Abstract

Introduction

Tachycardia, or elevated heart rate is one of the important clinical parameters considered when diagnosing pulmonary embolism (PE) based on Wells’ criteria. However, tachycardia is not highly specific and commonly presents in many other conditions.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old female with incomplete paraplegia secondary to tuberculosis (TB) spondylodiscitis presented with asymptomatic sinus tachycardia. The related medical conditions, including anaemia, acute coronary syndrome, hyperthyroidism and other infective causes had been ruled out. Deep venous thrombosis was not on the list of differentials as she showed improvements in neurological and mobility functions with no clinical signs of calf pain or swelling. She had moderate risk of acute PE based on Wells’ criteria with positive D-dimer testing and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) showing thrombus formation in the left-ascending pulmonary artery.

Discussion

Acute PE may present solely with asymptomatic sinus tachycardia in TB spondylodiscitis. This caveat should provide a high index of suspicion to prevent delay in diagnosis and prevention of more sinister complications. Early stratification based on Wells’ criteria for a possible diagnosis of acute PE is proven to be a useful approach in conjunction with clinical features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tachycardia, or elevated heart rate is one of the important clinical parameters considered when diagnosing pulmonary embolism (PE) based on Wells’ criteria [1]. However, tachycardia is not highly specific and commonly presents in many other conditions, such as infective processes, myocardial infarction, thyrotoxicosis and anaemia. PE should be suspected as one of the differential diagnoses in tuberculosis (TB) spondylodiscitis presenting with asymptomatic tachycardia as the ongoing TB infective process could similarly present with an elevated heart rate.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old female with a diagnosis of T8–T10 TB spondylodiscitis and mild neurological deficit of both lower extremities (LE) was initially treated with anti-tuberculosis pharmacological agents. However, she defaulted treatment after 2 weeks and refused further modes of intervention. Less than 2 months later, she presented with progressive lower-limb neurological deterioration and regression of mobility and daily functions. Subsequent imaging displayed worsening spondylodiscitic changes, the presence of paravertebral spine collection at T4–T11 levels and evidence of miliary TB with bilateral lung involvement. Neurological findings in accordance to the standard assessment of International Standard for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) showed the patient to have incomplete paraplegia impairment with sensory level at T8, bilateral L2 muscle strength of grade 1, L3 muscle strength of grade 4 with L4, L5 and S1 muscle strength of grade 0 [2]. Based on ISNCSCI assessment, she exhibited clinical features of American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) C.

The patient underwent minimally invasive spine stabilisation (MISt) with pedicle screw insertion at levels T3 to L1. Anti-tuberculosis medications were recommenced with additional anti-tuberculosis agents to counter previous non-compliance issue. Thromboembolic deterrant stockings (TEDS) were given at the beginning of neurological deterioration, but pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis was not prescribed in view of incomplete paraplegia and preservation of bed mobility function. At 1 week post surgery, she remained having impairment of incomplete paraplegia and was classified as AIS C but with improving neurological function. Sensory level was at T11 and LE key muscles strength based on right and left distributions were grade 2 and 1 for L2, grade 5 and 4 for L3, grade 1 and 0 for L4, grade 1 and 0 for L5 and grade 1 and 0 for S1. By the second week post surgery, she was transferred into a rehabilitation ward for intensive rehabilitative therapy. At this point, she continued to have incomplete paraplegia but further recovery of neurological function was observed from AIS C to AIS D with consistent sensory level at T11. Bilateral L2, L3, L4 and L5 muscle strength were grade 4, 5, 3 and 4 correspondingly. Muscle strength for S1 was grade 3 and 1 for right and left, respectively. These improvements enabled her to perform functional seated activities with minimal assistance. Although having incomplete paraplegia impairment, she was able to perceive bladder and bowel sensations. She achieved urinary continence by voluntary voiding with no significant residual urine. However, she required regular suppository laxative for bowel regulation.

At the third week post surgery, she developed constant sinus tachycardia in the absence of cardiopulmonary symptoms with baseline heart rate ranging from 110 to 120/min. Several differential diagnoses for asymptomatic sinus tachycardia were ruled out, including anaemia, acute coronary syndrome, hyperthyroidism and infective causes as summarised in Table 1. Several initial investigations showed sinus tachycardia in the absence of any ischaemic changes, near-normal range of haemoglobin level with mild iron deficiency anaemia picture and downward trend of inflammatory markers. Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) was not on the list of differentials as the patient showed evidence of neurological recovery and mobility improvement in the absence of calf pain or swelling. Sinus tachycardia persisted with heart rate as high as 140/min, particularly after rehabilitation therapy sessions, which hindered her ability to achieve higher functional outcomes in shorter duration.

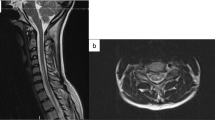

A possible diagnosis of acute PE was inferred based on Wells’ criteria in which she was stratified as moderate risk. D-dimer testing was positive and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) confirmed PE with formation of thrombus in the left-ascending pulmonary artery measuring 1.9×0.3 cm (Fig. 1). Rivaroxaban was prescribed and tachycardia gradually resolved within 1 week of treatment. Novel anticoagulation therapy was preferred in view of lower risk of adverse effects from drug interactions with ongoing anti-TB medications. After more than 4 weeks of intensive inpatient rehabilitation, the patient achieved short-distance therapeutic ambulation using forearm rollators and independent functional activities at seated level. There were no subsequent changes in the skin or size of LE throughout the treatment course; hence, venography or Doppler ultrasonography were not considered necessary as management would otherwise remain unchanged. She completed 6 months of anticoagulation therapy with regular outpatient haematology review.

Discussion

Heart rate is an important and readily available parameter for diagnosis of acute PE [1]. Tachycardia reportedly occurred in up to 33% of 334 hospitalised patients with confirmed acute PE, however, its presentation was in parallel with other observed clinical features, commonly tachypnoea and hypoxia [3]. Sinus tachycardia was the sole clinical sign portrayed in our patient illustrated here. The presence of TB infection may masquerade the ongoing acute PE, as tachycardia is a common presentation in both conditions.

By ruling out other common causes associated with asymptomatic tachycardia, the patient’s risk for development of acute PE is considered moderate as she met two of the seven criterion in Wells’ criteria: (1) heart rate of more than 100/min, and (2) surgery in the previous 4 weeks. Wells’ criteria is a scoring system originally developed to stratify patients into low, moderate or high probability of PE and was validated to have moderate inter-rater agreement [4]. Revisiting one of the criterion in Wells’ criteria pertaining to immobilisation for at least 3 days, it is arguable whether this specific criteria was met since the patient had shown improvements in neurological as well as functional mobility, particularly with bed mobility and sitting activities. Nevertheless, immobilisation and surgery share a similar criterion under the Wells’ criteria scoring system, hence, the presence of immobilisation would not lead to an additional risk score.

Thrombogenic consequences and haemostatic complications in TB are postulated by the increased risk of endothelial vessel injury secondary to its systemic hypercoagulability effect, but pulmonary TB (PTB) is rarely linked to DVT [5]. However, PE has been reported in pulmonary TB, whereby most cases displayed three or more clinical features of PE, compared to the sole sinus tachycardia feature observed in our patient [6]. On the other hand, DVT is common in acute spinal cord injury with reported incidence ranging from 14.3% to 33.3% [7,8,9]. A restrospective study observed development of PE in undiagnosed DVT among asymptomatic acute SCI patients and mostly occurred between 15 and 90 days post injury [10]. Spondylodiscitis imposes a higher risk for DVT development due to the possible involvement of neurological deficits in LE. In this case, she showed improvements both in her LE motor strength and bed mobility function before the presentation of sinus tachycardia.

Pathophysiologically, our patient is at risk for venous thromboembolism formation in view of miliary TB changes involving both lungs and spine which is associated with a hypercoagulable state [11]. We postulate that the reduced mobility function from paraplegia in addition to a hypercoagulable state secondary to underlying TB spondylodiscitis might initially induce development of asymptomatic DVT in LE, in which further modalities are needed for confirmation. It is not uncommon for DVT to develop in the absence of clinical manifestations. A total of 29 out of 127 patients with acute SCI were detected to have asymptomatic DVT diagnosed from phlebography [9]. It may be possible that neurological recovery and resumption of LE function in combination with physical activity, induced a small embolus from LE to the pulmonary vasculature, thus causing pulmonary embolism.

In acute PE, elevated heart rate is not only a clinical parameter for diagnostic purposes but also serves as one of the prognosticators for prediction of mortality outcome, principally in-hospital mortality [12]. Retrospectively, our patient falls under low-mortality risk based on Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) [13]. Although resolution of tachycardia seems imperative, the clinical inference from heart-rate normalisation in reducing the risk of PE-related mortality is yet to be established. The average duration for normalisation of elevated heart rate is yet to be ascertained, but asymptomatic sinus tachycardia in our case resolved within 1 week of anti-coagulation treatment.

In conclusion, acute PE may present solely with asymptomatic sinus tachycardia in patients with TB spondylodiscitis. Thus, a high index of suspicion is necessary to prevent delay in diagnosis and prevention of more sinister complications. Early stratification based on Wells’ criteria for a possible diagnosis of acute PE is proven to be a useful approach in conjunction with clinical features.

References

Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Stiell I, Dreyer JF, Barnes D, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:98–107.

Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A, et al. International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46.

Bajaj N, Bozarth AL, Guillot J, KojoKittah J, Appalaneni SR, Cestero C, et al. Clinical features in patients with pulmonary embolism at a community hospital: analysis of 4 years of data. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2014;37:287–92.

Wolf SJ, McCubbin TR, Feldhaus KM, Faragher JP, Adcock DM. Prospective validation of wells criteria in the evaluation of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:503–10.

Gupta KB. Thromboembolism in tuberculosis: a neglected comorbidity. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2014;56:5–6.

Bishav M, Kashyap A, Jagdeep W, Mahajan V. Pulmonary embolism in cases of pulmonary tuberculosis: a unique entity. Indian J Tuberc. 2011;58:84–87.

Colachis SC, Clinchot DM. The association between deep venous thrombosis and heterotopic ossification in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1993;31:507–12.

Waring WP, Karunas RS. Acute spinal cord injuries and the incidence of clinically occurring thromboembolic disease. Paraplegia. 1991;29:8–16.

Yelnik A, Dizien O, Bussel B, Schouman-Claeys E, Frija G, Pannier S, et al. Systematic lower limb phlebography in acute spinal cord injury in 147 patients. Paraplegia. 1991;29:253–60.

Aito S, Pieri A, D’Andrea M, Marcelli F, Cominelli E. Primary prevention of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in acute spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:300–3.

Kager LM, Blok DC, Lede IO, Rahman W, Afroz R, Bresser P, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis induces a systemic hypercoagulable state. J Infect. 2015;70:324–34.

Keller K, Beule J, Coldewey M, Dippold W, Balzer JO. Heart rate in pulmonary embolism. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10:663–9.

Jimenez D, Yusen RD. Prognostic models for selecting patients with acute pulmonary embolism for initial outpatient therapy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14:414–21.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to express their gratitude to the whole spinal cord injury rehabilitation team member for the continuous effort and care for the patient involved in the case report during the inpatient stay at the rehabilitation ward.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmedy, F., Ahmad Fauzi, A. & Engkasan, J.P. Asymptomatic tachycardia and acute pulmonary embolism in a case of tuberculosis spondylodiscitis. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 4, 43 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0074-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-018-0074-7