Abstract

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide imposed lockdown measures in early 2020, resulting in notable reductions in air pollutant emissions. The changes in air quality during the pandemic have been investigated in numerous studies via satellite observations. Nevertheless, no relevant research has been gathered using Chinese satellite instruments, because the poor spectral quality makes it extremely difficult to retrieve data from the spectra of the Environmental Trace Gases Monitoring Instrument (EMI), the first Chinese satellite-based ultraviolet–visible spectrometer monitoring air pollutants. However, through a series of remote sensing algorithm optimizations from spectral calibration to retrieval, we successfully retrieved global gaseous pollutants, such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and formaldehyde (HCHO), from EMI during the pandemic. The abrupt drop in NO2 successfully captured the time for each city when effective measures were implemented to prevent the spread of the pandemic, for example, in January 2020 in Chinese cities, February in Seoul, and March in Tokyo and various cities across Europe and America. Furthermore, significant decreases in HCHO in Wuhan, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Seoul indicated that the majority of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emissions were anthropogenic. Contrastingly, the lack of evident reduction in Beijing and New Delhi suggested dominant natural sources of VOCs. By comparing the relative variation of NO2 to gross domestic product (GDP), we found that the COVID-19 pandemic had more influence on the secondary industry in China, while on the primary and tertiary industries in Korea and the countries across Europe and America.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since early 2020, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), a severe infectious disease, began to spread worldwide. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide implemented special measures (lockdowns) to prevent crowd gathering, which have resulted in a global reduction in air pollutant emissions1,2. Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the variations in air quality owing to the pandemic. For instance, some studies have focused on the significant reduction in atmospheric nitrogen dioxide (NO2) from space-borne observations by high-resolution instruments, such as the Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) and Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI)3,4, based on in-situ monitoring5,6, and through atmospheric chemical transport modeling7,8. Satellite-based remote sensing has a distinctive advantage when compared to surface observations, especially in terms of spatial coverage and data consistency, which enable us to easily compare air quality discrepancies in different countries. For instance, Bauwens et al.3 and Sun et al.9 explored global changes in the levels of NO2 and formaldehyde (HCHO) through satellite observations.

The Environmental Trace Gases Monitoring Instrument (EMI) onboard the GaoFen-5 satellite is the first Chinese satellite-based ultraviolet–visible hyperspectral spectrometer (spectral resolution of <0.6 nm). Along with TROPOMI and OMI, it is also a space-borne high-resolution instrument for air pollutant observation. Because the original spectral quality of EMI is considerably inferior to that of TROPOMI, it has thus far not been used for air quality research during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, by conducting a series of optimizations from spectral calibration to inversion settings in our previous studies10,11, a comparable final inversion data quality with TROPOMI was achieved. In this study, we used the tropospheric vertical column densities (TVCDs) of multiple gaseous pollutants observed by EMI to investigate the variations, potentially caused by lockdown measures, in air pollutants such as NO2, sulfur dioxide (SO2), and HCHO across different countries and cities. In addition, the relationships between the pandemic, economy, and air quality are discussed.

Results

Retrieval of NO2, SO2, and HCHO from EMI

Launched in May 2018, EMI onboard the Gaofen-5 satellite is a push-broom spectrometer with ultraviolet and visible spectral bands from 240 to 710 nm and a nadir spatial resolution of 12 × 13 km2. The basic retrieval methods for EMI are similar to those for OMI and TROPOMI. The NO2 TVCDs are retrieved in three steps. First, the total NO2 slant column density (SCD) is retrieved using the differential optical absorption spectroscopy (DOAS) technique. As suggested by the QA4ECV NO2 project12, the absorption cross-section of ozone (O3), NO2, oxygen dimer (O4), water vapor, and liquid water, as well as ring effect, were considered. Subsequently, the tropospheric NO2 SCD is obtained after separating stratospheric NO2 through the STRatospheric Estimation Algorithm from Mainz13. Finally, air mass factors (AMFs) are used to convert tropospheric SCDs to tropospheric VCDs (TVCDs).

For HCHO retrieval, the first step is the retrieval of the differential slant column density (DSCD) by fitting radiances through the basic optical differential spectroscopy (BOAS) method. DSCD represents the difference between the true SCD value and SCD in the reference spectra (the daily earth radiance in the remote Pacific Ocean). Cross-sections of O3 at two temperatures, NO2, O4, and bromine monoxide (BrO) were considered in the retrieval of HCHO DSCDs14. Then, the DSCD is converted to SCD through reference sector correction, because earth radiance in the remote Pacific Ocean contains a small amount of HCHO absorption14,15,16. Similar to the conversion of NO2, the final step is the conversion of HCHO SCD to HCHO VCD using AMF. As HCHO is concentrated in the lower troposphere, the retrieved HCHO VCD is approximately equal to the HCHO TVCD. Further, because EMI shares the same overpass time as TROPOMI, in the AMF calculation for NO2 and HCHO retrieval, parameters including cloud information and surface albedo are from TROPOMI. Simulated profiles of NO2 and HCHO by the GEOS-Chem model are used as a priori profiles in the AMF calculation.

SO2 TVCDs are retrieved using the optimal estimation (OE) algorithm by minimizing the cost function. It simultaneously considers the difference between the simulated and measured reflectance and the difference between the retrieved and the a priori state vectors. The fitting is constrained by the measurement and a priori uncertainty covariance matrix. The vector linearized discrete ordinate radiative transfer model (VLIDORT) is then employed to simulate the radiance containing only Rayleigh scattering and O3 absorption. The Lambert-Beer Laws introduce other trace gases effects with the a priori profiles from the GEOS-Chem simulations. Cross-sections of O3 at four temperatures, BrO and HCHO were considered for SO2 retrieval17.

However, because of the poor original spectral quality of EMI (Fig. 1), the retrieval results are noisy and show unrealistic distributions without pre-calibrations (Fig. 2a–c). Therefore, we developed several new methods to improve the traditional retrieval.

-

(1)

The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the EMI instrumental spectral response functions (ISRFs) changes much more drastically than that of the TROPOMI ISRFs in spatial and temporal dimensions (Fig. 1), because the EMI instrument lacks preflight ISRFs and the instrument performance is degraded by the complex space environment. Simultaneously, the EMI wavelength shifts are much larger (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information). To address this problem, we performed on-orbit wavelength calibration to calculate daily ISRFs and wavelength shifts to diminish the fitting residuals.

-

(2)

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of EMI is very low, at only one-third of that of TROPOMI. Therefore, there was a need to minimize the interference of other trace gases in the retrieval fitting windows and reduce the fitting residual under such a low SNR of EMI. Here we set up an adaptive iterative retrieval algorithm that selects the retrieval setting best with minimum uncertainty among fitting results using different retrieval settings. The retrieval settings not only contain the fitting windows but also consider low-order polynomials and different trace gas parameters, etc. For instance, instead of directly using wavelength fitting ranges suggested in the retrievals from OMI and TROPOMI in previous studies, the wavelength fitting ranges were chosen by the adaptive iterative retrieval algorithm as 420–470 nm, 326.5–356 nm, and 310.5–320 nm for NO2, HCHO, and SO2 retrievals from EMI, respectively.

-

(3)

Owing to the insufficient mechanical structure of optical path switching, EMI only provides the solar spectrum once every 6 months. In addition, EMI provides abnormal irradiance measurements owing to a diffuser calibration issue. To obtain the requisite daily solar spectrum for the following retrieval algorithm, we used simulated irradiance instead of using measured irradiance. This eliminated the cross-track stripes in the retrieval and reduced the average fitting residuals.

Further, retrieval results were improved by obtaining algorithm updates (Fig. 2d–f). In particular, the spectra for SO2 retrieval contain more noise because the strongest SO2 absorption band (300–330 nm) is close to the edge of the measured spectra. Therefore, traditional retrieval settings greatly overestimate the SO2 TVCDs in China and India11. Improved SO2 data were obtained through the above three measures, as well as extra measurement error correction and pixel merging (Fig. 2e). The calibrated data from EMI were validated by surface observations in India and TROPOMI data retrieved using our improved algorithm11. The detailed retrieval algorithms for NO2, SO2, and HCHO from EMI are described in our previous studies10,11,18.

According to the uncertainty propagation, the systematic error of the NO2 TVCD is due to systematic uncertainty in SCD retrieval (<3%), AMF calculation (15–40%), and stratospheric separation (<10%). This caused a total systematic error of NO2 TVCDs of ~18% in the summer and 42% in the winter10,12. The systematic error of the HCHO VCD is due to systematic uncertainty in SCD retrieval (~17%), AMF calculation (15–51%), and reference sector correction (10–40%)14,19. Combined, these produce a total uncertainty of ~25% in clean regions and 67% in polluted regions. Uncertainty from the AMF calculation contributes the most to the systematic error of NO2 and HCHO TVCDs. The parameters used in the EMI AMF calculation are similar to the TROPOMI AMF calculation, and the systematic errors in these two retrievals are of the same order of magnitude. The SO2 concentration in the remote Pacific Ocean (10° S-10° N, 135°−90° W) is assumed to be zero. Therefore, the retrieved SO2 TVCD in the remote Pacific region is identified as the systematic error of SO2 TVCD retrieval, which is ~0.29 DU11.

Nevertheless, systematic retrieval errors will not affect the comparison of TVCDs in the years 2019 and 2020. However, the random error can be used to evaluate whether the satellite observation can capture the monthly variability of the pollutants20. The random retrieval error of air pollutants in the investigated city was calculated as \(\overline {{{{\mathrm{error}}}}} /\sqrt {n_{{{{\mathrm{pix}}}}}}\), where \(\overline {{{{\mathrm{error}}}}}\) is the average random retrieval error of all the satellite pixels over the city and npix is the number of pixels over the city20. Therefore, spatial sampling is the main factor influencing random error. The monthly TVCDs of NO2 and HCHO retrieved from EMI showed good consistency with those from the operational products of TROPOMI (Fig. 3), although the absolute values from the two instruments had some deviation and the random retrieval errors of HCHO from EMI were larger than those from TROPOMI. We did not compare the SO2 results from the two satellite instruments because of the systemic deviation of the operational SO2 products from TROPOMI21.

Correlation analysis of the monthly (a) NO2 TVCDs and b HCHO TVCDs from EMI and TROPOMI in the first quarter of 2019 and 2020 in Wuhan, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Seoul, Tokyo, Milan, Berlin, Paris, London, New York, New Delhi, and Rio de Janeiro. NO2 and HCHO TVCDs in a city were calculated as the average of TVCDs in satellite pixels within a radius of 50 km around the city center

Global air quality variations during COVID-19 pandemic from EMI observation

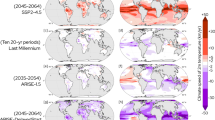

Nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO + NO2) are short-lived trace gas species produced by combustion emissions, such as coal combustion for power generation and industrial production, and from vehicle exhausts22,23. NO2 TVCD retrieved from satellite observations has been widely used to indicate anthropogenic emissions24,25. In March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic had spread all over the world, the global average NO2 TVCD from EMI observations was 1.3 × 1014 molecules cm−2 (20%) lower than that in March 2019. The reductions in NO2 TVCD were more evident in regions with high concentrations, such as eastern China, western Europe, and eastern North America (Fig. 4a). In most investigated cities, the monthly NO2 TVCDs showed good consistency with surface concentrations (Fig. S2). However, in Tokyo, Berlin, and Paris, the surface concentrations showed relatively narrower variations. Similar trends in the column and surface concentrations further confirmed the decrease in NOx emissions. In particular, when governments implemented active measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic, NO2 TVCD accordingly decreased abruptly4. Therefore, the changes in NO2 TVCD can reflect the response to the pandemic in different cities; this will be discussed in detail in the following section.

In addition to NO2, SO2 is also an important anthropogenic pollutant from power generation, oil refineries, smelters, and domestic heating26,27. In contrast to the significant reduction of NO2, SO2 TVCDs in March 2020 showed a slightly increasing global trend compared to that in March 2019 (Fig. 4b). With the application of desulfurization techniques, SO2 emissions have greatly decreased worldwide in recent years, and apart from in India, atmospheric SO2 worldwide dropped dramatically28,29. Obvious SO2 emission hotspots were only observable in India through satellite observation11. SO2 TVCDs from EMI in most of the other regions were noisy. Therefore, we specifically tracked the changes in SO2 in the Chhattisgarh-Odisha region in India, where various large coal-fired power plants are gathered and SO2 concentrations are among the highest in the world. When the pandemic struck India in March 2020, the observed SO2 TVCD was slightly higher than that in March 2019 (Fig. S3), and the random retrieval errors did not exceed the changes in the SO2 TVCDs. Furthermore, because the concentration of air pollutants can also be affected by meteorology, we adjusted the SO2 TVCDs in 2019 to those under the meteorological conditions of 2020 (deweathered SO2) according to GEOS-Chem modeling (seeing method). The results showed that the SO2 TVCD in March 2020 was much higher than the deweathered TVCD in March 2019, indicating that the power industry was unaffected by the pandemic until then. Other studies had similar findings. For instance, Zhang et al.30 found no obvious reductions in SO2 TVCDs in India during the first quarter of 2020 when compared to the first quarter of years 2015–2019. Instead, great reductions in SO2 levels were noted in April and May, likely due to the implementation of strict lockdown measures from late March. In addition, Shi et al.31 found no substantial change in SO2 in Chinese cities of Wuhan and Beijing during the lockdown period, further indicating that the main sources of SO2, such as residential heating and energy production, were not as easily affected by the pandemic as those of NO231.

HCHO in ambient air is formed by the atmospheric chemical reaction of non-methane hydrocarbons (NMHCs)32,33, as well as through direct emissions from anthropogenic activities and biomass burning34,35,36. HCHO TVCDs from satellite-based remote sensing has been widely used to trace VOC emissions37,38,39. The global average of HCHO TVCD in March 2020 was 1.5 × 1015 molecules cm−2 (21%) lower than that in March 2019. However, distinct variations were observed in the different regions (Fig. 4c). Similar variations in global NO2 and HCHO between March 2019 and March 2020 were also observed by TROPOMI (Fig. S4).

The change of NO2 from EMI observation indicates the lockdown measures in different cities

The monthly increase in infections of COVID-19 in China proliferated in January and reached a peak in February 2020 (Fig. S5). The COVID-19 pandemic first broke out in Wuhan, China, and the city has been under an emergent lockdown measure since January 23, 2020. Although the measure only covered nine days in January, the monthly NO2 TVCD in Wuhan from EMI observation, which was calculated as the average of TVCDs in all the satellite pixels within a radius of 50 km around the city center, decreased by 56% relative to that in January 2019 (Fig. 5a). Even after deducting the influence of meteorology, the NO2 TVCD in January 2020 decreased by 51%. In addition, the random retrieval errors were less than 1% of the monthly TVCDs, which were much lower than the change in NO2 TVCDs. Therefore, the sharp variation in NO2 TVCD in January 2020 can be attributed to a significant reduction in emissions. The annual one-week-long Chinese New Year (CNY) holiday occurred in January of 2020 but in February of 2019. Therefore, the decline in NO2 from January 2019 to January 2020 included the influence of the holiday effect. By directly comparing NO2 TVCDs during the CNY week in both years, we found a decrease of 1.2 × 1016 molecules cm−2 (77%) from 2019 to 2020. This could not be fully explained by meteorological conditions, further proving the role of lockdown on ambient NO2. Following Wuhan, other cities in China, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, also established restrictive lockdown measures before January 26. The deweathered reduction percent of NO2 in January for Guangzhou was comparable with that for Wuhan; however, the reductions for Beijing and Shanghai were much lower (Fig. 5b–d). This follows the conclusion put forth by Ding et al.40, who suggested no significant reductions of NOx emissions in Beijing in January 2020. A similar reduction trend for NO2 TVCDs was also observed by TROPOMI (Fig. S6).

Monthly TVCDs of NO2 in 2019 (red) and 2020 (green), and deweathered TVCDs of NO2 in 2019 (blue) in a Wuhan, b Beijing, c Shanghai, d Guangzhou, e Seoul, f Tokyo, g Milan, h Berlin, i Paris, j London, k New York, l New Delhi, and m Rio de Janeiro based on EMI observation. The black bars are the random retrieval errors.

Among the sources of NOx, lockdown measures first affected transportation, followed by industry. However, because basic living needs must be met, energy production should not be drastically reduced. Indeed, residential emissions may have increased because more people remain at home31. According to the emission inventory from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS)41, transportation contributed about 33% of the NOx emissions in Wuhan. Alone, this does not cover the reduction of NO2 in January, suggesting that most industries were also shut down, causing the reduction of NOx in Wuhan to reach an ultimate level without affecting basic living needs. Contrastingly, the decline in NO2 did not exceed the transportation contribution in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

In February 2020, lockdown measures were continuously implemented in China. During this period, NO2 concentrations across the four cities in China further decreased from those in January 2020; they were also significantly lower than those in February 2019. The largest reduction in the NO2 TVCDs still occurred in Wuhan. Because of the effective measures, the increase in COVID-19 infections dropped sharply in March 2020, and except for Wuhan, the lockdown was lifted in China. Since then, productivity and living activities in Wuhan have also gradually recovered. Therefore, NO2 concentrations in the four cities significantly increased from February to March 2020. However, the concentrations in the four cities remained approximately 30% lower than those in March 2019.

In February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic also spread across Korea and Japan, and the spread in Korea was noted to be faster than that in Japan. The Korean government placed restrictions to prevent the gathering of people and strengthen nucleic acid detection. The restriction measures caused a decrease in NO2 TVCD by 26% in Seoul when compared with the deweathered TVCD in February 2019 (Fig. 5e). In contrast, no lockdown measures were taken by Japan in February, suggesting a reason for the unaffected NO2 TVCD in Tokyo (Fig. 5f). The pandemic in Korea and Japan was further aggravated in March 2020. The NO2 TVCD in Seoul further decreased to 35% lower than the deweathered value in 2019, which is consistent with the decrease in surface NO2 concentration in this city42. In addition, owing to more stringent social distancing measures, the NO2 TVCD in Tokyo also sharply decreased.

In Europe, the COVID-19 pandemic first broke out in Italy in March 2020 and also reached its peak during that month. On March 10, the Italian government implemented strict measures to prevent gatherings. Corresponding to this period in March 2020, the recorded NO2 TVCD in Milan was 34% lower than that in March 2019, with meteorological corrections (Fig. 5g). EMI data was not available from April 2020, because of the failure in the solar battery of the Gaofen-5 satellite. Thus, after March 2020, we analyzed the changes in NO2 based on TROPOMI observations. The NO2 TVCD in Milan in April showed a declining trend because of continued lockdown (Fig. S6). In addition to column concentration, ground-level NO2 in this city also decreased by ~30% during the lockdown43. In the UK, Germany, and France, lockdown measures were issued from the middle and late March. The average NO2 TVCDs in Berlin and Paris in March 2020 significantly decreased compared with the deweathered TVCDs in March 2019, but the reduction percentage was much lower than that for Milan (Fig. 5h–i). However, because of the later implementation of lockdown measures in the UK, the deweathered reduction percent of NO2 TVCD in London in March was less than 10% (Fig. 5j). Surface observation in the UK also showed a more gradual decline of NO2 early in the outbreak of COVID-19 when compared to the sudden decline in the other European countries6. Apart from Italy, the other three European countries faced increasing detected infections of COVID-19 in April. The NO2 TVCDs with meteorological corrections in London and Paris during this month decreased by 38% and 48%, respectively. This indicated that restriction measures in both cities were strictly implemented in April, although the pandemic had broken and the lockdown measures had been established in March. During this month, the reduction in Paris even exceeded the contribution of transportation.

In the US, the pandemic broke out in March and then rapidly spread until June; lockdown measures were taken from late March. Correspondingly, NO2 TVCD decreased by 40% compared with the deweathered TVCD in March 2019 (Fig. 5k), which was slightly higher than the contribution of transportation. However, these measures were not mandatory, and gradually loosened until they were entirely relieved. As such, the NO2 TVCDs showed no evident reduction after April (Fig. S6).

In India and Brazil, the COVID-19 pandemic struck in March 2020 and broke out in April; lockdown measures were implemented from late March. In March 2020, NO2 TVCD decreased by 32% and 19% in New Delhi and Rio de Janeiro, respectively, when compared with the deweathered TVCDs in March 2019 (Fig. 4l–m). However, to recover the economy, the lockdown measures were gradually released from late May despite the more severe pandemic. Therefore, the NO2 TVCDs in both cities in June recovered to comparable levels in the corresponding month of 2019 (Fig. S6).

HCHO change indicates the relative importance of anthropogenic and natural sources of VOCs

The COVID-19 pandemic has been suggested to abate anthropogenic emissions of VOCs but not biogenic emissions. Therefore, changes in HCHO can indicate whether the VOCs in a city mainly originate from anthropogenic or biogenic sources. Monthly HCHO TVCDs from EMI observations in Wuhan from January to March 2020 were significantly lower than those in the corresponding months of 2019, with the maximum reduction seen in February (Figs. 6 and S7). Though Wuhan was very often covered by clouds in February 2019, which led to less spatial sampling and larger random error of HCHO TVCD than that in February 2020, the errors did not exceed the variations in HCHO TVCDs. A similar phenomenon was observed in Guangzhou and Shanghai. This suggests that anthropogenic emissions are a major source of VOCs and were substantially affected in these three cities. Lower HCHO yields from NMHC with NOx emission plunges may also reduce HCHO TVCDs9. However, the HCHO TVCDs in Beijing in January and March 2020 were even higher than those during the corresponding periods of 2019, and the decrease in HCHO TVCDs in February was close to the random retrieval errors. This may be explainable as enterprises with high VOC emissions (e.g., chemical plants) were moved to Hebei Province in 2014 to improve air quality in Beijing. As such, it can be assumed that most VOCs in Beijing originates from biogenic emissions, which were not disturbed by the pandemic.

Similar to Fig. 5, but for HCHO.

HCHO in the cities of the other investigated countries also showed different trends. In Milan, Berlin, and London, HCHO only presented a significant decrease in the first one or two months after the pandemic broke out but remained at comparable levels following this, with the random retrieval errors being considered (Figs. 6 and S7). One reason for this phenomenon is that the contribution of VOCs from biogenic sources is likely to have increased with an increase in temperature from winter to spring. HCHO in Tokyo and Rio de Janeiro decreased synchronously with NO2 at the beginning of lockdown, but the reduction percentage was lower than that of NO2 in the following months. In Seoul, the reduction in HCHO levels was comparable to that in NO2 levels; however, in New Delhi, no evident reduction in HCHO levels was observed. It should be considered, however, that various complex sources can cause distinct variations in HCHO levels. For instance, Sun et al.9 reported that the HCHO trends in Australia, northeastern Myanmar of Southeast Asia, Central Africa, and Central America were dominated by fire activities during the pandemic.

Discussion

The attenuation of anthropogenic activities during the pandemic caused a decline in both gross domestic product (GDP) and air pollutant emissions. Here, we use the ratio of quarterly averaged NO2 TVCD to the quarterly GDP in a country (NO2/GDP) to indirectly reflect NO2 emissions per unit GDP. As NOx emissions are mainly from the secondary industry, such as manufacturing and mining, the convergence between the variations of GDP and NO2 TVCDs can reveal whether the decline in GDP was mainly from the secondary industry, or the primary and tertiary industries, such as agriculture and service trade. To compare the changes in NO2/GDP in different countries, we calculated the relative variation of NO2 to GDP (△(NO2/GDP)) as follows:

Here, NO2 TVCD2020 is the quarterly averaged NO2 TVCD in 2020, and NO2 TVCDdeweathered 2019 is the deweathered quarterly NO2 TVCD in 2019. GDP2019 and GDP2020 are quarterly data for 2019 and 2020, respectively.

In the first quarter of 2020, the GDP in eight of the ten investigated countries, except for India and Japan, significantly decreased. Quarterly NO2 TVCDs decreased in the three developing countries, China, India, and Brazil, but increased in the other seven countries despite a substantial reduction in March. In China, △(NO2/GDP) was below 0, indicating that the reduction percent of NO2 TVCD was more than GDP, therefore suggesting that the secondary industry was more affected by the pandemic (Fig. 7). The higher NO2/GDP values in the remaining seven countries suggested that the decline in GDP was caused primarily due to impacts on the primary and tertiary industries. As such, this study proves that Chinese satellite instruments can play an important role in the global monitoring of atmospheric environmental events.

Materials and methods

TROPOMI data

TVCDs of NO2 and HCHO from TROPOMI were also used in this study. TROPOMI onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor (S-5P) was launched in October 2017. It measures ultraviolet and visible backscattered radiances from 266 to 775 nm, with a spectral resolution of 0.5 nm. The nadir spatial resolution of TROPOMI was 7 × 3.5 km2 which was then, improved to 3.5 × 5.5 km2 after August 201944. The data from TROPOMI was directly accessed via the Sentinel-5P Pre-Operations Data Hub website.

Correction of meteorological influence using GEOS-Chem Modeling

The GEOS-Chem model, a global 3-D chemical transport model (CTM), was used to deduce the influence of meteorology on air pollutant concentrations by simulating the change in air pollutants from 2019 to 2020. This model is driven by the Goddard Earth Observing System (GEOS) assimilated meteorological fields from the NASA Global Modeling and Assimilation Office45. The model includes a detailed mechanism of the universal tropospheric-stratospheric chemistry extension (UCX) mechanism46. Further, global anthropogenic and biofuel emissions from the CEDS inventory41 were used and processed through the Harvard-NASA emission component (HEMCO)47. NO2, SO2, and HCHO in 2019 and 2020 were simulated using the same inventory and their respective meteorological fields in different years. The observed TVCDs of these pollutants in 2019 were adjusted to those under the meteorological conditions in 2020 (TVCDdeweathered 2019) as follows:

Here, TVCDobs 2019 is the observed TVCDs from satellite instruments in 2019, and TVCDmodeling 2019 and TVCDmodeling 2020 are the simulated TVCDs from GEOS-Chem for the years of 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Data availability

The EMI level 1 and NO2, SO2, and HCHO datasets are available from Cheng Liu (chliu81@ustc.edu.cn) and Qihou Hu (qhhu@aiofm.ac.cn) upon reasonable request. The TROPOMI NO2 and HCHO datasets are available from https://s5phub.copernicus.eu/dhus/#/home.

References

Le Quéré, C. et al. Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 647–653 (2020).

Wang, Y. C. et al. Changes in air quality related to the control of coronavirus in China: Implications for traffic and industrial emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 731, 139133 (2020).

Bauwens, M. et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on NO2 pollution assessed using TROPOMI and OMI observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087978 (2020).

Liu, F. et al. Abrupt decline in tropospheric nitrogen dioxide over China after the outbreak of COVID-19. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc2992 (2020).

Zangari, S. et al. Air quality changes in New York City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 742, 140496 (2020).

Shi, Z. B. et al. Abrupt but smaller than expected changes in surface air quality attributable to COVID-19 lockdowns. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6696 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Enhanced secondary pollution offset reduction of primary emissions during COVID-19 lockdown in China. Natl Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa137 (2020).

Menut, L. et al. Impact of lockdown measures to combat Covid-19 on air quality over western Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 741, 140426 (2020).

Sun, W. F. et al. Global significant changes in formaldehyde (HCHO) columns observed from space at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091265 (2021).

Zhang, C. X. et al. First observation of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide from the Environmental Trace Gases Monitoring Instrument onboard the GaoFen-5 satellite. Light. Sci. Appl. 9, 66 (2020).

Xia, C. Z. et al. First sulfur dioxide observations from the environmental trace gases monitoring instrument (EMI) onboard the GeoFen-5 satellite. Sci. Bull. 66, 969–973 (2021).

Boersma, K. F. et al. Improving algorithms and uncertainty estimates for satellite NO2 retrievals: results from the quality assurance for the essential climate variables (QA4ECV) project. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 6651–6678 (2018).

Beirle, S. et al. The STRatospheric Estimation Algorithm from Mainz (STREAM): estimating stratospheric NO2 from nadir-viewing satellites by weighted convolution. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 9, 2753–2779 (2016).

Su, W. J. et al. An improved TROPOMI tropospheric HCHO retrieval over China. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 6271–6292 (2020).

Abad, G. G. et al. Updated Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Ozone Monitoring Instrument (SAO OMI) formaldehyde retrieval. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 19–32 (2015).

Abad, G. G. et al. Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Ozone Mapping and Profiler Suite (SAO OMPS) formaldehyde retrieval. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 9, 2797–2812 (2016).

Xia, C. Z. et al. Improved anthropogenic SO2 retrieval from high-spatial-resolution satellite and its application during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 11538–11548 (2021).

Su, W. J. et al. First global observation of tropospheric formaldehyde from Chinese GaoFen-5 satellite: locating source of volatile organic compounds. Environ. Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118691 (2021).

De Smedt, I. et al. Algorithm theoretical baseline for formaldehyde retrievals from S5P TROPOMI and from the QA4ECV project. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 11, 2395–2426 (2018).

Vigouroux, C. et al. TROPOMI-Sentinel-5 Precursor formaldehyde validation using an extensive network of ground-based Fourier-transform infrared stations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 3751–3767 (2020).

Xia, C. Z. et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of the Sentinel-5 Precursor operational SO2 products over China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 65, 2106–2111 (2020).

Ohara, T. et al. An Asian emission inventory of anthropogenic emission sources for the period 1980-2020. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4419–4444 (2007).

Zhao, B. et al. NOx emissions in China: historical trends and future perspectives. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 9869–9897 (2013).

Liu, F. et al. NOx emission trends over Chinese cities estimated from OMI observations during 2005 to 2015. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 9261–9275 (2017).

Levelt, P. F. et al. The Ozone Monitoring Instrument: overview of 14 years in space. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 5699–5745 (2018).

Chin, M. et al. Atmospheric sulfur cycle simulated in the global model GOCART: model description and global properties. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 105, 24671–24687 (2000).

Kharol, S. K. et al. Ceramic industry at Morbi as a large source of SO2 emissions in India. Atmos. Environ. 223, 117243 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Air pollutant emissions from coal-fired power plants in China over the past two decades. Sci. Total Environ. 741, 140326 (2020).

McLinden, C. A. et al. Space-based detection of missing sulfur dioxide sources of global air pollution. Nat. Geosci. 9, 496–500 (2016).

Zhang, Z. J. et al. Unprecedented temporary reduction in global air pollution associated with COVID-19 forced confinement: a continental and city scale analysis. Remote Sens. 12, 2420 (2020).

Shi, X. Q. & Brasseur, G. P. The response in air quality to the reduction of Chinese economic activities during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088070 (2020).

Sillman, S. The use of NOy, H2O2, and HNO3 as indicators for ozone-NOx-hydrocarbon sensitivity in urban locations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 100, 14175–14188 (1995).

Schroeder, J. R. et al. New insights into the column CH2O/NO2 ratio as an indicator of near-surface ozone sensitivity. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 8885–8907 (2017).

Lee, M. et al. Hydrogen peroxide, organic hydroperoxide, and formaldehyde as primary pollutants from biomass burning. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 102, 1301–1309 (1997).

Kean, A. J. et al. On-road measurement of carbonyls in California light-duty vehicle emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 4198–4204 (2001).

Wang, Q. et al. Emission factors of gaseous carbonaceous species from residential combustion of coal and crop residue briquettes. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 7, 66–76 (2013).

Curci, G. et al. Estimating European volatile organic compound emissions using satellite observations of formaldehyde from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 11501–11517 (2010).

Souri, A. H. et al. An inversion of NOx and non-methane volatile organic compound (NMVOC) emissions using satellite observations during the KORUS-AQ campaign and implications for surface ozone over East Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 9837–9854 (2020).

Zhu, L. et al. Anthropogenic emissions of highly reactive volatile organic compounds in eastern Texas inferred from oversampling of satellite (OMI) measurements of HCHO columns. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 114004 (2014).

Ding, J. et al. NOx emissions reduction and rebound in China due to the COVID-19 crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL089912 (2020).

Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 369–408 (2018).

Ju, M. J., Oh, J. & Choi, Y. H. Changes in air pollution levels after COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 750, 141521 (2021).

Putaud, J.-P. et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on air pollution at regional and urban background sites in northern Italy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 7597–7609 (2021).

Liu, M. Y. et al. A new TROPOMI product for tropospheric NO2 columns over East Asia with explicit aerosol corrections. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 13, 4247–4259 (2020).

Bey, I. et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 23073–23095 (2001).

Eastham, S. D., Weisenstein, D. K. & Barrett, S. R. H. Development and evaluation of the unified tropospheric-stratospheric chemistry extension (UCX) for the global chemistry-transport model GEOS-Chem. Atmos. Environ. 89, 52–63 (2014).

Keller, C. A. et al. HEMCO v1.0: a versatile, ESMF-compliant component for calculating emissions in atmospheric models. Geosci. Model Dev. 7, 1409–1417 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA23020301), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC0213104 and 2017YFC0210002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41977184, 41941011, and 51778596), the Key Research and Development Project of Anhui Province (202104i07020002), the Major Projects of High Resolution Earth Observation Systems of National Science and Technology (05-Y30B01-9001-19/20-3), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (2021443), and the Young Talent Project of the Center for Excellence in Regional Atmospheric Environment, CAS (CERAE202004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L. and Q.H. designed and supervised the whole study. C.L., C.Z., C.X., and W.S. retrieved the satellite data. H.Y. ran the GEOS-Chem model. C.L., Q.H., H.Y., X.W., Y.X., and Z.Z. contributed to the data analysis. C.L. and Q.H. wrote the paper with inputs from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C., Hu, Q., Zhang, C. et al. First Chinese ultraviolet–visible hyperspectral satellite instrument implicating global air quality during the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Light Sci Appl 11, 28 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-00722-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-00722-x

This article is cited by

-

Needs and challenges of optical atmospheric monitoring on the background of carbon neutrality in China

Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering (2024)

-

Eliminating the interference of water for direct sensing of submerged plastics using hyperspectral near-infrared imager

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Recent Progress in Atmospheric Chemistry Research in China: Establishing a Theoretical Framework for the “Air Pollution Complex”

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2023)