Abstract

The aim of this multicenter retrospective study is to characterize the histopathologic features of initial/early biopsies of proliferative leukoplakia (PL; also known as proliferative verrucous leukoplakia), and to analyze the correlation between histopathologic features and malignant transformation (MT). Patients with a clinical diagnosis of PL who have at least one biopsy and one follow-up visit were included in this study. Initial/early biopsy specimens were reviewed. The biopsies were evaluated for the presence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCCa), oral epithelial dysplasia (OED), and atypical verrucous hyperplasia (AVH). Cases that lacked unequivocal features of dysplasia were termed “hyperkeratosis/parakeratosis not reactive (HkNR)”. Pearson chi-square test and Wilcoxon test were used for statistical analysis. There were 86 early/initial biopsies from 59 patients; 74.6% were females. Most of the cases had a smooth/homogenous (34.8%) or fissured appearance (32.6%), and only 13.0% had a verrucous appearance. The most common biopsy site was the gingiva/alveolar mucosa (40.8%) and buccal mucosa (25.0%). The most common histologic diagnosis was OED (53.5%) followed by HkNR (31.4%). Of note, two-thirds of HkNR cases showed only hyperkeratosis and epithelial atrophy. A lymphocytic band was seen in 34.8% of OED cases and 29.6% of HkNR cases, mostly associated with epithelial atrophy. Twenty-eight patients (47.5%) developed carcinoma and 28.9% of early/initial biopsy sites underwent MT. The mortality rate was 11.9%. Our findings show that one-third of cases of PL do not show OED with most exhibiting hyperkeratosis and epithelial atrophy, but MT nevertheless occurred at such sites in 3.7% of cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia is a term originally introduced by Hansen et al.1 and currently defined by the World Health Organization as “a distinct and aggressive form of oral potentially malignant disorder; it is multifocal, has a progressive course, and is associated with high recurrence and malignant transformation rates”2. However, many lesions are not verrucous but rather homogenous or even have an erythematous component, and as such the term proliferative leukoplakia (PL) will be used here for accuracy3. PL is more common among non-smoker females in the 6th decade of life and the most frequently affected sites are the gingiva (57–78%), buccal mucosa (56–72%), and tongue (35–60%)3,4,5,6,7.

The prevalence of oral epithelial dysplasia (OED) and carcinoma in biopsies of PL varies from 23 to 97%1,3,7,8,9,10,11,12. Silverman and Gorsky8 reported that 52% of initial PL biopsies and 20% of last biopsies did not show OED or carcinoma, suggesting that the discrepancy in the percentage of OED/SCCa can be explained by the stage at which the PL lesions were biopsied. Only a minority of studies described the early biopsies of PL cases3,7,8,12.

The aim of this retrospective study is to analyze the histopathologic features of first or early biopsies of patients with PL, to describe histopathologic features of biopsies that do not show OED, and to analyze the correlation between histopathologic features and malignant transformation (MT).

Materials and methods

Three centers participated in this study, namely the Division of Oral Medicine and Dentistry at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), the Department of Stomatology at AC Camargo Cancer Center, and the Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, Radiology and Medicine at New York University College of Dentistry (NYU), and their medical records were searched from August 1996 to October 2016. Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

1.

A clinical diagnosis of PL (including verrucous, homogenous, and erythroleukoplakia subtypes) according to previously published criteria3.

-

2.

At least one biopsy.

-

3.

At least one follow-up visit.

Patients’ demographics and clinical histories (age, sex, smoking status, personal history of cancer or immunologic disease, and family history of cancer) were obtained from medical records. Initial and early biopsy specimens that were performed at each institution were retrieved and reviewed by an oral and maxillofacial pathologist (SW). An initial biopsy represented the patient’s first biopsy, whereas an early biopsy was defined as the first biopsy performed at one of the three institutions but where the patient had had a previous biopsy performed at a different institution usually many years prior and as such, could not be located for review.

The biopsies were evaluated for the presence of OED, carcinoma in situ, atypical verrucous hyperplasia (AVH)13, and squamous cell carcinoma (SCCa). The word “atypical” was added to verrucous hyperplasia so that clinicians understand these are not just a benign epithelial hyperplasia with a verrucous surface but is dysplastic. Lesions that showed bulky epithelial proliferation in an endophytic pattern, three to four times the normal thickness of epithelium for that site, with broad pushing borders, lacking conventional single cell and small or large island invasion were termed “atypical bulky endophytic squamous proliferation (ABESP)”. These are similar to the lesions categorized as “bulky hyperkeratotic epithelial proliferation, not reactive” as well as lesions classified as “suspicious for squamous cell carcinoma”14,15. These have been referred to also as “bluntly invasive squamous cell carcinoma”16. Cases that showed hyper(ortho)keratosis (Hk) and/or parakeratosis (Pk) and lacked unequivocal features of epithelial dysplasia or had mild atypia were reported as “Hk not reactive (HkNR)”15,17,18. These were comparable to the category of “corrugated ortho(para) hyperkeratotic lesion, not reactive” as described by Thompson et al.15.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee (2017P000100), the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (i18-01237), and A.C. Camargo Ethics committee (1908/14).

Statistical analysis

Follow-up periods were calculated from the initial visit to the most recent visit, censored in July 2020. MT was recorded when a patient developed SCCa including ABESP and verrucous carcinoma. Pearson chi-square test was used to assess the correlation between various variables and MT, as well as difference in histopathologic features between AVH, OED, and HkNR. Wilcoxon test was used to assess if there was a significant difference in follow-up periods between patients who underwent MT and those who did not undergo MT. Alpha was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 15 software (SAS Institute Inc.) and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 8 software (La Jolla California USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and clinical features

A total of 86 biopsies from 59 patients were included in this study with 17 patients having two or more biopsies (initial/early). Forty-three patients (70 biopsies) were from BWH, 10 from ACC, and 6 from NYU. Fifty-one biopsies from 43 patients represented the patients’ first or initial biopsies and 35 biopsies from 16 patients represented early biopsies. Twenty-nine cases had been previously published by Villa et al.3 in 2018.

Patients’ demographics and clinical features are shown in Table 1. There were 44 females (74.6%) and 15 males (25.4%), with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1. The median age was 65 years (mean 62.7 years); 84.8% of patients were 50 years or older.

More than half of the patients were never smokers (n = 33/57; 57.9%) and only 1 patient was a current smoker. A personal history of non-oral and non-skin cancer was present in 28.6% (n = 14/49) and four patients had chronic graft-versus-host disease. A family history of cancer was present in 86.8% (n = 33/38) of patients and one patient had dyskeratosis congenita.

The majority of the cases had smooth/homogenous (34.8%) and fissured leukoplakia (32.6%), with less than one-third having a verrucous appearance (13.0%, Fig. 1). The most common sites for initial/early biopsies were the gingiva/alveolar mucosa (40.8%) followed by the tongue (31.6%), buccal mucosa (25.0%), floor of mouth (1.3%), and hard palatal mucosa (1.3%). Ten biopsies did not have a specific site.

Histopathologic diagnosis

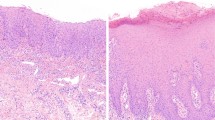

The histologic diagnoses are presented in Table 2 and the histologic diagnoses for each site are presented in Fig. 2. The most common histologic diagnosis was OED (53.5%), followed by HkNR (31.4%); AVH which is a form of dysplasia by architecture constituted another 3.5% of cases (Fig. 3). There were ten cases of SCCa, including four ABESPs that likely represent a form of invasive carcinoma that has been referred to as barnaculate carcinoma15 (Fig. 4) and the gingiva/alveolar mucosa was the single site with the highest involvement by SCCa.

A Verrucous leukoplakia of buccal mucosa, vestibule, and buccal gingiva. B Low power view of the biopsy from A with a verrucopapillary surface and marked epithelial hyperplasia (original magnification ×20). C Cytologic features of dysplasia were not seen (original magnification ×200). D, E Multifocal verrucous leukoplakia of the buccal marginal gingivae. F Low power view of the biopsy from the gingiva showing marked corrugated hyperkeratosis and epithelial hyperplasia (original magnification ×20) and mild epithelial dysplasia (G original magnification ×200).

Table 3 describes the histopathologic features of AVH, OED, and HkNR cases. Of note, a corrugated surface was observed in less than one-third of OED and HkNR cases (26.1% and 29.6%, respectively). Importantly, approximately two-thirds of cases had epithelial atrophy (Fig. 5). In addition, the presence of inflammation was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in AVH and OED than HkNR.

A Leukoplakia on the tongue dorsum and B biopsy that showed demarcated hyperkeratosis with epithelial atrophy (i.e., loss of tongue papillae; original magnification ×100) with minimal cytologic atypia (C original magnification ×400). D Homogenous proliferative leukoplakia of the upper right palatal gingiva. E Biopsy from D showed hyperkeratosis with minimal cytologic atypia present (original magnification ×400). F The leukoplakia in D developed a SCCa in 6 months (arrow). G Fissured leukoplakia of the left buccal mucosa, vestibule and buccal gingiva. H Biopsy from G showed hyperkeratosis with marked epithelial atrophy (original magnification ×100). I High-power view of H with minimal cytologic atypia (original magnification ×400).

A lymphocytic band (LB) was noted in 16 and 8 cases associated with OED and HkNR, respectively (Fig. 6). Almost half of the cases with a LB occurred on the gingiva (47.6%) and were associated with epithelial atrophy (n = 13/24; 54.2%).

A–E Multifocal leukoplakia of the maxillary and mandibular buccal and lingual gingivae and right and left buccal mucosae. F Biopsy of the leukoplakia in E that showed hyperkeratosis with keratin thickness greater than half the thickness of atrophic epithelium and a lymphocytic band (original magnification ×100). G High power view showing lack of cytologic atypia (original magnification ×400). H–I Moderate epithelial dysplasia of the ventral tongue with a lymphocytic band (original magnification ×100–200).

Of the 17 patients who had more than one biopsy, 82.4% (14/17) showed OED or carcinoma in at least one of those biopsies, while of the 42 patients who had a single biopsy, 73.8% (31/42) showed OED or carcinoma (p > 0.05).

Follow-up and malignant transformation

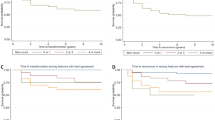

The median follow-up period was 53 months (range: 4-256). Twenty-eight patients (47.5%) developed 54 SCCas (including 3 verrucous carcinomas); 13 of 28 patients (46.4%) had >1 carcinoma and 6 patients had ≥3 carcinomas (Table 4). Twenty-two of 76 (28.9%) initial/early biopsy sites showed site-specific MT and the initial diagnosis of these cases was OED in 10 cases, SCCa in 10 cases, AVH in 1 case, and HkNR in 1 case. Of note, 22.2% (6/27) cases of HkNR showed OED on subsequent biopsies over a median of 19.5 months (range 2–41 months). The median follow-up period for patients who experienced MT was 56 (range 9–256) months compared to 35 months (range 4–173; p < 0.05) for those who did not undergo MT. The MT rates of patients with proliferative erythroleukoplakia, verrucous leukoplakia, smooth/homogenous leukoplakia, and fissured leukoplakia are 66.7%, 50.0%, 31.3%, and 26.7%, respectively (p > 0.05). Patients with contiguous and non-contiguous leukoplakias had similar MT rates (36.4% and 50.0%, respectively).

Mortality

Seven (11.9%) patients died, 6 from disease or effects of therapy, and one of unknown cause. Five patients had more than one SCCa (Table 4). There were 14 initial/early biopsies, and the most common initial diagnosis was OED (64.3%) followed by HkNR (28.6%). Seventy-one percent of patients with HkNR survived while 51.7% and 85.7% of patients with OED and SCCa survived, respectively (p > 0.05; Fig. 7).

Discussion

PL is a form of leukoplakia with high recurrence and MT rates. Patients affected by PL are usually female non-smokers in their 7th decade4,5. We report a female-to-male ratio of 3:1, similar to the pooled ratio by a recent systematic review of 2.5:15. Only one patient (1.8%) in our series was a current smoker, and the rest were non-smokers (40.4% former smokers and 57.9% never smokers) and this is in keeping with other studies5,12,19. A personal history of non-oral, non-skin cancer, mostly epithelial malignancies was noted in 28.6% of patients. Patients with hematologic malignancies and chronic graft-versus-host disease who developed PL have been reported in a previous study20. The most common locations involved by PL in this study as with most other studies, are the gingiva/alveolar mucosa, tongue, and buccal mucosa3,4,5,6,7,19.

The clinical diagnostic criteria for PL have evolved through the years. In 2010, Cerero-Lapiedra et al. proposed a new diagnostic system for PL that takes into account lesions multifocality, surface architecture, size, and recurrence21. Although verrucous architecture is considered a major criterion, only 28% have been reported to have a verrucous surface clinically3, and in this series, only 13.0% had a verrucous appearance clinically. It is likely that some cases of fissured leukoplakia are diagnosed as verrucous leukoplakia because they are not smooth clinically, and because the histopathology of fissured lesions appear undulated or corrugated it may be signed out as verrucous in the pathology report. The word “verrucous” has created confusion in the past, as some pathologists refrain from suggesting a diagnosis of proliferative “verrucous” leukoplakia when verrucous architecture is not present and the term PL better reflects the clinical appearance of the lesion as well as the histopathology, since 70% of cases in this series did not have a corrugated/verrucous surface histopathologically. Simplified diagnostic criteria were proposed by Villa et al.3, which focus on multifocality, size including contiguity with adjacent sites, and clinical progression. Both systems emphasize that PL is a clinicopathologic entity.

Earlier and recent reports have shown that the pathologic diagnosis of PL can vary from HkNR to overt OED or carcinoma1,3,7,15,22. In general, the percentage of OED and carcinoma in PL biopsies has been reported to be 25% to 97%1,3,7,8,9,10,11,12. Four studies reported on initial/early biopsies and noted OED and carcinoma in 23–48% of cases3,7,8,12, while this figure ranged between 60 and 97% in other studies1,9,10,11. Our study showed OED in 53.5% of cases.

The non-OED and carcinoma cases constituted the rest of the cases and these were diagnosed as “clinical leukoplakia (Hansen grade 2)”1, “simple HK with little or no dysplasia”7, “hyperkeratosis without dysplasia”3, “hyperkeratosis/hyperplasia”8, “hyperkeratosis, no dysplasia”9, “PVL with atypia and atrophy”10, and “hyperkeratosis and acanthosis”11. These diagnostic terms could just as well represent chronic frictional keratoses including benign alveolar ridge keratoses and that is why the diagnostic term HkNR or “corrugated ortho (para)keratotic lesion, not reactive” is favored to indicate these are not reactive lesions. This has been proposed by Thompson et al.15 and others for uniform reporting of these entities14,17,18. In this series of 86 initial/early biopsies from 3 centers, 31.4% showed hyperkeratosis and/or parakeratosis with epithelial atrophy or acanthosis, but without overt evidence of OED. Hyperkeratosis with epithelial atrophy was also noted by Thompson et al.15 and the two together is an important feature seen in the biopsies of patients with PL. A putative model for evolution of PL to carcinoma is presented in Fig. 8.

Leukoplakia affecting the oral mucosa may present histologically as atypical verrucous hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, not reactive with epithelial atrophy or acanthosis, oral epithelial dysplasia, or carcinoma. Hyperkeratosis, not reactive has the potential to progress into atypical verrucous hyperplasia or oral epithelial dysplasia, which in turn may undergo malignant transformation into verrucous carcinoma, atypical bulky endophytic epithelial proliferation, or conventional squamous cell carcinoma.

ABESP is a controversial concept. This is a bulky squamous proliferation, three to four times the thickness of the epithelium for the site, that is endophytic and/or exophytic in its growth pattern similar to that of verrucous carcinoma, exhibits cytologic atypia to varying degrees but without single cell or small island infiltration of the stroma (Fig. 4). These are not benign reactive epithelial hyperplasias such as are seen in reaction to friction or trauma and are a common feature in PL as noted by Thompson et al.15 and in solitary lesions noted by Wang et al.16. Because its pattern of invasion is blunt and broad similar to verrucous carcinoma, it is unlikely to metastasize. More research will be needed to further characterize this lesion.

A LB was noted in 24 biopsies (n = 24/76; 31.6%), mostly from the gingiva/alveolar mucosa. In a series of 168 localized leukoplakia, Woo et al.23 reported that a LB with epithelial atrophy was seen in 7.2% (7/96) of the non-dysplastic non-reactive cases (formerly known as keratosis of unknown significance [KUS]). More recently, Alabdulaaly et al.17 noted a LB in 23.5% of presumptive PL cases. In this study, eight HkNR (n = 8/27, 29.6%) cases had a LB, six of which were associated with epithelial atrophy. Furthermore, the presence of inflammation was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in OED and AVH compared to HkNR and both had higher MT than HkNR cases. A recent study on 20 cases of PL reported lichenoid features in 40% of cases7. The presence of a LB, which occasionally is often reported as “lichenoid mucositis”, may have led to some cases of PL being diagnosed as lichen planus12,13. Additionally, a LB is seen not infrequently in SCCas, verrucous carcinoma (70%), AVH (33%), and OED (29%)24,25.

We believe that the presence of LB in the setting of localized and PL reflects a lymphocytic response to the neo-antigens within these lesions This lymphocytic T-cell response has been shown to be an independent and favorable prognostic indicator in oral SCCa26,27. Checkpoint inhibitors, which promote this response, are currently employed for the treatment of various cancers, including head and neck SCCa28,29. Furthermore, the presence of a LB is seen in increasing frequency from HkNR at 29.6% to OED at 34.8% which suggests that lesions exhibiting HkNR may represent the breakthrough phase on the path to carcinogenesis resulting in their recognition by T-cells30.

Biopsies that show hyperkeratosis without OED have been reported to undergo MT, both in PL and localized leukoplakias in 3-15% of cases3,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. One patient with HkNR in this series underwent MT after 14 months and his subsequent course was complicated by cancer at other oral sites and multiple recurrences, ultimately with extension of a palatal SCCa to the skull base leading to the patient’s demise. Goodson et al.38 analyzed 58 SCCa that developed from precursor lesions. One-third of these showed Hk and lichenoid inflammation38. Chaturvedi et al. reported MT in 9% of cases of HkNR in the setting of localized leukoplakia36. Holmstrup et al.31 reported a similar MT rate (11%) in biopsies with mild dysplasia and those without dysplasia, both higher than moderate and severe dysplasia31. A recent review reported a MT rate of 4.9% in leukoplakias that exhibit hyperkeratosis without OED (HkNR)39, similar to the MT rate of mild dysplasia at 3.9–5.7%2,40,41 suggesting that HkNR should be considered a mild OED.

The overall MT rate of PL ranges from 44% to 100% over an average follow-up period of 44.8–91.8 months3,5,7,42,43, and increased MT rate has been shown to be proportional to the length of the follow-up period; patients who did not undergo MT had shorter follow-up periods3,7,44. Approximately half of the patients in our series underwent MT over a median follow-up period of 53 months, which is similar to what was reported by a recent meta-analysis (43.9%)43. Patients who developed malignancy had a longer follow-up period than those who did not (median of 56 and 35 months respectively, p < 0.05). Interestingly, while the overall MT rate by patients was 47.5%, the site-specific MT rate was 28.9%, implying that patients developed malignancy in locations other than the sites biopsied at their initial presentation. This is possible because biopsies were obtained from sites that looked worrisome clinically yet progressed at a slower rate than sites that looked clinically innocuous. Furthermore, second primary SCCa developed in 13 patients in this series, with six patients experiencing three or more SCCa, similar to cases reported by Bagan et al.45. In addition, the survival of patients diagnosed with HkNR at the initial/early biopsy was not significantly different from those diagnosed with OED and SCCa. Some possible explanations include the unpredictability of PL and/or that a diagnosis of “hyperkeratosis, no dysplasia” leads to complacency. On the other hand, patients with an initial diagnosis of SCCa had a higher survival rate than those diagnosed with OED and HkNR (p > 0.05), and this can be explained by the low number of SCCa cases which includes four ABESP in addition the short follow-up period of the SCCa group (123 months) compared to the OED (256 months) and HkNR (173 months) cases. What is important is that multiple biopsies from various sites coupled with close follow-up is needed for patients with PL. Even though there was no significant difference in the prevalence of OED and SCCa between patients who had a single biopsy vs. multiple biopsies, it is important that multiple biopsies be performed since pathology can vary greatly from site to site.

The biologic nature of these non-dysplastic keratoses remains to be elucidated. We previously showed that both non-dysplastic and dysplastic keratoses share the same structural variants in KMT2C, TP53, and TIAM1, with dysplastic cases having greater single nucleotide variants (SNV) than non-dysplastic cases. Interestingly, HkNR lesions of PL had higher SNVs than those of localized leukoplakia. 83 and 50% of dysplastic and non-dysplastic keratoses underwent MT37. Furthermore, DNA aneuploidy has been reported in PL cases that lack OED46,47. On the other hand, Farah and Fox48 suggested that keratoses with and without dysplasia represent two different entities with respect to their molecular signature. Differential gene expression analysis revealed two clusters of keratoses lacking OED with one cluster exhibiting a higher resemblance to OED than the other48.

One of the major drawbacks of this study is the short follow-up period. It has been reported that the MT rate of PL is time dependent. If the entire cohort had been followed for a longer period, the incidence of MT would likely be higher3. Another shortcoming is the small sample number, which decreases the power of the statistical analysis. However, this limitation cannot be overcome due to the rarity of PL. Finally, more research needs to be performed to elucidate the mutational landscape of lesions of HkNR and the lymphocytic response so that we can better understand their biology and perhaps be able to utilize targeted therapy in their management.

In conclusion, we characterized 86 initial/early PL biopsies from 59 patients, and these are the key features.

-

70% of initial/early biopsies did not exhibit a corrugated or verrucous architecture.

-

Approximately 1/3 of cases were HkNR and approximately half showed OED.

-

Epithelial atrophy was almost twice as common in HkNR (63.0%) than OED (34.8%)

-

A LB was present in 1/3 of cases of OED and HkNR.

-

MT occurred at a rate of 47.5%, with only 28.9% of initial/early biopsy sites undergoing site-specific MT.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Hansen, L. S., Olson, J. A. & Silverman, S. Jr. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. A long-term study of thirty patients. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 60, 285–298 (1985).

El-Naggar, A., Chan, J., Grandis, J., Takata, T. & Slootweg, P. World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors. 4th edn, (IARC: Lyon, 2017).

Villa, A. et al. Proliferative leukoplakia: proposed new clinical diagnostic criteria. Oral Dis. 24, 749–760 (2018).

Bagan, J. et al. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: high incidence of gingival squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 32, 379–382 (2003).

Pentenero, M., Meleti, M., Vescovi, P. & Gandolfo, S. Oral proliferative verrucous leucoplakia: are there particular features for such an ambiguous entity? A systematic review. Br. J. Dermatol. 170, 1039–1047 (2014).

Garcia-Chias, B., Casado-De La Cruz, L., Esparza-Gomez, G. C. & Cerero-Lapiedra, R. Diagnostic criteria in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: evaluation. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 19, e335–e339 (2014).

Upadhyaya, J. D., Fitzpatrick, S. G., Islam, M. N., Bhattacharyya, I. & Cohen, D. M. A retrospective 20-year analysis of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its progression to malignancy and association with high-risk human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 12, 500–510 (2018).

Silverman, S. & Gorsky, M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a follow-up study of 54 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 84, 154–157 (1997).

Bagan, J. V. et al. Lack of association between proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and human papillomavirus infection. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 65, 46–49 (2007).

Kresty, L. A. et al. Frequent alterations of p16INK4a and p14ARF in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 17, 3179–3187 (2008).

Gouvea, A. F., Vargas, P. A., Coletta, R. D., Jorge, J. & Lopes, M. A. Clinicopathological features and immunohistochemical expression of p53, Ki-67, Mcm-2 and Mcm-5 in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 39, 447–452 (2010).

McParland, H. & Warnakulasuriya, S. Lichenoid morphology could be an early feature of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 50, 229–235 (2021).

Muller, S. Oral epithelial dysplasia, atypical verrucous lesions and oral potentially malignant disorders: focus on histopathology. Oral. Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radio. 125, 591–602 (2018).

Woo, S. B. Oral epithelial dysplasia and premalignancy. Head Neck Pathol. 13, 423–439 (2019).

Thompson, L. D. R., et al. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: an expert consensus guideline for standardized assessment and reporting. Head Neck Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-020-01262-9 (2021).

Wang, D., Chen, T., Menon, R., Breitman, L. & Woo, S.-B. Clinical and histopathologic features of oral bluntly invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Abstract from USCAP 2020: Head Neck Pathol. (1308). Mod Pathol 33, 1237–1238 (2020).

Alabdulaaly, L., Almazyad, A. & Woo, S. B. Gingival leukoplakia: hyperkeratosis with epithelial atrophy is a frequent histopathologic finding. Head Neck Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01333-5 (2021).

Li, C. C., Almazrooa, S., Carvo, I., Salcines, A. & Woo, S. B. Architectural alterations in oral epithelial dysplasia are similar in unifocal and proliferative leukoplakia. Head Neck Pathol 15, 443–460 (2021).

Torrejon-Moya, A., Jane-Salas, E. & Lopez-Lopez, J. Clinical manifestations of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a systematic review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 49, 404–408 (2020).

Fantozzi, P. J., Villa, A., Antin, J. H. & Treister, N. Regression of oral proliferative leukoplakia following initiation of ibrutinib therapy in two allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 55, 1844–1846 (2020).

Cerero-Lapiedra, R., Balade-Martinez, D., Moreno-Lopez, L. A., Esparza-Gomez, G. & Bagan, J. V. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a proposal for diagnostic criteria. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.15.e839, e839-e845 (2010).

Batsakis, J., Suarez, P. & El-Naggar, A. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its related lesions. Oral Oncol. 35, 354–359 (1999).

Woo, S. B., Grammer, R. L. & Lerman, M. A. Keratosis of unknown significance and leukoplakia: a preliminary study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radio. 118, 713–724 (2014).

Fitzpatrick, S. G., Honda, K. S., Sattar, A. & Hirsch, S. A. Histologic lichenoid features in oral dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radio. 117, 511–520 (2014).

Davidova, L. A., Fitzpatrick, S. G., Bhattacharyya, I., Cohen, D. M. & Islam, M. N. Lichenoid characteristics in premalignant verrucous lesions and verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 13, 573–579 (2019).

Brandwein-Gensler, M. et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: histologic risk assessment, but not margin status, is strongly predictive of local disease-free and overall survival. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 29, 167–178 (2005).

Li, L. et al. Comprehensive immunogenomic landscape analysis of prognosis-related genes in head and neck cancer. Sci. Rep. 10, 6395 (2020).

Burtness, B. et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 394, 1915–1928 (2019).

FDA. FDA approves pembrolizumab for first-line treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-pembrolizumab-first-line-treatment-head-and-neck-squamous-cell-carcinoma (2019).

Vogelstein, B. & Kinzler, K. W. The path to cancer–three strikes and you’re out. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1895–1898 (2015).

Holmstrup, P., Vedtofte, P., Reibel, J. & Stoltze, K. Long-term treatment outcome of oral premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 42, 461–474 (2006).

Brouns, E. et al. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia in a well-defined cohort of 144 patients. Oral Dis. 20, e19–e24 (2014).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Malignant transformation in 5071 southern Taiwanese patients with potentially malignant oral mucosal disorders. BMC Oral Health 14, 99 (2014).

Mogedas-Vegara, A., Hueto-Madrid, J. A., Chimenos-Kustner, E. & Bescos-Atin, C. The treatment of oral leukoplakia with the CO2 laser: a retrospective study of 65 patients. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 43, 677–681 (2015).

Gandara-Vila, P. et al. Survival study of leukoplakia malignant transformation in a region of northern Spain. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 23, e413–e420 (2018).

Chaturvedi, A. K., et al. Oral leukoplakia and risk of progression to oral cancer: a population-based cohort study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djz238 (2019).

Villa, A. et al. Oral keratosis of unknown significance shares genomic overlap with oral dysplasia. Oral Dis. 25, 1707–1714 (2019).

Goodson, M. L., Sloan, P., Robinson, C. M., Cocks, K. & Thomson, P. J. Oral precursor lesions and malignant transformation—who, where, what, and when? Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 53, 831–835 (2015).

Stojanov, I. J. & Woo, S. B. Malignant transformation rate of non-reactive oral hyperkeratoses suggests an early dysplastic phenotype. Head Neck Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-021-01363-z (2021).

Wenig, B. M. Squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: dysplasia and select variants. Mod. Pathol. 30, S112–S118 (2017).

Sperandio, M. et al. Predictive value of dysplasia grading and DNA ploidy in malignant transformation of oral potentially malignant disorders. Cancer Prev. Res. 6, 822–831 (2013).

Morton, T., Cabay, R. & Epstein, J. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia and its progression to oral carcinoma: report of three cases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 36, 315–318 (2007).

Ramos-García, P., González-Moles, M., Mello, F. W., Bagan, J. V. & Warnakulasuriya, S. Malignant transformation of oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13831 (2021).

Bagan, J., Scully, C., Jimenez, Y. & Martorell, M. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a concise update. Oral Dis. 16, 328–332 (2010).

Bagan, J., Murillo-Cortes, J., Poveda-Roda, R., Leopoldo-Rodado, M. & Bagan, L. Second primary tumors in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia: a series of 33 cases. Clin. Oral Investig. 24, 1963–1969 (2020).

Klanrit, P. et al. DNA ploidy in proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Oral Oncol. 43, 310–316 (2007).

Gouvea, A. F. et al. High incidence of DNA ploidy abnormalities and increased Mcm2 expression may predict malignant change in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Histopathology 62, 551–562 (2013).

Farah, C. S. & Fox, S. A. Dysplastic oral leukoplakia is molecularly distinct from leukoplakia without dysplasia. Oral Dis. 25, 1715–1723 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.V. and S.W. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, and critically revised the manuscript. L.A., T.C., A.K, N.R., F.D.A.A., and A.G. collected the data. L.A. analyzed the data, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and drafted and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee (2017P000100), the New York University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (i18-01237), and A.C. Camargo Ethics committee (1908/14).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alabdulaaly, L., Villa, A., Chen, T. et al. Characterization of initial/early histologic features of proliferative leukoplakia and correlation with malignant transformation: a multicenter study. Mod Pathol 35, 1034–1044 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01021-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-022-01021-x