Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown that Black men receive worse prostate cancer care than White men. This has not been explored in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) in the current treatment era.

Methods

We evaluated treatment intensification (TI) and overall survival (OS) in Medicare (2015–2018) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA; 2015–2019) patients with mCSPC, classifying first-line mCSPC treatment as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) + novel hormonal therapy; ADT + docetaxel; ADT + first-generation nonsteroidal antiandrogen; or ADT alone.

Results

We analyzed 2226 Black and 16,071 White Medicare, and 1020 Black and 2364 White VHA patients. TI was significantly lower for Black vs White Medicare patients overall (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.58–0.81) and without Medicaid (adjusted OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.57–0.87). Medicaid patients had less TI irrespective of race. OS was worse for Black vs White Medicare patients overall (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.20; 95% CI 1.09–1.31) and without Medicaid (adjusted HR 1.13; 95% CI 1.01–1.27). OS was worse in Medicaid vs without Medicaid, with no significant OS difference between races. TI was significantly lower for Black vs White VHA patients (adjusted OR 0.75; 95% CI 0.61–0.92), with no significant OS difference between races.

Conclusions

Guideline-recommended TI was low for all patients with mCSPC, with less TI in Black patients in both Medicare and the VHA. Black race was associated with worse OS in Medicare but not the VHA. Medicaid patients had less TI and worse OS than those without Medicaid, suggesting poverty and race are associated with care and outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The treatment landscape for metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) has rapidly evolved. Treatment intensification (TI) with docetaxel, novel hormonal therapy (NHT; abiraterone, apalutamide, enzalutamide), or both, added to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has substantially improved survival [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and is a consensus guideline recommendation [10,11,12,13]. However, TI is underutilized in favor of ADT alone or with first-generation nonsteroidal anti-androgen (NSAA) [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], despite guidelines recommending first-generation NSAAs only to block testosterone flare [11, 13]. Reasons are not well understood but may include disease characteristics or comorbidities, cost or access issues, practice pattern inertia, ignorance of current data, or safety and tolerability perceptions [22].

Previous studies found that Black men are more likely to receive inadequate prostate cancer (PC) care than White men [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]; however, this has not been explored during the NHT era for mCSPC. This is particularly concerning because Black men have higher PC mortality and are more likely to develop aggressive disease at a younger age [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. While the latter may be due to biologic or genetic factors [38, 39], the former is driven in part by factors affecting access to care [40,41,42,43], partly resulting from systemic racism. In clinical trials, there are often too few Black patients to analyze outcomes by race or race is not reported at all [44]. As we progress further into the NHT era, we hypothesize that the disparities evident in the treatment and survival of Black men, compared with White men with mCSPC, remain.

Real-world data are vital to understanding racial disparities in mCSPC. We evaluated potential disparities in the treatment and survival of men with mCSPC in the USA. We used two large, nationally representative USA claims databases with different treatment settings and payer structures: Medicare, which includes supplemental plan options and dual enrollment with Medicaid for low-income patients, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a single-payer, equal-access, closed system. This is the first large study of racial disparities in treatment, survival, and associated factors, including access to care and poverty, in mCSPC during the NHT era.

Methods

Data sources

Data were collected from a 100% sample of Medicare Fee-For-Service beneficiaries (January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018) from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (January 1, 2015 to June 22, 2019). Medicare data contain patient demographics, enrollment, and claims history (including drug, diagnosis, physician visits, procedures [Medicare Part A, B, D]). Death dates were verified against US Social Security Administration agency or Railroad Retirement Board records. VHA data comprise electronic records from the largest integrated healthcare system in the USA with approximately 1300 care sites serving >9 million veterans and their dependents annually [45], and contain patient demographics, enrollment, and clinical information (e.g., inpatient and outpatient pharmacy data, laboratory tests, hospitalizations, outpatient visits). Death dates were verified through VHA facilities, death certificates, and the National Cemetery Administration. Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption was obtained from the New England IRB (Medicare) and from Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System IRB (VHA).

Study cohort

Unless specified, the same sample selection criteria were applied to Medicare and VHA patients with metastatic PC to select mCSPC patients (Supplementary Fig. S1). Patients had ≥1 medical claim with a diagnosis code for PC and ≥1 claim for metastasis on or after the first observed PC diagnosis. Patients received ADT (surgical or medical castration) <90 days prior to or any time after the first observed metastasis diagnosis.

The first ADT initiation date meeting these requirements was defined as the index date. Adult Black, non-Hispanic, and White males at index with continuous enrollment ≥365 days before (baseline period) and ≥120 days after index were included. Follow-up was from index to end of continuous enrollment, data availability, or death, whichever occurred first.

Exclusion criteria are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1; because treatment options for mCSPC have changed substantially since 2014 (with the introduction of docetaxel and NHT), we excluded patients with index dates before 2015. Patients with missing race information and VHA patients with missing prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurements <120 days before index were excluded. PSA information is unavailable in Medicare. Included patients were classified into Black and White groups based on information reported during index year (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Patient characteristics and study outcomes

Demographics, baseline disease characteristics, treatment history, and baseline comorbidities (modified Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI; excluding cancer] and relevant individual comorbidities) [46, 47] were assessed. First-line mCSPC treatment was defined as treatment received <30 days before and <120 days after index (index window) and classified into ADT + NHT, ADT + docetaxel, ADT + first-generation NSAA, and ADT alone. NSAA use was required for ≥90 days to avoid capturing short-term use for testosterone flare. Patients who received NHT or docetaxel and NSAA were categorized into ADT + NHT or ADT + docetaxel groups. Patients who received both NHT and docetaxel during the index window were categorized based on the drug received first.

TI was defined as receiving ADT + docetaxel or ADT + NHT as first-line mCSPC treatment. Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from index to death. Patients alive at the end of continuous eligibility or data availability were censored.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted by race in Medicare and VHA data separately. Summary statistics were reported for continuous variables. Counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were calculated for unadjusted comparisons of baseline characteristics. SMDs >10% were considered statistically significant [48,49,50].

The proportion of Black and White patients who received ADT + NHT, ADT + docetaxel, ADT + NSAA, and ADT alone annually was determined. Unadjusted and adjusted generalized linear models (GLMs) with binomial distribution and logit link estimated the odds ratio (OR) of TI. Adjusted models accounted for baseline demographics, disease characteristics, treatment history, and comorbidities and were selected based on clinical input and SMD > 10%. In the Medicare analysis, a second adjusted model accounted for dual Medicaid enrollment. Medicaid enrollment was recorded based on income and assets; from 2015 to 2020, the median income eligibility limit was 138% of the Federal Poverty Level [51]. For the VHA, a second adjusted model accounted for median household income per zip code (patient-level data were unavailable). For sensitivity analyses, VHA models accounted for baseline laboratory values (i.e., PSA, hemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase) and education attainment (i.e., percentage of population in a zip code age ≥25, with a bachelor’s degree or higher).

Kaplan–Meier analyses assessed OS. Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards (PH) models estimated the hazard ratio (HR). Adjusted Cox PH models accounted for the same variables used in the GLMs for TI.

Results

Patient population

Overall, 2226 (12.2%) Black and 16,071 (87.8%) White patients were included in the Medicare analysis; 12.8% were also Medicaid-enrolled; 40.3% of Black and 9.0% of White patients in Medicare were Medicaid-enrolled. The VHA analysis included 1020 (30.1%) Black and 2364 (69.9%) White patients (Table 1). Black patients were younger than White patients (mean age, Medicare: 73.9 vs 76.9 years, SMD –38.3%; VHA: 70.1 vs 74.4 years, SMD –45.2%). A higher proportion of Black vs White patients resided in the South (Medicare: 55.0% vs 33.5%, SMD 44.4%; VHA: 38.5% vs 29.4%, SMD 19.3%). Proportions of Black and White patients with visceral metastasis or on pain medication at baseline were similar. In the VHA, more Black vs White patients had visceral metastasis (12.5% vs 8.7%, SMD 12.6%) and pain medication use (75.1% vs 62.2%; SMD 28.0%). Black patients had a higher mean modified CCI score vs White patients in both datasets. In the VHA, Black patients had a higher median PSA (40.5 vs 23.6; Supplementary Table S1), lower median hemoglobin (12.4 vs 13.3), and similar median alkaline phosphatase measurements vs White patients.

Treatment intensification

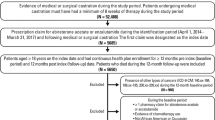

The proportion of patients receiving TI as first-line mCSPC treatment increased slowly over time (Fig. 1): Medicare, from 5.9% in 2015 to 11.9% in 2018 for Black patients and from 6.8% to 17.3% for White patients; VHA, from 9.7% in 2015 to 28.0% in 2019 for Black patients and from 8.9% to 29.8% for White patients. However, TI was overall underutilized (Medicare: 10.3%; VHA: 19.9%). Even in 2018 and 2019, the most recent years of data available, more than two-thirds of patients did not receive upfront NHT or docetaxel, across both races.

A First-line treatment for mCSPC over time by race in Medicare. B First-line treatment for mCSPC over time by race in the VHA. ADT androgen deprivation therapy, mCSPC metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, NHT novel hormonal therapy, NSAA nonsteroidal antiandrogen, VHA Veterans Health Administration.

For Medicare, the unadjusted odds of Black patients receiving TI was 21% lower vs White patients (Table 2; unadjusted OR 0.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.92, p = 0.003; adjusted OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.58–0.81, p < 0.001). Among patients without Medicaid enrollment, adjusted odds were 30% lower for Black vs White patients (adjusted OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.57–0.87, p = 0.001). Among patients with Medicaid enrollment, there was no significant difference in TI between races. Overall, Medicaid-enrolled patients were less likely to receive TI compared with those not Medicaid-enrolled (Table 3; adjusted OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.57–0.80, p < 0.001; Supplementary Fig. S2).

For the VHA, the unadjusted odds of Black patients receiving TI was not statistically significant (Table 2). After adjusting for patient characteristics, a statistically significant 25% lower TI rate among Black patients was observed (adjusted OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61–0.92, p = 0.006; additionally accounting for median household income per zip code also showed a difference: OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63–0.95, p = 0.016). Sensitivity analyses showed similar results (Supplementary Table S2). The distribution of subsequent treatment was similar between Black and White patients in both datasets (Supplementary Table S3).

Overall survival

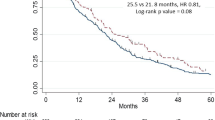

In Medicare, mean ± SD (median) follow-up was 18.5 ± 11.3 (15.9) months for Black patients and 20.0 ± 11.5 (17.8) months for White patients. Median OS (95% CI) was 44.2 (38.5–not reached [NR]) months for Black patients and NR for White patients. Black patients had a 26% higher unadjusted risk of death vs White patients (Fig. 2; Table 2; HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.16–1.37, p < 0.001), and a 20% higher risk of death after adjusting for baseline patient and cancer characteristics (Table 2; HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.09–1.31, p < 0.001). In models adding Medicaid enrollment, Black patients had a 13% greater risk of death vs White patients among patients without Medicaid enrollment after adjusting for baseline characteristics (Table 2; Supplementary Fig. S3; median OS 45.5 months vs NR in Black vs White patients, adjusted HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01–1.27, p = 0.037). Among Medicaid-enrolled patients, there was no significant racial difference in OS after adjustments.

However, Medicaid-enrolled patients, regardless of race, had worse OS than patients of the same race who were not Medicaid-enrolled (Table 3; HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.37–1.63, p < 0.001 for all patients; HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.31–1.69, p < 0.001, and HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.42–1.74, p < 0.001 for Black and White patients, respectively).

For the VHA, mean ± SD (median) follow-up was similar for both races: 24.9 ± 15.3 (Black: 21.2; White: 21.4) months. Median OS (95% CI) was 43.6 (38.1–50.3) months for Black patients and 42.2 (39.7–45.5) months for White patients. There was no statistically significant difference in OS between Black and White patients, with or without adjusting for patient characteristics (Fig. 2; Table 2; Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

The treatment landscape in mCSPC has changed markedly in recent years [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Our study is the first to specifically assess emerging racial disparities in TI and OS in mCSPC in the USA, using two large national databases. Given the databases and study size, these results are likely generalizable to patients with mCSPC receiving active treatment in the USA. Moreover, several TI options were available on formulary at the first dates of data collection.

We observed an initial underutilization of TI among the overall population of mCSPC patients, which was more pronounced among Black vs White patients in both Medicare and the VHA. Underutilization of upfront TI is consistent with other reports [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Our study suggested that underutilization of TI persisted for up to 4 years following the introduction of docetaxel in 2015 and up to 2 years after the introduction of abiraterone in 2017 as life-prolonging therapies for mCSPC. While individual assessment of risk tolerance and goals of care should ultimately determine whether TI is appropriate, these data may signal that urgent action is needed to make mCSPC treatment more guideline-adherent.

Adding to the urgency, Black patients were less likely to receive TI vs White patients after adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics. Less TI for Black vs White patients in Medicare was most evident in patients without Medicaid enrollment (30% less likely for Black patients; Table 2). The racial difference in Medicare patients with Medicaid was not significant (Table 2). For both races, the use of TI was lower among Medicaid-enrolled vs patients who were not Medicaid-enrolled (20% and 37% lower in Black and in White patients, respectively; Table 3), suggesting that economic status affects the use of TI in conjunction with race. The VHA data used for the primary analysis did not contain a variable directly reflecting individual patients’ economic status. However, adjusting for median regional household income and education based on zip code had minimal impact on the racial disparity in TI. This suggests that the economic factors influencing treatment may be mitigated in the VHA, perhaps because of its more uniform benefits design.

In addition, worse OS was observed in Black patients compared with White patients in Medicare overall, as well as among patients without Medicaid enrollment. This disparity in OS was not observed for low economic status or within the VHA, suggesting a potential benefit of a single-payer system with limited out-of-pocket expenses. In the Medicare population, since a greater proportion of Black patients were Medicaid-enrolled vs White patients (40.3% vs 9.0%), the lower OS for Black patients may be at least partially driven by associations with the care of Medicaid-enrolled patients. Indeed, Medicaid-enrolled patients had worse OS compared with patients not enrolled in Medicaid in both races (HR 1.49 for Black patients and 1.57 for White patients, both p < 0.001; Table 3), suggesting that poverty, in addition to Black race, is associated with worse OS.

Racial disparities in PC treatment have been demonstrated in prior studies among patients with localized PC or mCRPC [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]; however, none have examined disparity among patients with mCSPC during the current NHT era. Our study indicates that racial disparity exists in mCSPC and the number of patients potentially impacted suggests that this is a more extensive problem in mCSPC. Such disparity in Medicare might be partially caused by differences in drug access across races in prescription benefit designs. However, even in a system with a more standardized prescription plan (an equal-access healthcare system, e.g., the VHA), TI disparity by race still exists. The racial disparity of TI in the VHA (25% less likely for Black patients) was in between that observed among Medicare patients with and without Medicaid enrollment. This might be related to physicians’ prescribing habits, and patients’ and physicians’ ability to navigate barriers to obtaining TI, or in some cases patient reluctance.

Previous studies have demonstrated that racial disparities exist in PC outcomes, with Black men experiencing higher mortality rates compared with White men [52]. However, growing evidence suggests that given equal treatment, outcomes may be better for Black than White men with late-stage PC [20, 53,54,55,56,57,58]. There are limited, inconclusive data on potential differences by race in response to guideline-recommended mCSPC treatment [59,60,61]. Our findings suggest caution in ruling out racial disparity in either treatment or outcome. While we found that race did not have a significant impact on OS in mCSPC under a system with relatively equal access to care (the VHA) and among the economically disadvantaged (Medicare with Medicaid enrollment), it is not entirely clear if this represents an extension of the findings from the studies examining early disease [40, 42, 59] to mCSPC, or more troublingly, a dampening down of the OS advantage for Black patients in mCRPC studies [53,54,55, 57], where treatment disparities between races were not as apparent. Moreover, worse OS for Black vs White patients is still observed in the larger subgroup (Medicare without Medicaid enrollment).

Given that we are still early in the era of upfront NHT for mCSPC, future research should elucidate whether racial differences exist in response to TI and, ultimately, patient outcomes. Notably, median OS in our study was around 42 months, coinciding with the ADT-alone arm in CHAARTED [1], LATITUDE [3], TITAN [8], and ARASENS [9] (OS, 36.5–52.2 months). This may be because most patients in both Medicare and the VHA were receiving ADT alone or with NSAA in the current study. If emerging disparities in TI in mCSPC are not addressed aggressively, selective increased use of TI in White patients, including treatment combinations, may further increase disparities in outcomes.

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations common in retrospective data analyses. First, this study only included patients who received systemic mCSPC treatment; there may be selection bias and findings may not be representative of all patients. Second, given the recent introduction of NHT, TI for mCSPC was low in 2018–2019 in both Medicare and the VHA. Thus, the impact of TI on OS suggested by multiple clinical trials has ostensibly not had a chance to manifest itself, nor is it possible to causally associate the impact of TI, or the lack thereof, with OS outcomes in mCSPC. Third, the Medicare and VHA data used in this study did not include information on some key prognostic factors, rendering it difficult to account for disease risk and volume. Additionally, while we were able to adjust for certain socioeconomic factors, other variables shown to be important to PC survival, such as marital status [62], were not available. Finally, we acknowledge that eligibility criteria for Medicaid differ by state and may have changed over time. Nonetheless, within a given state, those who are Medicaid-enrolled defines a group of patients at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. Further studies using more granular socioeconomic measures as well as social determinants of health are needed to understand which aspects of Medicaid eligibility are driving the associations seen.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that TI in mCSPC is slowly increasing, but remains low overall, despite unanimous guideline recommendations and evidence of OS improvement. TI is consistently lower in Black vs White patients in both Medicare and the VHA. Race was associated with OS in Medicare but not in the VHA. Importantly, our study shows that Medicare patients who were Medicaid-enrolled received less TI and had worse OS in mCSPC. This suggests that poverty, in addition to race, is associated with quality of care and outcomes. It is concerning that treatment disparities and potentially worse survival outcomes are emerging in mCSPC when life-prolonging treatments are available and established as the standard of care. There is an important role for guideline committees and healthcare practitioners, as well as population-based decision-makers such as those overseeing treatment pathways and algorithms, in ensuring that TI is provided, as appropriate, to patients with mCSPC, regardless of economic status or race.

Data availability

As the data supporting the findings of this study were used under license for the current study, restrictions apply to the authors’ ability to make data publicly available. The data are available from the Research Data Assistance Center and the Veterans Health Administration.

References

Sweeney CJ, Chen Y-H, Carducci M, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–46.

Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:352–60.

Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:686–700.

James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:338–51.

Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Azad A, et al. ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2974–86.

Armstrong AJ, Azad AA, Iguchi T, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, Holzbeierlein J, et al. Improved Survival With Enzalutamide in Patients With Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1616–22.

Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, Chung BH, Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, et al. Apalutamide for Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13–24.

Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, Chung BH, Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, et al. Apalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: Final survival analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase III TITAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2294–303.

Smith MR, Hussain M, Saad F, Fizazi K, Sternberg CN, Crawford ED, et al. Darolutamide and survival in metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1132–42.

Virgo KS, Rumble RB, Talcott J. Initial Management of Noncastrate Advanced, Recurrent, or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3652–6.

Lowrance WT, Breau RH, Chou R, Chapin BF, Crispino T, Dreicer R, et al. Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline PART I. J Urol. 2021;205:14–21.

Lowrance W, Dreicer R, Jarrard DF, Scarpato KR, Kim SK, Kirkby E, et al. Updates to Advanced Prostate Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline (2023). J Urol. 2023;209:1082–90.

Mottet N, Cornford P, van den Berg RCN, Briers E, Eberli D, De Meerleer G, et al. EAU - EANM - ESTRO - ESUR - ISUP - SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. 2023. https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG-Guidelines-on-Prostate-Cancer-2023_2023-03-27-131655_pdvy.pdf.

Tagawa ST, Sandin R, Sah J, Mu Q, Freedland SJ. 679P Treatment patterns of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC): A real-world evidence study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S541–2.

Freedland SJ, Sandin R, Sah J, Emir B, Mu Q, Ratiu A, et al. Treatment patterns and survival in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer in the US Veterans Health Administration. Cancer Med. 2021;10:8570–80.

Ryan CJ, Ke X, Lafeuille M-H, Romdhani H, Kinkead F, Lefebvre P, et al. Management of Patients with Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer in the Real-World Setting in the United States. J Urol. 2021;206:1420–9.

Swami U, Sinnott JA, Haaland B, Sayegh N, McFarland TR, Tripathi N, et al. Treatment pattern and outcomes with systemic therapy in men with metastatic prostate cancer in the real-world patients in the United States. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:4951.

Wallis CJD, Malone S, Cagiannos I, Morgan SC, Hamilton RJ, Basappa NS, et al. Real-world use of androgen-deprivation therapy: Intensification among older canadian men with de novo metastatic prostate cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5:pkab082.

Swami U, Hong A, El-Chaar NN, Nimke D, Ramaswamy K, Bell EJ, et al. Real-world first-line (1L) treatment patterns in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) in a U.S. health insurance database. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):5072.

George DJ, Agarwal N, Rider JR, Li B, Shirali R, Sandin R, et al. Real-world treatment patterns among patients diagnosed with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) in community oncology settings. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):5074.

Yip S, Niazi T, Hotte SJ, Lavallee L, Finelli A, Kapoor A, et al. Evolving real-world patterns of practice in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC): The genitourinary research consortium (GURC) national multicenter cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6_suppl):86.

Freedland SJ, Klaassen ZWA, Agarwal N, Sandin R, Leith A, Ribbands A, et al. Reasons for oncologist and urologist treatment choice in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC): A physician survey linked to patient chart reviews in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16_suppl):5065.

Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Ziehr DR, Hyatt AS, Sammon JD, Schmid M, et al. Trends in disparate treatment of African American men with localized prostate cancer across National Comprehensive Cancer Network risk groups. Urology. 2014;84:386–92.

Moses KA, Orom H, Brasel A, Gaddy J, Underwood W 3rd. Racial/ethnic differences in the relative risk of receipt of specific treatment among men with prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:415.e7–12

Gerhard RS, Patil D, Liu Y, Ogan K, Alemozaffar M, Jani AB, et al. Treatment of men with high-risk prostate cancer based on race, insurance coverage, and access to advanced technology. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:250–6.

Khan S, Hicks V, Rancilio D, Langston M, Richardson K, Drake BF. Predictors of Follow-Up Visits Post Radical Prostatectomy. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12:760–5.

Beebe-Dimmer JL, Ruterbusch JJ, Cooney KA, Bolton A, Schwartz K, Schwartz AG, et al. Racial differences in patterns of treatment among men diagnosed with de novo advanced prostate cancer: A SEER-Medicare investigation. Cancer Med. 2019;8:3325–35.

Caram MEV, Burns J, Kumbier K, Sparks JB, Tsao PA, Chapman CH, et al. Factors influencing treatment of veterans with advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. 2021;127:2311–8.

Mouzannar A, Atluri VS, Mason M, Prakash NS, Kwon D, Nahar B, et al. PD34-03 Racial disparity in the utilization of new therapies for advanced prostate cancer. J Urol. 2021;206(3_suppl):e583.

Rude T, Walter D, Ciprut S, Kelly MD, Wang C, Fagerlin A, et al. Interaction between race and prostate cancer treatment benefit in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2021;127:3985–90.

Kelly SP, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF, Andreotti G, Younes N, Cleary SD, et al. Trends in the Incidence of Fatal Prostate Cancer in the United States by Race. Eur Urol. 2017;71:195–201.

Tsodikov A, Gulati R, de Carvalho TM, Heijnsdijk EAM, Hunter-Merrill RA, Mariotto AB, et al. Is prostate cancer different in black men? Answers from 3 natural history models. Cancer. 2017;123:2312–9.

Weiner AB, Matulewicz RS, Tosoian JJ, Feinglass JM, Schaeffer EM. The effect of socioeconomic status, race, and insurance type on newly diagnosed metastatic prostate cancer in the United States (2004-2013). Urol Oncol. 2018;36:91.e91–6.

DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:211–33.

Würnschimmel C, Wenzel M, Collà Ruvolo C, Nocera L, Tian Z, Saad F, et al. Life expectancy in metastatic prostate cancer patients according to racial/ethnic groups. Int J Urol. 2021;28:862–9.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33.

Yamoah K, Lee KM, Awasthi S, Alba PR, Perez C, Anglin-Foote TR, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Prostate Cancer Outcomes in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2144027.

Elliott B, Zackery DL, Eaton VA, Jones RT, Abebe F, Ragin CC, et al. Ethnic differences in TGFβ-signaling pathway may contribute to prostate cancer health disparity. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39:546–55.

Zhang W, Dong Y, Sartor O, Flemington EK, Zhang K. SEER and Gene Expression Data Analysis Deciphers Racial Disparity Patterns in Prostate Cancer Mortality and the Public Health Implication. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6820.

Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, Soni PD, Jackson WC, Cooperberg MR, et al. Association of black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:975–83.

Krimphove MJ, Cole AP, Fletcher SA, Harmouch SS, Berg S, Lipsitz SR, et al. Evaluation of the contribution of demographics, access to health care, treatment, and tumor characteristics to racial differences in survival of advanced prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019;22:125–36.

Stern N, Ly TL, Welk B, Chin J, Ballucci D, Haan M, et al. Association of Race and Ethnicity With Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality in Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2136364.

Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, Vitzthum LK, Deka R, Sarkar RR, et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic white men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126:1683–90.

Balakrishnan AS, Palmer NR, Fergus KB, Gaither TW, Baradaran N, Ndoye M, et al. Minority Recruitment Trends in Phase III Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials (2003 to 2014): Progress and Critical Areas for Improvement. J Urol. 2019;201:259–67.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. About VHA. 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9.

Austin PC. Propensity-score matching in the cardiovascular surgery literature from 2004 to 2006: a systematic review and suggestions for improvement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1128–35.

Austin PC. A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003. Stat Med. 2008;27:2037–49.

Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, et al. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–98.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Other Non-Disabled Adults, 2011-2023. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-other-non-disabled-adults/.

Lowder D, Rizwan K, McColl C, Paparella A, Ittmann M, Mitsiades N, et al. Racial disparities in prostate cancer: A complex interplay between socioeconomic inequities and genomics. Cancer Lett. 2022;531:71–82.

Halabi S, Dutta S, Tangen CM, Rosenthal M, Petrylak DP, Thompson IM Jr, et al. Overall survival of black and white men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:403–10.

Sartor O, Armstrong AJ, Ahaghotu C, McLeod DG, Cooperberg MR, Penson DF, et al. Survival of African-American and Caucasian men after sipuleucel-T immunotherapy: outcomes from the PROCEED registry. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23:517–26.

Zhao H, Howard LE, De Hoedt A, Terris MK, Amling CL, Kane CJ, et al. Racial discrepancies in overall survival among men treated with 223radium. J Urol. 2020;203:331–7.

Cole AP, Herzog P, Iyer HS, Marchese M, Mahal BA, Lipsitz SR, et al. Racial differences in the treatment and outcomes for prostate cancer in Massachusetts. Cancer. 2021;127:2714–23.

George DJ, Ramaswamy K, Huang A, Russell D, Mardekian J, Schultz NM, et al. Survival by race in men with chemotherapy-naive enzalutamide- or abiraterone-treated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25:524–30.

Marar M, Long Q, Mamtani R, Narayan V, Vapiwala N, Parikh RB. Outcomes Among African American and Non-Hispanic White Men With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer With First-Line Abiraterone. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2142093.

Bernard B, Muralidhar V, Chen Y-H, Sridhar SS, Mitchell EP, Pettaway CA, et al. Impact of ethnicity on the outcome of men with metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:1536–44.

Freeman MM, Jaeger E, Zhu J, Phone A, Nussenzveig R, Caputo S, et al. Multi-institutional evaluation of the clinical outcomes and genomic correlates of African Americans with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(6_suppl):17.

Smith KER, Brown JT, Wan L, Liu Y, Russler G, Yantorni L, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Racial Disparities in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer in the Era of Novel Treatment Options. Oncologist. 2021;26:956–64.

Knipper S, Preisser F, Mazzone E, Mistretta FA, Palumbo C, Tian Z, et al. Contemporary analysis of the effect of marital status on survival of prostate cancer patients across all stages: A population-based study. Urol Oncol. 2019;37:702–10.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank everyone involved in this study. Medical writing support was provided by Kirstie Anderson and Matthieu Larochelle, and editorial support was provided by Rosie Henderson of Onyx (a division of Prime, London, UK) and funded by the sponsors, and by Flora Chik of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that provided paid consulting services to the sponsors.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) and Astellas Pharma Inc. (Northbrook, IL, USA), the co-developers of enzalutamide. The sponsors were involved in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data provided in the manuscript. However, ultimate responsibility for opinions, conclusions, and data interpretation lies with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: All authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: HY, WG, WS, YL. Obtained funding: KR, DR, BE, AH, RS. Administrative, technical, or material support: KR, DR, BE, YL, AH, RS. Supervision: KR, RS, WG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

DJG reports other from American Association for Cancer Research; grants and personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc.; personal fees from AstraZeneca; personal fees from Axess Oncology; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Bayer H/C Pharmaceuticals; grants and personal fees from BMS; grants from Calithera; grants from Capio Biosciences; grants from EMD Serono; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Exelixis Inc; personal fees from Flatiron; grants and personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals; personal fees from Merck, Sharp & Dohme; personal fees from Michael J Hennessey Assoc; personal fees from Millennium Medical Publishing; personal fees from Myovant Sciences Inc.; personal fees from NCI Genitourinary; grants and personal fees from Novartis; personal fees from Physician Education Resource; personal fees from Propella Therapeutics; grants and personal fees from Pfizer Inc.; personal fees from RevHealth; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Sanofi; personal fees from Seattle Genetics; personal fees from UroGPO; personal fees and non-financial support from UroToday; personal fees from WebMD; personal fees from Xcures. NA reports no personal conflicts of interest since April 15, 2021; lifetime conflicts of interest include consultancy to Astellas Pharma Inc., Astra Zeneca, Aveo, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calithera, Clovis, Eisai, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Foundation Medicine, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, MEI Pharma, Nektar, Novartis, Pfizer Inc., Pharmacyclics, and Seattle Genetics; research funding to institution from Arnivas, Astellas Pharma Inc., Astra Zeneca, Bavarian Nordic, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calithera, Celldex, Clovis, Crispr, Eisai, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Genentech, Gilead, Glaxo Smith Kline, Immunomedics, Janssen, Lava, Medivation, Merck, Nektar, Neoleukin, New Link Genetics, Novartis, Oric, Pfizer Inc., Prometheus, Rexahn, Roche, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Takeda, and Tracon. KR, DR, and RS own stocks or stock options and are employees of Pfizer Inc., a study sponsor. ZK reports serving on advisory boards for Bayer, Astellas Pharma Inc., Myovant, and Pfizer; consulting to Sesen Bio; and serving on a speakers’ bureau for Lantheus. RLB reports no disclosures. BE is an employee of Pfizer Inc., a study sponsor. HY, WS, and WG are employees of Analysis Group, which was a paid consultant to the sponsors in connection with the development of this manuscript. YL is co-owner of BRAVO4HEALTH LLC. AH is an employee of Pfizer Inc., a study sponsor; was an employee of Astellas Pharma Inc., a study sponsor, at the time of the study; and owns stock in Veru, Revance, and Insmed. SJF reports consulting to Pfizer Inc., Astellas Pharma Inc., Janssen, Dendreon, Sanofi, Myovant, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis, and Bayer. No other disclosures were reported.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the New England Independent Review Board and conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

George, D.J., Agarwal, N., Ramaswamy, K. et al. Emerging racial disparities among Medicare beneficiaries and Veterans with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-024-00815-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-024-00815-1