Abstract

Objective

To examine associations between different types of sweet drinks consumed in early life and adult adiposity.

Design

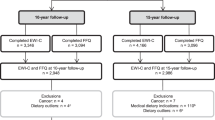

The analysis involved the secondary analysis of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children which followed children from birth to 24 years. Adiposity was measured using Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry while food frequency questionnaires and diaries monitored diet. ‘Early exposure’ to sweet drinks was defined as giving a sugar-sweetened beverage or 100% fruit juice (FJ), before two years of age.

Results

Early exposure to cola was associated with higher fat mass, android fat mass and BMI at age 24 years; whereas early exposure to apple juice was associated with lower adult adiposity in females but not males. When age three, exposure to cola was associated with a greater intake of energy, carbohydrates, protein, fat, and less fruit and more fried foods. In contrast, early exposure to apple juice was associated with higher protein and lower fat intakes and consuming more fruits/vegetables and less fried foods. Parental education, adiposity and socio-economic status influenced whether SSB or FJ was given to a child.

Conclusions

Early drinking of sugar sweetened beverages was associated with a less healthy dietary pattern, and greater adult adiposity. Early drinking of apple juice was associated with a healthier dietary pattern, and lower fat mass in adult females. The choice of drink was associated with social deprivation. As the dietary causes of adult obesity begin in early childhood, increased attention should be given to diet in the first years of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are many reports that consuming sugar sweetened drinks (SSB) in childhood is associated with a greater risk of obesity, and some studies have treated all sweet drinks as similar; for example combining carbonated drinks, sweetened tea, energy drinks, fruit-based drinks, and 100% fruit juice with no added sugar (FJ) [1]. Others have attempted to differentiate between SSB and drinks such as FJ that contain endogenous sugar, often reporting a lack of association between FJ and body weight [2,3,4,5]. There are, however, reviews that come to the opposite conclusion. Based on eight prospective cohorts, Hebden [6] found that drinking fruit juice increased body weight, although seven of the eight studies involved simply asking how frequently ‘fruit juices’ were consumed, without distinguishing 100% juices from those to which sugar had been added. The question therefore considered, is whether we should differentiate between SSB, FJ, and juice-containing drinks with added sugar, when considering how beverages in childhood influence longer-term weight.

It is, however, acknowledged that those consuming one food, will be more likely to choose other foods, forming a dietary pattern [7,8,9]. The Standard American or Western pattern diet is characterized by a high intake of refined and processed foods, that is high in both fat and sugar. Importantly those who eat this diet are more likely to choose SSB [10]. As such, SSB may be a marker for the choice of a highly calorific diet, so that changing what is drunk will have a limited impact on energy intake.

The present interest in the diet during childhood reflects that early diet is a risk factor for adult obesity, and the influence of SSB has been less studied in the young. Are SSB gateway foods that encourage the consumption of sweetened foods in later life, or a marker for a later obesity-inducing dietary pattern? If so, should attention be directed to a dietary pattern, rather than a single nutrient or source of that nutrient?

The study therefore considered whether all sugar drinks should be treated as a single category, or alternatively whether the influence of each should be examined separately. Secondly it was considered whether the impact of a sweet drink should be viewed as part of a dietary pattern. Thirdly whether males and females respond differently when the choice of drink was examined.

Methods

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children study (ALSPAC)

The sample comprised women recruited in the Bristol area of the United Kingdom, who gave birth between 1st April 1991 and 31st December 1992 [11, 12] and included 14,541 pregnancies that resulted in 13,988 children alive at one year.

Height, weight and adiposity

Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (Holtain Ltd, Crymych Pembrokeshire, UK), and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg using Tanita scales (Wardworth Ltd, Bolton, UK). Halfway between the lower ribs and the pelvic bone, a tape was used to measure waist circumference to the nearest 1 mm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in metres squared.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA scan)

A Lunar Prodigy narrow fan-beam densitometer (GE Healthcare, Bedford, UK) was used for whole-body scanning. Android fat mass measures abdominal fat around the organs and in this respect differs from subcutaneous fat. Total fat mass at 24 years was used as the dependent variable.

Diet

When the children were two years of age, the carer was asked if between 15 months and 2 years the child drank cola, other fizzy drinks, apple juice, other fruit juices or fruit squash (a drink containing some fruit juice to which sugar was added), eliciting a yes/no response, although the amount consumed was not recorded. For the purposes of the present analysis, ‘early exposure’ was defined as any consumption of the above drinks before 2 years of age.

The child’s diet at age 3 years was assessed using a Food Frequency Questionnaire completed by the mother or partner. From the foods available, to gain a general impression of the dietary style, various foods were examined as falling into the following groups. The choice of food items was based on an analysis of dietary patterns in this cohort that establish a processed food and healthy pattern of consumption [13].

-

1.

Fatty foods: Burger and sausages; French fries; Fried food.

-

2.

Sweet tasting foods: Chocolate; Sweets; Biscuits; Cakes; Puddings.

-

3.

Fruit and vegetables: Fresh fruit; Green vegetables; Root vegetables; Salad.

-

4.

Other foods; Fish; Meat; Pizza.

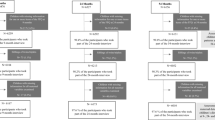

Each food item was rated as having been eaten ‘never/rarely,’ ‘once in 2 weeks,’ ‘1–3 times/week,’ ‘4–7 times/week,’ or ‘more than once a day.’ These responses were modified to reflect weekly consumption: never/rarely was given a score of zero; once in two weeks scored 0.5; 1–3 a week scored 2; 4–7 a week scored 5.5; more than once a day scored 10.

Subsequently parents completed a three-day dietary diary (one weekend day and two weekdays), when the child was 4 and 7 years of age. At 11 and 13 years of age the child kept a similar record. The records were checked with the parents or children, and were used to calculate the daily mean intakes [14] using the McCance and Widdowson’s Food Tables [15]. Free sugars reflected any monosaccharides or disaccharides that had been added to foods, plus sugars occurring naturally in honey, syrups, and fruit juices. Misreporting of dietary data was assessed at age 11 and 13-years using estimates of energy requirement based on age, sex and body weight, and the ratio between the reported intake and estimated need [16].

Demographics and confounding variables

Partner’s education

The highest qualification achieved was classified as Certificate of Secondary Education/Vocational Education; O-levels; A-levels; Degree (higher scores were given for longer education).

Mother’s and partner’s occupational status

Social class was classified as 1) Professional jobs, 2) Managerial and technical, 3) Skilled non-manual, 4) Skilled manual, 5) Partly skilled, 6) Unskilled (lower scores given for higher status).

Index of multiple deprivation

Various domains were combined to create a single dimension incorporating income; employment; health deprivation and disability; education, skills and training; housing [17].

Data were also collected on partner’s BMI, age of mother at the child’s birth, and the mother’s prenatal weight.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools (Research Electronic Data Capture) [18]. Regression equations were produced using the General Linear Model, with drinks added as dummy variables to examine the effect of drink on adiposity (SPSS version 28.0.1, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). However, as males differ in adiposity from females, and the response to the drinks differed, each gender was studied separately. Hierarchical regression equations were used to consider the influence of factors other than drink, with the type of drink added to create a second model. Collinearity was examined, using the variance inflation factor, to remove variables that were highly correlated. On all occasions two-sided tests were used and to deal with the problem of multiple comparisons, attention was paid to a probability less than 0.01, although lesser significances are reported.

Results

Data for the five types of sweet drink are found in supplementary information but, for brevity and clarity, the focus of this paper is on early exposure to cola, apple juice or fruit squash, as the other two drinks had little influence (see Supplementary Material). The choice of apple juice reflected that it was the predominant juice offered to children in the 1990s.

Table 1 reports associations between sweet drinks and adult adiposity. In males, adiposity was greater only after drinking cola (Table 1), with the exception that not drinking apple juice was associated with a higher BMI. In contrast, with females, greater adiposity was associated with drinking fruit squash and not drinking 100% fruit juice.

A question is whether these associations were related exclusively to sweet drinks, rather than a dietary pattern. At three years of age, cola, fruit squash (Table 2) or fizzy drinks (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4) were associated with consuming more energy, carbohydrate, fat, protein, and non-milk extrinsic (NME) sugars, but less non-starch polysaccharides (NSP). In contrast, apple juice was associated with a lower intake of fat and NME sugars but more protein and NSP.

As SSB contain neither protein nor fat, the rest of the diet must differ. Giving boys cola, fruit-squash (Table 3) or fizzy drinks (Supplementary Table S5), was associated with eating more burgers and sausages, pizza, French fries, meat, chocolate, and sweets, but less fruit. In contrast, drinking apple juice was associated with lower intakes of burgers and sausages, chocolate, sweets, puddings, or biscuits, but a higher intake of fish, fruit, green vegetables, and salad. The pattern with girls was similar.

Supplementary material reports the association between the drinks consumed prior to two years of age, and later diet (Supplementary Table S6). In boys, cola consumption before two years was associated with a higher energy intake between four and nine years of age. After apple juice, girls when four years of age, consumed less energy.

Food choice and drinks

To consider the influence of the overall diet on adult adiposity, a first model of a hierarchical regression was developed based on the fourteen food items listed in the methods section. Then a second model was created by adding early exposure to sweet drinks.

In males, diet predicted body fat when 24 years (adjusted R2 = 0.026, F (19, 1109) = 2.598, p < 0.001), with French fries, burgers/sausages and root vegetables when three years, having a significant influence (Table 4). All five drinks were removed from the equation because of collinearity.

With females the equation was also significant (adjusted R2 = 0.020) F (19,1749) = 2.789, p < 0.001), with eating burgers/sausages and French fries being associated with greater adiposity, although those who did not eat biscuits and fresh fruit had a greater fat mass (Table 4). Not eating biscuits was possibly a reaction to a greater level of adiposity.

Demographic variables

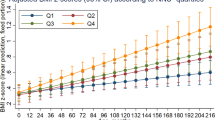

Although energy consumption is often related to long-term body weight, it is possible that dietary patterns are markers for demographic variables that independently predispose to adiposity. The percentage of parents giving either cola or apple juice changed as the geographical area where the family lived became progressively more deprived (Fig. 1; Chi squared p < 0.001). The greater was social deprivation, the more likely it was that cola had been drunk, whereas it was less likely that apple juice had been given to child.

The population was divided into quintiles based on the Multiple Index of Deprivation. The percentage of children in each of these five categories, that were given either cola or apple juice, are reported. The numbers given these drinks differed depending on the degree of deprivation (Chi Square p < 0.001).

Supplementary material (Supplementary Table S7) lists variables associated with the provision of drinks. Cola was more likely to be given if parents were less educated, had a lower status job, the mother was younger, or either parent had a higher body weight. The early provision of apple juice was associated with an opposite pattern. These variables were included in the first model of a hierarchical regression with the five drinks subsequently then added as a second modle. Table 5 reports the significant influences in the second model. In males the BMI of the partner, the pre-birth weight of the mother and deprivation, positively influenced adiposity at 24 years. Although drinking apple juice was associated with lower adiposity, all five drinks were removed from the equation because of collinearity. Similarly, both the BMI of the partner and weight of the mother predicted the adiposity of females, but again all five drinks were removed from the equation for reasons of collinearity.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that the sweet drink given to children before two years of age was associated with adiposity at 24 years of age (Table 1). To our knowledge, this is the longest period over which such an association has been reported. There was, however, evidence that the consequences of the choice of drink relied on more than the drink itself.

In males, early exposure to cola, fruit squash (Table 2), or fizzy drinks (Supplementary Table S3), were at three years associated with a diet containing more energy, carbohydrates, fat, protein, and NME sugars, but less NSP. In contrast, early exposure to apple juice was not associated with energy intake at age three years, but there was a higher consumption of protein and NSP, and a lower consumption of fat and NME sugars. The pattern in females was similar. The choice of drink was only a part of a wider dietary pattern. Thus sugar in drinks should not be considered in isolation, as they may be associated with a healthy or less healthy diet (Tables 2 and 3). Another consideration is that FJ contains significant levels of vitamin C, folate, potassium, carotenoids, and flavonoids which are health promoting [19, 20].

The finding that dietary patterns are important was consistent with Northstone and Emmett [13], who found when diets at three, four, seven and nine years of age were compared, dietary patterns persisted over time. A ‘processed’ diet included the eating of chocolate, sweets and crisps and high fat, high sugar processed foods, but also the drinking of fizzy drinks. In contrast, fruit, vegetables, salads, pasta. and rice were part of a ‘health conscious’ diet that included fruit juice. Similarly in the present study, cola, other fizzy drinks, and fruit squash were associated with consuming burgers/sausages. pizza, fried foods, French fries, meat, chocolate, and sweets (Table 3, Supplementary Table S5). The pattern with apple juice was broadly opposite to SSB; it was less likely that burgers/sausages, fried food, and French fries were eaten (Table 3), although more fish, vegetables, and fruit were consumed.

These findings question an approach that concentrates on sugar per se, rather than a diet that happens to contain sources of sugar. Cola and apple juice both provide about 9–10 g of sugar per 100 ml, but in males cola was associated with greater adult adiposity, whereas apple juice was not (Table 1). In females, cola was also associated with higher adiposity, whereas apple juice was associated with lower adiposity (Table 1).

Such observations should not be a surprise as SSB consumption has been associated with greater adiposity when FJ consumption was not [5]. When FJ has been associated with higher body weight, 100% FJ has not been distinguished from exogenously sweetened juice [6]. The importance of this observation is illustrated by the present study, when fruit squash was found to be similar to SSB rather than FJ, in terms of macronutrient intake at three years (Supplementary Tables S4 and S6); dietary patterns at three years (Supplementary Table S5); mother’s weight and educational level; mother’s age at the child’s birth; partners BMI (Supplementary Table S7) and in females the BMI and total fat mass (Supplementary Table S2).

A reason to study early nutrition is that body fat increases after birth, and then declines only to subsequently increase from three to seven years. An earlier adiposity rebound has been associated with a greater risk of adult obesity [21, 22], such that if it occurs about three years of age rather than later, there is a greater risk of adult obesity [23], a phenomenon that occurs more often in girls [24, 25]. The question arises as whether the present findings were influenced by the age the drinks were given, as metabolic programming at critical stages in development predisposes to obesity throughout life [26]. If so, an insight into the influence of early feeding may prevent later weight gain, but attention needs to be directed to feeding in the first years of life, rather than the later ages that have often been studied in nutritional interventions.

However, the influence of diet needs to be placed in context, as although with a large sample size statistical significance was obtained, the regression equations accounted for a small amount of variance. In contrast, demographic variables had a far greater influence than the choice of drink given to the child (Table 5). Similarly, it has been reported that a child’s pattern of dietary intake is strongly influenced by socioeconomic characteristics. Factors such as a younger maternal age, and the early introduction of complementary feeding, are associated with an unhealthy dietary style [27]. Although nutritionists naturally emphasize diet, it should be assumed that a correlation between diet and adiposity reflects more than the calories provided, as the effects of demographic variables associated with diet (Table 5) had a greater influence than diet per se. A consideration of demographic variables will indicate to whom nutritional attention should be directed, and when.

A positive is that the findings add to the evidence that diet during early childhood is associated with risk of obesity in later life. As such, the attention of nutritionists should be directed to the early diet of young children, and the impact of a nutritional intervention at a younger rather than later age. There needs to be a greater emphasis on controlling energy intake in infancy and young childhood.

Data availability

ALSPAC is a longitudinal birth cohort study that began in 1991 and continues to this day. The study encourages the use of its data and will provide access to all ‘bona fide’ researchers. Those interested should approach ALSPAC at the University of Bristol, England. Their access policy is described on their website (ALSPAC_Access_Policy.pdf (bristol.ac.uk)).

References

Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:274–88.

O’Neil CE, Nicklas TA. A Review of the Relationship Between 100% Fruit Juice Consumption and Weight in Children and Adolescents. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2008;2:315–54.

Frantsve-Hawley J, Bader JD, Welsh JA, Wright JT. A systematic review of the association between consumption of sugar-containing beverages and excess weight gain among children under age 12. J Pub Health Dent. 2017;77:S43–S66.

Pereira A, Fulgoni V. Consumption of 100% fruit juice and risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:625–29.

Sakaki JR, Rodriguez NR, Fernandez M-L, Puglisi MJ, Chen M-H, Chun OK. Fruit juice and childhood obesity: a review of epidemiologic studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;28:1–15.

Hebden L, O’Leary F, Rangan A, Lie ES, Hirani V, Allman-Farinelli M. Fruit consumption and adiposity status in adults: a systematic review of current evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:2526–40.

Wang P, Song M, Eliassen AH, Wang M, Giovannucci EL. Dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer: a comparative analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2023;52:96–106.

Paradis AM, Godin G, Perusse L, Vohl MC. Associations between dietary patterns and obesity phenotypes. Int J Obes. 2009;33:1419–26.

English LK, Raghavan R, Obbagy JE, Callahan EH, Fultz A, Nevins JEH, et al. Dietary patterns and health: Insights form NESR systematics reviews to inform the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2024;56:75–87.

Yon BA, Johnson RK. Dietary Patterns and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among Adolescents and Adults. Curr Nutr Rep. 2014;3:43–50.

Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, et al. Cohort Profile: the ‘children of the 90s’-the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:111–27.

Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Boyd A, Golding J, Davey Smith G, et al. Cohort Profile: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:97–110.

Northstone K, Emmett PM. Are dietary patterns stable throughout early and mid-childhood? A birth cohort study. Brit J Nut. 2008;100:1069–76.

Emmett P, Rogers I, Symes C. Food and nutrient intakes of a population sample of 3-year-old children in the southwest of England in 1996. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:55–64.

McCance & Widdowson’s the Composition of Foods. 5th ed. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 1991.

Emmett PM, Jones LR. Diet, growth, and obesity development throughout childhood in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:175–206.

Elliott P, Cuzick J, English D, Stern R. Geographical and Environmental Epidemiology: Methods for Small-Area Studies. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997.

Harris IPA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez JN, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42:377–81.

Benton D, Young HA. Role of fruit juice in achieving the 5-a-day recommendation for fruit and vegetable intake. Nutr Rev. 2019;77:829–43.

Ruxton CHS, Derbyshire E, Sievenpiper JL. Pure 100% fruit juices - more than just a source of free sugars? A review of the evidence of their effect on risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity. Nutr Bull. 2021;46:415–31.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Bellisle F, Sempé M, Guilloud-Bataille M, Patois E. Adiposity rebound in children: a simple indicator for predicting obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39:129–35.

Rolland-Cachera MF, Deheeger M, Maillot M, Bellisle F. Early adiposity rebound: causes and consequences for obesity in children and adults. Int J Obes. 2006;4:S11-17.

Zhou J, Zhang F, Qim X, Li P, Teng Y, Zhang S, et al. Age at adiposity rebound and the relevance for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2022;46:1413.

Doi L, Williams AJ, Frank J. How has child growth around adiposity rebound altered in Scotland since 1990 and what are the risk factors for weight gain using the Growing Up in Scotland birth cohort 1?. BMC Pub Health. 2016;16:1081.

Johnson W, Li L, Kuh D. How has the age-related process of overweight or obesity development changed over time? Co-ordinated analyses of individual participant data from five United Kingdom birth cohorts. PLoS Med. 2016;12:e1001828.

Strain J, Spaans F, Serhan M, Davidge ST, Connor KL. Programming of weight and obesity across the life course by the maternal metabolic exposome: A systematic review. Mol Asp Med. 2022;87:100986.

Santos LP, Assuncao MCF, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Barros AJD. Dietary intake patterns of children aged 6 years and their association with socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, early feeding practices and body mass index. BMC Pub Heath. 2016;16:1055.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the facilities provided by Swansea University, and all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses.

Funding

The European Fruit Juice Association, Brussels, gave an “Unrestricted grant” to Swansea University that was used to pay for access to the ALSPAC data base. Legally such a gift cannot impose any restrictions on its use, therefore the decision to conduct this study, its planning, execution, and the decision to publish, were those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors established the question to be asked and approach to be taken. DB produced a first draft that was modified after critical input, evaluation, and discussion. Both authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DB has served on the scientific advisory board of the European Fruit Juice Association, although he was no longer a member when this study was carried out. HY has no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The present study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and Local National Health Services Research Ethics Committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. A fully searchable data dictionary provides details of the data (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benton, D., Young, H.A. Early exposure to sugar sweetened beverages or fruit juice differentially influences adult adiposity. Eur J Clin Nutr (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01430-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-024-01430-y