Abstract

Study design

Pilot study (case series).

Objective

The objective of this study was to establish spinal neurophysiological changes following high-frequency transspinal stimulation during robot-assisted step training in individuals with chronic motor complete spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting

University research laboratory (Klab4Recovery).

Methods

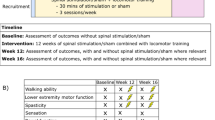

Four individuals with motor complete SCI received an average of 18 sessions of transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region with a pulse train at 333 Hz during robotic-assisted step training. Each session lasted ~1 h, with an average of 240 stimulations delivered during each training session. Before and after the combined intervention, we evaluated the amplitude modulation of the long-latency tibialis anterior (TA) flexion reflex and transspinal evoked potentials (TEP) recorded from flexors and extensors during assisted stepping, and the TEP recruitment curves at rest.

Results

The long-latency TA flexion reflex was depressed in all phases of the step cycle and the phase-dependent amplitude modulation of TEPs was altered during assisted stepping, while spinal motor output based on TEP recruitment curves was increased after the combined intervention.

Conclusion

This is the first study documenting noninvasive transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training depresses flexion reflex excitability and concomitantly increases motoneuron output over multiple spinal segments for both flexors and extensors in people with motor complete SCI. While both transspinal stimulation and locomotor training may act via similar activity-dependent neuroplasticity mechanisms, combined interventions for rehabilitation of neurological disorders has not been systematically assessed. Our current findings support locomotor training induced neuroplasticity may be augmented with transspinal stimulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modulation of spinal reflexes during stepping contributes to the control of coordinated locomotor muscle activity essential to walking [1, 2]. After spinal cord injury (SCI), coordination of reflexes and muscle activity are largely disrupted [3], resulting in impaired mobility and poor quality of life. Activity-based rehabilitation therapies, like manual- or robot-assisted locomotor training promote recovery after SCI. Locomotor training restores impaired walking function by improving stepping coordination and kinematics. These improvements are partly driven by functional reorganization of spinal circuits that restore phase-dependent modulation of spinal reflexes, like flexor and extensor muscle reflexes, and coordinated locomotor muscle activity during stepping [4, 5].

Similarly, noninvasive transcutaneous spinal cord (termed here as transspinal) stimulation supports motor recovery after SCI. For instance, transspinal stimulation reduces spasticity [6], improves functions of the autonomic nervous system [7,8,9,10], and restores voluntary locomotor activity and descending motor control [11,12,13]. Tonic transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region at moderate frequencies (5–40 Hz) generate locomotor-like muscle activity and movements in paralyzed or paretic muscles after SCI [11,12,13,14]. Transspinal stimulation may thus be used to augment the benefits of locomotor training. A recent modeling study suggested that high-frequency (e.g., >100 Hz) tonic spinal stimulation may provide a better alternative to modulating spinal networks and minimize potential harmful effects of occluding sensory feedback critical to motor recovery after SCI [15]. No study to date has examined whether high-frequency transspinal stimulation can potentiate locomotor training induced neuroplasticity.

Despite the realities of clinical practice, studies incorporating combined interventions are scarce. Locomotor training has been coupled with transcranial and transspinal direct current stimulation [16,17,18]. Improvements in walking speed and reduced spasticity were reported similar to that observed after one session of transspinal stimulation [16,17,18]. It is well established that after SCI, the short-latency tibialis anterior (TA) flexion reflex is abolished or barely present and a late, long-lasting TA flexion reflex appears [19, 20]. This, along with spontaneous firing of motoneurons at resting states [21], contribute to the muscle spasms experienced by individuals with SCI. Interventions targeting restoration of appropriate spinal reflex modulation and strengthening of motor output are thus in great need.

In this study, high-frequency transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region was delivered during robot-assisted step training over multiple sessions. Before and 1 day after the combined intervention, we determined the: (1) amplitude modulation of the long-latency TA flexion reflex and transspinal evoked potentials (TEPs) recorded from flexors and extensors of both legs during assisted stepping, and (2) spinal motor output based on TEP recruitment curves recorded from ankle flexor and extensor muscles.

Patients and methods

Patients

All procedures during the experiments and training were conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki after full Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval by the City University of New York IRB committee (IRB Number 2017-0261). A written informed consent was obtained from all participants before study enrollment.

Individuals with SCI were recruited based on the following criteria: age 18–65 years, more than 6 months after injury, and AIS A or B. Interested participants were excluded if they had concomitant traumatic brain injury, stroke or peripheral nerve injury, cognitive impairment, not medically stable, or had implanted pacemaker or baclofen pump that could malfunction during or after spinal stimulation.

Four male individuals (35.5 ± 8.9 years old) with chronic motor complete SCI ranging from C6 to T9 participated in the study. Participants were instructed to refrain from alcohol and caffeine consumption at least 24 h before and be cannabis-free for more than 2 weeks before testing.

Transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training

Transspinal stimulation over the thoracolumbar region was delivered based on our previously published procedures [22]. A single cathode electrode (Uni-PatchTM EP84169, 10.2′ 5.1 cm2, MA, USA) was placed longitudinally along the vertebrae equally between the left and right paravertebral sides covering T10 to L1–L2 vertebral levels. A pair of interconnected reusable self-adhesive anode electrodes (same type as the cathode), were placed on either side of the umbilicus or bilaterally on the iliac crests depending on the participant’s level of comfort during stimulation or if stimulation caused bladder discomfort. The cathode and anode electrodes were connected to a constant current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer, UK) that was triggered by Spike 2 (Cambridge Electronics Design Ltd., UK) or LabView (National Instruments, Austin TX) scripts. Optimal electrode placement was based on presence of TEPs in both knee and ankle muscles at low stimulation intensities, and presence of ankle TEP depression upon paired transspinal stimuli at an interstimulus interval of 100 ms [22]. Once the optimal stimulation site was identified, the electrodes were maintained via Tegaderm transparent film (3M Healthcare, St Paul, Minnesota, USA). To ensure consistency of stimulation site across training sessions, the skin area was marked by nontoxic skin pen and covered by Tegaderm film.

During training, transspinal stimulation was delivered at 333 Hz with a pulse train consisting of 12 pulses with a total 33 ms duration during the stance phase based on the foot switch signals. We used high-frequency transspinal stimulation at low intensities in order to have similar effects to the spatiotemporal stimulation patterns reported with epidural stimulation [15]. Stimulation intensities ranged from 0.8 to 1.2 times the right soleus (SOL) TEP resting threshold observed at baseline depending also on each participant’s reported comfort level. At baseline, the SOL TEP resting threshold intensity was 193 ± 87 mA across subjects.

Participants received an average of 18 sessions (range: 17–20) of transspinal stimulation delivered during body weight supported (BWS) step training with a robotic gait orthosis system (Lokomat 6 Pro®, Hocoma, Switzerland) 5 days/week for 1 h/day. The Lokomat BWS ranged from 50 to 76% (62 ± 10) and the treadmill average speed was 0.54 ± 0.35 m/s across subjects. All subjects before the intervention stepped with full Lokomat leg guidance force given their inability to maintain upright standing posture without knee buckling. After the intervention, the average BWS, treadmill speed and Lokomat leg guidance force were 25 to 79% (53 ± 18.5), 0.64 m/s ± 0.04, and 85%, respectively. Transspinal stimulation and robot-assisted step training were well tolerated by all participants, blood pressure remained stable during training sessions, and no adverse events were encountered during the combined intervention.

Neurophysiological assessments before and after transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training

EMG recordings

Surface EMG activity was recorded by single bipolar differential electrodes (Motion Lab Systems Inc., Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA) from the left and right SOL, medial gastrocnemius (MG), TA, medial hamstrings (MH), vastus lateralis (VL), vastus medialis (VM), gracilis (GRC), and peroneus longus (PL) muscles. EMG signals were amplified, filtered (10–1000 Hz), sampled at 2000 Hz via a 1401 plus (Cambridge Electronics Design Ltd., Cambridge, UK) when EMG data were collected at rest and via a National Instruments (Austin, TX) data board when EMG data were collected during stepping.

Neurophysiological tests to establish neuronal reorganization

The flexion reflex was evoked with a pulse train of 26.5 ms total duration at 333 Hz via a bipolar bar electrode placed along the right sural nerve using a constant current stimulator (DS7A, Digitimer Ltd., Hertfordshire, UK). The optimal stimulation site corresponded to the site where a response in the right TA muscle was present at the lowest stimulation intensity, while no activity was observed in triceps surae and toe extension that suggests excitation of plantar nerve axons and thus antagonistic toe extensors. When the stimulation site was identified, the bipolar bar electrode was replaced by two disposable pre-gelled circular electrodes (area 77 mm2, interelectrode distance of 3 cm; Suretrace RTL 1800C-003, Ag/AgCl, ConMed Corp., NY, USA) and maintained in place via prewrap. Then, each subject was fitted to the Lokomat upper body harness and leg braces and placed in standing at a BWS equivalent to that used during step training. The flexion reflex threshold during BWS standing with the right leg semi-flexed and unloaded was determined and was 82 ± 26 mA across subjects. During stepping, sural nerve stimulation was delivered at 1.3 multiples of the right TA flexion reflex threshold established during standing. TA flexion reflexes were triggered based on the foot switches placed on the ipsilateral foot, and were delivered randomly at different phases of the entire step cycle which was divided into 16 equal bins by LabVIEW customized software program [23,24,25].

Changes in motoneuron output were established based on the TEP recruitment input–output curves assembled with subjects supine (hip–knee at 30° flexion, legs in midline supported by bolsters). Single pulse transspinal stimulation was delivered at 0.2 Hz at increasing intensities from below resting motor threshold until a plateau in TEP responses was reached. TEPs were also recorded during BWS stepping following transspinal stimulation at 1.3 TA TEP threshold observed during standing, with similar methods to those we have previously used [25].

Stimuli were triggered every three to four steps, and responses were recorded randomly at each bin (n = 16) of the step cycle based on the right foot switch requiring ≥2000 steps to complete all stimulation paradigms. Bin 1 corresponded to heel contact. Bins 8, 9, and 16 corresponded approximately to stance-to-swing transition, swing phase initiation, and swing-to-stance transition, respectively. Stimulations were well tolerated by all participants, blood pressure remained stable throughout testing, and no adverse events were encountered during the recordings.

Data analysis

EMG signals during stepping (with and without stimulation) were full-wave rectified, high-pass filtered at 20 Hz and low-pass filtered at 500 Hz using a 4th order Butterworth filter. The TA flexion reflex at each bin of the step cycle was measured as the area under the full-wave rectified curve for a time window of 150 ms duration that started 130 ms from the beginning of the pulse train and termed here as long-latency flexion reflex [23, 24]. At each bin of the step cycle, the full-wave integrated area of the TA long-latency flexion reflex was calculated. For each subject, the average EMG of non-stimulated steps (control EMG) at identical time windows and bins was subtracted from the average EMG of stimulated steps (reflex EMG) to allow estimation of the net flexion reflex amplitude [23, 26, 27]. The average subtracted reflex EMG was then normalized to the maximum control EMG in order to group the reflex EMG across subjects. Statistical significance between the normalized flexion reflexes recorded before and after the combined intervention were established with a repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 16 times 3 levels. The first level corresponds to bins, and the second level corresponds to the treadmill speed (S1: speed at baseline used for recordings before or after training; S2: last training session speed used for recordings after training).

The background EMG activity of the right TA muscle at each bin was estimated from the mean value of the rectified and filtered EMG for a duration of 50 ms (high-pass filtered at 20 Hz, rectified, and low-pass filtered at 400 Hz), beginning 100 ms before sural stimulation. The mean amplitude of the long-latency TA flexion reflex recorded before and after the combined intervention was plotted against TA background activity (normalized to the maximum EMG), and a linear least-square regression was fitted to the data. This analysis was conducted separately for each subject and for the pool data.

TEPs recorded upon single pulse transspinal stimulation for TEP recruitment input–output curves from each muscle were measured separately as the area under the full-wave rectified waveform for identical time windows before and after training (Spike 2, CED Ltd., U.K.). These TEPs were normalized to the homonymous maximal TEP (TEPmax) recorded before training. The normalized TEPs were plotted against the non-normalized stimulation intensities and a Boltzmann sigmoid function (SigmaPlot 11, Systat Software Inc.) was fitted to the data to establish the predicted stimulation intensity corresponding to the stimulation intensity that evoked 50% of maximal TEP (S50). Then, TEPs recorded from each muscle were grouped based on normalized intensities across subjects. Similarly, TEPs recorded during stepping were measured as the area under the full-wave rectified waveform and were normalized to the homonymous maximal TEP. The mean amplitude of TEPs from each muscle recorded before and after training was plotted against the background EMG activity (normalized to the maximum EMG), and a linear least-square regression was fitted to the data. This analysis was conducted separately for each TEP, subject and for the pool data. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Results

Reorganization of polysynaptic spinal reflex networks after transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training in motor complete SCI

Figure 1 shows rectified waveform averages of the TA flexion reflex before and after training from two subjects. It is evident that transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training altered flexion reflex excitability. A pronounced reflex depression was present during the stance phase (bins 2–7) of the step cycle in both subjects.

Figure 2A shows the normalized average area of the long-latency TA flexion reflex during stepping at each bin of the step cycle from all subjects before and after training. The control EMG has been subtracted from the long-latency TA flexion reflex EMG and the resultant value is normalized to the maximum locomotor EMG. The flexion reflex after training was recorded during stepping at baseline speed (S1) and at the last training session speed (S2). The TA flexion reflex was not modulated based on bins of the step cycle (F15,94 = 1.19, P = 0.293) and was significantly different before and after training when recorded at speed S1 (F1,94 = 17.32, P < 0.001). Pairwise multiple comparison Bonferroni t tests showed that the flexion reflex was significantly different before and after training during the stance phase at bins 1, 3, 4, and 5 (P < 0.05). No statistically significant differences were found when the TA flexion reflex post-training was recorded at the speed used at the last step training session, speed S2 (F1,95 = 1.28, P = 0.259). The TA flexion reflex was moderately linearly related to the TA background EMG activity before (R2 = 0.24) and after (S1: R2 = 0.02; S2: R2 = 0.06) training (Fig. 2B). The slope and intercept of the linear relationship between the flexion reflex amplitude and TA background EMG activity were not significantly different before and after training (Fig. 2C, D), supporting that the observed changes were not the result of changes in the reflex gain or excitability threshold of flexion reflex afferent (FRA) interneurons.

A The normalized subtracted long-latency TA flexion reflex from all subjects is indicated for each bin of the step cycle during robotic-assisted stepping recorded at baseline speed (S1) before and after training and at the speed of the last training session (S2). B Linear relationship between the normalized long-latency TA flexion reflex and associated TA EMG background activity from all subjects before and after training. Each point corresponds to one bin of the step cycle. C, D Overall mean amplitude of the slope and intercept computed from the linear regression analysis. Bin 1 corresponds to heel contact. Bins 9, 10, and 16 correspond approximately to stance-to swing transition, swing phase initiation, and swing to-stance transition, respectively.

Reorganization of motor output after transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training in motor complete SCI

Figure 3 shows the TEPs normalized to the homonymous maximal TEP recorded before training at increasing stimulation intensities (input–output recruitment curves) from the left and right SOL, MG, TA, and PL muscles with subjects lying supine before and after training. Two-way ANOVA showed that TEPs were significantly different before and after training in the left TA (F1,46 = 13.14, P < 0.001), left SOL (F1,29 = 7.47, P = 0.007), right MG (F1,29 = 37.09, P < 0.001), right TA (F1,29 = 37.09, P < 0.001), and right SOL (F1,29 = 3.83, P < 0.04) muscles, supporting an increase in motoneuron output after transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training.

Figure 4 shows the overall average amplitude of TEPs at each bin of the step cycle recorded from the left and right SOL, MG, TA, MH, VL, GRC, VM, and PL muscles during assisted stepping before and after training at treadmill speeds S1 (before and after training) and S2 (after training). For TEPs recorded at the same treadmill speed S1 before and after training, two-way ANOVA showed that the phase-dependent amplitude modulation was significantly different for the left SOL (F1,47 = 22.67, P < 0.001), right SOL (F1,35 = 4.63, P = 0.038), right TA (F1,87 = 12.09, P < 0.001), right VL (F1,95 = 12.14, P < 0.001), right GRC (F1,48 = 10.51 P = 0.002), and right VM (F1,48 = 7.45 P = 0.009) muscles. For TEPs recorded at treadmill speed S1 before training and at treadmill speed S2 after training, two-way ANOVA showed that the phase-dependent amplitude modulation was significantly different for the left SOL (F1,42 = 18.75, P < 0.001), left MH (F1,95 = 8.18, P = 0.005), left PL (F1,79 = 20.12, P < 0.001), right MG (F1,33 = 9.74, P = 0.004), and right VL (F1,93 = 7.31, P = 0.008) muscles.

The overall TEP amplitude is shown for each bin of the step cycle before and after combined high-frequency transspinal stimulation and locomotor training for the soleus (A), medial gastrocnemius (B), tibialis anterior (C), medial hamstrings (D), vastus lateralis (E), gracilis (F), vastus medialis (G), and peroneus longus (H). The X-axis corresponds to the bins of the step cycle.

The linear relationship between normalized TEP amplitudes during assisted stepping and associated background EMG activity along with the slope and intercept for the ankle TEPs are indicated in Fig. 5. Only in the right TA, the slope was increased after combined training at treadmill speed S2 compared to baseline treadmill speed S1 (P = 0.022).

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that high-frequency transspinal stimulation coupled with locomotor training produced depression of the long-latency TA flexion reflex with concomitant facilitation in motor output of different motoneuron groups at rest and during assisted stepping in people with motor complete SCI.

Our findings are consistent with the TA flexion reflex depression during treadmill walking following transspinal conditioning stimulation in healthy subjects [24]. More importantly, multiple sessions of low frequency transspinal stimulation alone decreased reflex excitability of ankle extensors, increased spinal inhibition in response to repetitive afferent stimulation, and increased the output of motoneurons supplying flexors and extensors of both legs as demonstrated by the TEP recruitment curves in people with motor complete and incomplete SCI [22, 28]. Based on these findings we can theorize that transspinal stimulation training alone promotes neuronal reorganization via similar activity-dependent neuroplasticity mechanisms to that of locomotor training. Some representative neuroplasticity changes underlying motor recovery after locomotor training are anatomical and physiological changes within and outside the locomotor circuitries, including primary afferent sprouting and new synapse formation [29,30,31,32,33]. In humans, representative changes associated with motor recovery after locomotor training alone are restoration of H-reflex rate-dependent depression, improved muscle activation coordination during stepping, reduced co-contractions, and reorganization of appearance of flexor responses [3, 34, 35].

At this point we should consider the potential mechanisms that our combined intervention resulted in concomitant depression of flexor reflex excitability and facilitation of motoneurons over multiple spinal segments in people with chronic motor complete SCI. The long-latency TA flexion reflex in people with complete SCI involves a neuronal pathway similar to that described in acute spinal cat injected with L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine [36,37,38]. In spinalized cats, a late ipsilateral flexion reflex coincides with a late crossed extensor reflex under strong reciprocal inhibitory connections, and primary afferent depolarization in Ia afferent terminals is evident upon FRA stimulation [37, 39, 40]. These effects were largely mediated by changes in spinal neuronal pathways underlying the half-center of locomotion. A similar neuronal organization exists also in people with complete SCI, and as such the flexion reflex has been regarded to represent the half-center network of human locomotion [41,42,43]. The long-lasting soleus H-reflex and TA flexion reflex depression at rest and during stepping in humans upon transspinal conditioning stimulation [24, 44] support that transspinal stimulation has direct access to spinal centers contributing to walking. Thus, a possible mechanism is that of potentiation of primary afferent depolarization resulting in upregulation of presynaptic inhibition. Locomotor training alone reduces presynaptic facilitation or replaces presynaptic facilitation with presynaptic inhibition [34] and promotes a TA flexion reflex amplitude modulation during assisted stepping in humans with SCI comparable to that observed in the non-injured individuals [45]. Based on these findings and on our current results, transspinal stimulation augments the neuroplasticity of locomotor training possibly via similar mechanisms.

Importantly, the flexion reflex depression coincided with increased motoneuron output at rest (Fig. 3) and during stepping (Fig. 4) that was adjusted in amplitude based on the phase of the step cycle and treadmill speed after combined training but not similarly in left and right leg muscles (Fig. 4). Strength and amplitude of motoneuron depolarization after locomotor training alone is not similar among muscles and leg sides [46], probably related to the function of commissural interneurons and spinal motoneurons at baseline, and strength of reorganization after training [2]. Further, adaptation of motoneuron depolarization at different speeds (Fig. 4) suggest for velocity-dependent motoneuron modulation and thus for spinal neural circuits to adequately adapt to locomotion speeds, similarly to the locomotor EMG activity [47, 48]. It is possible that transspinal stimulation and locomotor training may have increased the responsiveness of motoneurons producing a more synchronized depolarization. This may have been accomplished by hyperpolarizing the spike threshold of motoneurons residing within the subliminal fringe making motoneurons more excitable to given inputs and maintain a steady depolarization to a given input and/or depolarizing the membrane potential [49]. This mechanism of action likely might be associated with changes in the slope (or gain) and excitability threshold of the FRAs, muscle afferents, and alpha motoneurons, as demonstrated after locomotor training alone [50]. The nonsignificant changes in slope and threshold may be related to the fact that SCI subjects had motor complete SCI requiring possibly more training sessions for such changes to manifest.

Limitations of the study

This was an exploratory study, and as such randomized clinical trials involving different stimulation frequencies, groups of subjects receiving stimulation or locomotor training alone or both interventions, follow-up experiments to establish the sustainability in time of these neurophysiological changes, and clinical measures of spasticity are needed. Further, while reorganization in motor complete SCI can be attributed mostly to changes in local spinal circuits, individuals with present motor activity should be tested in order to assess improvements in motor function and ability to stand and walk. Last, while depression of reflex excitability can have significant clinical benefits, behavioral and clinical side effects remain to be established via randomized clinical trials in individuals with SCI.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Knikou M. Neural control of locomotion and training-induced plasticity after spinal and cerebral lesions. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:1655–68.

Côté M-P, Murray LM, Knikou M. Spinal control of locomotion: individual neurons, their circuits and functions. Front Physiol. 2018;9:784.

Smith AC, Knikou M. A Review on locomotor training after spinal cord injury: reorganization of spinal neuronal circuits and recovery of motor function. Neural Plast 2016. 2016;12162:58

Dietz V, Wirz M, Curt A, Colombo G. Locomotor pattern in paraplegic patients: training effects and recovery of spinal cord function. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:380–90.

Nam KY, Kim HJ, Kwon BS, Park J-W, Lee HJ, Yoo A. Robot-assisted gait training (Lokomat) improves walking function and activity in people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14:24.

Hofstoetter US, Freundl B, Danner SM, Krenn MJ, Mayr W, Binder H, et al. Transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation induces temporary attenuation of spasticity in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37:481–93.

Gad PN, Kreydin E, Zhong H, Latack K, Reggie Edgerton V. Non-invasive neuromodulation of spinal cord restores lower urinary tract function after paralysis. Front Neurosci. 2018;1:432.

Kreydin E, Zhong H, Latack K, Ye S, Edgerton VR, Gad P. Transcutaneous electrical spinal cord neuromodulator (TESCoN) improves symptoms of overactive bladder. Front Syst Neurosci. 2020;14:1.

Phillips AA, Squair JW, Sayenko DG, Edgerton VR, Gerasimenko Y, Krassioukov AV. An autonomic neuroprosthesis: noninvasive electrical spinal cord stimulation restores autonomic cardiovascular function in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:446–51.

Harkema SJ, Wang S, Angeli CA, Chen Y, Boakye M, Ugiliweneza B. et al. Normalization of blood pressure with spinal cord epidural stimulation after severe spinal cord injury. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:83.

Hofstoetter US, Krenn M, Danner SM, Hofer C, Kern H, McKay WB, et al. Augmentation of voluntary locomotor activity by transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation in motor-incomplete spinal cord-injured individuals. Artif Organs. 2015;39:E176–86.

Gerasimenko YP, Lu DC, Modaber M, Zdunowski S, Gad P, Sayenko DG, et al. Noninvasive reactivation of motor descending control after paralysis. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1968–80.

Gerasimenko Y, Sayenko D, Gad P, Kozesnik J, Moshonkina T, Grishin A, et al. Electrical spinal stimulation, and imagining of lower limb movements to modulate brain-spinal connectomes that control locomotor-like behavior. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1196.

Gerasimenko Y, Gorodnichev R, Puhov A, Moshonkina T, Savochin A, Selionov V, et al. Initiation and modulation of locomotor circuitry output with multisite transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the spinal cord in noninjured humans. J Neurophysiol. 2015;113:834–42.

Formento E, Minassian K, Wagner F, Mignardot JB, Le Goff-Mignardot CG, Rowald A, et al. Electrical spinal cord stimulation must preserve proprioception to enable locomotion in humans with spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1728–41.

Kumru H, Benito-Penalva J, Valls-Sole J, Murillo N, Tormos JM, Flores C, et al. Placebo-controlled study of rTMS combined with Lokomat® gait training for treatment in subjects with motor incomplete spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res. 2016;234:3447–55.

Raithatha R, Carrico C, Powell ES, Westgate PM, Chelette KC, Lee K, et al. Non-invasive brain stimulation and robot-assisted gait training after incomplete spinal cord injury: a randomized pilot study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2016;38:15–25.

Estes SP, Iddings JA, Field-Fote EC. Priming neural circuits to modulate spinal reflex excitability. Front Neurol. 2017;8:17.

Knikou M, Conway BA. Effects of electrically induced muscle contraction on flexion reflex in human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:640–8.

Knikou M. Plantar cutaneous input modulates differently spinal reflexes in subjects with intact and injured spinal cord. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:69–77.

Gorassini MA, Knash ME, Harvey PJ, Bennett DJ, Yang JF. Role of motoneurons in the generation of muscle spasms after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2004;127:2247–58.

Knikou M, Murray LM. Repeated transspinal stimulation decreases soleus H-reflex excitability and restores spinal inhibition in human spinal cord injury. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0223135.

Knikou M, Angeli CA, Ferreira CK, Harkema SJ. Flexion reflex modulation during stepping in human spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res. 2009;196:341–51.

Zaaya M, Pulverenti TS, Islam MA, Knikou M. Transspinal stimulation downregulates activity of flexor locomotor networks during walking in humans. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2020;52:102420.

Pulverenti TS, Islam MA, Alsalman O, Murray LM, Harel NY, Knikou M. Transspinal stimulation decreases corticospinal excitability and alters the function of spinal locomotor networks. J Neurophysiol. 2019;122:2331–43.

Zehr EP, Komiyama T, Stein RB. Cutaneous reflexes during human gait: electromyographic and kinematic responses to electrical stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:3311–25.

Zehr EP, Fujita K, Stein RB. Reflexes from the superficial peroneal nerve during walking in stroke subjects. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:848–58.

Murray LM, Islam MA, Knikou M. Cortical and subcortical contributions to neuroplasticity after repetitive transspinal stimulation in humans. Neural Plast 2019. 2019. 4750768.

Rossignol S, Martinez M, Escalona M, Kundu A, Delivet-Mongrain H, Alluin O. et al. The ‘beneficial' effects of locomotor training after various types of spinal lesions in cats and rats. Prog Brain Res. 2015;218:173–98.

Côté M-P, Gossard J-P. Step training-dependent plasticity in spinal cutaneous pathways. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11317–27.

Martinez M, Delivet-Mongrain H, Leblond H, Rossignol S. Incomplete spinal cord injury promotes durable functional changes within the spinal locomotor circuitry. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:124–34.

Goldshmit Y, Lythgo N, Galea MP, Turnley AM. Treadmill training after spinal cord hemisection in mice promotes axonal sprouting and synapse formation and improves motor recovery. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:449–65.

Côté M-P, Ménard A, Gossard J-P. Spinal cats on the treadmill: changes in load pathways. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2789–96.

Knikou M, Mummidisetty CK. Locomotor training improves premotoneuronal control after chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol. 2014;111:2264–75.

Knikou M, Dixon L, Santora D, Ibrahim MM. Transspinal constant-current long-lasting stimulation: a new method to induce cortical and corticospinal plasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114:1486–99.

Andén N‐E, Jukes MGM, Lundberg A, Vyklicky L. The effect of DOPA on the spinal cord. 1. Influence on transmission from primary aflerents. Acta Physiol Scand. 1966;67:373–86.

Lundberg A. Multisensory control of spinal reflex pathways. Prog Brain Res. 1979;50:11–28.

Andén NE, Jukes MGM, Lundberg A, Vyklický L. A new spinal flexor reflex. Nature. 1964;202:1344–5.

Jankowska E, Jukes MGM, Lund S, Lundberg A. The Effect of DOPA on the spinal cord 6. Half‐centre organization of interneurones transmitting effects from the flexor reflex afferents. Acta Physiol Scand. 1967;70:389–402.

Jankowska E, Jukes MGM, Lund S, Lundberg A. The Effect of DOPA on the Spinal Cord 5. Reciprocal organization of pathways transmitting excitatory action to alpha motoneurones of flexors and extensors. Acta Physiol Scand. 1967;70:369–88.

Roby-Brami A, Bussel B. Effects of flexor reflex afferent stimulation on the soleus H reflex in patients with a complete spinal cord lesion: evidence for presynaptic inhibition of Ia transmission. Exp Brain Res. 1990;81:593–601.

Roby-Brami A, Bussel B. Inhibitory effects on flexor reflexes in patients with a complete spinal cord lesion. Exp Brain Res. 1992;90:201–8.

Knikou M. Plantar cutaneous afferents normalize the reflex modulation patterns during stepping in chronic human spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:1304–14.

Knikou M, Murray LM. Neural interactions between transspinal evoked potentials and muscle spindle afferents in humans. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2018;43:174–83.

Smith AC, Mummidisetty CK, Rymer WZ, Knikou M. Locomotor training alters the behavior of flexor reflexes during walking in human spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112:2164–75.

Knikou M. Functional reorganization of soleus H-reflex modulation during stepping after robotic-assisted step training in people with complete and incomplete spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res. 2013;228:279–96.

Lünenburger L, Bolliger M, Czell D, Müller R, Dietz V. Modulation of locomotor activity in complete spinal cord injury. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174:638–46.

Meyns P, Van De Crommert HWAA, Rijken H, Van Kuppevelt DHJM, Duysens J. Locomotor training with body weight support in SCI: EMG improvement is more optimally expressed at a low testing speed. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:887–93.

Denny-Brown DE, Sherrington CS. Subliminal fringe in spinal flexion. J Physiol. 1928;66:175–80.

Knikou M. Neurophysiological characterization of transpinal evoked potentials in human leg muscles. Bioelectromagnetics. 2013;34:630–40.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Spinal Cord Injury Research Board (SCIRB) of the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) via C32248GG and C32095GG contracts, and in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R01HD100544 awarded to MK. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZ: EMG data analysis, developed figures, and wrote the first draft of the paper. TSP performed experiments, contributed to paper writing and reviewing. MK formulated the hypotheses, designed the experiments, performed experiments and analysis, and contributed to paper writing and reviewing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zaaya, M., Pulverenti, T.S. & Knikou, M. Transspinal stimulation and step training alter function of spinal networks in complete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 7, 55 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00421-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-021-00421-6

This article is cited by

-

Soleus H-reflex amplitude modulation during walking remains physiological during transspinal stimulation in humans

Experimental Brain Research (2024)

-

Priming locomotor training with transspinal stimulation in people with spinal cord injury: study protocol of a randomized clinical trial

Trials (2023)

-

Neuromodulation with transcutaneous spinal stimulation reveals different groups of motor profiles during robot-guided stepping in humans with incomplete spinal cord injury

Experimental Brain Research (2023)

-

Brain and spinal cord paired stimulation coupled with locomotor training affects polysynaptic flexion reflex circuits in human spinal cord injury

Experimental Brain Research (2022)