Abstract

Stochastic pulsing of gene expression can generate phenotypic diversity in a genetically identical population of cells, but it is unclear whether it has a role in the development of multicellular systems. Here, we show how stochastic pulsing of gene expression enables spatial patterns to form in a model multicellular system, Bacillus subtilis bacterial biofilms. We use quantitative microscopy and time-lapse imaging to observe pulses in the activity of the general stress response sigma factor σB in individual cells during biofilm development. Both σB and sporulation activity increase in a gradient, peaking at the top of the biofilm, even though σB represses sporulation. As predicted by a simple mathematical model, increasing σB expression shifts the peak of sporulation to the middle of the biofilm. Our results demonstrate how stochastic pulsing of gene expression can play a key role in pattern formation during biofilm development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spatial patterns of gene expression play a key role in development1,2. Although many patterns are formed in response to spatial gradients of initiating signals3,4, noise in the form of transient fluctuations in gene expression can also initiate patterns by generating differences in gene expression within a population of identical cells5,6,7,8,9. Noise in gene expression has been observed in major regulators at the level of individual bacterial cells10,11,12. This noise is hypothesised to play a functional role, generating phenotypic diversity that can allow the population to bet-hedge against variable environments13 by promoting a subset of cells to enter a slow growing persistent state that can survive antibiotic treatment14,15.

Recent work in multiple systems has revealed that phenotypic diversity in a population of genetically identical cells can be achieved through the pulsed activity of transcriptional regulators. Stochastic pulsing of key regulators has been observed in multiple systems, from microbes to mammalian cell culture16. However, the role of stochastic pulses of gene expression in the development of multicellular systems remains poorly understood. Here we use Bacillus subtilis bacterial biofilms as a model multicellular system to investigate the role of stochastic pulses of gene expression during pattern formation.

Bacterial biofilms17,18,19 are complex multicellular systems that exhibit a variety of spatial structures including vasculature20, protective layers21,22, and functional specialisation23. Snapshots of B. subtilis biofilms containing fluorescent reporters for key pathways have revealed the formation of spatial patterns within the biofilm, with heterogeneous cell states for motility, sporulation, surfactin production, and matrix formation24. These cell states25 are often heterogeneously distributed in a “salt and pepper” fashion26, yet are spatially localised to specific regions of the biofilm24, suggesting a role for both spatial signalling and noise in gene expression during pattern formation in biofilms. Under planktonic growth conditions, several pathways have been shown to display high noise in gene expression in B. subtilis. These include competence27, matrix production28, sporulation29 and, in some conditions, the general stress response30. However, it remains unclear how stochastic pulses in gene expression at the single cell level plays a role in the formation of spatial patterns in biofilms.

In this study, we use the B. subtilis general stress response pathway, mediated by the alternative sigma factor σB, as a model system to examine dynamic and heterogeneous gene expression in biofilms. σB modulates more than 150 target genes in response to diverse stresses31,32. It is an ideal system for examining gene regulation dynamics in biofilms, as it is well characterised (see Fig. 1a for details of its regulation) and its gene regulatory dynamics have already been elucidated at the single cell level in microcolonies30,33. As a response to various stresses, entering the σB active state can be considered an alternative protective strategy to that of forming a dormant spore (discussed in ref. 32). Indeed, σB activation has been shown to repress sporulation in planktonic growth34,35,36.

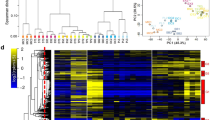

a Network diagram of σB circuit. Energy stress causes the complex RsbQP (QP, purple) to dephosphorylate RsbV (V, blue). Environmental stress releases RsbT (T, purple) from the stressosome (consisting of RsbR (R, orange) and RsbS (S, orange) subunits). RsbT then binds RsbU (U, purple) and activates it, with active RsbU dephosphorylating RsbV. Dephosphorylated RsbV (V, blue) binds to RsbW (W, red), releasing σB (σB, green) to bind to RNA polymerase and activate its target genes, including its own operon. b Filmstrip of σB activation in a WT B. subtilis microcolony grown in biofilm promoting medium. Heterogeneous expression levels of PsigB-YFP (green) reflect pulsing activity. Numbers indicate time in hours and minutes. c Single cell fluorescence values for constitutive fluorescent reporter (PsigA-RFP) over time (representative traces). d–f Single cell fluorescence values for PsigB-YFP reporter over time for WT d, ΔrsbRU e, and ΔrsbQP f, strains. The time in hours is relative to the start of analysis. g, h Histograms of fluorescence intensities of WT cells for the constitutive reporter PsigA-RFP g and PsigB-YFP reporter h (For both, cells: 1157, movies: 6, experiments 2). i, j Histograms of PsigB-YFP expression for ΔrsbRU strain i (cells: 1178, movies: 5, experiments: 3) and ΔrsbQP strain j (cells: 1290, movies: 8, experiments 3). Histograms in g–j include all frames in movies with more than 8 cells. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

σB can be activated by two broad classes of stress: energy and environmental stress32,37 (Fig. 1a). Energy stresses include ATP limitation through the addition of inhibitors (e.g. CCCP, MPA), entry into stationary phase, or carbon-limiting media. Environmental stresses shown to activate σB include ethanol, NaCl, and heat. These responses have been characterised in planktonic growth, and it is unclear what the activation dynamics are of σB during biofilm formation. Biofilms can contain spatially localised stress patterns38, as well as gradients of nutrients away from the nutrient source39, and thus to understand σB activation during biofilm formation it is critical to examine gene expression in individual cells.

The energy stress pathway is mediated by a protein complex of the alpha/beta hydrolase RsbQ and serine phosphatase RsbP40,41. The environmental stress pathway is mediated through a sensing module termed the stressosome42, which controls the activity of the phosphatase RsbU. Under unstressed conditions, σB is inactive due to being bound to its anti-sigma factor RsbW. Under stress conditions, either RsbP or RsbU activates σB by de-phosphorylating its anti-anti-sigma factor RsbV, allowing RsbV to bind the anti-sigma factor RsbW and release σB43 (Fig. 1a). Although the regulation of the energy stress and environmental stress pathways are similar, strikingly different activation dynamics are observed in individual cells. Under energy stress conditions, σB is activated in a series of stochastic pulses in microcolonies grown on agarose pads30 due to continuous activation through the phosphatase RsbP. Environmental stresses however generate a single adaptive pulse in σB activity33 due to regulation of RsbU via the stressosome. A key aspect of the generation of these pulses is that σB activates its own operon, consisting of σB, RsbV and RsbW. This results in both a positive feedback loop through the activation of σB, which amplifies fluctuations, and a negative feedback loop through the activation of RsbW, which terminates the pulse. Similar pulsing dynamics under energy stress have recently been observed in other alternative sigma factors that share a similar regulatory structure44.

In this work, we examine σB expression in an isolate of B. subtilis capable of forming biofilms. Under biofilm growth conditions we find that σB is activated in a series of stochastic pulses, both in microcolonies and in developing biofilms. Moreover, we observe a gradient of σB activation in B. subtilis biofilms, with the highest level of expression at the top of the biofilm. This gradient depends on the energy stress pathway. However, most spores are also found at the top of the biofilm24, even though σB has been shown to repress sporulation34,35,36. Through modelling and experiment, we propose that stochastic pulsing of σB allows cells to activate either σB or sporulation, allowing mutually exclusive cell states to co-exist in the same regions of the biofilm. Thus, stochastic pulses of gene expression can enable the formation of simple spatial patterns in biofilms.

Results

σ B pulses in microcolonies grown under biofilm conditions

To investigate σB activity in B. subtilis biofilms we constructed a σB (PsigB-YFP) reporter strain in a B. subtilis background capable of biofilm formation (NCIB 3610). The PsigB-YFP construct contains the upstream region of RsbV from the σB operon, which contains a σB-binding site. We used expression of this reporter as a proxy for σB activity, as carried out previously30. This reporter strain also contained a constitutive σA reporter for comparison (PsigA-RFP), which contains the σA-binding site from the trpE gene (see Supplementary Methods for further details). Previous work using laboratory B. subtilis strains (Py79 and 168 Marburg backgrounds) incapable of forming biofilms demonstrated that σB pulses stochastically under energy stress in individual cells growing in microcolonies30. However, recent work shows that media and growing conditions affect σB dynamics45. We first checked whether pulsatile dynamics are observed using our reporter strain in microcolonies grown on agar pads of biofilm-promoting medium (MSgg, see the “Methods” section). The biofilm media was diluted 1:100 to promote microcolony formation, as carried out previously24. Under these conditions, pulses of gene expression were observed in the PsigB-YFP reporter (Fig. 1b, d), but not in the constitutive reporter (Fig. 1c), similar to dynamics previously observed after application of energy stress30.

The observed pulsed σB gene expression is not dependent on the environmental stress pathway, as pulsing gene expression is still observed after knocking out the operon containing the main environmental stress pathway components RsbR, RsbS, RsbT, and RbsU (ΔrsbRU) (Fig. 1e). The energy stress pathway, however, is required for the pulsing dynamics, as PsigB-YFP levels drop to background levels in a reporter strain where RsbQ and RsbP are knocked out (ΔrsbQP) (Fig. 1f, j). The pulsed gene expression results in a long tailed distribution of fluorescent reporter intensities in snapshots of gene expression from individual cells in the WT (mean 49.06 ± 16.14, coefficient of variation (CV) 0.42, Fig. 1h) and ΔrsbRU backgrounds (mean 72.70 ± 19.07, CV 0.27, Fig. 1i). The long tailed distribution is caused by σB infrequently pulsing on to a high level. This results in most cells having low PsigB-YFP expression levels, with only a few cells having high expression levels at a given time. This causes the σB pathway to have a higher level of noise in gene expression than the constitutive PsigA-RFP reporter, which has a lower CV (CV 0.13, Fig. 1g).

σ B forms an activation gradient in biofilms

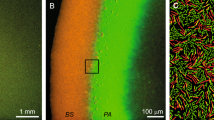

We next examined σB expression in developing biofilms grown on a solid agar surface (see the “Methods” section). To quantify σB regulation in the biofilm, we carried out confocal microscopy on thin slices of samples from the centre of biofilms at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after inoculation. (In this paper our samples are from the centre of the biofilm colony, which has a wrinkle morphology distinct from the smoother edge of the biofilm (Supplementary Fig. 1).) The microscopy settings were configured to minimise possible bleed-through of signal between the acquisition channels (see the “Methods” section). We observed a distinct pattern of σB activation, with a gradient of σB expression that peaks at the top of the biofilm (Fig. 2a, d). The gradient can be observed at multiple timepoints during biofilm development (see Supplementary Fig. 2A). This gradient in expression was not due to variation in maturation properties of the yellow fluorescent protein through the biofilm, as the expression of a reporter using the same fluorescent protein for a different alternative sigma factor, σW (PydbS-YFP) that is active during biofilm formation46,47,48 (see Supplementary Fig. 3), and PsigA-YFP (see Supplementary Fig. 4) were uniform throughout the biofilm and did not display a gradient of expression.

a–c Confocal microscopy images of slices of central parts of 48 h biofilm colony with merged channels for constitutive fluorescent reporter, PsigA-RFP, in red and PsigB-YFP in green. a WT cells, b ΔrsbRU cells, c ΔrsbQP cells. Scale bar 100 μm. d The ratio of PsigB-YFP to PsigA-RFP expression levels in the three strains as measured from the top of the colony, error bars indicate the SEM (WT: n = 13 images from three experiments, ΔrsbRU: n = 10 from two experiments, ΔrsbQP: n = 11 from two experiments). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Recent work has found that B. subtilis often forms an association with plant roots in the soil to form a possible symbiotic relationship with the plant49. In order to test whether a gradient in σB expression is a general phenomenon during biofilm development, we examined our B. subtilis PsigB-YFP reporter cells growing on Arabidopsis thaliana roots. We observed a gradient in PsigB-YFP expression in WT cells that was not present in a ΔσB background (see Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting that a σB gradient can be present in a range of growth conditions.

We next examined which of the σB major input pathways (energy or environmental stress) are required for the generation of the σB expression gradient in biofilms. First, to test the role of the environmental stress pathway we examined σB expression in the ΔrsbRU reporter strain using our standard biofilm colony growing condition on MSgg agar. The overall pattern of σB activation in the ΔrsbRU background resembled WT (Fig. 2b, d, Supplementary Fig. 2B). In contrast, deletion of the energy stress pathway (ΔrsbQP) significantly reduced σB expression in biofilms and resulted in an attenuated gradient (Fig. 2c, d, Supplementary Fig. 2C).

To test whether σB might pulse in biofilms, we examined whether a long-tailed distribution of PsigB-YFP fluorescence intensities was present in snapshot images of biofilms, similar to the long tails observed in small colonies that exhibited pulsing (Fig. 1h, i). Segmentation of individual cells in biofilm slices from high magnification images revealed variation in intensity of PsigB-YFP expression in adjacent cells. At the top edge of the biofilm we observed a long tail in the histogram of cell expression, again dependent on the energy stress pathway (Fig. 3). When we sampled histograms throughout the remainder of the biofilm we observed that the distribution became narrower and less long tailed as we moved away from the top of the biofilm (Supplementary Fig. 6), due to the diminished activity of σB.

a–c High magnification confocal images of the top 25 μm of the central part of a B. subtilis biofilm. Merged PsigA-RFP (red) and PsigB-YFP (green) channels for a WT, b ΔrsbRU, and c ΔrsbQP, respectively. Yellow lines indicate the top edge of the biofilm and the white lines mark the 5 and 7 μm isolines. Scale bar is 5 μm. d Histograms of normalised cell fluorescence in a range from 5 to 7 μm from the top of the biofilm. The YFP values are normalised by the mean RFP fluorescence in the range for that image. The error represents the standard deviation of the histogram for each image (WT histograms from 4231 cells, n = 24 images from five experiments, ΔrsbRU histograms from 3268 cells, n = 18 from three experiments, ΔrsbQP histograms from 2481 cells, n = 16 from three experiments). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

σ B pulses occur throughout biofilm formation

We hypothesised that the observed gradient in σB levels (Fig. 2) was generated by σB pulsing in a growing biofilm. To confirm this we developed a time-lapse protocol that allowed us to examine single cell σB activation dynamics across a part of a growing biofilm colony (see the “Methods” section). By growing the biofilm against the glass bottom of a dish (Fig 4a), we were able to image, with single cell resolution, the growth of a biofilm that exhibited characteristic biofilm properties such as wrinkle formation (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Movie 1). We imaged the ΔrsbRU background to avoid σB activation due to repeated laser illumination through the environmental stress pathway, as the pathway can be activated through the blue light sensor, ytvA50.

We were able to observe the establishment of the PsigB-YFP gradient (Fig. 4b, c) that was present in snapshots from cryoslices of the biofilm (Supplementary Fig. 2). The PsigB-YFP gradient developed through time, peaking at 72 h after inoculation. We then examined σB dynamics in individual cells at a high frequency, by taking time-lapse images every 10 min for up to 96 h. By extracting single cell time-traces during the development of the biofilm, we found sustained pulsing of σB in individual cells (Fig. 4d) at the top of the biofilm throughout biofilm development (Supplementary Movie 2). These pulses lead to a long-tailed histogram of single cell PsigB-YFP levels (Supplementary Fig. 7D), similar to that observed in snapshots of biofilm slices (Fig. 3), which was absent from the PsigA-RFP control (Supplementary Fig. 7B). We also observed heterogeneous expression, as well as a gradient of gene expression across the biofilm, for reporters of two genes regulated by σB, csbB51, and yflA52 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, σB pulses through the energy stress pathway during biofilm development, resulting in a heterogeneous distribution of σB active and inactive states, which are reflected in the expression levels of σB targets.

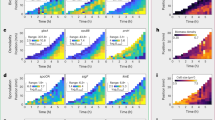

a Experimental setup used to capture time-lapse confocal images of the growing biofilm. A glass bottom dish is partially filled with MSgg agar. Cells are inoculated on the agar surface in contact with the glass. The biofilm grows on the agar surface, allowing time-lapse microscopy across a cross-section of the biofilm. b Quantification of σB gradient from live biofilm snapshots taken every 12 h, error bars indicate the SEM. n = 17 from two experiments. c Snapshots of the top of the live biofilms taken at 12 h intervals after inoculation shows development of a σB gradient of expression. Snapshots are merged PsigA-RFP (red) and PsigB-YFP (green) channels. Scale bar is 20 μm. d Ratiometric expression of PsigB-YFP/PsigA–RFP in a selection of cells tracked for over 40 h shows sustained pulsing of PsigB-YFP during biofilm growth. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Pulsing allows mutually exclusive states to co-exist

As well as the gradient of σB expression, we also observed a gradient of spore formation (using a reporter for late stage sporulation (PsspB-YFP),53) in the biofilm, with the highest number of cells transitioning to spores at the top of the biofilm (blue line, Fig. 5a). However, σB has been proposed to repress sporulation in planktonic growth34,35,36. The repression occurs due to σB activating expression of the phosphatase Spo0E, a negative regulator of the master regulator of sporulation, Spo0A34,35. We first confirmed that sporulation is not required for the gradient in σB expression (Supplementary Fig. 8D) by deleting σF, which is required for spore formation. Next, to test whether σB represses sporulation during biofilm formation we constructed a strain with reporters for both σB, PsigB-YFP, and an early sporulation gene—spoIID (PspoIID-CFP)54. CFP illumination caused significant phototoxicity during time-lapse imaging of developing biofilms, so we reverted to examining snapshots of expression from biofilm slices. We found that σB and sporulation activity are anti-correlated at the cellular level (Fig. 5b, c), with cells that have activated σB to high levels having lower levels of PspoIID-CFP expression (best fit slope of −0.31). This was not apparent if the values of PspoIID-CFP and PsigB-YFP were randomly shuffled (best fit slope of 0) (Supplementary Fig. 9), confirming that the pathways are anticorrelated rather than just not correlated.

a The wild type gradients of σB (the ratio of PsigB-YFP to PsigA-RFP, n = 24 from five experiments) and spore density (calculated from cells expressing late stage sporulation marker, PsspB-YFP, n = 11 from four experiments). Error bars indicate the SEM. b Representative image showing coexistence of sporulating cells and σB expressing cells at the top of the biofilm. Green channel is PsigB-YFP, blue channel is PspoIID-CFP, red channel is PsigA-RFP. The top of the biofilm is at the top of the image. Scale bar is 5 μm. c Bivariate histogram showing the frequency of cells co-expressing PsigB-YFP and PspoIID-CFP. The fluorescent values are mean normalised for each image. The data represent two tilescan images, each covering ~3 mm of biofilm, from two different experiments and 372,689 cells. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Given the anti-correlation between cells entering sporulation and cells activating the general stress response (see Supplementary Fig. 9), we hypothesised that the pulsed expression of σB allows the coexistence of both transcriptional states at the top of the biofilm (Fig. 5a, b). Due to the long-tailed distribution of σB expression values (Fig. 3), only a fraction of cells exist in the high σB and low PspoIID-CFP expression state (Fig. 5) at any one time. This suggests that pulsed σB expression allows a fraction of cells to enter the high σB state without shutting off sporulation in all cells, which would occur if σB was expressed in a non-pulsatile manner to a high level in all cells at the top of the biofilm. Deleting σB resulted in a qualitatively similar sporulation gradient as compared to WT, confirming that the pulsing of σB allows a proportion of cells to have levels of σB that repress sporulation without interfering with the overall pattern of sporulation in the biofilm (Supplementary Fig. 10). To investigate further the functional role of pulsed gene expression in biofilm pattern formation, we developed a simple stochastic model of two pulsing regulators for sporulation (A) and σB (B), with one (B) able to block transcription of the other (A), with A leading to sporulation (Fig. 6a). Both pathways were assumed to pulse, as the sporulation pathway has also been observed to pulse in microcolonies grown on agarose pads55,56,57,58.

a Model network diagram. b Example traces of species a and b exhibiting pulses at the top (distance 0) of the simulated biofilm. The grey dashed line is the spore threshold (set at 1 for these parameters. A cell must express A for more than 30 simulated minutes above the threshold value to become a spore. For details see the “Methods” section). c Fraction of simulations where the value of species A exceeded the spore threshold for more than 30 simulated minutes where the B pulse frequency parameter sB = 0.25 and with the pulse frequency doubled 2 × sB = 0.5. The A pulse frequency parameter is set to sA = 0.7. d Shows the mean final value of species B, recorded from 10,000 simulations for sB = 0.25 and 2 × sB = 0.5. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We tested how the pulsed activation of two competing pathways affected cell fate in our model, and how these effects could be modulated by spatial signals. In our model, the frequency of stochastic pulses of activity is determined by a gradient representing “stress”, where the pulse frequencies of A and B are scaled independently from each other along this gradient. The finite duration of the pulses allows each system the opportunity to be dominant for a period of time. We observed a gradient of both A and B species that rose up the stress gradient (Fig. 6c, d), as observed experimentally for sporulation and for the general stress response (Fig. 5a). We then tested the effects of modulating pulse frequency of the repressor B on the sporulation gradient. Doubling the pulse frequency of B at all points along the gradient caused the peak of sporulation to be shifted away from the top (Fig. 6c), due to the increased repression of the sporulation pathway.

We tested the model prediction that increasing σB activity should alter the gradient of spores in the biofilm by inserting an additional copy of the genes (rsbQ-rsbP) controlling the energy stress pathway (2 × rsbQP). We did this as increasing phosphatase levels was previously shown to increase σB pulsing activity in microcolonies30). We made two such strains, one with a reporter for σB (PsigB-YFP), and another with a reporter for late stage sporulation (PsspB-YFP) (see the “Methods” section). We examined the effect of increasing RsbQP copy number on the σB gradient, and on the distribution of spore forming locations. As previously observed in liquid culture30, we observed higher single cell σB expression in the 2 × rsbQP strain than WT, with the single cell distributions remaining heterogeneous, characteristic of pulsing. Pulsing could also still be observed in timelapse movies of a ΔrsbRU 2 × rsbQP strain (Supplementary Movie 3). We then addressed the effects of the higher σB activity during biofilm formation. The 2 × rsbQP strain has a much stronger σB gradient than WT (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Fig. 11A) and more extreme heterogeneity in σB expression (Supplementary Fig. 11B). In 2 × rsbQP the spore forming region is shifted away from the top of the biofilm (Fig. 7a, d) compared to WT (Fig. 7a, c), confirming that σB is repressing sporulation in biofilms, and that pulsing of σB in WT cells allows the coexistence of both cell states.

a Spore density at the top of biofilm colonies in WT and 2 × rsbQP strains. The graph represents a ratio of amount of cells identified as spores (by expression of the PsspB-YFP fluorescent marker) to the combined amount of all cells expressing PsigA-RFP and spores (see the section “Methods” for details of quantification). For WT, data is replotted from Fig. 5a, n = 11 from four experiments, for 2 × rsbQP data, n = 12 from four experiments. Error bars represent SEM. b Doubling of rsbQP gene copy number increases and sharpens σB expression gradient in biofilm colonies. The graph represents a ratio of PsigB-YFP to PsigA-RFP expression in WT (black) and 2 × rsbQP (brown) backgrounds in biofilm colonies as measured from the distance from the colony top. (WT data n = 13 from three experiments, 2 × rsbQP n = 7 from 1 experiment). Error bars show the SEM. Scale bars are 25 μm. c, d representative images of the spore pattern in a WT and 2 × rsbQP biofilm respectively, PsigA-RFP in red and PsspB-YFP in cyan. All samples are from the central part of the biofilm and collected at 48 h after inoculation. Note that in c, between the biofilm and agar, is a layer of spores. This is typical of WT biofilms and is not reflected in the spore gradient a since there are no cells to compute a ratio. The full context for c and d is shown in Supplementary Fig. 12. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Our quantitative single cell microscopy has revealed how B. subtilis can use dynamic gene expression to generate spatial patterns of cell states. Using a fluorescent reporter for σB expression we found that σB is expressed heterogeneously throughout biofilm development (Fig. 3) and by tracking single cells during biofilm development we observed that this heterogeneous expression is generated by the pulsing on and off of σB (Figs. 4 and 1). σB activity, dependent on the energy stress pathway, is present as a gradient, with the highest levels at the top of the biofilm. We also found a gradient of spore density that is similar to the σB gradient (Fig. 5b), even though sporulation is repressed by σB activity. Modelling and experiment suggest that pulsed activation of σB allows these two mutually exclusive states to exist in the same layer of the biofilm, pointing to a function for noisy gene regulation in biofilm formation.

Gradients of nutrients59 and oxygen22,60 in biofilms have been observed in many species of bacteria61, which can lead to gradients in gene expression38,59,62,63. We observe a gradient of σB activation, dependent on the energy stress pathway, at the top of the biofilm that could correspond to a gradient of nutrients that depletes near the top of the biofilm. Interestingly the general stress response regulator rpoS is activated only in the top half of E. coli biofilms38, and in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, heterogeneous levels of rpoS mRNA have been recorded in the top layers of the biofilm64. In future it will be important to see, at the single cell level, whether these pathways display significant heterogeneity, and whether a similar functional role for this heterogeneity, allowing multiple cell states to exist in the same layer of the biofilm, is apparent.

We were able to observe single cell σB dynamics both in microcolonies (Fig. 1) and in developing biofilms (Fig. 4). Our approach is complementary to recent single cell time-lapse analysis of bacterial biofilms based on microfluidic devices65,66,67. Microfluidic devices have advantages for examination of biofilm formation, including allowing constant environmental conditions and the easy manipulation of conditions. However, biofilms grown in these devices do not exhibit the full range of physiological phenotypes exhibited by biofilms grown on solid surfaces. Our novel single-cell time-lapse protocol allows gene expression dynamics to be tracked during biofilm growth on solid surfaces, and can be readily applied to other microbial pathways.

We were able to examine the dynamic interactions between σB and sporulation in a simple mathematical model (Fig. 6). The model qualitatively captures how pulsing of a repressor, in combination with a gradient of signal, can generate a simple spatial pattern. Going forward, it will be interesting to use such a model to test the differences between unidirectional coupling and a mutually repressive bistable switch circuit68. However, our model does not account for the complex interactions of biofilm growth, spatial signals, and the detailed mechanisms of the regulation of σB or sporulation. In future this conceptual model should be expanded to develop a mechanistic understanding of the interactions between σB and sporulation in biofilm formation, which can capture more detailed aspects of their interactions. It will also be important to examine how the pattern observed here can contribute to the fitness of the colony. For example, the top of the biofilm consisting of both a protected layer of σB active cells and spores could be important for efficient spore dispersal.

In computation, randomness or noise can be harnessed to compute a function more quickly or with a simpler algorithm69,70,71 than is possible in a deterministic setting. Here we observe noise operating at the single cell level to control the distribution of cell types. It will be interesting to test what range of patterns noisy systems can generate compared to deterministic systems and whether there is a fundamental advantage to noise in development.

Multiple regulatory pathways have been shown to be expressed heterogeneously in B. subtilis under planktonic growth conditions. In addition to the general stress response30 and sporulation29, these include competence27, motility, and matrix production28. Pulsing in several B. subtilis alternative sigma factors has also been observed under energy stress, potentially allowing time-sharing of RNA polymerase during planktonic growth44. In future it will be important to test whether such noisy gene regulation in other pathways plays a role in biofilm formation.

Methods

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions

Biofilm forming B. subtilis strains are derived from NCIB3610 obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center. Donor strains for reporter constructs are derivatives of 168 Marburg. The complete strain list is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Genomic integration of reporter sequences was achieved using the pLK plasmid as described in ref. 72. Briefly, the pLK plasmid (which encodes an IPTG inducible competence regulon) was introduced to the NCIB3610 strain by protoplast transformation. ComK expression was then induced in NCIB3610+pLK by 1 mM IPTG in the presence of the integrative plasmid vector or genomic DNA. Target integration was confirmed by antibiotic selection and PCR. The pLK plasmid is unstable at high temperatures and was cured by incubating the resulting strains at 50 °C for 8 h.

Alternatively reporter genes were transferred to NCIB3610 using SPP1 phage-mediated transduction73. Briefly, 200 μL of overnight culture of donor bacterial strain was added and incubated with phages in 200 μL TY (LB plus 10 mM MgSO4 and 1 μM MnSO4) for 15 min at 37 °C without shaking. Then cells with phage were mixed with 3 mL of melted top TY agar and poured onto a fresh TY plate and incubated until confluent lysis developed. 5 ml TY was added to each plate and the top agar layer containing phages was scrapped, collected, and centrifuged. Supernatant with phages was collected and filtered. Phages were stored at 4 °C. Recipient cells were grown overnight in TY at 37 °C and incubated with phages containing donor DNA for 30 min at 37 °C, media was removed by centrifugation, cells resuspended in TY and plated on TY plates with 10 mM sodium citrate and selective antibiotics. After O/N growth another round of antibiotic selection was performed and selected colonies were checked for proper DNA integrations.

Finally, we also transformed reporter strains into the easily transformable NCIB3610 background from the Kearns laboratory, which is identical to NCIB3610 except for a single point mutation, comI(Q12L) in an endogeneous plasmid that increases natural competence74. For detailed information regarding the construction of strains and plasmids used in this study, please see the Supplementary Methods.

For routine growth, cells were propagated in LB medium. When necessary, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: spectinomycin (100 μg mL−1), chloramphenicol (5 μg mL−1), kanamycin (10 μg mL−1), tetracycline (10 μg mL−1), and erythromycin (1.25 μg mL−1). For biofilm growth we used MSgg medium23,75 (5 mM potassium phosphate (pH = 7.0), 100 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (pH = 7.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 700 μM CaCl2, 50 μM MnCl2, 50 μM FeCl3, 1 μM ZnCl2, 0.5% glycerol, 2 μM thiamine–HCl, 0.5% potassium glutamate) fortified with 1.5% bacto agar (Fisher Scientific).

B. subtilis biofilm growth on A. thaliana roots assay

The experiments to show B. subtilis biofilm formation on plant roots were performed as described in ref. 49. Briefly, A. thaliana Col-0 seedlings were grown on \(\frac{1}{2}\) Murashige–Skoog medium (0.22% MS salts + vitamins (Duchefa M0222) supplemented with 0.8% plant agar, pH = 5.7–5.8) at 20 °C. Plants were grown in a 16:8 h light:dark cycle growth chamber for 6 days. Next, the seedlings were transferred to 300 μl of MSNg medium (5 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7; 0.1 M MOPS, pH 7; 2 mM MgCl2; 0.05 mM MnCl2; 1 mM ZnCl2; 2 μM thiamine HCl; 700 μM CaCl2; 0.2% NH4Cl supplemented with 0.05% glycerol) in 48-well plates. Medium with plants was inoculated with B. subtilis cells at OD 600 = 0.02. Plates with plants and bacteria were put on an orbital shaker at 100 rpm and incubated in the same plant growth chamber for 48 h. Plant roots were subjected to confocal microscopy directly after that.

Biofilm growth, sample collection, and thin sectioning

To prepare thin slices for imaging, biofilm colonies were grown as follows: cells were scraped from an overnight LB plate and re-suspended in LB medium to A600 = 1.0 optical units. 2 μL of cell suspension was put on the surface of an MSgg agar plate. Biofilm colonies were collected at 24, 36, 48, 72, and 96 h after incubation at 30 °C and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen overlaid with Tissue-Tec O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, ref 4583) in custom foil moulds and kept at −80 °C. 8 μm thin slices were made using a Leica CM3050S cryomicrotome, collected on SuperFrost Plus microscope slides (VWR cat. no. 631-0108) and stored at −80 °C before use. For imaging, biofilm slices were overlaid with the mounting medium (0.5% N-propyl gallate, 50% glycerol and PBS (pH 7.4))24.

Agarose pad time-lapse microscopy

Time-lapse imaging of single bacterial cells was performed as described in refs. 30,76. Cells were grown overnight on LB plates with appropriate antibiotics. Then cells were diluted to A600 = 0.01 in MSgg and 2 μL of this suspension was spotted on low melting temperature agarose pads made with 1:100 MSgg diluted in water. Cells were imaged with a Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope using a CFI Plan Apo DM Lambda ×100 oil objective (N.A. = 1.45), a Photometerics Coolsnap HQ2 camera, and using an automated time-lapse imaging platform. Time-lapse images were taken every 10 min for 10 h and were processed and analysed using Schnitzcells76. Movies were not analysed if they were out of focus, if the cells piled vertically too early, or if cells grew too slowly. Individual cells that behaved unusually, (e.g. stopping growth or lysing) were excluded from the analysis. When analysing single cell data we discard data from the first frames of the movie (before 8 cells) to allow cells to adjust to growth on the agarose pads and to avoid inclusion of cells with fluorescent protein levels that could reflect the previous plankonic growth or the transition to the agarose pad.

Thin slice imaging

Imaging of biofilm slices (Fig. 2) with fluorescent reporters was performed using a Zeiss LSM780 laser scanning confocal microscope with a dry 10x Plan Apochromat (NA 0.45). Images were acquired using sequential imaging and saved as 16 bit images with 1 pixel representing 0.59 μm. For single cell imaging with three fluorescent reporters (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 9) we used an oil immersion ×63 Plan Apochromat (NA 1.4) objective. We used the LSM780 built-in linear unmixing feature of the confocal microscope to reduce bleed-through of signal.

For single cell imaging of biofilm slices (Figs. 3, 11 and Supplementary Figs. 5, 6) we used a Zeiss LSM700 with an oil immersion ×63 Plan Apochromat (NA 1.4) objective. Images were acquired using sequential imaging with a 488 nm laser at 2% power and a 555 nm laser at 2% power. The pinhole was 47 μm for both channels. Images were stored as 16 bit images with 1 pixel representing 0.05 μm. The beam splitter for the yellow channel was MBS 405/488/555/639 DBS1: 550 nm, and for the red channel MBS 405/488/555/639 DBS1: 600 nm. To quantify sporulation (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figs. 10 and 12) we made long tilescans of biofilm slices. Regions of biofilm were excluded from analysis if they were physically damaged during sectioning. We also excluded regions where the biofilm folded over on itself or where the top was not easily discernible.

Images were analysed using custom software. Due to decreasing cell density there is ambiguity as to where the biofilm starts at the air interface, this interferes with spore density calculations so we discard the top 2 μm of all biofilm gradient data.

The LSM700 was also used to capture the live biofilm images with single cell resolution in Supplementary Figs. 8 and 4 using the above settings. For the live biofilm gradients in Supplementary Fig. 8 we used the LSM700 with the same settings but with a dry ×20 Plan Apochromat (NA 0.8) objective with the pinhole for the 555 nm laser at 33.40 μm and for the 488 nm laser the pinhole was at 34.52 μm. Images were acquired using sequential mode and saved as 16 bit images with 1 pixel covering 0.31 μm.

Images were discarded if the live cells moved between sequential red/yellow laser scans. Images were also excluded from analysis if they contained very few cells or were mostly spores rather than live cells. The cells from this dataset (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 8) exhibited a bimodal pattern of red channel (constitutive PsigA-RFP) intensity. We concluded, on visual inspection, that the fainter population were cells in a different focal plane. We exclude these out of plane cells by only considering cells with mean cell red intensity >6800. We chose this value by fitting two Guassian distributions to the bimodal populations, the threshold value is the mean minus the standard deviation of the brighter population of cells.

Imaging of live biofilm development

To grow colonies suitable for live time lapse confocal imaging we first filled 50 mm glass bottomed dishes (Wilco Wells HBST-5040) with 9 mL of MSgg agar (described above). The dishes were left closed over night at room temperature, then stored at 4 °C. Before inoculation, we cut the agar into two segments, dividing the agar into approximately one-third and two-thirds. The cut was made perpendicular to the glass bottom. The larger segment of agar was removed and transferred to a fresh glass bottomed dish to reduce the amount of residual media on the glass surface. We prepared A600 = 1.0 optical units of cell suspension and inoculated the the agar and glass interface with three, evenly distributed, 1.2 μL drops of cell suspension and left to dry for 10 min. The dish was closed and incubated at 30 °C with the dish standing upright and the inoculated surface kept horizontal. After 7 h the dish was wrapped with Parafilm and placed into the microscope for imaging.

To record the development of live biofilm growth we used a Leica TCS SP8 DIM8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, UK) fitted with HyD SMD detectors and equipped with solid-state lasers, 448 nm for CFP, 514 nm for YFP, and 552 nm for RFP.

A HC PL APO CS2 ×100 1.44NA oil immersion objective (Leica order number 11506325) was used with the digital zoom set to 1.5. We used line sequential bi-directional scanning with speed 200 Hz and a line average of 3 was used for RFP and 2 for YFP. The pinhole was set to 1.0 Airy units. Images were recorded as 12 bit images. The hardware autofocus was set on an empty region of the dish near to the positions imaged. The stage was contained in a temperature controlled case kept at 30 °C. The objective was cooled using the built in liquid cooling system to keep it at 28 °C.

Fluorescent protein bleed through and background subtraction

For all datasets we corrected for the mean background signal recorded by the microscopes. For the agarose pad time-lapse images this represents the background signal of the agar and media. For the low magnification biofilm cryosections it represents the background signal of the cryostat specimen matrix. For the high magnification cryosections it represents the cryostat specimen matrix and mounting medium.

For the low and high magnification biofilm cryosections we also calculated the contribution of the cell’s natural autofluorescence (using the strain NCIB3610 with no fluorescent reporters) and bleed-through caused by activation of the RFP protein by the 512 nm laser (using the PsigA-RFP reporter strain with no YFP reporter). The difference between NCIB3610 autofluorescence in the yellow channel and the mean yellow channel signal of an RFP only strain was used to quantify the bleed-through of the RFP protein into the YFP channel. For the high magnification images the bleed-through accounts for 6% of the YFP signal in the top of 20 μm of the central part of the WT biofilm at the 72 h time point. For the low magnification images the bleed-through accounts for 1.5% of the YFP signal in the top of 20 μm of the central part of the WT biofilm at the 72 h time point.

Low magnification σ B gradients

We extracted fluorescence gradients from confocal images of thin cryoslices of biofilm. The biofilm was identified in the red channel where cells were constitutively expressing PsigA-RFP. The biofilm was segmented using custom Python software and the Scikit-Image package77. The biofilm is easily isolated with an Otzu threshold, however, this initial mask contained long strips of auto-fluorescent agar. To remove the agar we breakup the mask into sub-segments with similar values using a watershed segmentation with local maxima as seeds. We then erode the resulting over-segmentation with a circular selection element with a radius large enough to remove the sub-segments of auto-fluorescent agar (in our case 25 pixels). Any segments that are totally removed by the erosion are assumed to be agar and not restored, any other segments are restored to their pre-erosion shape. All contiguous segments are re-joined into a single biofilm mask. Any segments with area <10% of the image are removed and assumed to be artifacts of cryosectioning.

Single cell and spore segmentation

To segment both individual cells and individual spores from high magnification confocal images we used custom Python software and the Scikit-Image package77. The input images were either constitutive PsigA-RFP for cells or a late stage sporulation PsspB-YFP reporter.

Spore density

To quantify spore density we used tile-scan confocal images of the central section of the biofilm with single cell and spore resolution. For each image we calculated the number of spores and the number of cells in each depth bin d ± 1 μm, for each d sampled every 0.5 from 2 μm from the top of the biofilm to 140 μm. Then we plot either the ratio of spores to the combined number of cells and spores in each bin (see Fig. 7), or we scale the spore counts in each bin by the number of image pixels in that bin (see Supplementary Fig. 10B).

Model details

To explore the interactions of the σB and the sporulation pathways, we used a qualitative model that produces stochastic pulses. Note that we do not attempt to model the biochemical processes that lead to the generation of σB or sporulation pulses55,56,57,58. Instead, we use a variation of the well studied68 two-step transcription–translation gene expression model used to study stochastic cell decision making and mutual inhibition. System A is reaction (1) to reaction (4), and system B is reaction (5) to reaction (8). Interaction between the two systems occurs in reaction (9) with B blocking the pulse initiation of A.

The full reaction network is as follows:

where GX, RX, X represent the “gene”, “mRNA” and “protein” of X ∈ {A, B}.

The time scale of the model is in seconds. We modified the equations and parameters from those used previously to examine bistable switches68. The parameters β, δ, ϵ, bB, and uB are unchanged from ref. 68 and are estimations of the rate of the biological processes they represent. To avoid bistability, we lower the transcription rates ζsA and ζsB. The parameters sA, sB and ζ are chosen so that A with reaction (1) at rate ζsA and reaction (5) at rate 2sBζ for high ζ (high stress) are below the point where system A dominates (simulations always produce a spore) or system B dominates (simulations never produce a spore). At high and low ζ, both species are still exhibiting pulsatile expression. The full list of parameters can be seen in Table 1.

Simulations used the Doob–Gillespie stochastic simulation algorithm78. Simulations were run from initial conditions where all species were absent except GA = GB = 1. Each simulation was allowed to run for 6.5 simulation minutes were discarded to ensure the system was out of the transient phase. To simulate the effect of the stress gradient we set ζ = 10g, where g is one of 20 evenly sampled points from the interval [\({\mathrm{log}}_{10}\) 5 × 10−5, \({\mathrm{log}}_{10}\) 5 × 10−3] representing the bottom (5 × 10−5) and top (5 × 10−3) of the biofilm. For each ζ we ran 10,000 simulations. For each simulation we recorded both: the final B value and the longest duration species A spent above a threshold θ = 1. The threshold θ is the 20th percentile value of steady-state distribution of A when GB = 0 (estimated using the Γ distribution approximation of this system79) and scales with the rise in pulse initiation rate which allows us to detect pulses at low initiation rates and in high initiation rates. For all the parameters used in this paper θ = 1. A simulation is judged to have produced a spore if the longest duration A was above its threshold is >30 simulated minutes.

Data availability

Confocal images are available on request to the authors. The quantification of the confocal images are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3544513.

Code availability

The analysis code and simulation code developed for this project is available at https://gitlab.com/slcu/teamJL/nadezhdin_murphy_et_al_2019.

References

Gilbert, S. F. & Barresi, M. J. F. Developmental Biology, 11th edn (Sinauer Associates Inc., 2016, ISBN 978-1605356044).

Morelli, L. G., Uriu, K., Ares, S. & Oates, A. C. Computational approaches to developmental patterning. Science 336, 187–191 (2012).

Wolpert, L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J. Theor. Biol. 25, 1–47 (1969).

Ibañes, M. & Izpisúa Belmonte, J. C. Theoretical and experimental approaches to understand morphogen gradients. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 176 (2008).

Wernet, M. F. et al. Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nature 440, 174–180 (2006).

Meyer, H. M. et al. Fluctuations of the transcription factor ATML1 generate the pattern of giant cells in the Arabidopsis sepal. eLife 6, e19131 (2017).

Collier, J. R., Monk, N. A., Maini, P. K. & Lewis, J. H. Pattern formation by lateral inhibition with feedback: a mathematical model of delta-notch intercellular signalling. J. Theor. Biol. 183, 429–446 (1996).

Turing, A. M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 237, 37–72 (1952).

Gierer, A. & Meinhardt, H. A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik 12, 30–39 (1972).

Cai, L., Friedman, N. & Xie, X. S. Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature 440, 358–362 (2006).

Golding, I., Paulsson, J., Zawilski, S. M. & Cox, E. C. Real-time kinetics of gene activity in individual bacteria. Cell 123, 1025–1036 (2005).

Levine, J. H., Lin, Y. & Elowitz, M. B. Functional roles of pulsing in genetic circuits. Science 342, 1193–200 (2013).

Veening, J.-W., Smits, W. K. & Kuipers, O. P. Bistability, epigenetics, and bet-hedging in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62, 193–210 (2008).

Lewis, K. Persister cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 357–372 (2010).

Harms, A., Maisonneuve, E. & Gerdes, K. Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science 354, aaf4268-1–aaf4268-1 (2016).

Eldar, A. & Elowitz, M. B. Functional roles for noise in genetic circuits. Nature 467, 167–173 (2010).

Vlamakis, H., Chai, Y., Beauregard, P., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Sticking together: building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 157–168 (2013).

Flemming, H.-C. et al. Biofilms: an emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 563–575 (2016).

Mielich-Süss, B. & Lopez, D. Molecular mechanisms involved in Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 555–565 (2015).

Wilking, J. N. et al. Liquid transport facilitated by channels in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 848–852 (2013).

Hobley, L. et al. BslA is a self-assembling bacterial hydrophobin that coats the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13600–13605 (2013).

Arnaouteli, S. et al. Bifunctionality of a biofilm matrix protein controlled by redox state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E6184–E6191 (2017).

Branda, S. S., González-Pastor, J. E., Ben-Yehuda, S., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Fruiting body formation by Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11621–11626 (2001).

Vlamakis, H., Aguilar, C., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Control of cell fate by the formation of an architecturally complex bacterial community. Genes Dev. 22, 945–953 (2008).

Lopez, D., Vlamakis, H. & Kolter, R. Generation of multiple cell types in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 152–163 (2009).

van Gestel, J., Vlamakis, H. & Kolter, R. From cell differentiation to cell collectives: Bacillus subtilis uses division of labor to migrate. PLOS Biol. 13, e1002141 (2015).

Süel, G. M., Kulkarni, R. P., Dworkin, J., Garcia-Ojalvo, J. & Elowitz, M. B. Tunability and noise dependence in differentiation dynamics. Science 315, 1716–1719 (2007).

Norman, T. M., Lord, N. D., Paulsson, J. & Losick, R. Memory and modularity in cell-fate decision making. Nature 503, 481–6 (2013).

Russell, J. R., Cabeen, M. T., Wiggins, P. A., Paulsson, J. & Losick, R. Noise in a phosphorelay drives stochastic entry into sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 36, 2856–2869 (2017).

Locke, J. C. W., Young, J. W., Fontes, M., Jiménez, M. J. H. & Elowitz, M. B. Stochastic pulse regulation in bacterial stress response. Science 334, 366–369 (2011).

Gruber, T. M. & Gross, C. A. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 441–66 (2003).

Hecker, M., Pané-Farré, J. & Völker, U. SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and related Gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 215–236 (2007).

Young, J. W., Locke, J. C. W. & Elowitz, M. B. Rate of environmental change determines stress response specificity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4140–4145 (2013).

Reder, A., Albrecht, D., Gerth, U. & Hecker, M. Cross-talk between the general stress response and sporulation initiation in Bacillus subtilis - the σ B promoter of spo0E represents an AND-gate. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2741–2756 (2012a).

Reder, A., Gerth, U. & Hecker, M. Integration of σ B activity into the decision-making process of sporulation initiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 194, 1065–1074 (2012b).

Rothstein, D. M., Lazinski, D., Osburne, M. S. & Sonenshein, A. L. A mutation in the Bacillus subtilis rsbU gene that limits RNA synthesis during sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 199, e19131 (2017).

Marles-Wright, J. & Lewis, R. J. Stress responses of bacteria. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 755–760 (2007).

Serra, D. O. & Hengge, R. Stress responses go three dimensional - the spatial order of physiological differentiation in bacterial macrocolony biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 1455–1471 (2014).

Rani, S. A. et al. Spatial patterns of DNA replication, protein synthesis, and oxygen concentration within bacterial biofilms reveal diverse physiological states. J. Bacteriol. 189, 4223–4233 (2007).

Nadezhdin, E. V., Brody, M. S. & Price, C. W. An α/β hydrolase and associated Per-ARNT-Sim domain comprise a bipartite sensing module coupled with diverse output domains. PLoS ONE 6, e25418 (2011).

Brody, M. S., Vijay, K. & Price, C. W. Catalytic function of an α/β hydrolase is required for energy stress activation of the ς b transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6422–6428 (2001).

Marles-Wright, J. et al. Molecular architecture of the “stressosome”, a signal integration and transduction hub. Science 322, 92–96 (2008).

Alper, S., Dufour, A., Garsin, D. A., Duncan, L. & Losick, R. Role of adenosine nucleotides in the regulation of a stress-response transcription factor in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 260, 165–177 (1996).

Park, J. et al. Molecular time sharing through dynamic pulsing in single cells. Cell Syst. 6, 216–229.e15 (2018).

Cabeen, M. T., Russell, J. R., Paulsson, J. & Losick, R. Use of a microfluidic platform to uncover basic features of energy and environmental stress responses in individual cells of Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006901 (2017).

Cao, M., Wang, T., Ye, R. & Helmann, J. D. Antibiotics that inhibit cell wall biosynthesis induce expression of the Bacillus subtilis σ W and σ M regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1267–1276 (2002).

Butcher, B. G. & Helmann, J. D. Identification of Bacillus subtilis sigma-dependent genes that provide intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacilli. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 765–782 (2006).

Helmann, J. D. Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 30, 122–132 (2016).

Beauregard, P. B., Chai, Y., Vlamakis, H., Losick, R. & Kolter, R. Bacillus subtilis biofilm induction by plant polysaccharides. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1621–30 (2013).

Avila-Pérez, M., Hellingwerf, K. J. & Kort, R. Blue light activates the σ B -dependent stress response of Bacillus subtilis via YtvA. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6411–6414 (2006).

Akbar, S. & Price, C. W. Isolation and characterization of csbB, a gene controlled by Bacillus subtilis general stress transcription factor σ B. Gene 177, 123–128 (1996).

Höper, D., Völker, U. & Hecker, M. Comprehensive characterization of the contribution of individual SigB-dependent general stress genes to stress resistance of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 187, 2810–2826 (2005).

Setlow, P. Small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus species: structure, synthesis, genetics, function, and degradation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42, 319–338 (1988).

Steil, L., Serrano, M., Henriques, A. O. & Völker, U. Genome-wide analysis of temporally regulated and compartment-specific gene expression in sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 151, 399–420 (2005).

Kuchina, A., Espinar, L., Garcia-Ojalvo, J. & Süel, G. M. Reversible and noisy progression towards a commitment point enables adaptable and reliable cellular decision-making. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002273 (2011a).

Kuchina, A. et al. Temporal competition between differentiation programs determines cell fate choice. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 557 (2011b).

Levine, J. H., Fontes, M. E., Dworkin, J. & Elowitz, M. B. Pulsed feedback defers cellular differentiation. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001252 (2012).

Narula, J. et al. Chromosomal arrangement of phosphorelay genes couples sporulation and DNA replication. Cell 162, 328–337 (2015).

Huang, C.-T., Xu, K. D., McFeters, G. A. & Stewart, P. S. Spatial patterns of alkaline phosphatase expression within bacterial colonies and biofilms in response to phosphate starvation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 1526–1531 (1998).

Xu, K. D., Stewart, P. S., Xia, F., Huang, C.-T. & McFeters, G. A. Spatial physiological heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm is determined by oxygen availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 4035–4039 (1998).

Stewart, P. S. & Franklin, M. J. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 199–210 (2008).

Williamson, K. S. et al. Heterogeneity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms includes expression of ribosome hibernation factors in the antibiotic-tolerant subpopulation and hypoxia-induced stress response in the metabolically active population. J. Bacteriol. 194, 2062–2073 (2012).

Werner, E. et al. Stratified growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 6188–6196 (2004).

Pérez-Osorio, A. C., Williamson, K. S. & Franklin, M. J. Heterogeneous rpoS and rhlR mRNA levels and 16S rRNA/rDNA (rRNA gene) ratios within Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, sampled by laser capture microdissection. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2991–3000 (2010).

Liu, J. et al. Metabolic co-dependence gives rise to collective oscillations within biofilms. Nature 523, 550–554 (2015).

Drescher, K. et al. Architectural transitions in Vibrio cholerae biofilms at single-cell resolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E2066–E2072 (2016).

Yan, J., Sharo, A. G., Stone, H. A., Wingreen, N. S. & Bassler, B. L. Vibrio cholerae biofilm growth program and architecture revealed by single-cell live imaging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E5337–E5343 (2016).

Strasser, M., Theis, F. J. & Marr, C. Stability and multiattractor dynamics of a toggle switch based on a two-stage model of stochastic gene expression. Biophys. J. 102, 19–29 (2012).

Murphy, N., Petersen, R., Phillips, A., Yordanov, B. & Dalchau, N. Synthesising and tuning chemical reaction networks with specified behaviours. J. R. Soc. Interface 15, 16–33 (2018).

Thubagere, A. J. et al. A cargo-sorting DNA robot. Science 357, eaan6558 (2017).

Adleman, L. & Huang, M. Recognizing primes in random polynomial time. Alfred V. Aho (ed.). In STOC’87 19th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, (ACM, 1987).

Nijland, R., Burgess, J. G., Errington, J. & Veening, J. W. Transformation of environmental Bacillus subtilis isolates by transiently inducing genetic competence. PLoS ONE 5, 1–7 (2010).

Kearns, D. B. & Losick, R. Swarming motility in undomesticated Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 49, 581–590 (2003).

Konkol, M. A., Blair, K. M. & Kearns, D. B. Plasmid-encoded ComI inhibits competence in the ancestral 3610 strain of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 195, 4085–4093 (2013).

Asally, M. et al. Localized cell death focuses mechanical forces during 3D patterning in a biofilm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18891–18896 (2012).

Young, J. W. et al. Measuring single-cell gene expression dynamics in bacteria using fluorescence time-lapse microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 7, 80–88 (2012).

van der Walt, S. et al. the scikit-image contributors. scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Gillespie, D. T. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J. Phys. Chem. 81, 2340–2361 (1977).

Friedman, N., Cai, L. & Xie, X. S. Linking stochastic dynamics to population distribution: an analytical framework of gene expression. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 168302 (2006).

Acknowledgements

Dr. Avigdor Eldar (Tel-Aviv University) for the B. subtilis PspoIID-CFP reporter strain. Dr. Nicola Stanley-Wall (The University of Dundee) for providing SPP1 phage culture and help and advise with the transduction protocol. Cambridge Advanced Imaging Centre for the assistance with samples preparation. Thanks to Dr. Raymond Wightman for extensive advice, troubleshooting, and help to capture timelapse confocal images of living biofilms.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.N., N.M., J.C.W.L. conceived and designed the study. E.N., N.M., J.C.W.L., and A.P. analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the article. E.N. constructed strains and performed the experiments. E.N. and N.M. developed the live biofilm imaging assay. N.M. implemented the model with input from A.P. and N.D. All authors provided input into the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jonathan Dworkin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source Data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadezhdin, E., Murphy, N., Dalchau, N. et al. Stochastic pulsing of gene expression enables the generation of spatial patterns in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. Nat Commun 11, 950 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14431-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14431-9

This article is cited by

-

Spatial transcriptome uncovers rich coordination of metabolism in E. coli K12 biofilm

Nature Chemical Biology (2023)

-

Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation and social interactions

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.