Abstract

Study design

Scoping review.

Objectives

The objective of this study is to report on the extent, range and nature of the research evaluating peer-led interventions following spinal cord injury, and to categorize and report information according to study design, peer role, intervention type and intended outcomes.

Methods

Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews was used. Original research studies of a peer-led intervention published between 2010 and present were included. CINAHL Plus, Ovid MEDLINE and PsycINFO were searched using key terms, in addition to citation checks. Data were extracted against a previously published consolidated typology.

Results

Significant heterogeneity in studies (n = 21) existed in aims and methods. Two studies reported on randomized controlled trials with relatively robust sample sizes and qualitative methodology was common. Peer role was frequently described as ‘peer support’, but there was variation in the description and duration of the interventions, complicating the categorization process. The majority of interventions were conducted one to one (n = 15). Studies most commonly aimed to address community integration (n = 15) and health self-management outcomes (n = 10).

Conclusions

A small number of studies were eligible for review, although increasingly with rigorous designs. The nature of the peer mentor and mentee experiences were explored, and the interaction between the two, offering rich insights to the value of lived experience. Further work refining typology describing intervention type, peer roles and outcomes would facilitate replication of programmes and study designs, enabling statistical synthesis and potentially strengthening the credibility of peers as a viable resource in in-patient and community settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing recognition that peer mentors have an important role in facilitating the participation, health and well-being of people who have recently acquired a spinal cord injury (SCI) [1, 2]. Peer mentoring typically involves people who have successfully faced a similar experience to that of the mentee and, as a result, are well positioned to provide emotional, informational, esteem and physical assistance to others [3,4,5]. Peer mentoring programmes and interventions are unique in that they formalize the valuable input of people with lived experience and are commonly delivered by a combination of volunteers and paid workers. Qualitative studies have identified that peer mentors provide hope for the future and enable people to visualize possibilities that they may not have thought achievable, e.g., being active participants in community life, returning to paid employment and improving self-efficacy, perceptions of competence and self-determination [5, 6].

There are an increasing number of documented evaluations of specific interventions that involve peers in their delivery, which can be described as peer-led interventions. Examples of these include the following: promoting physical activity following SCI [7] delivering wheelchair skills training [8]; maintaining health and preventing secondary health conditions following SCI [9, 10]; and promoting self-efficacy [11]. However, most SCI peer-delivered services are general in nature with an informal approach of support and education, most commonly provided by not-for-profit organizations. There is great variation in the components of peer-led interventions offered by different organizations and in different countries. In addition, there is minimal knowledge regarding many aspects of the interventions. For example, whether there are any theoretical underpinnings, what specific role the peer has, whether interventions are conducted in person, by telephone or virtually, how long and how often interventions are offered, whether interventions are individual or group based and what type of training the peer mentors undergo.

Peer-led interventions are usually run outside the formal system of care and fill an important service gap in long-term SCI management. However, although there is ancedotal evidence of their effectiveness, there is limited robust evaluation of these programmes [12]. A lack of standardized or detailed descriptions of peer-led interventions makes it difficult to perform meaningful and generalizable research. To our knowledge, there are no published international standards for best practice for SCI peer-led interventions, further compounding the difficulty in evaluating their effectiveness. In an environment of increasingly limited funding, policy makers, funders and disability service providers need solid and convincing evidence that such interventions are effective and facilitate improvements in community reintegration and overall quality of life [12].

This scoping review, therefore, aimed to report on the extent, range and nature of the research literature regarding peer-led interventions following SCI. Information was categorized and reported according to study design, peer role, type of intervention and intended outcomes. The applicability of the peer-role categories in relation to their relevance for peer-led interventions following SCI was reviewed. The literature was summarized, gaps identified and recommendations made to address limitations going forward.

Methods

Scoping reviews are increasingly being utilized as a viable alternative method of reviewing evidence on a specific topic [13]. Scoping reviews are particularly useful when an overview is needed to determine future research priorities by establishing what evidence is currently available [13] or when limited evidence exists, such as in the case of peer-led interventions [14]. A systematic review typically focuses on a well-defined research question where appropriate study designs can be identified in advance and seeks to assess the quality of the evidence. A scoping review, however, addresses broader topics where there may be many different study designs applicable, some of lower quality, and may include grey literature such as theses, government reports and policy documents [13]. There remains some criticism regarding the lack of scientific rigour of scoping reviews [15], highlighting the need for a rigorous methodological framework to ensure transparency and confidence in dissemination of findings [15].

In order to address the aims of this scoping review, the five-stage methodological framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [13] was used. The stages are as follows: 1. Develop the research question; 2. Search for relevant literature; 3. Select the literature/studies; 4. Chart the data: and 5. Collate, summarize and report the results. In addition, The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses [16] checklist was reviewed to ensure there was a systematic approach to locating and managing the literature. Categorization of the peer roles and peer-led interventions identified in the literature (and occurring in step 4 and 5) was undertaken according to definitions documented by Ramchand et al. [17]. Ramchand et al. [17] undertook a systematic review of the literature of peer-supported interventions for health promotion and disease prevention. They then developed a consolidated typology of peer roles, type of intervention and intended outcomes. The categories identified are not specific to SCI, but can be extrapolated to the context of people with lived experience of SCI delivering formal and informal peer interactions. The authors of the current scoping review used categories of Ramchand et al. [17], reflecting and reporting on their applicability.

Research question

The research question guiding this review was as follows: what is the extent, range and nature of the research literature in the field of peer-led interventions for people following SCI?

Search for relevant literature

A search of the databases CINAHL Plus, Ovid MEDLINE and PsycINFO was undertaken. In addition, citation checks were conducted to identify other relevant articles. The search terms used were as follows: ‘spinal cord inj*’ OR ‘spinal cord les*’ OR ‘parapleg*’ OR ‘tetra’ AND ‘peer*’ OR ‘peer mentor’ OR ‘service user’. Searches were limited to articles published between 2000 and 2018 to identify the most contemporary literature in this rapidly evolving area and were written in English.

Select the literature

Inclusion criteria were as follows: the publication was an original research study (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods) of a peer-led intervention, with an evaluation component, and involved people with SCI over 18 years of age. Literature reviews and solely descriptive articles were excluded. The first author (LB) conducted the original database searches in consultation with the second author (GH). One hundred and thirty-two potentially relevant publications were located and exported to Endnote bibliographic software. Duplicates were manually removed by the first author leaving 75 articles. Titles and abstracts of these publications were uploaded to Microsoft Word for both authors to read and screen against the inclusion criteria. Following this, differences of opinion regarding inclusion or exclusion were discussed by the two authors, reducing the number to 36. The most common reason for exclusion of a publication was that the information related to peer-led interventions was incidental to the overall aim of the study and not described (n = 26). For example, Barclayet al. [6] investigated facilitators and barriers to social and community participation following SCI. Peer mentors were identified in their study as facilitators, but no detail regarding the specific role of the peers or the nature of the intervention were investigated or reported. Other articles excluded were either literature reviews (n = 7) or conference presentations, or periodicals (n = 7), which were not available or did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full texts of the remaining publications (n = 36) were reviewed against the inclusion criteria, leaving 21 articles for data extraction and charting Fig. 1.

Chart the data

The 21 selected articles were reviewed using a template developed by the two authors for this scoping review. The following key components were extracted and charted from the articles:

Authors; year and country of publication; aim(s) of study; study design; study participants (number of SCI participants); study outcomes; description of peer-led intervention; peer role (categories of best fit); description of peer training (if any); whether intervention was inpatient or community based; form of intervention (dyadic, group or combination of both); and duration of intervention.

Peer role definitions

The typology documented by Ramchand et al. [17] was used, as follows, to categorize the type of peer roles described in the publications reviewed:

-

1.

‘peer support’, informal and unstructured support to individuals such as providing reminders, encouragement or reinforcement, informal coaches and sharing personal experiences or narrative often as a ‘Buddy’ or partner in the intervention;

-

2.

‘peer counsellor’, provided knowledge, guidance and concrete tools to help individuals set/reach their health and wellness goals;

-

3.

‘peer facilitator’, responsible for facilitating group interactions (e.g., group discussions, team building activities) with the primary purpose of creating or strengthening relationships between and among individuals to help them set and reach goals together;

-

4.

‘peer educator’, delivered formal education or training on a specific topic, utilizing a protocolized curriculum and approach, and not involving a therapeutic relationship; and

-

5.

‘peer case manager’, helped others access or coordinated health and social services, including referring the participant to resources, or managing their activities within the intervention.

The first author categorized the roles based on the above typology, then the second author reviewed these, and where there was disagreement discussion occurred until agreement was reached.

Form of peer-led intervention

Peer interventions were characterized according to whether they occurred in a group context, dyadic (one to one) or a combination of both [17]. In addition, they were identified as one-off intervention, multiple or ongoing, and whether they were delivered as part of a clinical team.

Outcomes addressed by intervention

Data were extracted according to which outcome areas the intervention was aiming to address for people with SCI. Ramchand et al. [17] identified nine intervention outcome areas in their systematic review of peer-led interventions. Following consultation with a community-based SCI organization, this list was modified to include outcome areas most relevant to people with SCI. These were as follows: health self-management (prevention of secondary health conditions, physical fitness); health service usage (including hospital readmissions, visits to GPs); community integration (including social participation, social connectedness); employment outcomes; psychological outcomes (including depression, anxiety); engagement (self-efficacy, activation); knowledge about resources (funding information, travel, accessibility); and social welfare (housing, services).

Article quality was not assessed, as this was not relevant to the aim of categorizing the study in terms of study design, peer role, type of intervention and intended outcomes. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the research studies included and Table 2 provides a summary of the interventions.

Results

Article aims, design and participants

Of the 21 articles reviewed, there was significant heterogeneity in relation to the aims and design of the study, and the participants described. Eight of the studies reviewed were quantitative design, two of which were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in the United States [1, 2]. These studies had relatively large sample sizes with 158 and 84 participants, respectively. The interventions examined in the RCTs were also the focus of other studies that met the criteria for this scoping review [9, 10]. Other study types included two quasi-experimental designs [11, 18], a static two group comparison [4] and three prospective cross-sectional surveys [19,20,21]. The majority of the studies reviewed used qualitative methodologies (n = 11; 52%), with peer mentee samples ranging from 7 SCI participants [22] up to 15 SCI participants [3]. The qualitative studies not only examined the experience of the person receiving peer support intervention, but also described impacts for the ‘experienced’ mentor and elements of the peer interaction that were deemed beneficial.

Three studies had mixed diagnostic samples [23,24,25], whereas the remaining articles reported on interventions involving only people with SCI. Most of the study samples consisted of people who had received peer-led interventions (n = 19; 90%), whereas two included mixed samples of health professionals and organizations [19, 20]. The majority of interventions were undertaken in the United States (n = 12; 57%) and Canada (n = 4), with one study each in Norway, UK, Fiji and New Zealand.

Duration of intervention

As reported in Table 2 there was considerable variation in the duration of the peer-led interventions reported. Some interventions only lasted for 1 day [7], whereas others lasted for up to 1 year [19]. One study had no time limits [21]. Two studies provided minimal or no information regarding length of intervention [3, 25]. These were both qualitative studies, where the aim was to explore the participants’ experience with the peer-mentoring process or relationship.

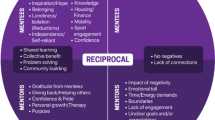

Peer roles and form of intervention

The most common peer role reported was that of peer supporter (n = 16; 76%), but this was often alongside additional roles such as educator, facilitator or counsellor, and most commonly in dyadic interactions. There was variation within these studies as to the description and detail provided of the intervention, at times complicating the categorization process. This however, reveals one of the advantages of utilizing peers in delivering interventions. Peers are able to simultaneously fulfil multiple roles, making their use in the workforce cost-effective and strengthening the credibility of them as a valued resource. This is particularly evident in the three articles that described and evaluated the My Care My Call intervention, a community-based telephone intervention for individuals with SCI, who used peer health coaches. The peers are described as acting as advisors, supports and role models [10]. Studies investigating residential peer-led programmes also outlined the peer taking on more than one role in group environments [24, 26], with peer support described alongside facilitator and educator. It is likely that the environment and structure of these programmes, involving both formal and informal interactions, capitalized on the value of using peers in this way.

Peer training

Description of the training that peers completed was reported in 14 articles (56%). Very detailed description was provided in several papers [5, 9, 11] or a description referred to in a supplemental paper [1, 10], or another article [27]. However, training was not referred to or discussed in seven of the studies. As was the case with description of the peer role, inconsistency and variation in reporting detail of the training delivered to the peer supporter limited the accuracy to which the peer role could be categorized.

Peer-led intervention characteristics and outcomes addressed by intervention

The majority of peer-led interventions were community based (n = 13; 62%) or both community and in-patient based (n = 5; 24%). This is consistent with the fact that the majority of interventions aimed to address community integration and social participation (n = 15; 71%), closely followed by health self-management (n = 10; 48%), all of which are community oriented goals. In addition, this also aligns with the location of peer mentors, as they were generally not paid employees of a hospital or health service where in-patient rehabilitation was undertaken, but rather worked or volunteered in community based organizations. Improving self-efficacy (n = 10; 48%) was the next most commonly addressed outcome addressed by intervention.

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to examine the extent, range and nature of the research literature evaluating peer-led interventions following SCI. Information was categorized according to study design, peer role, type of intervention and intended outcomes. In addition, the applicability of the peer-role categories in relation to their relevance for peer-led interventions following SCI were reviewed and will be discussed.

It is evident in literature published prior to the reviewed period of 2010 that, traditionally, intervention involving peers was valued, but largely considered a ‘feel good approach’. In recent years, the recognition of the potential contribution of people with lived experience of SCI has increased, which is reflected by the two RCTs included in this review. Overall, however, our review highlighted the limited number of recent studies that have rigorously investigated the efficacy of peer-led interventions following SCI.

Although a critical appraisal was beyond the scope of this study, of the research studies reviewed, a range of aims and designs were identified; there was a high level of variation in what was reported, most sample sizes were small, and qualitative methodology was most commonly used. Of the quantitative studies a range of tools were used to evaluate intervention outcomes, with little consistency between the studies. This demonstrates that although there is emerging evidence of the efficacy of peer-led interventions for people with SCI, such research is in its infancy. There have been calls for more rigorous, meaningful and generalizable research in this area [12]. For example, the use of longitudinal methodology would enable the potential efficacy of peer-led health interventions on improving self-management of secondary complications following SCI and the influence on other health and quality-of-life outcomes, to be examined. However, there are challenges in conducting such research that need to be recognized. People living with SCI are a relatively small population and recruiting people with SCI living in the community is challenging. One approach to address this challenge is to conduct studies across multiple regions or provinces such as has occurred in Canada through the Spinal Cord Injury Peer Mentorship Community University Research Group. This group represents SCI organizations and researchers across Canada, with the aim of developing a peer mentorship evaluation tool [28]. Another challenge is the ethical issue of making a service unavailable to some people, as is required in using an experimental design, for peer-led interventions that are already being provided by community organizations [4]. Such a design could only be utilized if a new service or programme is introduced to an experimental group, with specific and formalized guidelines for conducting the intervention, similar to the design adopted by Houlihan et al. [2, 10] in the My Care My Call programme and Gassaway et al. [18] in the provision of intensive peer mentoring vs. traditional peer support to newly admitted patients.

Ramchand et al. [17] consolidated typology of peer roles, type of intervention and intended outcomes were used to good effect in this scoping review. Although it provided a useful initial structure for categorization, there were some limitations in the application to the specific literature explored and also to the field of SCI in general. Limited description of the peer intervention provided in some of the studies reviewed made it challenging to accurately categorize the peer role. Furthermore, the typology description did not always match the role that the peer fulfilled (according to Ramchand’s definitions) [17]. When using this typology in the future to describe peer-led interventions for people with SCI, it may be useful to add an additional category between ‘peer support’ and ‘peer counsellor’. This additional category would relate to a role that provides more tailored input within a structured framework than the very informal nature of peer support. It may also include a situation where the peer has undertaken additional training, e.g., Motivational Interviewing, incorporated within their supporting role.

In relation to the intervention delivered, there was variation in the reporting of timing, duration and location of the peer intervention, who provided it and what training (if any) was involved. Yet, this level of detail is key to being able to replicate programmes and study designs, compare and contrast interventions, and ultimately develop an evidence base to strengthen service delivery. Divanoglou et al. [20] attempt to address this concern by documenting the components of ‘active rehabilitation’—a community peer-based approach—and exploring its characteristics and international variations. This work has made it more feasible to conduct future research that will explore the effectiveness of this particular community peer-based approach and provides a useful framework to guide other evaluation in the area of peer-led interventions [12].

The vast majority of studies were undertaken in the United States, which presents some challenges in generalizing to other jurisdictions such as Australia and Europe, with very different healthcare environments and different funding arrangements. Only one study reported on the delivery of peer support in a low-income country [24], yet there is broad recognition in the international literature of the utility and value of peer-led interventions in these communities [29, 30]. The lack of published research is likely related to the financial constraints within these countries. It is feasible that with increasing awareness in the literature of replicable programmes, together with further development of international collaboration, these limitations could be overcome.

By their very nature, peer-led interventions recognize the value of the lived experience. This review found limited programmes or studies that included people with SCI as equal or at least active partners in designing the intervention. People with SCI have called for their active involvement in setting the research agenda and being equal partners in research to ensure interventions are relevant and appropriate [31], and this is further substantiated by the existence of organizations such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute [32]. The Spinal Cord Injury Peer Mentorship Community University Research Group [28] provides a current working example of such an approach and one to be emulated. It is apparent, however, that more effort needs to be made by researchers to actively engage more equally with people with lived experience to design interventions and evaluations that are relevant and translatable.

It is now acknowledged that the incidence of non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction (NTSCD) is equal to or greater than that of traumatic SCI (TSCI) in developed countries [33, 34]. Yet, no studies identified in this review outlined interventions aimed specifically at addressing the needs of people with NTSCD. In addition, only three studies identified that they included people with both traumatic and non-traumatic aetiology in their sample [1, 4, 11]. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether people with NTSCD have been included in some of the other samples or whether the interventions have been designed only for people with TSCI. These results resonate with a study that explored the experiences of social and community participation of people with NTSCD, in which no participants reported receiving peer-mentoring assistance [35]. This adds to the evidence already known that people with NTSCD are often neglected in the traditional rehabilitation process [36].

Given the limitations of a scoping review, it is possible that some articles were missed. We attempted to address this by using a broad range of search terms and criteria to capture as many related articles as possible. It is also acknowledged that we did not undertake a formal appraisal of the quality of the articles included, but rather completed a descriptive analysis, which is consistent with scoping review methodology [13]. In addition, the guidelines for synthesizing literature in a scoping review remains unclear, particularly when reviewing studies with different designs [37].

In conclusion, this review provides important information regarding peer-led interventions for people with SCI. Significant variation in the literature was identified in relation to study design, description of the interventions and of peer training. A small number of studies were eligible for review, although increasingly with rigorous designs with clear frameworks. There were limitations in the research such as studies being predominantly conducted in developed countries and few peer-led interventions being described for people with NTSCD. However, there were emerging strengths such as the inclusion of people with lived experience of SCI in study design and implementation. Similarly, there was in-depth exploration of the nature of the peer mentor and mentee experiences, and the interaction between the two, offering rich insights to the potential value and credibility of the lived experience. This review made an initial attempt to categorize SCI peer-led interventions in relation to the role of the peer and the form of intervention. Further work is required to refine the typology used in order to facilitate replication of programmes and study designs. This, in turn, will enable interventions to be compared, thereby contributing to an evidence base that informs further service development and potentially strengthening the credibility of peers as a viable resource in in-patient and community settings.

References

Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman M, Hong M, Anziano P, DeVault K. Effects of peer mentoring on self-efficacy and hospital readmission after inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1526–34.

Houlihan BV, Brody M, Everhart-Skeels S, Pernigotti D, Burnett S, Zazula J, et al. Randomized trial of a peer-led, telephone-based empowerment intervention for persons with chronic spinal cord injury improves health self-management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1067–76.

Beauchamp MR, Scarlett LJ, Ruissen GR, Connelly CE, McBride CB, Casemore S, et al. Peer mentoring of adults with spinal cord injury: a transformational leadership perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1884–92.

Sweet SN, Michalovic E, Latimer-Cheung AE, Fortier M, Noreau L, Zelaya W, et al. Spinal cord injury peer mentorship: applying self-determination theory to explain quality of life and participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:468–76. e12.

Veith EM, Sherman JE, Pellino TA. Qualitative analysis of the peer-mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51:289–98.

Barclay L, McDonald R, Lentin P, Bourke-Taylor H. Facilitators and barriers to social and community participation following spinal cord injury. Aust Occup Ther J. 2016;63:19–28.

Latimer-Cheung A, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Brawley L, Gray C, Wilson A, Prapavessis H, et al. Developing physical activity interventions for adults with spinal cord injury. Part 2: motivational counseling and peer-mediated interventions, for people intending to be active. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:307–15.

Best KL, Miller WC, Huston G, Routhier F, Eng JJ. Pilot study of a peer-led wheelchair training program to improve self-efficacy using a manual wheelchair: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:37–44.

Skeels SE, Pernigotti D, Houlihan BV, Belliveau T, Brody M, Zazula J, et al. SCI peer health coach influence on self-management with peers: a qualitative analysis. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:1016–22.

Houlihan BV, Everhart-Skeels S, Gutnick D, Pernigotti D, Zazula J, Brody M, et al. Empowering adults with chronic spinal cord injury to prevent secondary conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1687–95. e5.

Ljungberg I, Kroll T, Libin A, Gordon S. Using peer mentoring for people with spinal cord injury to enhance self-efficacy beliefs and prevent medical complications. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:351–8.

Divanoglou A, Georgiou M. Perceived effectiveness and mechanisms of community peer-based programmes for Spinal Cord Injuries—a systematic review of qualitative findings. Spinal Cord. 2016;55:225.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

McKinstry C, Brown T, Gustafsson L. Scoping reviews in occupational therapy: the what, why, and how to. Aust Occup Ther J. 2014;61:58–66.

Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1386–400.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 2009. http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

Ramchand R, Ahluwalia SC, Xenakis L, Apaydin E, Raaen L, Grimm G. A systematic review of peer-supported interventions for health promotion and disease prevention. Prev Med. 2017;101:156–70.

Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman WM, Young T. Peer-led, transformative learning approaches increase classroom engagement in care self-management classes during inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42:338–46.

Balcazar FE, Hayes Kelly H, Keys CB, Balfanz-Vertiz K. Using peer mentoring to support the rehabilitation of individuals with violently acquired spinal cord injuries. J Appl Rehabil Couns. 2011;42:3–11.

Divanoglou A, Tasiemski T, Augutis M, Trok K. Active rehabilitation-a community peer-based approach for persons with spinal cord injury: international utilisation of key elements. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:545–52.

Shem K, Medel R, Wright J, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Duong T. Return to work and school: a model mentoring program for youth and young adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:544–8.

Jalovcic D, Pentland W. Accessing peers’ and health care experts’ wisdom: a telephone peer support program for women with SCI living in rural and remote areas. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury. Rehabilitation. 2009;15:59–74.

Ashton-Schaeffer C, Gibson HJ, Autry CE, Hanson CS. Meaning of sport to adults with physical disabilities: a disability sport camp experience. Sociol Sport J. 2001;18:95–114.

Chaffey L, Bigby C. ‘I Feel Free’: the experience of a peer education program with Fijians with spinal cord injury. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2018;30:175–88.

Haas BM, Price L, Freeman JA. Qualitative evaluation of a Community Peer Support Service for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:295–9.

Conway T. Exploration of the experiences and perceptions of spinal cord injured people who attend outdoor recreation programmes. [Thesis]. New Zealand: University of Otago, Dunedin; 2010.

Hernandez B. A voice in the chorus: perspectives of young men of color on their disabilities, identities, and peer-mentors. Disabil Soc. 2005;20:117–33.

McGill University. McGill Spinal Cord Injury Peer Mentorship Canada. 2017; https://www.mcgill.ca/scipm/research.

Ullah MM, Fossey E, Stuckey R. The meaning of work participation after spinal cord injury in Bangladesh. Spinal Cord. 2017;56:92–105.

Spinal Cord Society. Consumer Committee 2018. 2018; http://www.scs-isic.com/counseling_shivjeet.html.

Hammell KW. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation research: patient priorities, current deficiencies and potential directions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:1209–18.

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. 2019; https://www.pcori.org/.

Noreau L, Noonan VK, Cobb J, Leblond J, Dumont FS. Spinal cord injury community survey: a national, comprehensive study to portray the lives of canadians with spinal cord Injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20:249–64.

New P, Simmonds F, Stevemuer T. A population-based study comparing traumatic spinal cord injury and non-traumatic spinal cord injury using a national rehabilitation database. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:397–403.

Barclay L, Lentin P, Bourke-Taylor H, McDonald R. The experiences of social and community participation of people with non-traumatic spinal cord injury. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66:61–7.

Guilcher SJT, Craven BC, Lemieux-Charles L, Casciaro T, McColl MA, Jaglal SB. Secondary health conditions and spinal cord injury: an uphill battle in the journey of care. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:894–906.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–9.

Lucke KT, Lucke JF, Martinez H. Evaluation of a professional+ peer telephone intervention with spinal cord injured individuals following rehabilitation in South Texas. J Multicult Nurs Health (JMCNH). 2004;10:68–74.

Standal ØF, Jespersen E. Peers as resources for learning: a situated learning approach to adapted physical activity in rehabilitation. Adapt Phys Act Q. 2008;25:208–27.

Browning JH. Peer training as a cost-effective tool for SCI management in low-income countries. Paper presented at the International Spinal Cord Society Conference, New Delhi; 2010.

Kennedy P, Hindson L, Taylor N. Retrospective evaluation of residential activity courses for people with spinal cord injury. SCI Nursing. 2005; 22:72–8.

Hernandez B, Hayes EA, Balcazar FE, Keys CB. Responding to the needs of the underserved: a peer-mentor approach. SCI Psychosocial Process. 2001;14:142–9.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Transport Accident Commission for their support in conducting the scoping review.

Funding

This scoping review was supported by funding from the Transport Accident Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to designing and writing the review protocol, screening potentially eligible studies, extracting and analyzing data, interpreting results, updating reference lists and creating ‘Summary of findings’ tables. In addition, LB completed the database search.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statement of Ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations were followed during the course of this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barclay, L., Hilton, G.M. A scoping review of peer-led interventions following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 57, 626–635 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0297-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0297-x

This article is cited by

-

Knowledge translation gaps that need to be bridged to enhance life for people with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2024)

-

Outcomes of peer mentorship for people living with spinal cord injury: perspectives from members of Canadian community-based SCI organizations

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Understanding peer mentorship programs delivered by Canadian SCI community-based organizations: perspectives on mentors and organizational considerations

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

A comparative examination of models of service delivery intended to support community integration in the immediate period following inpatient rehabilitation for spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)