Abstract

Study design

Qualitative, semi-structured interviews.

Objectives

Neuropathic pain (NP) can be psychologically and physically debilitating, and is present in approximately half of the spinal cord injured (SCI) population. However, under half of those with NP are adherent to pain medication. Understanding the impact of NP during rehabilitation is required to reduce long-term impact and to promote adherence to medication and psychoeducation recommendations.

Setting

United Kingdom.

Methods

Five males and three females with SCI and chronic NP, resident in rehabilitation wards at a specialist SCI center in the United Kingdom, took part. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants less than 15 months post-SCI (mean = 8.4 months). Verbatim transcripts were subject to interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA).

Results

Three super-ordinate themes were identified, mediating pain and adherence: (1) the dichotomy of safety perceptions; (2) adherence despite adversity; and (3) fighting the future. Analyses suggest that experience of the rehabilitation setting and responsiveness of care shapes early distress. Attitudes to medication and psychosocial adjustment are relevant to developing expectations about pain management.

Conclusions

Enhancing self-efficacy, feelings of safety in hospital, and encouraging the adoption of adaptive coping strategies may enhance psychosocial and pain-related outcomes, and improve adherence to medication. Encouraging adaptive responses to, and interpretation of, pain, through the use of interventions such as coping effectiveness training, targeted cognitive behavioral pain management, and acceptance-based interventions such as mindfulness, is recommended in order to reduce long-term reliance on medication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 60% of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) are affected by chronic pain [1, 2], a significant problem that should be addressed from its onset to facilitate early adjustment to both pain and SCI. People with neuropathic pain (NP) often report difficulty managing it, describing unique sensory qualities of pain, including burning, electric, and crushing sensations [3], and these can be potentially distressing in nature. NP typically fluctuates in severity, worsening over time [2], with between 34 and 41% of the SCI population with NP in the early stages of rehabilitation living with it at 5 years post-injury [4], signifying a potential correlation and the need for early intervention/management.

Despite its prominence, and the limited effectiveness of medication [5], common practice first-line treatment for NP remains targeted pharmacological pain management [6]. Such approaches are essential, given the structural and biochemical changes associated with nerve damage after SCI [7]. However, poor adherence is common in pain populations [8]; fewer than half (43%) of people with NP were compliant with their drug regimes in one study [9]. Adherence is related directly to the participants’ beliefs regarding the necessity of, and concerns regarding, medication [10], indicating that psychosocial factors mediate pain-related behaviors and its persistence. Perceptions of low pain control and catastrophic thinking have been identified as factors playing a role in outpatients with SCI [11]. Other work has suggested that variables such as functional status, emotional status, and coping variables, do not predict chronic pain [1]. However, the majority of research is focused on outpatients, as opposed to early rehabilitation. Given the correlation between pain during rehabilitation and its long-term presence, there may exist a critical time window for responding and mitigating the effects of pain, thus facilitating the adjustment process.

Previous qualitative work has explored experiences of social support following SCI [12], pain management [13], memories of pain [14], NP acceptance [15], the lived experience of NP itself by people with SCI living in the community [16], and the use of metaphorical language when communicating NP [17]. Despite evidence that 70% of patients report NP within 6 months of injury, and often find nothing to help alleviate pain [18], no published work has considered the experiences of those in the early stages of rehabilitation from a qualitative perspective. This work will serve to highlight patient understandings during a critical time, where they are learning how to navigate life with SCI and NP, and focus future work on key aspects identified as significant by those living with NP. This can also aid healthcare staff in identifying and correcting any false understandings, and contribute toward minimizing the risk of distress caused by chronic pain as an outpatient following rehabilitation.

This study, therefore, presents the results of analysis of eight verbatim transcripts of interviews with inpatients with SCI and NP in rehabilitation at a specialist spinal center in the United Kingdom. The data were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) [19] in order to enrich current understanding of NP from the perspective of those who are in the early stage of adjustment to SCI. This study aims to identify what is most important to those living with NP during rehabilitation in terms of impact and management.

Method

Participants

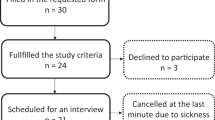

Participants were recruited from The National Spinal Injuries Centre. Inclusion criteria were: inpatient status, presence of NP for a duration of at least 3 months (adhering to the International Association for the Study of Pain [20], definition of chronic pain), over 18 years of age; and English speaking. Participants were not recruited if they held any significant cognitive impairment, mental illness, or head injury. People meeting the inclusion criteria were approached by members of the direct care team, and directed to the researchers for further information. Of the 11 patients contacted, three declined to participate and eight were interviewed. Due to the large amount of data obtained, and IPA’s detailed, idiographic approach to analysis, this sample size is considered appropriate, in accordance with recommendations of a small sample size [21]. Five participants were male, and three were female. Participants have been given pseudonyms in order to preserve confidentiality and anonymity. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Materials

Interview schedule

In order to elicit in-depth, detailed information, an interview schedule was developed and piloted with two individuals with SCI to ensure questions were appropriate and to trial the length of the interview. This is presented in Table 2.

Procedure

Local ethical approval was secured for the study from The National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (ref: 13/LO/0558), the local Research and Development office (RXQ/549), and The University of Buckingham.

A member of the direct care team identified and approached eligible patients with information regarding the study and asked if they would consider taking part, after which patients were provided with detailed information and offered time to consider their consent. Written, informed consent was obtained, and interviews were conducted in private rooms. Interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min.

Interviews were audio-recorded and participants were given freedom to lead the interview, unrestricted by the imposition of topics, such that discussion centered on what participants felt was most important in their experience [21]. Participants were able to discuss what was of importance to them, and focus upon their own personal experience and the meanings of NP to them and their experience, as recommended by Smith et al. [21]. Any identifying information (e.g., participants, friends and families, and healthcare professionals) has been anonymized.

Data analysis

The systematic approach to IPA recommended by Smith, Flowers & Larkin [21] was followed. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and read a number of times to ensure familiarity with the data. Analytic notes and reflections (descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual) were made to aid the emergence of themes. Searching for similarities and differences across emergent themes then enabled super-ordinate themes to be developed, representing aspects of the experience considered most important from participants’ perspectives. This process was completed in an idiographic manner. Following analysis of all transcripts, a cross-case analysis was conducted, establishing patterns, and identifying themes present across at least half of the sample, as well as convergences and divergences across cases. A table was generated, within which were super-ordinate and sub-ordinate themes, with illustrative quotes. Throughout this process, the data were constantly revisited (i.e., after analytical notes, emergent themes, and super-ordinate themes were developed) to ensure that themes remained grounded in the data and reflected participants’ accounts [21].

IPA is interpretative in nature, suggesting that individual researchers may interpret data differently, due to differences in personal backgrounds. Therefore, as recommended by Smith, Flowers, & Larkin [21], a reflective diary was used in a determined effort to “bracket-off” prejudgments and information learned from previous interviews. To achieve rigor and quality in the analysis, two independent auditors, both of whom have experience with people with SCI, or IPA, validated super-ordinate themes and corresponding quotations to ensure themes were grounded in the data. Interpretations were discussed with the first author to illuminate areas of the experience that may have been more easily identifiable to the auditors. The interpretations presented here are considered credible and meaningful, although it is acknowledged that these are not the only interpretations of the data.

Ethical considerations

Confidentiality of interviews and anonymity was ensured throughout the study. The process of thinking about, and discussing pain could cause some distress, and participants were offered the opportunity for a close family member to be present during their interview, if they wished. They were informed of their right to pause the interview and take a break, and to withdraw at any point, and have their data destroyed. Participants were provided with a debriefing form containing contact details of the authors, as well as an independent SCI charity, should they wish to discuss the research, available support, or any issues arising from their interview. No participants chose to have a family member present, nor voiced distress arising from the interview, or asked to have their data withdrawn.

Results

Three super-ordinate themes arose from the data: (1) the dichotomy of safety perceptions; (2) adherence despite adversity; and (3) fighting the future. Super-ordinate themes and their corresponding sub-ordinate themes are presented in Table 3.

The dichotomy of safety perceptions

Participants’ descriptions suggested that the environment was an important factor in their overall sense of safety, emotional security, and the immediate availability of care as and when needed; during flare ups of pain, for example. This was accompanied by positive perceptions of staff as empathetic and compassionate, which also aided psychological well-being. Such perceptions could play a role in the interpretation and experience of pain, as well as the extent of adherence to pain management.

Confinement in “prison” vs. shelter in a “safe haven”

For those who perceived hospital negatively, confinement and desires to leave hospital as soon as possible were characteristic of their discussions. When asked if there was anything that could help him cope with pain, Jimmy’s interpretation used powerful catastrophic imagery:

Getting out of this ward would be important. I mean, it’s like being in a cell, 24/7. I know the staff are very good, but like [..] how often are you going to see the staff? You know, they’re busy themselves … The nurses are running around, like all the time they’re here. They don’t stop [Jimmy].

Jimmy insinuates that because he perceives the rehabilitation staff as being very busy, he feels he cannot rely on them to meet his needs. The imagery of being in a prison cell implies a sense of extreme restriction and isolation.

Yet, the rehabilitation environment comforted other participants, leading to an interpretation of hospital as a “safe haven”:

I am happy here though, I feel comfortable. Probably just knowing there are nurses around if I need them … At home, I do worry, like if something goes wrong, there’s nobody there to help me cope with the pain [Alice].

Alice is reassured that staff can meet her needs. As a result of the immediate access to knowledgeable staff, she feels able to cope with pain. The lack of direct access to such people when at home causes her to feel distressed, insecure and anxious. This also suggests that she holds an external locus of control with regard to pain management, relying on others to provide her with pain relief and suggesting she does not feel equipped to do this herself.

Like Alice, George also felt safe in hospital:

This hospital is great, absolutely perfect this hospital is. Yep. They’ve dealt with spinal injuries in the past, this is what it was made for. They understand, you come here if you’re in my condition because they expect it, they’ve dealt with it, and they can deal with it as and when you need it, any time of day [George].

George was comforted by the specialist nature of the hospital and experience of the staff working in the unit, as well as their constant availability. The factors acted as a potential stress buffer, allowing him to feel safe and as though any pain flares could be managed as necessary. Thus, he felt able to focus upon rehabilitation with few concerns.

Positive perceptions of staff

Participants often judged staff in a positive light, regarding them as valuable in terms of their ability to help with pain and injury coping. Alice’s quote in the theme above also reflects positive perceptions of staff, in that personal characteristics of staff, particularly their knowledge and immediate availability, contributes toward feelings of security and being cared for. Jimmy also had strong relationships with his rehabilitation team, despite perceiving the hospital environment as restrictive (prison-like, see page 10):

The physio is good, at least you know the people are trying to help you, you know. They’re so dedicated, the people that do it. They care, quite a lot actually, 100%. They’re very good. It makes me feel better, they’re supposed to be coming round today, and they can come round whenever you need them. I find them very good, and not only just the exercise they give you, it’s the way they talk to you, they’re very, very helpful. I’ve got very strong relationships with them; they’re very good [Jimmy].

Jimmy suggests that, despite perceiving hospital as prison-like, his experience has been enhanced by staff who are seen as responsive, helpful, and facilitate the rehabilitation process. The rapport and social relationships built between himself and the staff may be beneficial for his psychological well-being. Such positive judgments appear to be mediated by perceptions of staff knowledge and skill, empathy, and compassion. This theme highlights the importance of these qualities in staff and the surrounding environment as key to overall feelings of psychological containment, mitigating distress, and belief in the ability to cope with pain and the demands of rehabilitation.

Adherence despite adversity

There was a spectrum of reasons for and against adherence discussed in relation to pharmacological treatment of NP, with participants identifying themselves at two opposite and extreme points. The majority voiced perceptions of medication as ineffective, expressing concerns regarding side-effects, which led to either reduced adherence, or a resignation to adherence due to perceptions of no alternative options. At the other end of the spectrum, others found satisfactory relief in their drug regime, which increased adherence. Centrally, however, participants expressed a desire for complete pain relief, despite the extent to which it was presently managed. This theme demonstrates the importance of understanding patient expectations of pain relief.

Desperation and hopelessness

Five of the eight participants felt that their pain medication was inadequate, with a high degree of focus placed on hopes for total pain relief:

I was on 5 mg [pain medication] (Descriptive information provided by the authors), and I said it’s not enough, so they put me on 10, and it’s still not enough, so they put me on 15, and that still isn’t enough, and I think 20 is the most you can have. But like I said, I don’t want to take any more. There’s no more medication that can help [Alice].

Alice highlights both her ambivalence about the effectiveness of medication and her desperation for adequate pain relief. Her focus is on medication as the sole provider of pain relief, which she admits is not a helpful approach. Alice’s quotes illustrate both her hopelessness toward medication to bring pain relief, reflecting a general hopelessness about how to manage her pain, and perception of a lack of alternative.

George voiced concerns regarding the ineffectiveness of medication and lack of alternative:

They [hospital staff] don’t know what to do to stop the pain. There’s just not a painkiller on the market for this sort of pain. It’s not as if you can take an aspirin or, like the old days, or paracetamol. They don’t work, don’t touch it [George].

George’s statements indicate a sense of futility about pain control on a global and personal scale, as well as his external locus of control, seeing staff as those responsible for his pain relief. Such a view emphasizes a need for psychosocial management to be further addressed during rehabilitation, which may mitigate the effect of such perceptions on adherence and other health-related behaviors.

Resigned and indifferent

Two participants acknowledged the benefits of medication, but felt resigned to taking it as a last resort, or the only option. When asked how she manages her pain, and how she feels about taking medication, Jennifer responded:

Nothing I can do really. Just have to take tablets [Jennifer].

I don’t like it, I take a lot. I don’t like it, but, you just have to take it. If you didn’t you’d be a screaming loony. Well you would, because you couldn’t take the pain [Jennifer].

Jennifer indicates that she would prefer not to rely on medication, but presents a resignation that if she did not take it her pain would be unmanageable. Despite her negative perception of medication, the metaphor of losing her sanity suggests that pain acts as a threat to her emotional integrity, thus motivating her adherence.

In contrast, Mark was appreciative of his pain management:

I’ve been very lucky that the consultant has given me quite a heavy dose of long-term release medical prescription. I can also have morphine; you know liquid morphine, as and when I need that, every four hours. So, the pain relief has been good [Mark].

Mark had faith in his pain management regime, comforted by his ability to take strong medication as and when needed. He refers to being “lucky,” suggesting that he may have been aware of others without good pain control, but is happy with his own regime, despite it being a “heavy dose.” The variance of experiences within this theme suggest that attitudes toward medication vary widely and are linked to hopelessness and hopefulness and may affect adherence to medication even during the inpatient rehabilitation phase.

Fighting the future

Participants’ discussions often became future-oriented and presented uncertainty around whether pain would persist. Some participants perceived their pain as a temporary phenomenon that would not persist, while others did not feel that pain interfered with their rehabilitation, and acknowledged that it might not resolve. Regardless of their stance, participant narratives reflected a fight against pain to engage in forward-planning and rehabilitation.

Pain is impermanent

Five of the eight participants considered their pain a temporary presence, and had hopes for complete pain relief, despite the potential persistence of NP:

The pain won’t be there when I get home. I’m certain that it won’t … I think that by the time I leave, I’m getting better and better, and the pain will go away … It’s not an unknown thing, it will go away [Amir].

Haven’t accepted it, just putting up with it… I hope it’s more temporary for me. I hope so, I hope so [Jennifer].

Amir discussed his future with optimism, a belief that did not allow for any consideration that NP might persist, and thus may have allowed him to focus upon rehabilitation. Such perceptions may also prevent the development of adaptive coping strategies, pain management, and acceptance of both injury and NP, should NP persist. Jennifer also voiced uncertainty regarding the trajectory of NP, implying that there exists a sense of the unknown with regard to NP during inpatient rehabilitation, with many expressing desires for a pain-free future. However, should NP persist following discharge, such patients may be at risk of increased distress as a result of their expectations not being met. Patients may find that they are potentially unprepared to manage NP and adhere to pain medication and education provided throughout rehabilitation if their goal is for complete pain relief.

Pain is persistent, and I accept it

A minority of participants, David and George, expressed an understanding that NP may persist beyond rehabilitation, illustrating a need to foster improved understanding of the potential persistence of NP following SCI. Participants appeared to have accepted the likelihood that NP would persist, and had begun to prepare for a future with pain present:

Yeah, I’ve come to terms with it [pain], and I’ve come to terms that I’m going to go home, this same way, with pain [George].

When considering his discharge into the community, George voiced his acceptance of pain’s presence, suggesting that he is not necessarily overwhelmed by the idea that pain could be permanent. He remains focused on his goal of going home, rather than letting pain disrupt his rehabilitation and emotional well-being. Such acceptance could reduce NP’s interference in daily life, and improve views of the future, as well as adherence and adjustment.

Discussion

This study investigated the subjective meanings and experiences of chronic NP in inpatients with SCI, in order to explore its impact upon rehabilitation and management. Three themes emerged regarding the experience of NP: (1) the dichotomy of safety perceptions; (2) adherence despite adversity; and (3) fighting the future. The environment, and empathy and compassion from staff were significant factors for participants, and may play influential roles in pain behaviors, coping, and medication adherence. Issues surrounding medication efficacy were prominent, with many participants voicing ambivalent feelings about medication and hopes for complete pain reduction. Finally, future-oriented discussion implied that there remains some uncertainty surrounding pain’s persistence, with many participants discussing expectations of a pain-free future. This is a key issue to be discussed with patients early in rehabilitation; providing accurate information but maintaining hope while taking account of overall adjustment/readiness for information. The potential for NP to cause psychological distress in some people is also highlighted, with key influences being perceived inadequate pain relief, and the perceived restriction or limited availability of support in the hospital environment. This may interact with overall adjustment to injury and engagement in rehabilitation. The themes reflect the considerations of those with NP after SCI as they progress through rehabilitation toward discharge, and as they begin to adjust to the injury, supporting the idea that pain management approaches should be incorporated into interactions throughout the rehabilitation experience.

The first theme involved participant interpretation of their surrounding environment. Such interpretations may reflect overall appraisals in relation to coping with SCI, as well as their pain experience. Interpreting hospital positively appeared to be related to perceptions of staff availability and responsiveness as well as optimism in the ability to cope with overall consequences of SCI. Benefits of feeling safe in hospital include increased focus on recovery [23], and obtaining adequate rest [24], and suggest that feelings of safety are also related to perceptions of coping with pain and rehabilitation. Those describing hospital negatively did so using powerful metaphors, accompanied by feelings of being unable to cope with their SCI and pain, which may be associated with catastrophic thinking. Feeling safe, therefore, may be just as important as being safe [25]. It is difficult to make inferences from the emergence of this theme, due to the lack of existing research regarding patient interpretations of hospital environments [26]. The emergence of such a theme, however, suggests that it is a key issue for people in rehabilitation, and indeed cases of extended inpatient care. Environmental factors, particularly around the responsiveness of care and perceived quality of relationships with staff should, therefore, be considered, with more research needed exploring perceptions of inpatient environments in order to better understand their relationship with coping and pain management.

Factors mediating perceptions of staff and sense of security included knowledge, trust, presence, empathy, and compassion, which may influence how people learn to manage NP. Some participants were comforted by the expert knowledge they perceived the staff to have; others remained aware that staff were not always readily available if they needed them. A recent concept analysis of patient feelings of safety identified similar themes [27], highlighting their prominence among hospitalized patients. Building rapport and trust are key goals for rehabilitation staff, and can improve patient satisfaction and treatment compliance, allowing patients to achieve better outcomes from their care [28]. These findings suggest that such psychosocial factors are linked with how people cope with pain after SCI.

Empathy and compassion were identified as important to participants, both having the potential to play significant roles in encouraging health benefits such as treatment adherence [29]. Olsen and Hanchett [30] found negative relationships between nurse-expressed empathy, and distress experienced by the patient, and between patient-perceived empathy and distress experienced by the patient, thus supporting this finding. Improving staff awareness of interpersonal interactions and promoting patient-perceived empathy and compassion, as well as communication, rapport, and friendliness, should be encouraged [31]. These characteristics were acknowledged as beneficial to psychosocial well-being by those in this study, and were elicited in response to questioning about what aids pain coping.

Adherence despite adversity concerned a core belief that pain relief was the most important mechanism to cope with pain, often associated with ambivalence toward medication. Many participants saw medication as the only option to manage pain, highlighting a discrepancy between patient expectations and the goals of rehabilitation. Adherence behavior was variable depending on such competing beliefs, suggesting that non-adherence behavior could be presenting itself prior to discharge from hospital, and prescribers and rehabilitation staff should address pain-related motivations and what patients consider a satisfactory outcome in order to maximize adherence. Further work is required to establish whether pre-discharge adherence behavior is a useful indicator of problematic non-adherence post-discharge.

Many participants voiced a dislike of medication, either refusing to adhere, or continuing to take it despite their aversion. Patients, however, often have fears of not being believed regarding pain, or burdening care staff, which may become barriers to providing complete information regarding adherence [32, 33], and impact the patient–staff relationship. Participants in this study were provided with individualized goal-focused rehabilitation programmes by the treating center, during which a holistic pain management approach is promoted. However, this study suggests that those who are most distressed by the NP may not be as receptive to pain management messages, and it may be helpful to examine the messages that prescribing staff give to counter the perception of total pain relief as a primary goal. Fostering effective patient-clinician communication and offering patients informed choice may be of longer-term benefit. Such improvements may promote a collaborative approach in pain management [34], along with improved adherence and pain management.

Participants discussed hopes surrounding NP post-discharge. Those who felt pain was manageable did not appear distressed, and felt able to make plans. This has been associated with patients taking a more active approach to pain management, and using less medication [35]. While chronic pain is correlated with depressed mood, increased self-efficacy in individuals with SCI can serve to mitigate the complex interaction between chronic pain on mood [36], and is positively correlated with life satisfaction [37]. Levels of self-efficacy, however, are reduced in those with SCI, compared to the general population [38], suggesting that those distressed by NP may have lower self-efficacy and high external locus of control. Acceptance of injury is commonly addressed in rehabilitation; improving pain self-efficacy may moderate the extent to which pain interferes with their lives [39] and could act as a long-term stress buffer.

Others discussed hopes for a pain-free future, which may prevent adaptation to NP and SCI in the long term. Coping effectiveness training [40] teaches appraisal and cognitive behavioral coping skills, such that a client is able to choose the optimum coping response in particular situations. This has been shown to improve psychological adjustment to SCI [41]. Participants expressing this theme may have used coping strategies that may be considered maladaptive (such as delaying help-seeking), and suggests that both acceptance of pain and acceptance of injury may be associated as early as during inpatient rehabilitation. Enabling acceptance of pain and the adoption of approach-focused coping strategies in relation to pain, as well as general adjustment to injury, could be helpful for this group.

Limitations

As the small sample was primarily made up of people aged over 60 (reflective of the changing demographic of an ageing SCI population), the results may not be representative of the wider SCI population. The self-selecting sample also suggests that these participants may have been more willing to talk to a stranger about their experiences than the non-volunteering population, and that those effectively managing NP were less motivated to participate. A replication study involving a sample with a wider variety of levels of injury may be useful to explore variance in experience.

The nature of the IPA methodology limits the degree to which conclusions can be drawn about causal links between themes. Future work should, therefore, quantitatively explore the relationship between environmental perceptions, including perceived empathy and compassion of staff in relation to perceived self-efficacy in the management of NP, and how patient perceptions about the goals of pain medication and perceived acceptable nature of the outcome influence adherence to pain medications. It may also be of benefit to interview staff who work with people with SCI, to gain a 360° understanding of NP in rehabilitation, and of potential barriers to care and how these might be overcome.

Conclusion

Participants resident in a rehabilitation facility expressed concerns in three broad domains in relation to NP; pain relief and ambivalence about medication, interpretations of the environment and staff empathy/compassion, and the potential transitory or persistent nature of pain in the future. The issue of how medication is used for pain relief, even in this relatively early stage of transition from acute to chronic pain, seems to be important in terms of managing distress and future chronic pain. This is a significant issue, since those living with NP following SCI are likely to continue experiencing it. Psycho-educational interventions based around the biopsychosocial model of pain should be tailored to each individual’s unique needs and experience, with a clear systematic message presented early in rehabilitation that long-term medicating may not be a useful goal. Emphasis should be placed on alternative strategies and on fostering moving toward acceptance.

References

Kennedy P, Frankel H, Gardner B, Nuseibeh I. Factors associated with acute and chronic pain following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:814–7.

Modirian E, Pirouzi P, Soroush M, Karbalaei-Esmaeili S, Shojaei H, Zamani H. Chronic pain after spinal cord injury: results of a long-term study. Pain Med. 2010;11:1037–43.

Bennett M. The LANSS pain scale: the Leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001;92:147–57.

Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ. A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain. 2003;103:249–57.

Siddall PJ, Middleton JW. A proposed algorithm for the management of pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:67–77.

Cardenas DD, Jensen MP. Treatments for chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injury: a survey study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:109–17.

Vierck CJ, Siddall PJ, Yezierski RP. Pain following spinal cord injury: animal models and mechanistic studies. Pain. 2000;89:1–5.

Broekmans S, Dobbels F, Milisen K, Morlion B, Vanderschueren S. Medication adherence in patients with chronic non-malignant pain: is there a problem? Eur J Pain. 2009;13:115–23.

Gharibian D, Polzin JK, Rho JP. Compliance and persistence of antidepressants versus anticonvulsants in patients with neuropathic pain during the first year of therapy. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:377–81.

Horne R, Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–67.

Molton IR, Stoelb BL, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Raichle KA, Cardenas DD. Psychosocial factors and adjustment to chronic pain in spinal cord injury: replication and cross-validation. J Rehab Re Dev. 2009;46:31–42.

Rees T, Smith B, Sparkes AC. The influence of social support on the lived experiences of spinal cord injured sportsmen. Sport Psychol. 2003;17:135–56.

Lofgren M, Norrbrink C. “But I know what works”--patients’ experience of spinal cord injury neuropathic pain management. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2139–47.

Sparkes AC, Smith B. Men, spinal cord injury, memories and the narrative performance of pain. Disabil Soc. 2008;23:679–90.

Henwood P, Ellis JA, Logan J, Dubouloz CJ, D’Eon J. Acceptance of chronic neuropathic pain in spinal cord injured persons: a qualitative approach. Pain Manag Nurs. 2012;13:215–22.

Hearn JH, Cotter I, Fine P, Finlay KA. Living with chronic neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:2203–11.

Hearn JH, Fine P, Finlay KA. The devil in the corner: a mixed-methods study of metaphor use by those with spinal cord injury-specific neuropathic pain. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:973–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12211.

Celik EC, Erhan B, Lakse E. The clinical characteristics of neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:585–9.

Smith JA. Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychol Health. 1996;11:261–71.

International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of Chronic Pain, Second Edition (Revised); 2011 (accessed 7 Aug 2014). Available at http://www.iasppain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673&navItemNumber=677.

Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological. Analysis: theory, method and research. London: Sage; 2009.

American Spinal Injury Association. Reference manual for the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (Revised 2003). Chicago: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003.

Norrbrink C, Lundeberg T. Acupuncture and massage therapy for neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury: an exploratory study. Acupunct Med. 2011;29:108–15.

Burfitt SN, Greiner DS, Miers LJ, Kinney MR, Branyon ME. Professional nurse caring as perceived by critically ill patients: a phenomenologic study. Am J Crit Care. 1993;2:489–99.

Granberg A, Engberg IB, Lundberg D. Acute confusion and unreal experiences in intensive care patients in relation to the ICU syndrome. Part II. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1999;15:19–33.

Lasiter S. Older adults’ perceptions of feeling safe in an intensive care unit. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:2649–57.

Mollon D. Feeling safe during an inpatient hospitalization: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:1727–37.

Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27:237–51.

Squier RW. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationships. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:325–39.

Olsen J, Hanchett E. Nurse-expressed empathy, patient outcomes, and development of a middle-range theory. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1997;29:71–6.

Wassenaar A, Schouten J, Schoonhoven L. Factors promoting intensive care patients’ perception of feeling safe: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51:261–73.

Gagliese L. Pain and aging: the emergence of a new subfield of pain research. J Pain. 2009;10:343–53.

Weiner DK, Rudy TE. Attitudinal barriers to effective treatment of persistent pain in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2035–40.

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–97. 4

McCracken LM. Learning to live with the pain: acceptance of pain predicts adjustment in persons with chronic pain. Pain. 1998;74:21–7.

Craig A, Tran Y, Siddall P, Wijesuriya N, Lovas J, Bartrop R et al. Developing a model of associations between chronic pain, depressive mood, chronic fatigue, and self-efficacy in people with spinal cord injury. J Pain. 2013;14:911–20.

Peter C, Müller R, Cieza A, Post MWM, van Leeuwen CMC, Werner CS, et al. Modeling life satisfaction in spinal cord injury: the role of psychological resources. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2693–705.

Geyh S, Nick E, Stirnimann D, Ehrat S, Müller R, Michel F. Biopsychosocial outcomes in individuals with and without spinal cord injury: a Swiss comparative study. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:614–22.

Hurt CS, Burn DJ, Hindle J, Samuel M, Wilson K, Brown RG. Thinking positively about chronic illness: an exploration of optimism, illness perceptions and well-being in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19:363–79.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984.

Kennedy P, Duff J, Evans M, Beedie A. Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2003;42:41–52.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants and the staff at The National Spinal Injuries Centre for their time and co-operation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hearn, J.H., Finlay, K.A., Fine, P.A. et al. Neuropathic pain in a rehabilitation setting after spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of inpatients’ experiences. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 3, 17083 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-017-0032-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-017-0032-9