Abstract

D-cycloserine is an antibiotic which targets sequential bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan biosynthesis enzymes: alanine racemase and D-alanine:D-alanine ligase. By a combination of structural, chemical and mechanistic studies here we show that the inhibition of D-alanine:D-alanine ligase by the antibiotic D-cycloserine proceeds via a distinct phosphorylated form of the drug. This mechanistic insight reveals a bimodal mechanism of action for a single antibiotic on different enzyme targets and has significance for the design of future inhibitor molecules based on this chemical structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increased incidence and dissemination of microbial resistance to antimicrobials, the lack of incentive for development of these drugs in the pharmaceutical sector and the relative failure of high throughput approaches in the discovery of new antimicrobial targets, all point to a growing crisis in treating infectious diseases1,2. It is clear that many of the most highly successful antibacterial agents target multiple activities in bacterial metabolism, resulting in cellular responses leading to cessation of growth or cell lysis3,4. This makes the re-evaluation and further exploration of established antimicrobial targets and natural sources of antibiotics that target them, a potentially powerful approach to future antibacterial development.

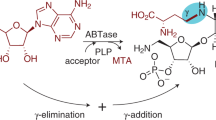

D-cycloserine (DCS) has been long known to have antibacterial properties and is unusual in respect of multi-targeting, since it is known to inhibit two sequential enzymes in the bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway, leading to the formation of the dipeptide D-alanyl-D-alanine (D-Ala-D-Ala)5. DCS targets alanine racemase (Alr), leading to the formation of an aromatized DCS-PLP adduct, which irreversibly blocks Alr activity6. In addition, DCS also targets the next enzyme in the pathway, D-Ala-D-Ala ligase (Ddl). DCS inhibition of Ddl was thought to be by simple, competitive and reversible binding to one of the D-Ala binding sites5 on this enzyme. The bacterial targets of DCS inhibition in mycobacteria have been recently shown by metabolomics to be both Ddl and Alr but predominantly via the former enzyme7. DCS is a natural product of Streptomyces garyphalus and S. lavendulae and is a structural analog of D-Ala. Its clinical use at present is limited to the treatment of tuberculosis (TB), where it is used as a second-line drug for multidrug resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Its utility is limited as DCS is also a co-agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor in the brain. DCS binds to the glycine modulatory site of the NMDA receptor and causes adverse side effects, including seizures and peripheral neuropathy8. These rare but serious side effects limit its use as an antibiotic to all but the most recalcitrant M. tuberculosis infections and preclude its more general use as an antimicrobial agent. However, oral bioavailability, its general efficacy, high gastric tolerance, low rates of resistance and lack of cross reactivity to other anti-TB drugs mean it is still of considerable interest and potential.

Ddl enzymes present an attractive target for further chemotherapeutic investigation because of their essential and universal role in bacterial cell-wall peptidoglycan biosynthesis, which has been a validated target for antibiotics since the discovery of penicillin. Ddls, which belong to the ATP grasp superfamily, use ATP to activate a single D-alanine substrate. Phosphorylation of D-alanine by the bound ATP (Supplementary Fig. 1) produces a transient phosphoryl carboxylate intermediate susceptible to nucleophilic attack by a second D-amino acid. The resulting dipeptide is then incorporated onto the tripeptide chain of the peptidoglycan by the next enzyme in the cytoplasmic phase of the peptidoglycan biosynthetic pathway9. Additional interest in Ddl enzymes arises with altered second-substrate specificity of the vancomycin associated Ddl ligases (e.g., VanA, VanB, VanC), which are the central components in the resistance mechanism9 and have been recently shown to have been present in the ecosystem for millennia10. Although the interaction of DCS with Alr has been thoroughly studied, no comparable structural data has yet been obtained to show how DCS interacts with Ddls. We set out therefore to investigate this by elucidation of Ddl structures in complex with DCS and natural ligands to provide further mechanistic insight into the mode of inhibition. Our results reveal the presence of phosphorylated DCS and ADP in both active sites within a dimer. These results are confirmed “off-crystal” using positional isotope exchange and ATPase inhibition assays. Importantly, calculations indicate that DCSP would not bind to the human NMDS receptor, which is the main cause of its toxicity. DCSP-inhibited EcDdlB represents a significant advance on the mechanism-of-action of this clinically used antibiotic and paves for the development of further improved analogs to target Ddl enzymes.

Results

Structure of inhibited EcDdlB reveals phosphorylated DCS

E. coli DdlB (EcDdlB) was co-crystallized, as described in methods, with ATP and D-Ala-D-Ala (Fig. 1a), ADP and D-Ala-D-Ala (Fig. 1b), and ATP and DCS (Fig. 1c) and structures determined at sub 2 Å resolution as summarized in Table 1. The overall structure is described in Supplementary Fig 2. Weighted difference maps at 1.65 Å resolution revealed the surprising discovery that phosphorylated DCS was bound in the high-affinity D-alanine binding site (D-Ala1), with the γ-5′-phosphoryl moiety of ATP having been transferred to the 3-oxygen of DCS (Fig. 1c). Continuous strong electron density extended from the DCS oxygen into the phosphoryl group, which was then linked by two magnesium ions to the product ADP. This finding revealed the existence of a new chemical entity, DCSP, within this inhibited EcDdlB structure. The DCSP moiety mimics the structure of D-alanyl phosphate, which is an obligatory intermediate formed by phosphoryl transfer during the first stage of catalysis, prior to condensation with the C-terminal D-Ala of the D-Ala-D-Ala product of DdlB. DCSP exploits most of the interactions that generate the high affinity site for the first D-Ala substrate (D-Ala1). The amino group of DCSP forms a strong hydrogen bond with the carboxylate group of Glu-15, mimicking the critical interaction made by the α-amino group of D-Ala in the first subsite. The ring oxygen (position 1) of DCSP is hydrogen bonded to the backbone NH of Gly-276, in the oxyanion pocket of DdlB, while the adjacent non-protonated ring nitrogen, which occupies the position of the peptide oxygen of the dipeptide D-Ala-D-Ala product mimics the bifurcated interactions with Gly-276 NH and Arg-255 NH1 made by this atom in the product complex. The DCSP phosphate group is hydrogen bonded to Arg-255 (NH1 and NH2), Lys-215 and the amide nitrogen of Ser-150, replicating the interactions observed with the γ-phosphate of ATP and it forms additional links with the adjacent ADP via two coordinated magnesium ions that bridge between the DCSP and ADP molecules.

Active site region of EcDdlB in different complexes. a Active site region of EcDdlB in complex with ATP and D-Ala-D-Ala, and (b) ADP, carbonate ion and D-Ala-D-Ala. c 2F o-F c difference map of EcDdlB in complex with ADP, 2Mg2+ and DCSP. Electron density at 2 σ is shown over the ADP, Mg2+ and DCSP atoms for clarity. EcDdlB residues Glu15 (above) and Arg255 (below) are within hydrogen bonding distance to DCSP

Positional isotope exchange shows DCSP formation in solution

To demonstrate the formation of DCSP by EcDdlB in solution a positional isotope exchange (PIX)11,12 experiment was setup using [γ-18O4]-ATP. Changes in the isotopic composition of the initial [γ-18O4]-ATP species over time were monitored by 31P NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 2). As described in the PIX reaction scheme (Fig. 2a), the reversible transfer of the γ-P group from [γ-18O4]-ATP to DCS (1 and 3) induces scrambling in the position of the β-γ bridging 18O and affects the isotopic composition at γ-P and β-P. This is caused by the free rotation of the β-P group of ADP with subsequent positional exchange of oxygens before the reverse reaction takes place (2). As a consequence, decrease of the [γ-18O4]-P species and concomitant increase of [γ-18O3 16O]-P species are observed in the NMR spectrum (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3a) as well as transfer of the β-γ bridge 18O to a non-bridging position, resulting in an upfield change of 31P chemical shift at the β-P position (Fig. 2c). No PIX reaction was observed in control experiments performed in absence of DCS at the same concentration of EcDdlB, confirming that DCS is the specific acceptor of the ATP γ-P group during the phosphate transfer reaction (Supplementary Fig. 4). A rate of 0.36 h−1 was obtained for the PIX reaction by fitting the decrease of the [γ-18O4]-P species fraction (Fig. 2e) to Eq. (1):

where, F is the fraction of γ-18O4-P scrambled, F 0 is the final exchange value of γ-18O4-P, A is the amplitude of change in γ-18O4-P observed during the experiment, k is the observed rate, and t is time. The PIX rate reaches a value of zero at around 8 h. Control experiments (Supplementary Fig. 3b) indicate that this decrease in PIX rate is due to isotopic equilibrium, which as DCS is an inhibitor, or very slow substrate in this particular case, is quite slow. Importantly, as identical PIX kinetics are observed in control experiments, where fresh labeled ATP was added after the equilibrium was achieved (Supplementary Fig. 3b), it is clear that the slowdown in PIX rate is not due to enzyme or substrate inactivation.

Mechanism of DCS phosphorylation by EcDdlB as proved by positional isotope exchange (PIX) and steady-state kinetics of ATP hydrolysis and its inhibition by DCS. a Positional isotope exchange (PIX) mechanism for inhibition of EcDdlB by DCS. Position of 18O label in the initial [γ-18O4]-ATP, intermediate and final species is highlighted in red. b 31P NMR spectra monitoring changes in the isotopic composition of γ-P (doublet), (c) β-P (triplet) and (d) α-P (doublet) species of [γ-18O4]-ATP as a function of time: (blue) 15 s, (red) 0.5 h, (green) 3.5 h, (purple) 5.5 h, (yellow) 8 h, (orange) 18 h. In accordance with the reaction scheme reported in a, a PIX effect is observed both at γ-P and β-P position whereas, as expected, α-P remains unaffected. Based on the relative peak intensity the initial fraction of the [γ-18O4]-P species (blue, upfield doublet) and [γ-18O3 16O]-P species (blue, downfield doublet) is 77% and 23%, respectively, consistent with a > 94% isotopic enrichment of each of the 4 oxygens. e Fractional occurrence of the [γ-18O4]-P species during the PIX reaction as a function of time. After 8 h upon addition of the enzyme at 25 °C, the fraction of the [γ-18O4]-P species decreased to 42%. The rate constant was obtained from fitting of the data to Eq. (1). f Phosphatase activity of EcDdlB (black) as a function of ATP concentration and its inhibition by 1 mM DCS (red) were monitored by a coupled enzyme system assay (See Methods for details). Points are experimental data and lines best fit to Eq. (2). g Inhibition of EcDdlB hydrolysis of ATP by DCS. Data were fitted to Eq. (3)

DCS inhibits EcDdlB phosphatase activity

Under the conditions of the PIX experiment, hydrolysis of ATP was detected as a side reaction over an incubation period longer than 8 h. The phosphatase activity of EcDdlB has been quantified by NMR under the conditions employed for the PIX experiment (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, kinetic measurements were performed using a coupled enzyme system (Fig. 2f). Fitting of the initial velocity data from the latter experiment to Eq. (2) provided a K m for ATP hydrolysis of 167 ± 13 µM and a V max of 0.29 ± 0.01 min−1.

where v is the velocity at substrate concentration A, V max is the maximal velocity, and K m is the Michaelis constant. Initial velocity data obtained in the presence of DCS show inhibition of ATP hydrolysis, and were fitted to Eq. (3) (IC50 11.5 ± 0.7 µM), confirming that the observed activity is specific to EcDdlB and not caused by the presence of an adventitious phosphatase contaminant (Fig. 2g).

where, I is the concentration of DCS, IC50 is the concentration of DCS necessary to give 50% inhibition, and n H is the Hill number. Together, these experiments demonstrate a direct interaction of DCS with ATP and positional isotope exchange of ATP γ-P, induced by DCS, consistent with the formation of DCSP.

The NMDA receptor’s glycine site cannot accommodate DCSP

In relation to neurotoxic effects associated with the binding of D-cycloserine to the NMDA receptor, it has been documented that D-serine, D-cycloserine and glycine bind to the NR1 region of the NMDA receptor in overlapping positions13. In order to explore the possibility that the phosphorylated D-cycloserine species may also bind within the NMDA receptor, we applied the docking algorithm eHiTS14 to the D-cycloserine binding region within the NR1 crystal structure, and modeled the resulting best docking “pose” (Supplementary Fig. 6a–d). These studies indicated that there is insufficient space in the NDMA ligand binding site to accommodate the DCSP species (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Using the scoring function in the de novo ligand design program SPROUT15, the predicted binding affinity for the phosphorylated D-cycloserine to NR1 is around two orders of magnitude lower than that predicted for the binding of D-cycloserine itself to NR1. Importantly, the phosphate group cannot be accommodated within the ligand binding site due to predicted steric clashes of DCSP with the wall of the NMDA ligand-binding cavity (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d).

Discussion

DCSP is clearly stable under conditions employed to crystallize and diffract EcDdlB but previous work indicated that alanyl-phosphates and related compounds are likely to break down rapidly in aqueous solution, precluding their experimental isolation for confirmatory purposes16. The highly reactive nature of acyl phosphates, and in particular, the great difficulties in terms of isolating and characterizing them, has been well established. Although very early chemical approaches have shown that insoluble silver salts of acetyl phosphate itself can be isolated17 all other reports involving these systems indicate that they are reactive and subject to ready decomposition. For example, under neutral conditions (pH = 7.2), it has been shown that acyl phosphates are rapidly hydrolyzed18 (e.g., rate of hydrolysis of acetyl phosphate at 39 °C and pH 7.2 = 4.4 × 103 min−1). More recent studies19 report that acyl-phosphorylated amino acids (e.g., that derived from valine), generated in aqueous solution, can be detected using NMR, but are somewhat transient, and undergo steady decomposition (rate = 5.7 × 10−4 s−1, corresponding to a halving of the concentration of the acyl phosphate intermediate after 30 min). These authors briefly investigated the mechanism of decomposition of the acyl phosphates and report that addition of methanol to the aqueous solution followed by evaporation of the solvents allowed the identification of methanol cleavage products (methyl phosphate) corresponding to attack of the phosphate group in the intermediate amino acid acyl phosphate by methanol.

PIX is the method of choice for mechanistic investigation of enzymatic reactions involving phosphate transfer from reactant to product or phosphate exchange between them at equilibrium20. The method exploits 31P NMR to monitor shift of the 31P resonance by substitution of bonded 16O with 18O and has been widely applied to clarify mechanisms of enzymatic reactions, including the demonstration of formation of the intermediate D-alanyl phosphate (also not stable in aqueous medium), during peptide bond formation catalyzed by Enterococcal VanA16 and Salmonella DdlA21 (Supplementary Fig. 2). It should be noted that in the case of the experiment with EcDdlB, ATP and DCS the PIX rate is of the order of 0.36 h−1, which is significantly slower than the rate obtained with VanA, about < 1 min−1 16. We believe this difference can be attributed to the intrinsic reactivity of the substrate (D-Ala) vs. the inhibitor (DCS).

The phosphatase activity of EcDdlB detected as a side-reaction alongside the PIX reaction was proved to be inhibited by DCS. The IC50 obtained for DCS-inhibition of ATPase activity (11.5 µM) is well in the range of K i values obtained for DCS-inhibition of E.coli Ddls biosynthetic reaction (9 µM for DdlA and 27 µM for DdlB)22. Interestingly, a value of 1.5 for the Hill number seems to suggest the existence of positive cooperativity for DCS inhibition of ATP hydrolysis reaction.

We conclude that it is highly unlikely that DCSP or analogs developed from this structure, if able to cross the blood-brain barrier, would result in NMDA receptor activation and the side effects associated with DCS treatment. Furthermore, in the high-level vancomycin resistance mechanism found in Enterococci, chromosomally encoded Ddl enzymes are superseded in function by transposon-borne D-alanine:D-lactate ligases (e.g., VanA, VanB) that enable the formation of peptidoglycan peptide termini that have low affinity to glycopeptide antibiotics9,23. If such DCSP-based inhibitors also bind to the D-alanyl-D-lactate ligases (e.g., VanA, VanB) then this would lead to renewed therapeutic utility of glycopeptide antibiotics in life threatening glycopeptide resistant infections.

In summary, the structural and biochemical analysis of EcDdlB in complex with DCSP represents both the first of a Ddl enzyme in complex with a D-alanyl-phosphate mimic and the only structure of a Ddl enzyme from any organism in complex with a clinically used antibiotic. Furthermore, our structural studies have suggested a novel mode of action for DCS, involving its phosphorylation to yield DCSP, which is to the best of our knowledge a previously undescribed chemical entity. The results underscore the biochemical flexibility of this remarkably simple antibiotic. This mechanistic diversity of antibiotic action is unusual amongst the natural antibiotics.

Methods

Protein purification and crystallization

Recombinant EcDdlB with an amino-terminal histidine-tag was expressed and purified from E. coli BL21(λDE3)Star-pRosetta, crystallized and cryoprotected for data collection as previously reported24. Briefly, after cells harvesting, resuspension in buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), lysis by sonication and centrifugation, EcDdlB was purified from the supernatant by Ni-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography.

Crystals were obtained by co-crystallization at 291 K using the hanging-drop method and a 2 µl drop containing one to one ratio of protein and crystallization solution (200 mM MgCl2, 25% PEG 3350, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0). Protein concentration was 12 mg ml−1 in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM EDTA buffer, containing 5 mM ATP or 5 mM ADP and 50 mM D-alanyl-D-alanine, and 5 mM ATP and 5 mM DCS. Crystals were flash cooled in liquid nitrogen using reservoir solution containing 30% glycerol as a cryoprotectant and used for X-ray diffraction data collection on beamline IO4 at the Diamond Light Source, U.K.

All crystals belonged to the orthorhombic space group P212121, with two molecules in the crystallographic asymmetric unit24. Following structure solution by molecular replacement, refinement of each structure was carried out by alternate cycles of REFMAC25 using non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) restraints and manual rebuilding in O26. Water molecules were added to the atomic model automatically by Arp/wARP27 and in the last steps of refinement all the NCS restraints were released. A summary of the data collection and refinement statistics is given in Table 1. For each structure, all 306 amino acid residues of the native protein, along with an extra 8 residues from the N-terminal His6 affinity tag sequence, are visible in molecule 1 of the asymmetric unit and the electron density is of a high quality throughout this molecule (Supplementary Fig. 1). Residues 3–306 could be fitted in molecule 2, but both the N- and C-terminal domains display higher flexibility in this molecule, as evidenced by less well-defined electron density. Nevertheless, the bound ligands are clearly defined in both subunits and refine well.

Structure description

Two of the EcDdlB structures solved in this study contained the dipeptide product D-Ala-D-Ala, but differ in the presence of either ADP or ATP. In both these structures, the dipeptide product makes essentially identical interactions with the enzyme. The protonated28 α-amino group of the N-terminal D-Ala (D-Ala1) makes a salt bridge with the carboxylate group of Glu-15, as in the original structure, to form the high affinity alanine binding site seen in EcDdlB and other related ligases9,29. The carbonyl oxygen of the peptide bond makes two hydrogen bonds, with the backbone amide NH of Gly-276 and the side chain of Arg-255 in the oxyanion pocket of the ligase. The C-terminal D-Ala of the product (D-Ala2) is bound with its carboxylate occupying the low affinity alanine binding site centered on side chain hydroxyl of Ser-281 and ε-amino group of Lys-281. The side chain hydroxyl of Tyr-216 also interacts with the product at the backbone NH of D-Ala2, corresponding to its amino end. The adenine ring of the ATP or ADP ligand lies in a pocket mainly composed of hydrophobic and aromatic residues, while the α- and β-phosphate groups are hydrogen bonded to the ε-amino groups of Lys-97, Lys-144, and Lys-215. In the ATP-containing structure, there are further links from the γ-phosphate to Lys-215, Arg-255 and the backbone amide nitrogen of Ser-150 (Fig. 1a). In the ADP-D-ALa-D-Ala structure, we find density for a putative carbonate ion at the equivalent spatial position the γ-phosphate group of ATP would occupy. We initially considered whether this density could correspond to an yttrium ion from the yttrium chloride used in crystallization, but density clearly represents a planar molecular species, not consistent with a metal ion. This was included in the model, and refined, and found to make interactions identical to those made by the γ-phosphate of ATP. The active site interactions observed in the DdlB:ADP:D-Ala-D-Ala structure parallel those observed in the two previous EcDdlB structures with ligands, which essentially mimic the transition state of the EcDdlB reaction (Fig. 1b).

Kinetic measurements

All chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, UK) or Sigma (Poole, UK). [γ-18O4]-ATP (>94% isotopic enrichment and 97% chemical purity) was purchased from Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories.

31P NMR experiments

31P NMR spectra were acquired at 25 °C using a Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer equipped with a 5mm quadruple-resonance PFG cryoprobe and operating at a 31P frequency of 283.4 MHz.

PIX reaction

Reaction mixture for PIX contained 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM [γ-18O4]-ATP, 6 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DCS. The PIX reaction was started by EcDdlB enzyme addition at 24.5 µM and the sample incubated at 25 °C. At time points equal to 15 s, 15 and 30 min, and 1, 2, 3.5, 5.5, 7.75, 18, and 24 h, aliquots of 500 µl were removed and quenched by addition of 50 µl of 0.5 M EDTA (Fig. 2e). Time points for the control experiment (Supplementary Fig. 3b) were taken at 15 s, 30 min, 1.5, 3.5, 6, and 20 h. After collection of the aliquot at 20 h, further 2 mM of fresh [γ-18O4]-ATP was added to the reaction mix and time points were taken at 15 s, 30 min, 1.5, 3.5, 6, and 20 h after addition. The final volume of the NMR sample was 600 µl containing 8% D2O added after quenching the reaction. A control experiment for detection of ATP hydrolysis under identical conditions of the PIX experiment was run on unlabeled ATP.

Phosphatase activity and inhibition assays

Initial velocities of the EcDdlB phosphatase activity were monitored continuously at 25 °C by UV–Vis spectrophotometry (Shimadzu UV-2550, Milton Keynes, UK) using a 1 cm path-length cell and coupling ATP hydrolysis to NADH oxidation (ε340 = 6220 M−1 cm−1) via a pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase system. Reaction mixtures contained 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 80 mM KCl, 0.10 mM NADH, 1.5 mM PEP, 1 µl ml−1 pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase enzyme solution (PK/LDH; stock solution of 6–10 U ml−1 PK and 9–14 U/ml−1 LDH) and variable ATP concentration (12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 750, 1000, 2000 µM). When included in the experiments, DCS was present at 1 mM (Fig. 2f). EcDdlB was at a final concentration of 14.4 µM. In the phosphatase inhibition assay (Fig. 2g) DCS concentration was 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 25, 30, 75, 150, 250 µM, whereas ATP concentration was 2 mM.

Data availability

The atomic coordinates and the structure factors for E. coli EcDdlB in complex with DCSP and D-ala-D-ala peptides have been deposited with the accession codes 4C5A, 4C5B and 4C5C. Other data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Payne, D. J., Gwynn, M. N., Holmes, D. J. & Pompliano, D. L. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 29–40 (2007).

Tommasi, R., Brown, D. G., Walkup, G. K., Manchester, J. I. & Miller, A. A. ESKAPEing the labyrinth of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 529–542 (2015).

East, S. P. & Silver, L. L. Multitarget ligands in antibacterial research: progress and opportunities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 8, 143–156 (2013).

Walsh, C. T. & Wencewicz, T. A. Prospects for new antibiotics: a molecule-centered perspective. J. Antibiot. 67, 7–22 (2014).

Neuhaus, F. C. & Lynch, J. L. The enzymatic synthesis of D-alanyl-D-alanine. 3. On the inhibition of D-alanyl-D-alanine synthetase by the antibiotic D-cycloserine. Biochemistry 3, 471–480 (1964).

Lambert, M. P. & Neuhaus, F. C. Mechanism of D-cycloserine action: alanine racemase from Escherichia coli W. J. Bacteriol. 110, 978–987 (1972).

Prosser, G. A. & de Carvalho, L. P. Metabolomics reveal D-alanine:D-alanine ligase as the target of D-cycloserine. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 4, 1233–1237 (2013).

Fujihira, T., Kanematsu, S., Umino, A., Yamamoto, N. & Nishikawa, T. Selective increase in the extracellular D-serine contents by D-cycloserine in the rat medial frontal cortex. Neurochem. Int. 51, 233–236 (2007).

Healy, V. L., Lessard, I. A., Roper, D. I., Knox, J. R. & Walsh, C. T. Vancomycin resistance in enterococci: reprogramming of the D-ala-D-Ala ligases in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 7, R109–R119 (2000).

D’Costa, V. M. et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477, 457–461 (2011).

Midelfort, C. F. & Rose, I. A. A stereochemical method for detection of ATP terminal phosphate transfer in enzymatic reactions. Glutamine synthetase. J.Biol. Chem. 251, 5881–5887 (1976).

Mullins, L. S. & Raushel, F. M. Positional isotope exchange as probe of enzyme action. Methods Enzymol. 249, 398–425 (1995).

Furukawa, H. & Gouaux, E. Mechanisms of activation, inhibition and specificity: crystal structures of the NMDA receptor NR1 ligand-binding core. EMBO J. 22, 2873–2885 (2003).

Zsoldos, Z., Reid, D., Simon, A., Sadjad, S. B. & Johnson, A. P. eHiTS: a new fast, exhaustive flexible ligand docking system. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 26, 198–212 (2007).

Simmons, K. J., Chopra, I. & Fishwick, C. W. Structure-based discovery of antibacterial drugs. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 501–510 (2010).

Healy, V. L. et al. D-Ala-D-X ligases: evaluation of D-alanyl phosphate intermediate by MIX, PIX and rapid quench studies. Chem. Biol. 7, 505–514 (2000).

Bentley, R. A new synthesis of acetyl dihydrogen phosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 70, 2183–2185 (1948).

Di Sabato, G. & Jencks, W. P. Mechanism and catalysis of reactions of acyl phosphates. II. Hydrolysis1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83, 4400–4405 (1961).

Biron, J.-P. & Pascal, R. Amino Acid N-carboxyanhydrides: activated peptide monomers behaving as phosphate-activating agents in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9198–9199 (2004).

Cohn, M. & Hu, A. Isotopic (18O) shift in 31P nuclear magnetic resonance applied to a study of enzyme-catalyzed phosphate–phosphate exchange and phosphate (oxygen)–water exchange reactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 200–203 (1978).

Mullins, L. S., Zawadzke, L. E., Walsh, C. T. & Raushel, F. M. Kinetic evidence for the formation of D-alanyl phosphate in the mechanism of D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 8993–8998 (1990).

Noda, M. et al. Self-protection mechanism in D-cycloserine-producing Streptomyces lavendulae. Gene cloning, characterization, and kinetics of its alanine racemase and D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase, which are target enzymes of D-cycloserine. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 46143–46152 (2004).

Roper, D. I., Huyton, T., Vagin, A. & Dodson, G. The molecular basis of vancomycin resistance in clinically relevant Enterococci: crystal structure of D-alanyl-D-lactate ligase (VanA). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8921–8925 (2000).

Batson, S., Rea, D., Fülöp, V. & Roper, D. I. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of a D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase (EcDdlB) from Escherichia coli. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66, 405–408 (2010).

Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 (1997).

Jones, T. A., Zou, J. Y., Cowan, S. W. & Kjeldgaard, M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119 (1991).

Perrakis, A., Morris, R. & Lamzin, V. S. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 (1999).

Fan, C., Park, I. S., Walsh, C. T. & Knox, J. R. D-alanine:D-alanine ligase: phosphonate and phosphinate intermediates with wild type and the Y216F mutant. Biochemistry 36, 2531–2538 (1997).

Fan, C., Moews, P. C., Walsh, C. T. & Knox, J. R. Vancomycin resistance: structure of D-alanine:D-alanine ligase at 2.3 A resolution. Science 266, 439–443 (1994).

Cruickshank, D. W. Remarks about protein structure precision. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 583–601 (1999).

Brunger, A. T. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature 355, 472–475 (1992).

Acknowledgements

Crystallographic data were collected at beamline IO4 at Diamond Light Source, U.K., and we acknowledge the support of Dr Ralf Flaig. This work was supported by a University of Warwick PhD studentship to SB and in part by MRC research grants G500643, G0701400, G1100127, Wellcome Trust equipment grants 071998, 068598; the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (FC001060), the UK Medical Research Council (FC001060), and the Wellcome Trust (FC001060); the Slovenian Research Agency (Grant No. L1-6745 to S.G.); and a UNESCO–L’Oréal International Fellowship “For Women in Science” to V.M. Equipment used in this research was obtained, through the Birmingham-Warwick Science City Translational Medicine: Experimental Medicine Network of Excellence project, with support from Advantage West Midlands (AWM). We thank the MRC Biomedical NMR Centre (The Francis Crick Institute, London) for the use of spectrometers and Dr Geoff Kelly for advice on NMR data collection. We thank Dr Karen Hinxman for help with data deposition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., C.d.C., V.M., D.R., C.T., and K.J.S. performed all the experimental procedures. S.G., A.J.L., C.G.D., V.F., and C.W.G.F. supervised biochemical, crystallographic, and modeling experiments respectively, L.P.S.d.C., A.J.L., and D.I.R. wrote the paper and directed the overall research programme.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Batson, S., de Chiara, C., Majce, V. et al. Inhibition of D-Ala:D-Ala ligase through a phosphorylated form of the antibiotic D-cycloserine. Nat Commun 8, 1939 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02118-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02118-7

This article is cited by

-

Mur ligase F as a new target for the flavonoids quercitrin, myricetin, and (–)-epicatechin

Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design (2023)

-

The Struggle to End a Millennia-Long Pandemic: Novel Candidate and Repurposed Drugs for the Treatment of Tuberculosis

Drugs (2022)

-

Molecular mechanism underlying substrate recognition of the peptide macrocyclase PsnB

Nature Chemical Biology (2021)

-

d-Cycloserine destruction by alanine racemase and the limit of irreversible inhibition

Nature Chemical Biology (2020)

-

Mechanisms of action of ionic liquids on living cells: the state of the art

Biophysical Reviews (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.