Abstract

Study design

Generic qualitative design.

Objectives

To explore how Chinese adults living with spinal cord injury (SCI) viewed the prospect of inpatient peer support programs within a rehabilitation setting.

Setting

Hospital in China.

Methods

A purposive sample of adult inpatients with SCI (N = 6) currently undergoing rehabilitation was recruited. Each participant was interviewed twice. Twelve interview transcripts were analyzed using a thematic method.

Results

Five higher-order themes were developed. First, participants had unique backgrounds and personal lives before and after their SCI and reported frustrations about their lives resulting from their SCI. Second, participants reported varying degrees of satisfaction with their rehabilitation and identified the facilitators and barriers to their rehabilitation. Third, their perspectives on peer support were shaped by their rehabilitation goals. For example, participants who solely focused on the recovery of physical functioning noted that peers could help to supplement existing rehabilitation programming by guiding their rehabilitation exercises. Participants who concentrated on their future lives believed peers could teach them new skills to facilitate their integration in the community. However, some participants felt they could not trust peers’ advice because peers are not healthcare providers. Fourth, peer support delivery options varied from online chat groups (i.e., WeChat), in-person conversations, and mentoring lectures. Finally, anticipated outcomes were related to obtaining practical and emotional support from peers, being motivated, and feeling understood.

Conclusions

Participants harbored mixed views on potential use-value and necessity of hospital-based peer support programs, which could inform future utilization of SCI peer support within Chinese hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peer support enables individuals to connect with others who share similar lived experiences. In a spinal cord injury (SCI) context, peer support recipients regard their peer as an ally whom they can trust and confide in about their challenges of living with SCI [1]. A peer who serves as a mentor can provide health information, reduce mentees’ distress and fear, and inspire mentees to develop a new identity as a person living with SCI [2]. In comparison with non-mentees, SCI peer mentees reported feeling more competent and connected with others. Higher competence and connection were then positively associated with participation in daily and social activities and quality of life [3]. Peer mentees also reported greater self-management, fewer rehospitalization, and increased self-efficacy after receiving peer mentorship [4, 5].

The majority of SCI peer support studies cited above have been conducted in a North American context. Other contexts, such as within a Chinese rehabilitation hospital, may differ greatly and thus additional testing is required [6]. The Chinese context may differ given the high incidence of SCI, estimated at 60,000 new cases each year [7]. Within Tianjin (where this study was conducted), incomplete paraplegia is the most common type of SCI (57.1%) and the frequency of incomplete SCI (74.8%) and paraplegia (67.8%) are higher than in North America, 66.7% and 57.8%, respectively [8, 9]. Further, Chinese adults with SCI typically report lower acceptance of their disability and higher levels of depression compared with those in Western societies. This difference was due to the lower perceived social support among Chinese adults with SCI [10]. Obtaining social support is particularly needed for Chinese adults to cope with their physical disabilities, which could be explained by the greater level of collectivism in Chinese culture than the Western [11]. As such, we may not be able to rely solely on peer support research conducted in Western society.

The need to adapt interventions to the specific contexts is emphasized in the ORBIT model. The model outlines a series of steps for adapting and implementing health and behavioral interventions, including conducting initial research to determine the need for interventions [6]. Despite studies examining peer support among non-SCI populations (e.g., diabetes) in China [12,13,14,15], little research has looked at the needs, feasibility, and acceptability of SCI peer support within a Chinese context. A position paper by Mei et al. suggested that Chinese research on peer support requires further exploration to shed light upon potential strengths and limitations [16]. In line with this position paper and the ORBIT model’s first phase, the purpose of this study was to explore how Chinese adults with SCI viewed the prospect of inpatient peer support programs within a rehabilitation setting. This study was guided by the following research questions: (1) What are the needs and perspectives on SCI peer support of Chinese adults with SCI? (2) How do they envision peer support programs could be delivered?

Methods

As per the Qualitative Research Level of Alignment Wheel [17], a generic qualitative design was used within a post-positivist inquiry paradigm. Within this paradigm, knowledge is produced in the most objective way possible [18, 19], but with some acknowledgement that the researchers’ values may inadvertently shape the interpretation of the results when adopting a modified objectivist epistemology [20]. ZS (principal researcher) conducted the recruitment and data collection by approaching participants at Tianjin Hospital to explore their views and needs for prospective SCI peer support programs in a Chinese rehabilitation context. ZS is a Chinese citizen with previous experiences of working alongside inpatients with SCI.

Participants

A purposive sampling method was used to recruit six Chinese adults with SCI at Tianjin Hospital. Tianjin Hospital is one of the largest hospitals characterized by orthopedics and rehabilitation medicine in northeast China. It receives clients with various medical conditions (e.g., joint replacement, fracture, and SCI). The length of stay of inpatients with SCI varies but commonly ranges between 6 months and 2 years at Tianjin Hospital. Participants of this study were recruited in the Rehabilitation Medicine Department of Tianjin Hospital. This department provides rehabilitation services including medication, daily physical and occupational therapy, and rehabilitation exercises. Eligible participants were required to be inpatients with SCI, currently undergoing rehabilitation, at least 4 weeks post-SCI, and able to communicate verbally. Six of eight recruited participants completed our study. All participants were men between the ages of 23 and 56 because no female inpatient with SCI was present at Tianjin Hospital during the recruitment (Table 1). None of the participants had been diagnosed with cognitive disorders. All participants were partially or fully covered by their work-related injury insurance.

Procedures

Ethics approval for this study was obtained prior to any recruitment. Participants consented to take part in two 30–60-min, audio-recorded, one-on-one, semi-structured interviews at a mutually agreeable time and location at Tianjin Hospital. Semi-structured interviews are suitable for an exploration of the perceptions and opinions of participants’ regarding complex issues [21]. They are flexible and allow the interviewer to adjust the interview to provide participants the opportunity to report their own feelings and perspectives [22]. To collect sufficient data with a relatively small sample, each participant was interviewed twice using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1). The first interview explored participants’ background and life experiences pre- and post-injury and built rapport between the researcher and participants. The second interview was conducted 2 weeks later and focused on participants’ needs for, and perspectives on, peer support. Participants may not have had a clear concept of peer support. The interviews started with broader questions (e.g., how do you think about your rehabilitation at this hospital) to allow participants to reflect on their daily interactions with other inpatients with SCI, which facilitated discussions on peer support.

Data analysis

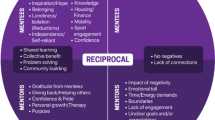

An abductive thematic analysis was used because it aligns with the generic qualitative design [17, 23]. ZS transcribed all 12 interviews verbatim in Chinese and analyzed the transcript with Nvivo 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd) by using a six-phase thematic analysis method [24]. Data were first deductively coded and categorized into higher-order themes that align with our research questions (i.e., perspectives on peer support and peer support delivery) and inductively coded into higher-order themes when the data were relevant but beyond our original research questions. The codes within each higher-order theme were then inductively categorized into subthemes (Fig. 1). ZS and a critical friend (SS, a North American SCI researcher) held ongoing discussions, totaling 12 h throughout the analysis, to ensure greater validity. The results were reviewed by QL (the fourth author) to ensure resonance with his experiences as a Chinese rehabilitation doctor. Participants’ quotes were translated from Chinese into English when writing the final report. Certain Chinese characters were kept and presented when the translation did not truly capture a common expression.

Results

Background and personal life

Participants living with their spouses and children (if any) described the value of their time spent with family before their SCI, while both single participants lacked this family connection because they left their hometown to seek employment (see Table 2). Despite the importance of family, participants highlighted that their jobs occupied a large portion of their lives before SCI. They reported having little time to participate in leisure activities, despite having great interest (see Table 2). This leisure need remained unmet after SCI due to the physical dysfunctions caused by SCI: “There have to be some changes [in my leisure activities]. I cannot do what I want to do now, such as fishing” (Zen). Further, their jobs were often high-risk or manual labor jobs (e.g., oil rig worker), which put them at an increased risk of injury, including SCI [25].

Participants’ relationships with their friends had not changed much since their SCI. They valued their friendship before SCI and highlighted how these friendships continued post-SCI as they had their close friends coming to visit them during their inpatient stay (see Table 2). However, participants expressed frustrations about their impaired physical functioning caused by SCI (see Table 2). According to participants, the recovery of their physical functioning had felt slower and harder as time went by: “The fastest [recovery] happened 1 month after my injury. From feeling hard to get off my bed to almost being able to walk. It was getting better day by day then; however, it is getting worse day by day now” (Qi). Some participants also reported developing negative emotions and moods during the inpatient stay. They felt down about the physical dysfunctions caused by SCI, which potentially affected their confidence and motivation to participate in rehabilitation (see Table 2).

Rehabilitation experiences

Participants discussed varied experiences in their rehabilitation and indicated having different goals and opinions about what helps and impedes their physical and/or psychological recovery.

Goals

Participants have approached their rehabilitation in different ways and with different goals of what rehabilitation can offer. Some participants focused solely on recovering from their SCI with the goal of re-establishing their physical functioning. By contrast, other participants set goals that focused more on their future life and saw rehabilitation as a way to facilitate their integration back to the community while living with SCI (see Table 2).

The most helpful component

Participants also had different opinions on the component that best helps them achieve their rehabilitation goals, which included the healthcare service provided by the hospital, family support, or their own effort (see Table 2).

Rehabilitation barriers

Despite seeing some benefits in their rehabilitation, certain rehabilitation barriers specific to the participants were identified, including lack of financial support, a need for improved healthcare service, and lack of detailed practical information during inpatient stay (see Table 2).

Interaction with others

Participants recalled whom they interacted with most often during their inpatient stay. The therapists and other inpatients appeared to be a good source of support for some participants (see Table 2).

Perspectives on peer support

As peer support programs have not been embedded in Tianjin Hospital, participants had no first-hand experience of structured peer support. However, informal support appears to exist because participants live or have lived alongside their peers. Therefore, participants shared their perspectives on peer support based on their previous experience.

Trust and distrust

Several participants indicated they would trust peers and their advice, and especially advice on how to effectively perform daily activities:

Interviewer: How much do you think you will trust a peer?

Lon: 60%.

Interviewer: Why?

Lon: I think sometimes they [peers] don’t have proper methods. Some methods they use are not as good as the ones my therapists taught me. For example, dressing and eating, they [peers] are not doing these well… Some of their [peers’] methods are too complicated and ineffective.

Interviewer: How about a peer who has good methods to eat and dress? How much will you trust him?

Lon: Probably 80%.

Interviewer: How come?

Lon: He knows those things because he should already return his life and he is experienced. In other words, those are parts of his current life. I have not re-entered my life [outside the hospital] so I don’t know how to live [with SCI]… If he’s someone whom I can see in-person, I will 100% trust him.

By contrast, some participants noted that they would not trust advice from peers because it did not come from qualified healthcare providers: “I trust doctors more than peers for sure because doctors are professional” (Qiang).

Ideal peer

Several participants believed that an ideal peer would have similar injuries, health conditions, and functioning status: “[If] they are two individuals with similar injuries, they will have common topics to discuss because they would take the same medicine and therapy. It would be easier for them to talk to each other” (Feng). Similarly, some participants would feel difficult to relate to a peer who is coping with a very different situation (See Table 2). However, other participants would interact with someone with prolonged and successful experiences of living with SCI so that they could ask him/her questions about the recovery process:

Feng: If I know someone who has more experience [with coping with SCI], I will try to know him. I will ask him “How do you think about my walking [performance]? If it’s wrong, what is wrong?” He will point it out [一针见血].

Different focuses

Some participants noted that having different focuses could be a potential challenge for peers to help each other. For example, some participants heavily focused on the recovery of physical functioning; while others preferred to concentrate on life outside of rehabilitation (e.g., returning work). One participant engaged in informal peer support through an online chat group. However, he felt the topics discussed in the chat group were often irrelevant because he was mostly concerned with how to live independently after discharge, rather than information on medical issues:

Lon: Some of them talk about complications, such as spasm. A lot of people told this guy what he should do. There were too many different ways. However, I don’t care about that [because I don’t have spasm]. They never talk about how to live independently in the future. I seldom look at it [chat] because it’s [the topics] often irrelevant to me.

Peer support delivery

Participants discussed how they envisioned peer support could be delivered during their inpatient stay and expressed their concerns about its feasibility.

Online vs. in-person

Some participants favored peer support to be delivered through online approaches, which were deemed popular and accessible: “WeChat [a Chinese social media] is popular. For example, I can send a video about how I do rehab exercise to the group [on WeChat]” (Lon). Online approaches were favored also because meeting a peer in-person may make them feel self-conscious about their potential inferior physical function:

Wei: In some situations, not meeting in-person will have less [psychological] impact. For example, he shows me his medical records that he had a worse injury than me; however, he is standing in front of me right now. I am still far away from that [standing] so I would feel very stressed.

Other participants favored peer support to be delivered in-person, such as a need for in-person communication with a peer mentor:

Feng: If I have a chance to meet him [a peer mentor] in-person, I will ask a lot of questions like “How did you achieve that?”. If you tell me where this guy [peer mentor] is or his phone number, I will call him right away. [I will ask him] “Shall we meet up when you have time?”, “Shall we meet for lunch or dinner?”, or “Can you guide me a bit?”. That will be great if he is willing to help… The hospital should invite him to give a talk if possible.

One-on-one vs. multiple peers

Some participants preferred a one-on-one relationship because they speculated that the support (e.g., health information sharing) could be individualized and they would feel more comfortable talking about their health issues to only one peer. By contrast, some participants craved connections with multiple peers to learn ideas/tricks (e.g., wheelchair transfer methods) from different resources: “I like to have a group consisting of five or six people. We will have more meaningful conversations” (Lon). However, participants cautioned that having too large of a peer group may impede conversations and enhance their personal insecurities (See Table 2).

Frequency

Participants mentioned that the frequency of peer interactions should be scheduled according to their rehabilitation progress:

Wei: I think the frequency will be like a couple of months. After I make some progress, we can talk about what the next step is. It’s step by step. It could be 3 months or even more. The recovery of SCI is measured by month, even years.

Feasibility concerns

Participants forecasted certain challenges associated with the feasibility of implementing inpatient peer support programs. First, they noted that hosting peer-led programs would increase the workload for hospital administrators. Second, the costs of inpatient healthcare services have already caused a financial burden for participants. They felt they would be unable to afford future peer support programs personally. Third, several participants were concerned that their physical disability would limit their access to and participation in peer support (e.g., distance).

Anticipated outcomes

Motivation

Some participants believed a peer mentor could motivate their engagement in rehabilitation: “If I see someone transferring from bed to wheelchair by himself, I will be aware that it’s something I have to know too. Then I will practice it” (Lon). Participants could see that peer as a role model and try to achieve the role model’s functioning level.

Understanding

Some participants felt they could be better understood by peers who were also living with SCI. They believed conversations among peers would be more open, honest, and occur with less misunderstandings than speaking with non-peers: “I am sure that he [peer] can understand me because he went through the same thing as me.” (Wei)

Information sharing

Some participants highlighted the potential role of peers from a practical standpoint. They expected peers could share health information (e.g., complications prevention, effective rehabilitation exercise, and ways to conduct daily activities), as well as teach strategies to live independently with SCI after leaving the hospital.

Emotional support

Several participants regarded peers as a resource of emotional support. They felt that talking to a peer would help “release mental stress” and afford them a source of encouragement and hope:

Lon: They [peer mentors] will give you some hope and let you know that the future is fine. For example, if someone who returned home tells you, “Life is not as hard as you think. It’s simple”, I will listen to him because he has already entered his life [outside of rehabilitation].

Better communication with health professionals

Several participants suggested peers could help them better understand the language of health professionals: “[For example,] The doctors tell me how to do a new exercise. I probably don’t understand him right away. A peer who understands how to do this exercise can translate the doctor’s language for me so that I could get it” (Feng).

Discussion

Our results helped obtain an understanding of how Chinese adults with SCI see the potential role of peers within a culturally distinct rehabilitation context. Similar to the findings discovered among the North American SCI population [8], we identified an unmet need for peer support and specified that Chinese adults with SCI need to obtain practical information, emotional support, and motivation from peers. These needs closely aligned with the three main outcomes of hospital-based SCI peer mentorship identified by Veith et al. [2], which is promising for the development of Chinese peer support programs.

In existing Chinese peer support interventions for non-SCI populations [12,13,14,15], much emphasis is placed on selecting peer mentors who have sufficient coping experience. However, an ideal peer for Chinese adults with SCI may not solely be an experienced peer. Characteristics of ideal peers mentioned by our participants aligned with high-quality peer mentorship characteristics such as “optimistic”, “there for mentee”, and “role model”, but not all (e.g., nonjudgmental) [26]. Having trust in peers was addressed by our participants as an essential characteristic of an ideal peer, which was consistent with the “highly credible” [2] and “trustworthy” [26] characteristics identified in previous research. However, having similar injuries and functioning status appears to be particularly important for Chinese adults with SCI to select their ideal peer, which is different from findings in Western contexts [26]. These findings highlight the importance of conducting contextually specific qualitative studies, as suggested by the ORBIT model [6].

Based on the feasibility challenges identified in our study, we cannot assume that most Chinese rehabilitation hospitals would be capable of hosting and funding inpatient peer support programs. In fact, through conversations with healthcare providers and a search of websites of major Chinese hospitals, we found no indication of existing hospital-based SCI peer support programs in China. It may point out a need for such programs or a lack of knowledge and resources to build these programs. However, our study found that informal peer interactions among inpatients with SCI may exist. Informal interactions may offer an important starting point to deliver structured peer support programs within Chinese hospitals. Several peer support programs exist in Canada and are primarily led by provincial nongovernmental SCI organizations (e.g., SCI British Columbia). These organizations provide peer support services for people with SCI within the rehabilitation and community settings [27, 28]. Similarly, local SCI organizations in China could be a potential resource for the future provision of peer support programs in collaboration with rehabilitation hospitals.

Practical implications

Our findings suggested that Chinese rehabilitation hospitals should first consider encouraging and promoting informal interactions among inpatients with SCI as a starting point to develop peer support programs. In collaboration with local SCI organizations, hospitals could deliver structured peer support by Internet as an economical and accessible option. For example, online peer resources (e.g., WeChat group) have been found cost effective for people with diabetes [29]. Due to its lack of institution-based credibility, there are concerns on utilizing WeChat in healthcare [30]. Peer mentorship programs in Chinese rehabilitation hospitals may also require linking peer mentors with health professionals to help build a trusting relationship between mentors and mentees, as participants reported high levels of trust in health professionals. This connection could help peer mentors increase their medical knowledge of SCI while also facilitating mentees’ communication with health professionals. The implementation of these ideas would also need to be adapted based on the cultural and social differences within regions in China, whether online or in Chinese rehabilitation hospitals, such as Tianjin Hospital.

Study limitations

All six participants were male, resulting in a lack of insights from Chinese women living with SCI. Although women occupied a relatively small proportion (~15%) of the Chinese SCI population [9], future research needs to understand the potential gender discrepancies among the SCI population in China and see how it differs from our findings. Second, all participants were from northeast China, which may represent a different experience than individuals in other parts of China. Third, the quotes presented in our results were translated from Chinese to English, thus some original meanings may have been altered, which leads to a call for future studies presenting the original data in Chinese. Finally, this study remains an exploratory qualitative study as the preliminary phase prior to the implementation of peer support programs. It however provides new and potentially useful insights into how Chinese inpatients view prospective peer support programs within a rehabilitation context. We may also need to conduct research with hospital staff to understand the facilitators and/or constraints to delivering SCI peer support. Healthcare providers, settings, and countries could reflect on the similarities between their contexts and Tianjin Hospital in order to develop their own SCI peer support programs.

Conclusions

Participants in this study harbored mixed views on the potential use-value and necessity of hospital-based peer support programs in China. Participants’ insights further advanced our understandings of how peer support could potentially operate and be effectively delivered within a Chinese hospital-based rehabilitation setting. Our results could inform future studies on designing and testing SCI peer support programs, which aim to examine if peer support is a viable rehabilitation option among Chinese SCI population.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Pentland W, Walker J, Minnes P, Tremblay M, Brouwer B, Gould M. Women with spinal cord injury and the impact of aging. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:374–87.

Veith EM, Sherman JE, Pellino TA, Yasui NY. Qualitative analysis of the peer-mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51:289–98.

Sweet SN, Michalovic E, Latimer-Cheung AE, Fortier M, Noreau L, Zelaya W, et al. Spinal cord injury peer mentorship: applying self-determination theory to explain quality of life and participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:468–76.

Gassaway J, Jones ML, Sweatman WM, Young T. Peer-led, transformative learning approaches increase classroom engagement in care self-management classes during inpatient rehabilitation of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42:338–46.

Houlihan BV, Brody M, Everhart-Skeels S, Pernigotti D, Burnett S, Zazula J, et al. Randomized trial of a peer-led, telephone-based empowerment intervention for persons with chronic spinal cord injury improves health self-management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1067–76.

Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, Naar-King S, Reynolds KD, Hunter CM, et al. From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015;34:971–82.

Qiu J. China spinal cord injury network: changes from within. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:606–7.

Noreau L, Noonan V, Cobb J, Leblond J, Dumont F. Spinal cord injury community survey: a national, comprehensive study to portray the lives of Canadians with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20:249–64.

Ning GZ, Yu TQ, Feng SQ, Zhou XH, Ban DX, Liu Y, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in Tianjin, China. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:386–90.

Jiao J, Heyne MM, Lam CS. Acceptance of disability among Chinese individuals with spinal cord injuries: the effects of social support and depression. Psychology. 2012;3:775–81.

Triandis HC, Bontempo R, Betancourt H, Bond M, Leung K, Brenes A, et al. The measurement of the etic aspects of individualism and collectivism across cultures. Aust J Psychol. 1986;38:257–67.

Chen HE, Zheng YH, Yan P. Bingyou zhichi tuandui zai gaibian chuzhen 2 xing tangniaobing huanzhen shenghuo fangshi zhong de zuoyong [The role of peer support team in changing the lifestyle of newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes]. J Nurses Train. 2013;28:461–3. In Chinese.

Gui YH, Wang XX. Bingyou zhichi tuandui dui manxing zusexing feijibing huanzhe zhiliao yicongxing de yingxiang [The effect of peer support team on treatment compliance of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]. China Mod Dr. 2015;53:128–30. In Chinese.

Qiu JJ, Hu Y, Huang JL, Lu ZQ. Ruxianai kangfu huzhu zhiyuanzhe bingyou zhichi fangshi de yingyong ji xiaoguo [The application and effect of mutual voluntary peer support on the rehabilitation of patients with breast cancer]. Chin J Nurs. 2008;43:690–3. In Chinese.

Wang L, Zhu XL, Ren H, Jia XH, Wang XL. Bingyou tuandui zhichi dui naochuzhong piantan huanzhe fuxing qingxu ji fangfu duanlian yicongxing de yingxiang [The effect of peer support team on the negative emotions and rehabilitation exercise compliance of stroke patients with hemiplegia]. J Int Psychiatry. 2017;44:1111–3. In Chinese.

Mei YX, Zhang ZX, Li YS. Meiguo tongban zhichi zhuanjia fazhan de xiankuang ji dui woguo de qishi [The Development of Peer Support Specialist in U.S. and Its Implications in China]. Medicine &. Philosophy 2017;38:46–47. In Chinese.

Bradbury-Jones C, Breckenridge J, Clark MT, Herber OR, Wagstaff C, Taylor J. The state of qualitative research in health and social science literature: a focused mapping review and synthesis. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20:627–45.

Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handb Qual Res. 1994;2:105–17.

Lincoln YS, Lynham SA, Guba EG. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. Sage Handb Qual Res. 2011;4:97–128.

Ponterotto JG. Qualitative research in counseling psychology: a primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. J Couns Psychol. 2005;52:126–36.

Barriball KL, While A. Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: a discussion paper. J Adv Nurs-Inst Subscr. 1994;19:328–35.

Sparkes AC, Smith B. Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: from process to product. United Kingdom: Routledge; 2013.

Samuels WJ. Signs, pragmatism, and abduction: the tragedy, irony, and promise of Charles Sanders Peirce. J Econ Issues. 2000;34:207–17.

Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis (Routledge). 2016:213–27.

Shao ZG, Zhang SB. Zhongguo anquan shengchan shigu de shikong fenbu ji fengxian feixi [Spatiotemporal Distribution and Risk Analysis of Safety Production Accidents in China]. China Public Secur. 2016;4:14–20. In Chinese.

Gainforth HL, Giroux EE, Shaw RB, Casemore S, Clarke TY, McBride CB, et al. Investigating characteristics of quality peer mentors with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:1916–23.

Beauchamp MR, Scarlett LJ, Ruissen GR, Connelly CE, McBride CB, Casemore S, et al. Peer mentoring of adults with spinal cord injury: a transformational leadership perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1884–92.

Shaw RB, McBride CB, Casemore S, Martin Ginis KA. Transformational mentoring: leadership behaviors of spinal cord injury peer mentors. Rehabil Psychol. 2018;63:131.

Xie B, Ye XL, Sun ZL, Jia M, Jin H, Ju CP, et al. Peer support for patients with type 2 diabetes in rural communities of China: protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:747.

Jin XL, Feng H, Zhou Z. Understanding Healthcare Knowledge Diffusion in WeChat. In: Wuhan International Conference on e-Business. Wuhan: Association For Information Systems; 2017.

Acknowledgements

Data collection of this project was assisted by Tianjin Hospital, China. Each named author has substantially contributed to conducting the underlying research and drafting this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZS was responsible for designing the study, conducting the data collection and analysis, interpreting results, and writing the paper. JK and LS was responsible for assisting the study design and paper writing. QL and LCW contributed to recruiting the participants and providing the research setting. SS was the supervisor of the corresponding author (ZS) and contributed to analyzing data, interpreting results, and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board-II of McGill University and also from the Research Ethics Board of Tianjin Hospital. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Koch, J., Schaefer, L. et al. Exploring how Chinese adults living with spinal cord injury viewed the prospect of inpatient peer support programs within a hospital-based rehabilitation setting. Spinal Cord 58, 1206–1215 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0490-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0490-y