Abstract

Background:

The prevalence of febrile seizures (FSs) and epilepsy are often reported to be higher in sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, several studies describe complex features of FSs as risk factors for the development of subsequent epilepsy.

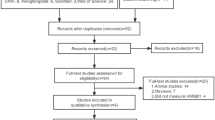

Methods:

During the period from 2002 to 2004 door-to-door studies with supplementary data collection were conducted in three different areas of Tanzania, examining the prevalence of FSs in 7,790 children between the age of 2 mo and 7 y at the time of the interview. The information on the presence of FSs of 14,583 children, who at the time of the interview were younger than 15 y, was collected in order to describe reported seizures, if any.

Results:

Overall, 160 children between 2 mo and 7 y with a prevalence rate of 20.5/1,000 (95% confidence interval: 17.5–23.9/1,000) met the criteria for FSs. The average age at onset was 2.2 (SD: 1.8) y and ~42% had complex FSs. Respiratory tract infections and malaria were the most frequent concomitant diseases.

Conclusion:

Our findings do not confirm the assumption of an increased prevalence of FSs in sub-Saharan Africa. However, the elevated number of complex FSs emphasizes the necessity of more reliable studies about FSs and its consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Febrile seizures (FSs) in children seem to occur frequently and often cause anxiety in parents. Prevalence rates from hospital- and community-based studies conducted up to now vary a lot according to the methods used, age definition and the country in which these studies were conducted (Supplementary Table S1 online). The majority of the studies estimate a prevalence of FSs in about 2–4% of all children (1,2,3). However, prevalence rates range from 9.9/1,000 ascertained in Germany (4) to 116.1/1,000 determined in a rural population in Nigeria (5).

Prevalence and incidence rates of FSs may be higher in regions of Asia and Africa, but epidemiological studies of low-income countries are scarce. Complex FSs have been reported to be more frequent in children in sub-Saharan Africa (6), and it is especially complex features, such as prolonged or focal seizures, that have been described as risk factors for the development of epilepsy (7,8,9) and may be related to the reported higher prevalence of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa (10,11). Furthermore, FS associated infectious diseases seems to be different in children with FSs in sub-Saharan Africa compared to the disease spectrum in the western world and management of those diseases such as malaria has to be taken into account when dealing with FSs in low-income countries (12).

This door-to-door study in combination with complementary multisource data collection at hospitals and Mother and Child Health Centres (MCHs) was designed to ascertain the community-based prevalence of FSs, to describe the various clinical attributes and to assess special features of FSs in Tanzania.

Results

Prevalence of Febrile Seizures

The number of cases with FSs found via the different methods and the resulting prevalence rates referring to the children between 2 mo and 7 y at the time of interview have been summarized in Table 1 . In this age category, 7,790 children consisting of 3,857 boys and 3,933 girls who belong to the study region are divided up as follows: 2,497 of Haydom, 623 of Wasso, and 4,670 children of the Vigoi Ward.

Overall, 147 children fulfilled the given criteria for FSs within the door-to-door surveys. In summary, 147 children of 7,790 between 2 mo and 7 y had at least one FS, resulting in a point prevalence rate of 18.9/1,000 (95% confidence interval (CI): 16.0–22.1/1,000) and a male to female ratio of 1.04:1.

With the help of the additional methods, 14 children with FSs were identified via the MCH Haydom and the Hospital of Wasso ( Table 1 ).

After deducting one child listed twice, 160 children made up of 82 boys and 78 girls met the criteria for FSs in its entirety. Combining the data ascertained by the different methods, the overall prevalence rate is 20.5/1,000 (95% CI: 17.5–23.9/1,000, with a male to female ratio of 1.05:1 ( Table 1 ).

The FS prevalence of the children under the age of 15 y solely within the door-to-door studies is 15.2/1,000 (95% CI: 13.2–17.3; 221/14,583 children under the age of 15 y). Taking into account only the children whose ages lie above the cut-off age for FSs within the door-to-door surveys, the prevalence of FSs is 11.5/1,000 (95% CI: 8.9–14.5; 69/6,021 children between 7 and 14 y of age).

Features of Febrile Seizures

Overall, 221 children with FSs were identified through the three door-to-door studies when referring to the study population of below 15 y at the time of the interview. Of those 221 children, 157 children (Haydom 102, Wasso 22, Vigoi 33) or their respective parents consented to an interview with a specific in-depth questionnaire ( Tables 2 , 3 , and 4 ).

Reliable information about the age at onset was available from 151 children. The arithmetic average of the age at onset was 2.2 (SD: 1.8) y. In approximately two thirds of the cases, the first FS occurred within the first 2 y of life. Referring to the information of 129 children, more than half of the cases (57%) had their FSs in the first half of the year and 29% during the heavy raining seasons from February to April. Details concerning the place of where the FS happened were known from 261 seizures. Almost 85% of these FSs happened outside medical facilities, for example at home or on the road.

The number of FS episodes, known from 151 children, ranged from 1 to 14 episodes with a median at 1 episode. Fifty-seven of those (38%) had more than one FS episode. The median duration of a FS, referring to 221 seizures, was 10 min, ranging from 1 min to a maximum of 360 min. Information about the length of fever before the FS was available from 144 episodes, resulting in an average of 2.5 (SD: 2.9) d. Eighty-six percent of 264 seizures were self-limiting ( Table 2 ).

Sixty-one of 145 children (42%) with FSs had at least one complex feature. Thus, 3 children had focal seizures, 41 children had prolonged seizures and 1 of the children had a recurrent seizure. Five children had prolonged focal seizures and 11 had prolonged recurrent FSs. Detailed information about the complex FSs and its features is listed in Table 3 .

Thirty-two percent of them had a history of seizure disorders within their family, of which 54% affected first degree relatives.

Causes of the febrile illness were mainly respiratory tract infections (36%) and malaria (34%), followed by gastrointestinal symptoms in 19%. Malaria at time of the fever was ascertained in 64% of 163 performed blood smears. In 181 of 199 FSs episodes (91%), medical attention was sought at hospitals or medical dispensaries. Household remedies like tepid sponging (40%) and acetaminophen (43%) often were used to reduce the fever and traditional medicine was applied in 9% of the cases. In 37 (25%) of 146 cases, the children received no treatment ( Table 4 ).

Discussion

The overall point prevalence of 20.5/1,000 within the three study regions is in accordance with other studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. Supplementary Table S1 online provides an overview of published studies concerning the frequency of FSs: a hospital-based study from the Haydom Lutheran Hospital in Tanzania, which is part of the region of the present study, estimated a hospital incidence of 37.9/1,000 for children below the age of 10 y (6). In further African studies listed in the table, the higher prevalence rates range from 26.5/1,000 (13) to 116.1/1,000 (5), based on different methods. Comparing the highest indicated rates of 51/1,000 (14) in Europe, 48/1,000 (15) in America, and 83/1,000 (2) ascertained in Asia, there seems to be trend to higher prevalence of FSs in Asia and Africa which was not confirmed by our study. The low FS point prevalence of 18.9/1,000 (when children up to 7 y from door-to-door studies only were considered) was confirmed by a low prevalence of 11.5/1,000 of children aged between 7 and 14 y at the time of the interview, i.e., those who are above the cut-off age for the occurrence of FSs. In a large Danish population study, Vestergaard et al. did not detect an increased long-term mortality in children with FSs, only a small exceed in the first 2 y after complex FSs was apparent (16). In comparison, several studies conducted in developing countries determined a higher mortality rate in patients with FSs and the authors attribute this fact mainly to the concomitant diseases of FSs, for example bronchopneumonia infections (6,17). Assuming that the mortality in children with FSs is higher in developing countries, this fact may explain the lower than expected prevalence in our study; however, studies about mortality in FSs are scarce. The superstitious beliefs of several African tribes, for example the association of seizure disorders and FSs with demonic possession or spiritual forces, may have led to underreporting (18). And in fact especially among the Maasai tribe in the Arusha region, the willingness to give details on the occurrence of FSs was very limited in this study. It also has to be taken into account that some information, especially that of FSs from many years ago, may not have been accurately reflected.

As shown in Supplementary Table S1 online, the male to female ratios range from 1:1 (19) to 3.75:1 (20), indicating that male children may be more susceptible to FSs. Our balanced male to female ratio of 1.05:1 does not confirm this phenomenon. About two thirds of the children had their first FS within the first 2 y of life. This is in accordance with other studies, reporting an age peak in the second year of life (1,2). In this study, more than half of the cases occurred during the first half of the year, which includes the heavy raining seasons from February till May and thus entails a higher risk of malaria infection. Two studies from Japan (21) and Italy (22) also observed such a seasonal distribution for FSs in correlation with seasonal diseases.

A history of complex FSs was ascertained in 42% of our cases. In a British survey, Verity et al. determined complex convulsions in 20% of all cases (23). On the contrary, Winkler et al. found a high preponderance of complex FSs of 71% in a hospital-based study at Haydom Lutheran Hospital (6). These figures suggest that complex FSs may occur more frequently in sub-Saharan Africa. However, there is a possibility that the higher proportion of complex FSs in our community-based study may be due to recall bias and the fact that parents tend to remember grave seizures more readily compared to simple ones. In the current study, 38% of the children suffered from recurrent FS episodes. Overall, young age at onset, epilepsy or FSs in relatives and complex FSs seem to be significant risk factors for the occurrence of recurrent FS episodes (7,24). As complex attributes seem to repeat in children with recurrent FS episodes (25) and recurrences, amongst others, may conceivably implicate subsequent epilepsy (8,26), the need of preventing these recurrent FSs becomes apparent.

Since complex features, especially the prolonged types, seem to be associated with the development of epilepsy (7,8,9,27), this high percentage of complex features may be related to the reported higher prevalence of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa (10,11) in comparison to high-income nations (28). Beside complex attributes, the number of FS episodes, a positive family history of unprovoked seizures and neurological abnormality represent, inter alia, risk factors for subsequent epilepsy (3,8,29). In our study, we found a positive family history of seizures in nearly one third of the cases and also recurrent FS episodes occurred in more than one third of the children. However, the discussion as to whether FSs may favor the development of epilepsy is still controversial.

Detailed studies indicate that decreased birth weight, pre- and perinatal problems, prematurity as well as lower socioeconomic status, smoking and alcohol abuse during pregnancy represent possible risk factors for the emergence of FSs (29,30,31,32).

The cause and severity of the febrile illness loom large in the development of FSs, and it has to be taken into account that associated diseases in sub-Saharan Africa differ from those in high-income countries. Malaria, tuberculosis, influenza, and measles for instance, represent the common infectious and parasitic diseases in Africa region (33). A frequent appearance of FSs and febrile illnesses caused by influenza A virus (34), human herpes virus 6 (35), and respiratory tract infections (32) were determined in several studies. A study conducted at Haydom Lutheran Hospital in Tanzania identified malaria as one of the most frequent accompanying illness in children with FSs (36). This also applies to the current study, as we found respiratory tract infections and malaria as the leading presenting symptoms of the febrile illnesses, which is compatible with the aforementioned seasonal distribution.

According to our results, most of the seizures happened outside medical facilities. Lack of means of transportations and aggravating factors during the journey to the often distant healthcare facilities in this region emphasize that it is often impossible to receive appropriate medical help timely. Therefore, help is often sought by traditional healers instead of medical facilities (18). However, our study shows that in case of a FS, most of the parents attended medical facilities like hospitals or dispensaries. We also came to the conclusion that household remedies like tepid sponging and acetaminophen were, in the meanwhile, often used to reduce the fever and limit the seizure. Antipyretic drugs may lower the body temperature in febrile children, but several studies ascertained that there is no benefit of antipyretic drugs in preventing recurrent FSs (37,38). The guidelines composed by the International League against Epilepsy strongly recommend an acute therapy to prevent a febrile status epilepticus. This includes the registration of symptoms, prevention of aspiration or injuries and reduction of fever by the parents or other attendees. Furthermore, diazepam rectal in FSs with duration longer than 2–3 min and benzodiazepines or phenobarbital intravenous in case of prolonged FSs or status epilepticus (39).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study supports findings that the prevalence of FSs in sub-Saharan Africa may not be higher compared to high-income countries. However, the comparatively large share of complex FSs has implications and emphasizes the necessity of further studies into FSs in countries of sub-Saharan Africa. It is deemed important to expand the knowledge on FSs and its risk factors, and to improve medical care in low-income regions in order to prevent potential adverse neurological outcome such as epilepsy later in life.

Methods

The study took place during the period from 2002 to 2004 in the catchment area of Haydom Lutheran Hospital, Manyara region; Wasso Hospital, Arusha region; and Mahenge Hospital, Morogoro region, Tanzania. Three door-to-door surveys form the basis of this study and for the purpose of prevalence calculation two of those surveys (Haydom and Wasso) were complemented with supplementary retrospectively collected data from the study areas’ main hospitals and respective MCHs of the study region with the aim to achieve a near 100% case recruitment. For Mahenge hospital, no reliable supplementary data collection method could be identified so that prevalence calculation relies on data from the door-to-door study only.

Information Retrieval and Definitions

Within the door-to-door surveys, a team of three last-year medical students and translators interviewed the parents or relatives of the children from the three study regions by using a screening questionnaire. This questionnaire consisted of a case confirmation part for identifying children with FSs and a more specific part with detailed questions about the characteristics of the FSs (see Supplementary Table S2 online) and had already been validated in a previous hospital-based study (6). Cases of other seizure disorders (e.g., epilepsy) except FSs were excluded. With the help of translators the information was written down manually and was transcribed into Excel spreadsheets later. Double listed information between the door-to-door surveys and the additional methods were detected with the assistance of the parents and ten-cell-leaders (community leaders) as well as by comparing names and area of origin using Excel spreadsheets.

The following definitions were adhered to: FSs are defined as seizures occurring with a fever without obvious intracranial pathology in early childhood and are subdivided into simple and complex FSs, the latter being represented by seizures (i) lasting more than 15 min, (ii) occurring more than once within 24 h, and (iii) appearing with focal features (7,25). A FS duration of more than 30 min is defined as a status epilepticus and belongs to the category of complex FSs (40).

Setting and Recruitment

The data collection was conducted in three areas of Tanzania. The performance of the community-based studies depended largely on Tanzania’s administrative system that is subdivided into 26 regions consisting of various districts and divisions with subordinated wards, which in turn combine several villages. So-called “Ten-cells” represent the smallest administrative units within the village. Figure 1 shows a map of Tanzania with the three study locations: Haydom in northern Tanzania, Wasso near to the Kenyan border, and Vigoi (Mahenge) in southern Tanzania.

Map of Tanzania with the three study locations. Adapted with permission from d-maps.com (41).

Only children that were younger than 15 y at the time of the study were included into the study population. All subjects with known gender and exact age between 2 mo and 7 y at the time of interview were listed to assess the point prevalence of FSs in order to keep the recall bias for age to a minimum. For the prevalence calculation, the information of the door-to-door surveys was supplemented with that from other data sources, as described below. However, in-depth information on clinical characteristics of FSs was only ascertained within the door-to-door surveys and for that purpose data of all interviewed children of the study population irrespective of age was included.

For the door-to-door studies the nearer catchment area (closest villages within a radius of 5–10 km) of the three chosen hospitals ( Figure 1 ) was tackled. Hospitals were selected according to previously established working relationships between the principal investigator of the study (A.S.W.) and the hospital directors. The sampling unit was represented by the ten-cell, the smallest administrative unit in Tanzania. The ten-cell is overseen by a ten-cell leader who assured access to the study population. All households in one ten-cell were seen.

In Haydom, 12 villages belong to the nearer catchment area. Members of 1,458 households of randomly selected ten-cells (villages were widespread) were interviewed. In addition, all children attending the well-structured MCHs at Haydom Lutheran Hospital during that period were also surveyed.

In Wasso, four villages belong to the nearer catchment area of Wasso hospital. Members of 452 households of all ten-cells of these villages were seen. In addition, Wasso Hospital had a very good archiving system and all admissions between 2002 and 2004 were screened for febrile seizures.

In Mahenge, 11 villages belong to the nearer catchment area of Mahenge hospital. Members of 4,209 households of all ten-cells of these villages were seen. No additional methods of data acquisition such as MCH or hospital archive was deemed appropriate.

In the course of the overall door-to-door survey of all three sites, 81 individuals refused to give information or were absent, hence 14,583 children under the age of 15 y in 27 villages were included into the overall study population. Of these, 4,286 children belonged to Haydom, 967 to Wasso, and 9,330 to Vigoi catchment area. For the purpose of calculating the point prevalence of FSs, the information of 7,790 children in the age category between 2 mo and 7 y, which belong to the defined study region, was collected.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were entered and calculated within Excel spreadsheets. The 95% CI of the prevalence rates were calculated by using Fisher’s exact test. Most of the collected information about the clinical features relates to the summary of all FS episodes of one subject.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the National Institute of Medical Research and the Commission of Science and Technology in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all included children.

Statement of Financial Support

This work was supported by the Centre for International Migration (CIM), Frankfurt, Germany; the Savoy Epilepsy Foundation, Quebec, Canada; and third party funding from the University of Innsbruck.

Disclosure

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

Forsgren L, Sidenvall R, Blomquist HK, Heijbel J . A prospective incidence study of febrile convulsions. Acta Paediatr Scand 1990;79:550–7.

Tsuboi T . Epidemiology of febrile and afebrile convulsions in children in Japan. Neurology 1984;34:175–81.

Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH . Predictors of epilepsy in children who have experienced febrile seizures. N Engl J Med 1976;295:1029–33.

Doerfer J, Wässer S . An epidemiologic study of febrile seizures and epilepsy in children. Epilepsy Res 1987;1:149–51.

Iloeje SO . Febrile convulsions in a rural and an urban population. East Afr Med J 1991;68:43–51.

Winkler AS, Tluway A, Schmutzhard E . Febrile seizures in rural Tanzania: hospital-based incidence and clinical characteristics. J Trop Pediatr 2013;59:298–304.

Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH . Prognosis in children with febrile seizures. Pediatrics 1978;61:720–7.

Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Shirts SB, Kurland LT . Factors prognostic of unprovoked seizures after febrile convulsions. N Engl J Med 1987;316:493–8.

Verity CM, Golding J . Risk of epilepsy after febrile convulsions: a national cohort study. BMJ 1991;303:1373–6.

Preux PM, Druet-Cabanac M . Epidemiology and aetiology of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:21–31.

Winkler AS, Kerschbaumsteiner K, Stelzhammer B, Meindl M, Kaaya J, Schmutzhard E . Prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics of epilepsy–a community-based door-to-door study in northern Tanzania. Epilepsia 2009;50:2310–3.

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2013: World Health Organization, 2013. (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/81965/1/9789241564588_eng.pdf.)

Birbeck GL . Seizures in rural Zambia. Epilepsia 2000;41:277–81.

Baldin E, Ludvigsson P, Mixa O, Hesdorffer DC . Prevalence of recurrent symptoms and their association with epilepsy and febrile seizure in school-aged children: a community-based survey in Iceland. Epilepsy Behav 2012;23:315–9.

Rose SW, Penry JK, Markush RE, Radloff LA, Putnam PL . Prevalence of epilepsy in children. Epilepsia 1973;14:133–52.

Vestergaard M, Pedersen MG, Ostergaard JR, Pedersen CB, Olsen J, Christensen J . Death in children with febrile seizures: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2008;372:457–63.

Osuntokun BO . Convulsive disorders in Nigerians: the febrile convulsions. (An evalugtion of 155 patients). East Afr Med J 1969;46:385–94.

Ofovwe GE, Ibadin OM, Ofovwe EC, Okolo AA . Home management of febrile convulsion in an African population: a comparison of urban and rural mothers’ knowledge attitude and practice. J Neurol Sci 2002;200:49–52.

Piperidou HN, Heliopoulos IN, Maltezos ES, Stathopoulos GA, Milonas IA . Retrospective study of febrile seizures: subsequent electroencephalogram findings, unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in adolescents. J Int Med Res 2002;30:560–5.

Al Rajeh S, Awada A, Bademosi O, Ogunniyi A . The prevalence of epilepsy and other seizure disorders in an Arab population: a community-based study. Seizure 2001;10:410–4.

Tsuboi T, Okada S . Seasonal variation of febrile convulsion in Japan. Acta Neurol Scand 1984;69:285–92.

Manfredini R, Vergine G, Boari B, Faggioli R, Borgna-Pignatti C . Circadian and seasonal variation of first febrile seizures. J Pediatr 2004;145:838–9.

Verity CM, Butler NR, Golding J . Febrile convulsions in a national cohort followed up from birth. I–Prevalence and recurrence in the first five years of life. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:1307–10.

Knudsen FU . Recurrence risk after first febrile seizure and effect of short term diazepam prophylaxis. Arch Dis Child 1985;60:1045–9.

Berg AT, Shinnar S . Complex febrile seizures. Epilepsia 1996;37:126–33.

Berg AT, Shinnar S . Unprovoked seizures in children with febrile seizures: short-term outcome. Neurology 1996;47:562–8.

Matuja WB, Kilonzo G, Mbena P, et al. Risk factors for epilepsy in a rural area in Tanzania. A community-based case-control study. Neuroepidemiology 2001;20:242–7.

Forsgren L, Beghi E, Oun A, Sillanpää M . The epidemiology of epilepsy in Europe - a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2005;12:245–53.

Vestergaard M, Christensen J . Register-based studies on febrile seizures in Denmark. Brain Dev 2009;31:372–7.

Aydin A, Ergor A, Ozkan H . Effects of sociodemographic factors on febrile convulsion prevalence. Pediatr Int 2008;50:216–20.

Vahidnia F, Eskenazi B, Jewell N . Maternal smoking, alcohol drinking, and febrile convulsion. Seizure 2008;17:320–6.

Abd Ellatif F, El Garawany H . Risk factors of febrile seizures among preschool children in Alexandria. J Egypt Public Health Assoc 2002;77:159–72.

World Health Organization. Health Situation Analysis in the African Region, Atlas of Health Statistics, 2011. Brazzaville, Congo: World Health Organization, 2011.

Hara K, Tanabe T, Aomatsu T, et al. Febrile seizures associated with influenza A. Brain Dev 2007;29:30–8.

Millichap JG, Millichap JJ . Role of viral infections in the etiology of febrile seizures. Pediatr Neurol 2006;35:165–72.

Mosser P, Schmutzhard E, Winkler AS . The pattern of epileptic seizures in rural Tanzania. J Neurol Sci 2007;258:33–8.

Strengell T, Uhari M, Tarkka R, et al. Antipyretic agents for preventing recurrences of febrile seizures: randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:799–804.

Camfield PR, Camfield CS, Shapiro SH, Cummings C . The first febrile seizure–antipyretic instruction plus either phenobarbital or placebo to prevent recurrence. J Pediatr 1980;97:16–21.

Feucht M, Gruber-Sedlmayr U, Hauser E, Rauscher C . [Guidelines of the Austrian section of ILAE for (differential) diagnosis and treatment of febrile seizures]. Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Sektion der Internationalen Liga gegen Epilepsie 2005;5:12–5.

Commission on Epidemiology and Prognosis, International League Against Epilepsy. Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy. Epilepsia 1993;34:592–6.

Tanzania/Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania, boundaries, hydrography, main cities, main roads, names [map]. d-maps.com. (http://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=26272&lang=en.)

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the staff, students, translators and all other supporters of the three large studies. They are very much indebted to all the children and their parents who spared time to answer their lengthy protocol.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

(DOC 104 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Storz, C., Meindl, M., Matuja, W. et al. Community-based prevalence and clinical characteristics of febrile seizures in Tanzania. Pediatr Res 77, 591–596 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.3

This article is cited by

-

The baseline risk of multiple febrile seizures in the same febrile illness: a meta-analysis

European Journal of Pediatrics (2022)

-

Prevalence, risk factors and behavioural and emotional comorbidity of acute seizures in young Kenyan children: a population-based study

BMC Medicine (2018)