Abstract

Approximately 2.3 million children in the United States live separately from both parents; 70–90% of those children live with a relative. Compared with children living with one or both parents, children in nonparental care are in poorer health, are at heightened risk for experiencing disruptions and instability in caregiving, and are vulnerable to other social antecedents of child health (e.g., neglect, poverty, maltreatment). Given the significant impact of adversity in childhood on health across the lifespan, which is increased among children in nonparental care, it is informative to consider the health risks of children living in nonparental care specifically. Research examining the contributions of poverty, instability, child maltreatment, and living in nonparental care, including meta-analyses of existing studies, are warranted. Longitudinal studies describing pathways into and out of nonparental care and the course of health throughout those experiences are also needed. Despite these identified gaps, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that attention to household structure is not only relevant but also essential for the clinical care of children and may aid in identifying youth at risk for developing poor health across the lifespan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The percentage of children living separately from both parents declined from 6% in 1880 to 3% in 1970; however, since 1970, rates have increased (1). Approximately 22.4 million US children live separately from at least one parent, and 2.3 million children live separately from both parents (1,2,3). Among children living separately from both parents, between 70 and 90% live with a relative (1,4). It is estimated that the majority (55%) of children in nonparental care live with grandparents; the remainder live with other relatives (22%), nonrelatives (9%), foster caregivers (9%), or on their own (1%).

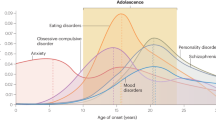

Children generally live with nonparental caregivers for one of three broadly defined reasons: the parent is a threat to the safety of the child (e.g., child welfare involvement), the parent is unavailable (e.g., incarceration, deployment, death), or the parent is lacking resources to care for the child (e.g., child lives with grandparent to access better school services) (2). As is depicted in Figure 1 , ~1.3 million children live in private kinship care, where children are cared for by relatives (87% by grandparents) without any child welfare involvement (5,6,7). An estimated 300,000 children live in voluntary kinship care (2), where child welfare agencies remove children from parental care and place them with relatives, but the parent or nonparental caregiver maintains legal custody of the child (5,7). Fewer (~200,000) children are in kinship foster care, where child welfare agencies take legal custody of children and place them with relatives. Unlike private kinship care, less than half (43%) of children in kinship foster care live with grandparents (5,6,7). Roughly 400,000 children live in formal foster care, where children are placed with licensed foster caregivers—typically nonrelatives (8). The remaining children in nonparental care reside in a variety of other living arrangements (e.g., living with a family friend, step-parents in the absence of a parent, institutional settings, living as head of household; 2).

Frequencies of nonparental care by type of arrangement and relationship to the child.

The Health of Children in Nonparental Care

Compared to children living with parents, children in nonparental care are in poorer health (3). According to data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, nonparental caregivers are less likely to report that children in their care are in good or very good physical or mental health compared to children living with at least one parent (3). Those data further suggest that children in nonparental care are more likely to have a special healthcare need, including mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and disruptive behaviors (3). Similarly, in their review of the literature, Vandivere et al. (2) found that across studies of grandparents as primary caretakers, children in the care of grandparents without a parent present experience higher rates of asthma, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, behavior problems, depression, and developmental delays/disabilities compared with children living with at least one parent. Likewise, Dubowitz et al. (9) conducted chart reviews of children entering kinship care and reported that 90% of those children had at least one health problem, 39% had three or more health problems, and more than half (53%) were in need of medical treatment. The most frequent health issues identified among children entering kinship care were behavior problems, dental problems, asthma, skin conditions, and obesity (9). A secondary analysis of data from the National Survey of America’s Families indicated that children in kinship care experienced increased emotional problems, poorer health, and physical conditions that limited their abilities more frequently than their peers living with parents (10). Behavior problems persist well into adolescence; in a secondary analysis of the National Survey of Family Growth comparing young women who had lived apart from their parents to those who had not, women previously in nonparental care reported increased sexual risk behaviors compared to young women living with at least one parent, including engaging in voluntary sexual intercourse at younger ages, first pregnancy at younger ages, and more sexual partners (11). There is indication that at least some of these effects persist into adulthood. Among adult women participating in the National Survey of Family Growth who had lived with nonparental relative caregivers as children, researchers found increased anxiety and unhappiness with life as adults, but no difference in physical health compared with women who had lived with at least one parent throughout childhood (12).

There is also reported variability in health among children living in differing subtypes of nonparental care arrangements. In their review of 6 mo of administrative child welfare data from a large urban county in Minnesota, Beeman et al. (13) reported that children in kinship foster care were significantly less likely to have a disability or special healthcare need at time of placement when compared with children in formal foster care, indicating that there may be existing differences between these groups. Likewise, analysis of National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing data indicates that significantly more children in foster care (42.1%) compared to voluntary kinship care (32.8%) have abnormal behavior at time of placement, use prescriptions medications (3.2 vs. 0.6%), and access mental health services (35.4 vs. 24.3%; (14)). Mental health problems are also reported more frequently by formal foster caregivers than by voluntary kinship and kinship foster caregivers and do not appear to be explained by differences in rates of poverty and other social capital resources between kinship and nonkinship caregivers (15,16). Among kinship caregiver arrangements, health status differences are also seen based on the degree of children’s services involvement. One review reported that roughly half (51%) of children in voluntary kinship care (i.e., where children’s services was involved with placement) experience mental health problems, compared with 43% of children in private kinship care (where no children’s services involvement occurred; 6).

In addition to health status, access to health insurance and financial assistance also vary by type of nonparental care arrangement, which has a direct impact on child health and access to healthcare. Only children in formal foster care are typically eligible for foster care maintenance payments. Youth in kinship and formal foster care automatically qualify for Medicaid, but children in other living arrangements only qualify for those benefits if the income of the family they live with meets the eligibility criteria (5,6). Children in private kinship care (i.e., without child welfare involvement) are significantly less likely to receive any insurance (including public insurance) and are also less likely to be in fair or poor health (6).

Poverty, Nonparental Care, and Health

Collectively, the literature on children living apart from their parents indicates that 66% of children are racial and ethnic minorities and 40% live in households with income below poverty level (3,5). In the United States, poverty is typically defined using gross household income and the number of individuals in the household (17). Rates of poverty are of particular concern for children living with grandparents. Grandparents serving as sole caregivers have significantly lower educational attainment as well as lower rates of employment, income, and insurance access compared with other households (18). The implications of poverty reach beyond financial resources to include access to services and benefits, social capital, and educational opportunities (19). Consistently across studies, results indicate that growing up in impoverished environments is detrimental (19,20). This includes premature mortality (20), worse cardiovascular health (21), declines in mental health (22), increased mobility impairments (23), and poor immune system function (24). The pathways linking poverty to adult health have been described and involve biological (e.g., physiological impact of poverty) and behavioral (e.g., engaging in negative health behaviors such as smoking) factors (19,20,24,25,26,27,28). While more research on the appropriate interventions to address these mechanisms is needed (29), research to date does indicate that providing services to address poverty in childhood does contribute to improved outcomes (19). Importantly, when healthcare providers are able to effectively identify the socio-environmental factors (including poverty) that place a child at risk for poor health outcomes, providers can effectively connect families to services that address those needs (30). Such interventions often need to target parenting behaviors known to be associated with poverty (29); whether changing caregivers addresses some of these issues for children entering nonparental care is not well understood. Attention to who the caregiver is and the household structure of the child is critical for understanding the complex interplay of the environment, child development, and health and well-being (31). As children in nonparental care are at higher risk for poverty, identification and risk assessment of household structure is imperative to determine possible therapeutic interventions.

Instability, Nonparental Care, and Health

While ~30% of children live apart from both parents for 3 or more years (32), one-third of living arrangements away from parents last less than 2 y (33). Thus, children who are in the care of nonparental caregivers are at heightened risk for experiencing subsequent disruptions and instability. Many nonparental care arrangements are temporary and fluctuate within a short period of time, making it challenging to identify and to follow children in nonparental care longitudinally (3). As is the case with poverty, disruptions in caregiving are also known to be associated with poorer health outcomes (34,35,36). The majority of studies describing stability of nonparental care arrangements has been among children in foster care and suggests that more than half of children in foster care experience at least one placement change and more than one-third experience two or more placement changes while in foster care (37,38,39). Annual rates of placement change across children in foster care are estimated to be between 0.55 and 0.62, with some children changing placements multiple times per year (40,41). Placement instability has been associated with hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation (42), internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (43,44), and increased emergency department use (38). Notably, these increased negative symptoms and behaviors appear to contribute to placement instability as well (43).

Children living with relative caregivers tend to experience more stability in living arrangements than children in formal foster care (13). While stability is generally thought to be a protective factor, one 6-year prospective study of teens in a large US county found that among teens living with kinship caregivers, longer duration in nonparental care was associated with increased adolescent sexual risk behaviors, substance use, self-destructive behaviors, behavior problems, and trauma symptoms (15). These findings suggest that, at least in some instances, there is an incremental effect of time living apart from parents on health. The underlying cause of children living separately from parents (e.g., child welfare involvement, length of parental incarceration) or placement disruptions associated with increased time in nonparental care may be contributing to poor health in children as well.

Adversity, Nonparental Care, and Health

For an estimated 900,000 children, living with nonparental caregivers is the result of identified child maltreatment and subsequent involvement with child protective services (5). Children who experience adversity or are the victims of maltreatment (45) have poorer physical and mental health when compared with children in the general population and with Medicaid-eligible children (46,47). Among children entering foster care, 60–85% demonstrate physical, developmental, or mental health needs (48). The most common physical health issues include dermatologic issues, respiratory issues, and dental issues (48). Developmental delays are very prevalent, found in almost 50% of children entering foster care (49). Physical health problems and developmental delays are disproportionally noted in children less than 6 y of age (49,50). Mental health diagnoses are not common among children entering foster care (50), but symptoms of mental health diagnoses, including behavioral problems, are often present at time of placement and diagnoses frequently follow entry into care (51). These physical and mental health problems are compounded if services are not provided in a timely and effective manner (52).

As noted previously, the majority of children in nonparental care arrangements are not involved with child welfare (i.e., private kinship care); thus, these families are not represented in many of the findings from national surveys (e.g., National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing and Consortium of Longitudinal Studies in Child Abuse and Neglect; (53, 54)). However, The National Survey of Children in Nonparental Care (NSCNC) (3), an extension of the 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health (55), asked extensive questions to assist with identifying and surveying a nationally representative sample of nonparental caregivers’ reports of the health and living situations of children aged 0–16 y. Findings from that survey indicate that children living without parental caregivers have experienced adversity at much higher rates than that of their peers who live with one or more parents (3). Specifically, 30% of youth in nonparental care have experienced four or more adverse life events, compared with 14% of children living with one parent and 1% of children living with two parents. Neighborhood and caregiver violence, incarceration, mental illness, and substance use are the most common adverse experiences for youth in nonparental care.

These adverse experiences contribute to poor health outcomes, as demonstrated by Felitti et al. (56), whose work showed that adverse childhood events have cumulative associations with long-term adult outcomes, including heart disease, liver disease, substance abuse, depression, and suicide attempts. This research has been replicated in young children; in childhood, the negative impact of adverse childhood experiences includes increased risk of behavioral problems (57), developmental delays (58), and school failure (59). Due to elevated rates of poverty, maltreatment, and adverse experiences among children in nonparental care, understanding household structure may be an important clue toward identifying and ultimately reducing these associated health risks.

The Interplay Between Nonparental Care and Social Antecedents of Child Health

Nonparental care often co-occurs with poverty, instability in caregiving, and adversity (2,19). Few studies have attempted to estimate these contributions separately, and when they do findings have been mixed (60). Findings from National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing indicate that there are no differences in cognitive functioning, internalizing, or externalizing behavior problems for children in nonparental care after poverty and maltreatment were accounted for, suggesting that nonparental care has no direct effect on child health (61). Other studies have found significant interaction effects between nonparental care, poverty, and maltreatment in predicting health outcomes (62). Specifically, children cared for by relatives who also live in poverty were found to experience worse outcomes compared to children living with relatives who have higher incomes, but both groups fared worse than children living with at least one parent (10).

To more closely examine these associations across all types of nonparental care arrangements, we analyzed data from the NSCNC (3) with the goal of better understanding the unique effects of poverty, maltreatment, instability, and type of nonparental caregiver on seven dichotomous indicators of child health assessed in the NSCNC: child mental health services, hearing, vision, concentration/attention, mobility, activities of daily living, and independence in the community. Our analytic model was consistent with the theoretical model depicted in Figure 2 . That model, adapted from the research reviewed above, suggests that the health status of children in nonparental care is impacted by existing genetic/biological risks, environmental risks, and the complex processes by which children enter nonparental care arrangements. Specifically, while many factors contribute to entry into nonparental care, the three key contributors previously identified in the literature are poverty, parent availability, and safety. Once children are in nonparental care arrangements, there is ongoing risk for placement instability, maltreatment, and poverty, which also contributes to child health outcomes. Using the NSCNC, we analyzed cross-sectional data examining the associations among history of poverty, current poverty, placement instability, history of maltreatment, and demographic characteristics in relation to indicators of child health. Analyses were completed using Mplus 7.2 (63) to allow for the estimation of multiple logistic regression models simultaneously. Sample weights were used to ensure that findings reflected the population of children in nonparental care. Maximum likelihood estimation with robust SEs was used to account for missing data. Our results are summarized in Table 1 . Findings indicate distinct patterns for physical health (i.e., hearing, vision, mobility, activities of daily living) compared to mental health and functioning (i.e., receiving therapy, attention, and concentration). Specifically, few caregivers endorsed having children who experienced physical health indicators, and as a result, few demographics and social antecedents were associated with these outcomes. For vision, an increase in the time children were in their current placement was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of having vision impairments (B = 4.31; P < 0.01), likely indicating that children with vision impairments enter into nonparental care arrangements at younger ages. No other meaningful effects were identified for physical health indicators. However, for mental health indicators, a variety of contributing factors were statistically significant with robust odds ratios (ORs). Girls were nine times more likely to have received therapy in the 12 mo prior to the NSCNC survey when compared to boys. Caregivers who expected children to experience another placement disruption, who reported that children were not with them the majority of the week, and who reported that children had spent a month or more living away from them after initially moving in were also significantly more likely to report children receiving therapy (OR = 12.67, 6.75, and 7.25, respectively). With regard to attention and concentration, caregivers are much more likely to report problems when the caregiver is a grandparent or a formal foster caregiver compared to other caregivers (OR = 6.02 and 5.41, respectively). Finally, caregivers who report that the child has spent a month or more living apart from them since placement also endorse more attention issues (OR = 6.86) as do caregivers who are caring for child victims of maltreatment (OR = 3.28).

Social antecedents of nonparental care and their contributions to child health.

When our findings are considered within the context of other studies addressing the health of youth in nonparental care, three distinct themes emerge. First, health concerns appear to be fairly pervasive among children in nonparental care, with a particular risk for mental health issues. In this survey, 30% of caregivers reported that the child in their care had received mental health treatment in the previous 12 mo, and 20% reported that children had difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions. Children in foster homes and under the care of grandparents were particularly at risk. Future studies should consider combining the NSCNC with the National Survey of Children’s Health to examine these associations with more sophisticated indicators of child health. Second, our findings reiterate the complexities of social antecedents that contribute to child health, and the heterogeneity in those mechanisms. Specifically, these results demonstrate that for mental health services, disruptions in caregiving—either previously or anticipated—were associated with the child having accessed mental health services the previous year. In contrast, difficulty with attention was associated with both disruptions in living arrangements and a history of maltreatment. Finally, these findings indicate particular vulnerability associated with increased length of time in nonparental care and decreased stability in nonparental care arrangements for both physical and mental health concerns. Importantly, these are cross-sectional associations, so causal direction cannot be inferred. While more research is needed, findings point to nonparental care status as a clear indicator of risk for poor health outcomes. Given that an estimated 2.3 million children in the United States are living in nonparental care (4), it is critical that clinicians and researchers alike understand and account for household structure and caregiving as part of their work. This begins with ensuring that those working in the healthcare system understand the types of living arrangements and identify a child’s custody status and household structure at each patient/research encounter.

For clinicians, it is imperative to recognize that children living in nonparental care may require more intensive health services (64). This may include facilitating record gathering and record review, providing developmental, educational, and mental healthcare screenings and service referrals, enhanced anticipatory guidance and education for nonparental caregivers, and multidisciplinary collaboration with all stakeholders involved in the care of the child (i.e., child welfare; 65)

For researchers, there are several gaps in the literature on children in nonparental care that should be addressed. First, there is currently only one publication of findings from the NSCNC (3,55), and further examination of that cross-sectional data is warranted. Second, longitudinal studies following children as they transition in and out of nonparental care are needed to better understand the long-term impact of nonparental care on child health. Third, a better understanding of the impact of fluctuations in living in nonparental care is needed. Some studies have addressed stability in foster care specifically (43,66), but that work has had limited extension to other nonparental care arrangements. Additionally, research (and assessments of household structure more generally) often assumes that children are primarily dwelling in one household at a time. Work that examines the tempo of changes in children’s households (i.e., living with parents on the weekend, nonparental caregivers during the week; shifting from one household to another on alternating weeks) has primarily been examined for children of divorce (67,68,69). Extending such studies to the population of children living in nonparental care, particularly private and voluntary kinship care, would provide better insight into how children are living within various family units and the implications of those arrangements on their health and well-being over time.

Conclusions

In summary, children living separately from both parents are, in general, at a disadvantage with regard to indicators of physical health, mental health, and access to healthcare. The mechanisms by which living in nonparental care appear to influence health include exposure to poverty, adverse childhood experiences, maltreatment, instability and disruptions in caregiving, and access to health insurance and public assistance. These facets of the nonparental care experience are more pronounced in some nonparental care arrangements compared with others. More research examining these mechanisms is warranted to detect patterns in relations among correlates of nonparental care and nonparental care and heath. Longitudinal studies describing the pathways into and out of nonparental care and the course of health are also needed. Despite these identified gaps, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that attention to household structure is relevant and necessary for the clinical care of children and may aid in identifying youth at risk for developing poor health across the lifespan.

Statement of Financial Support

No financial assistance was received in support of this review paper.

References

Kreider RM, Ellis R. Living Arrangements of Children, 2009. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau, 2011:1–26.

Vandivere S, Yrausquin A, Allen T, Malm K, McKlindon A Children in Nonparental Care: A Review of the Literature and Analysis of Data Gaps. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2012:1–46.

Bramet MD, Radel LF. Children in Nonparental Care: Findings From the 2011–2012 National Survey of Children’s Health. ASPE Research Brief. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2014. (http://198.246.124.29/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr074.pdf.)

Sousa L, Sorensen EJ. The Economic Reality of Nonresident Mothers and Their Children. New Federalism: National survey of America’s Families. Vol. B-69. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, 2006:1–7.

Ehrle J, Geen R, Clark RL Children Cared for by Relatives: Who Are They and How Are They Faring? New Federalism: National survey of America’s Families. Vol. B-28. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, 2001:1–7.

Ehrle J, Green R. Children Cared for by Relatives: What Services Do They Need? New Federalism: National Survey of America’s Families. Vol. B-28. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, 2002:1–7.

Szilagyi M. Kinship care. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:543–4.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. The AFCARS Report. Preliminary FY 2012 estimates as of November 2013. Washington. D.C. 2013; 20: 1–6. (https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport20.pdf.)

Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Harrington D, Starr R, Zuravin S, Sawyer R. Children in kinship care: How do they fare? Child Youth Serv Rev 1994;16:85–106.

Billing A, Ehrle J, Kortenkamp K. Children Cared for by Relatives: What Do We Know About Their Well-Being? New Federalism: National Survey of America’s Families. Vol. B-46. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, 2002:1–7.

Carpenter SC, Clyman RB, Davidson AJ, Steiner JF. The association of foster care or kinship care with adolescent sexual behavior and first pregnancy. Pediatrics 2001;108:E46.

Carpenter SC, Clyman RB. The long-term emotional and physical wellbeing of women who have lived in kinship care. Child Youth Serv Rev 2004;26:673–86.

Beeman SK, Kim H, Bullerdick SK. Factors affecting placement of children in kinship and nonkinship foster care. Child Youth Serv Rev 2000;22:37–54.

Rubin DM, Downes KJ, O’Reilly AL, Mekonnen R, Luan X, Localio R. Impact of kinship care on behavioral well-being for children in out-of-home care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:550–6.

Taussig HN, Clyman RB. The relationship between time spent living with kin and adolescent functioning in youth with a history of out-of-home placement. Child Abuse Negl 2011;35:78–86.

Stein RE, Hurlburt MS, Heneghan AM, et al. Health status and type of out-of-home placement: informal kinship care in an investigated sample. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:559–64.

Cauthen NK, Fass S. Measuring Poverty in the United States. National Center for Children in Poverty Fact Sheet. New York: Columbia University, 2008:1–4.

Baker LA, Mutchler JE. Poverty and material hardship in grandparent-headed households. J Marriage Fam 2010;72:947–62.

Yoshikawa H, Aber JL, Beardslee WR. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. Am Psychol 2012;67:272–84.

Aber JL, Bennett NG, Conley DC, Li J. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annu Rev Public Health 1997;18:463–83.

Pollitt RA, Rose KM, Kaufman JS. Evaluating the evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2005;5:7.

Evans GW, Cassells RC. Childhood poverty, cumulative risk exposure, and mental health in emerging adults. Clin Psychol Sci 2014; 2:287–296.

Agahi N, Shaw BA, Fors S. Social and economic conditions in childhood and the progression of functional health problems from midlife into old age. J Epidemiol Commun H 2014; 0:1–7.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Turner RB, et al. Childhood socioeconomic status, telomere length, and susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. Brain Behav Immun 2013;34:31–8.

Blair C, Raver CC. Child development in the context of adversity: experiential canalization of brain and behavior. Am Psychol 2012;67:309–18.

Lee CT, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH, Prybol K, Fuemmeler BF. Childhood economic strains in predicting substance use in emerging adulthood: mediation effects of youth self-control and parenting practices. J Pediatr Psychol 2013;38:1130–43.

Kim P, Evans GW, Angstadt M, et al. Effects of childhood poverty and chronic stress on emotion regulatory brain function in adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:18442–7.

Blair C, Berry D, Mills-Koonce R, Granger D ; FLP Investigators. Cumulative effects of early poverty on cortisol in young children: moderation by autonomic nervous system activity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013;38:2666–75.

Rutter M. Poverty and child mental health: natural experiments and social causation. JAMA 2003;290:2063–4.

Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135:e296–304.

Rutter M. How the environment affects mental health. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:4–6.

Hynes K, Dunifon R. Children in no-parent households: the continuity of arrangements and the composition of households. Child Youth Serv Rev 2007;29:912–932.

Bavier R. Children residing with no parent present. Child Youth Serv Rev 2011;33:1891–1901.

Mekonnen R, Noonan K, Rubin D. Achieving better health care outcomes for children in foster care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2009;56:405–15.

Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. American Academy of Pediatrics. The pediatrician’s role in helping children and families deal with separation and divorce. Pediatrics 1994; 94:119–121.

Casanueva C, Dozier M, Tueller S, et al. Caregiver instability and early life changes among infants reported to the child welfare system. Child Abuse Negl 2014;38:498–509.

Connell CM, Vanderploeg JJ, Flaspohler P, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Changes in placement among children in foster care: a longitudinal study of child and case influences. Soc Serv Rev 2006;80:398–418.

Rubin DM, Alessandrini EA, Feudtner C, Localio AR, Hadley T. Placement changes and emergency department visits in the first year of foster care. Pediatrics 2004;114:e354–60.

Webster D, Barth RP, Needell B. Placement stability for children in out-of-home care: a longitudinal analysis. Child Welfare 2000;79:614–32.

Wulczyn F, Kogan J, Harden BJ. Placement stability and movement trajectories. Soc Serv Rev 2003;77:212–236.

Font SA. Is higher placement stability in kinship foster care by virtue or design? Child Abuse Negl 2015;42:99–111.

Fisher PA, Van Ryzin MJ, Gunnar MR. Mitigating HPA axis dysregulation associated with placement changes in foster care. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011;36:531–9.

Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: distangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:1363–74.

Rubin DM, O’Reilly AL, Luan X, Localio AR. The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics 2007;119:336–44.

Manly JT, Cicchetti D, Barnett D. The impact of subtype, frequency, |chronicity, and severity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Dev Psychopathol 1994;6:121–43.

Hansen RL, Mawjee FL, Barton K, Metcalf MB, Joye NR. Comparing the health status of low-income children in and out of foster care. Child Welfare 2004;83:367–80.

Halfon N, Olson LM. Results from a new national survey of children’s health. Pediatrics 2004;113:1895–8.

Takayama JI, Wolfe E, Coulter KP. Relationship between reason for placement and medical findings among children in foster care. Pediatrics 1998;101:201–7.

Stahmer AC, Leslie LK, Hurlburt M, et al. Developmental and behavioral needs and service use for young children in child welfare. Pediatrics 2005;116:891–900.

Leslie LK, Gordon JN, Lambros K, Premji K, Peoples J, Gist K. Addressing the developmental and mental health needs of young children in foster care. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2005;26:140–51.

Clausen JM, Landsverk J, Ganger W, Chadwick D, Litrownik A. Mental health problems of children in foster care. J Child Fam Stud 1998;7:283–96.

Silver J, DiLorenzo P, Zukoski M, Ross PE, Amster BJ, Schlegel D. Starting young: improving the health and developmental outcomes of infants and toddlers in the child welfare system. Child Welfare 1999;78:148–65.

Dowd K, Kinsey S, Wheeless S, Thissen R, Richardson J, Suresh R. National survey of child and adolescent well-being (NSCAW) Combined Waves:1–4. 2004.

Runyan DK, Curtis PA, Hunter WM, et al. LONGSCAN: a consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. Aggress Violent Behav 1998;3:275–85.

U.S. Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration. National Survey of Children’s Health 2011–2012. (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm.)

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58.

Clarkson Freeman PA. Prevalence and relationship between adverse childhood experiences and child behavior among young children. Infant Ment Health J 2014;35:544–54.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Persistent Fear and Anxiety Can Affect Young Children’s Learning and Development. Working Paper No. 9. 2010. (http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu.)

Stevens JE. Spokane, WA, students’ trauma prompts search for solutions. 2012. (http://acestoohigh.com/2012/02/28/spokane-wa-students-child-trauma-prompts-search-for-prevention/.)

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury Prevention and Control: Division of Violence Prevention. 2015. (http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/.)

Berger LM, Bruch SK, Johnson EI, James S, Rubin D. Estimating the “impact” of out-of-home placement on child well-being: approaching the problem of selection bias. Child Dev 2009;80:1856–76.

Ahrens KR, Garrison MM, Courtney ME. Health outcomes in young adults from foster care and economically diverse backgrounds. Pediatrics 2014;134:1067–74.

Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2015.

The American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Foster Care. Fostering Health: Health Care for Children and Adolescents in Foster Care. 2nd edn. New York: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005:186.

Greiner MV, Ross J, Brown CM, Beal SJ, Sherman SN. Foster caregivers’ perspectives on the medical challenges of children placed in their care: implications for pediatricians caring for children in foster care. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2015;54:853–61.

Hillen T, Gafson L. Why good placements matter: pre-placement and placement risk factors associated with mental health disorders in pre-school children in foster care. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015;20:486–99.

Anderson J. The impact of family structure on the health of children: effects of divorce. Linacre Q 2014;81:378–87.

Nunes-Costa RA, Lamela DJ, Figueiredo BF. Psychosocial adjustment and physical health in children of divorce. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2009;85:385–96.

Fabricius WV, Luecken LJ. Postdivorce living arrangements, parent conflict, and long-term physical health correlates for children of divorce. J Fam Psychol 2007;21:195–205.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beal, S., Greiner, M. Children in nonparental care: health and social risks. Pediatr Res 79, 184–190 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.198

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.198

This article is cited by

-

Childcare Arrangements and Wellbeing of Children of Employed Women in Central Uganda

Child Indicators Research (2022)

-

Healthcare beliefs and practices of kin caregivers in South Africa: implications for child survival

BMC Health Services Research (2021)