases above 100 K. Then, we turned off the electric power to the heater and waited until the value of the resistivity or the strain becomes stable. After that, we started measuring the time dependence. For rapid cooling in the magnetization measurement, we used the temperature controller originally attached to the magnetometer, by which the rate in the temperature sweep can be increased to 50 K/min. More detailed description about the measurement is seen in the Supplementary Methods 1.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Millis, A. J. Lattice effects in magnetoresistive manganese perovskites. Nature 392, 147 (1998).

Ren, Y. et al. Temperature-induced magnetization reversal in a YVO3 single crystal. Nature 396, 441 (1998).

Suzuki, T., Katsumura, M., Taniguchi, K., Arima, T. & Katsufuji, T. Orbital ordering and magnetic field effect in MnV2O4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 127203 (2007).

Coleman, E. Crystallization of Fe, Co and Ni based metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. 23, 161 (1976).

Scott, M. G. The crystallization kinetics of Fe-Ni based metallic glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 13, 291 (1978).

Ranganathan, S. & Heimendahl, M. V. The three activation energies with isothermal transformations: applications to metallic glasses. J. Mater. Sci. 16, 2401 (1981).

Herlach, D. M. Non-equilibrium solidification of undercooled metallic melts. Mater. Sci. Eng. R12, 177 (1994).

Kim, Y. J., Busch, R., Johnson, W. L., Rulison, A. J. & Rhim, W. K. Experimental determination of a time-temperature transformation diagram of the undercooled Zr41.2Ti13.8Cu12.5Ni10.0Be22.5 alloy using the containerless electrostatic levitation processing technique. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68, 1057 (1996).

Löffler, J. F., Schroers, J. & Johnson, W. L. Time-temperature-transformation diagram and microstructures of bulk glass forming Pd40Cu30Ni10P20. Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 681 (2000).

Uhlmann, D. R. Glass formation. J. Noncryst. Solids 25, 42 (1977).

Orava, J., Greer, A. L., Gholipour, B., Hewak, D. W. & Smith, C. E. Characterization of supercooled liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 and its crystallization by ultrafast-heating calorimetry. Nat. Mater. 11, 279 (2012).

Sutou, Y., Kamada, T., Sumiya, M., Saito, Y. & Koike, J. Crystallization process and thermal stability of Ge1Cu2Te3 amorphous thin films for use as phase change materials. Acta Mater. 60, 872 (2012).

Saeidlou, S., Huneault, M. A., Li, H. & Park, C. B. Poly(lactic acid) crystallization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 37, 1657 (2012).

Yamada, Y., Hamaya, N., Axe, J. D. & Shapiro, S. M. Nucleation, growth, and scaling in a pressure-induced first-order phase transformation: RbI. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 1665 (1984).

Abe, H. et al. Kinetics of the martensitic transition in In-Tl alloys. Phys. Rev. B 50, 9020 (1994).

Uehara, M., Mori, S., Chen, C. H. & Cheong, S.-W. Percolative phase separation underlies colossal magnetoresistance in mixed-valent manganites. Nature 399, 560 (1999).

Podzorov, V., Kim, B. G., Kiryukhin, V., Gershenson, M. E. & Cheong, S.-W. Martensitic accommodation strain and the metal-insulator transition in manganites. Phys. Rev. B 64, 140406 (2001).

Qazilbash, M. M. et al. Mott transition in VO2 revealed by infrared spectroscopy and nano-imaging. Science 318, 1750 (2007).

Laverock, J. et al. Direct observation of decoupled structural and electronic transitions and an ambient pressure monocliniclike metallic phase of VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 216402 (2014).

McLeod, A. S. et al. Nanotextured phase coexistence in the correlated insulator V2O3. Nat. Phys. 13, 80 (2017).

Anane, A. et al. Colossal resistive relaxation effects in a Pr0.67Ca0.33MnO3 single crystal. Phys. Rev. B 59, 77 (1999).

Uehara, M. & Cheong, S. W. Relaxation between charge order and ferromagnetism in manganites: indication of structural phase separation. Europhys. Lett. 52, 674 (2000).

Levy, P., Parisi, F., Granja, L., Indelicato, E. & Polla, G. Novel dynamical effects and persistent memory in phase separated manganites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 137001 (2002).

Ramírez, J.-G., Sharoni, A., Dubi, Y., Gómez, M. E. & Schuller, I. K. First-order reversal curve measurements of the metal-insulator transition in VO2: signatures of persistent metallic domains. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235110 (2009).

Ward, T. Z., Gai, Z., Guo, H. W., Yin, L. F. & Shen, J. Dynamics of a first-order electronic phase transition in manganites. Phys. Rev. B 83, 125125 (2011).

Kagawa, F. et al. Charge-cluster glass in an organic conductor. Nat. Phys. 9, 419 (2013).

Sato, T., Miyagawa, K. & Kanoda, K. Electronic crystal growth. Science 357, 1378 (2017).

Sasaki, S. et al. Crystallization and vitrification of electrons in a glass-forming charge liquid. Science 357, 1381 (2017).

Sato, T. et al. Strange metal from a frustration-driven charge order instability. Nat. Mater. 18, 229 (2019).

Liu, G. & Greedan, J. E. Structure and magnetism in AB 10O15+x (A= Sr, Ba; B= V, Cr; x= 0-1): evidence for geometric frustration. J. Solid State Chem. 122, 416 (1996).

Bridges, C. A., Greedan, J. E. & Kleinke, H. Insights on the origin of the structural phase transition in BaV10O15 from electronic structure calculations and the effect of Ti-doping on its structure and electrical transport properties. J. Solid State Chem. 177, 4516 (2004).

Bridges, C. A. & Greedan, J. E. Phase transitions and electrical transport in the mixed-valence V2+/V3+ oxide BaV10O15. J. Solid State Chem. 177, 1098 (2004).

Kajita, T. et al. Opening of a charge gap with V trimerization in BaV10O15. Phys. Rev. B 81, 060405(R) (2010).

Takubo, K. et al. Orbital states of v trimers in BaV10O15 detected by resonant x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 86, 085141 (2012).

Yoshida, M. et al. Controlling charge-density-wave states in nano-thick crystals of 1T-TaS2. Sci. Rep. 4, 7302 (2014).

Kolmogorov, A. N. Statistical theory of nucleation processes. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Math. Ser. 3, 355 (1937).

Johnson, W. A. & Mehl, P. A. Reaction kinetics in processes of nucleation and growth. Trans. Am. Inst. Miner. Metall. Eng. 135, 416 (1939).

Avrami, M. Kinetics of phase change. I general theory. J. Chem. Phys. 7, 1103 (1939).

Christian, J. The Theory of Transformations in Metals and Alloys (Pergamon, 2002).

Kelton, K. F., Greer, A. L. & Thompson, C. V. Transient nucleation in condensed systems. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 6261 (1983).

Kugel, K. I. & Khomskii, D. I. Crystal-structure and magnetic properties of substances with orbital degeneracy. Z. Exsp. Thor. Fiz. 64, 369 (1973). [Sov. Phys. JETP 37, 725 (1973)].

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Mochizuki and Y. Tabe for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant no. 19H01853 and JST CREST Grant no. JPMJCR15Q2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T. Katsufuji and T. Katjita planned the project. T. Kajita and S.Y. grew the single crystals. T. Kajita, S.Y., Y.K., and K.U. performed the measurement of resistivity and strain. T. Kajita and S.Y. performed the measurement of magnetization. T. Katsufji wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Katsufuji, T., Kajita, T., Yano, S. et al. Nucleation and growth of orbital ordering. Nat Commun 11, 2324 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16004-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16004-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.