Abstract

Refraction at a dielectric interface can take an anomalous character in anisotropic crystals, when light is negatively refracted with incident and refracted beams emerging on the same side of the interface normal. In soft matter subject to reorientation, such as nematic liquid crystals, the nonlinear interaction with light allows tuning of the optical properties. We demonstrate that in such material a beam of light can experience either positive or negative refraction depending on input power, as it can alter the spatial distribution of the optic axis and, in turn, the direction of the energy flow when traveling across an interface. Moreover, the nonlinear optical response yields beam self-focusing and spatial localization into a self-confined solitary wave through the formation of a graded-index waveguide, linking the refractive transition to power-driven readdressing of copolarized guided-wave signals, with a number of output ports not limited by diffraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light refraction at dielectric interfaces under the Snell–Descartes law is among the best known concepts in optics, its theoretical basis stemming from Maxwell’s equations and momentum conservation1. Ray-tracing techniques and the design of several optical devices rely on refraction. In isotropic media and at frequencies well removed from absorption regions, incident and refracted rays at an interface always lie on opposite sides of the normal to it, that is, they undergo standard (positive) refraction or, simply, refraction. Some natural and man-made media can also exhibit negative refraction, when both impinging and refracted rays belong to the same half-plane2. Owing to the conservation of momentum across the interface, negative refraction requires a nonzero walk-off angle between the phase velocity vp and the group velocity vg in the medium hosting the refracted beam. Two main types of light–matter interactions can satisfy this requirement: with backward waves when vp·vg≪0, or with forward waves when vp·vg>0, respectively2. The case of backward waves corresponds to the so-called negative refractive index, a counterintuitive phenomenon occurring in absorptive media or in metamaterials3,4. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Schuster (following W. Lamb’s original idea in mechanical systems) studied negative refraction considering backward waves in the presence of a lossy medium at an interface, and predicted its unobservability due to the evanescent character of the involved waves5. Nearly one century later, negative refraction was revived by Pendry’s seminal paper on the superlens effect based on amplified evanescent waves in a metamaterial6. Negative refraction in metamaterials has been recently demonstrated at microwave7,8 as well as near-infrared9, visible10 and ultraviolet wavelengths11. Surfing this wake of interest, researchers have also investigated negative refraction with forward waves, devoting special attention to photonic crystals12,13 and natural anisotropic media14,15. In the latter class of materials, where double refraction was first described by E. Bartholinus in the seventeenth century16, negative refraction stems from birefringent walk-off when the Poynting vector (directed as the energy flux) lies on the opposite side of the refracted wavevector with respect to the normal at the interface2.

The superlens effect in natural non-absorbing crystals is ruled out by the cutoff on transverse wavevectors (it might survive in photonic crystals when photons have a negative effective mass12 and behave as in a hyperbolic material17); nonetheless, negative (or backward) refraction remains relevant as it can maximize the angular beam deflection associated with impedance matching at an interface14. In this scenario, anisotropic soft matter—such as liquid crystals—has been used in the pursuit of electrically-adjustable negative refraction with either diffracting18,19 or self-confined beams20.

In this article, we report on nonlinear refraction with forward wavepackets in uniaxial nematic liquid crystals (NLCs): we obtained standard and negative light refraction at an interface using a single extraordinary polarization and were able to nonlinearly control the transition from one (positive) to the other (negative) by exploiting the walk-off dependence on beam power. At variance with previous attempts based on wave mixing15,21, in NLCs the optic axis can undergo reorientation by light self-action with continuous-waves at mW powers, achieving self-tunability of the beam direction, that is, self-steering: as the incident power increases, nonlinear walk-off modifies the light path and steers the refracted beam to the opposite side of the interface normal, achieving negative refraction with overall angular deflections as large as 7°. Moreover, reorientation is accompanied by self-focusing with beam self-localization into spatial solitary waves22: these are self-induced waveguides that permit to balance out the diffractive spreading, enhance the all-optical response, guide copolarized signals of different wavelengths and maximize the transverse resolution on steering, that is, the number of resolvable output spots or signal exit ports.

Results

Self-steering and negative refraction in NLCs

NLCs are states of matter sharing the properties of both solid-state crystals and liquids: they exhibit orientational order with the constituent elongated molecules randomly distributed in position23. The molecular orientation is macroscopically described by a space/time-dependent vector field, the molecular director  , collinear with the average alignment of the main (long) molecular axes. At optical frequencies, most NLCs are positive uniaxials with their optic axis along

, collinear with the average alignment of the main (long) molecular axes. At optical frequencies, most NLCs are positive uniaxials with their optic axis along  , extraordinary refractive index

, extraordinary refractive index  for electric fields oscillating parallel to

for electric fields oscillating parallel to  and ordinary index

and ordinary index  for fields normal to

for fields normal to  , respectively. NLCs exhibit a giant all-optical response observable with low-power continuous-wave excitations24, the reorientational optical nonlinearity: a suitably (extraordinarily) polarized electric field can induce molecular dipoles and make them reorient within the principal plane in order to minimize the system energy in the presence of elastic (intermolecular) interactions23,24. Such reorientational response is at the basis of a number of observed phenomena, ranging from bistability25 to pattern formation26, generation of complex topological structures27,28,29 or light-controlling-light; in particular, the latter has been exploited—at mW and sub-mW power levels—for generating, controlling and routing ‘nematicons’, that is, spatially self-localized beams stemming from the balance between transverse spatial dispersion (diffraction) and self-focusing22.

, respectively. NLCs exhibit a giant all-optical response observable with low-power continuous-wave excitations24, the reorientational optical nonlinearity: a suitably (extraordinarily) polarized electric field can induce molecular dipoles and make them reorient within the principal plane in order to minimize the system energy in the presence of elastic (intermolecular) interactions23,24. Such reorientational response is at the basis of a number of observed phenomena, ranging from bistability25 to pattern formation26, generation of complex topological structures27,28,29 or light-controlling-light; in particular, the latter has been exploited—at mW and sub-mW power levels—for generating, controlling and routing ‘nematicons’, that is, spatially self-localized beams stemming from the balance between transverse spatial dispersion (diffraction) and self-focusing22.

NLCs are ideal candidates for the observation of nonlinear negative refraction: they are highly birefringent (typically  in the visible spectrum), with walk-off (angular departure of Poynting vector from wavevector) as large as ≈7°, thus enhancing the role of anisotropy at dielectric interfaces30,31; moreover, they are transparent from infrared to ultraviolet, with losses mainly due to Rayleigh scattering23,24; finally, their response is such that a non-perturbative nonlinear regime can be experimentally accessed in the context of classical optics32.

in the visible spectrum), with walk-off (angular departure of Poynting vector from wavevector) as large as ≈7°, thus enhancing the role of anisotropy at dielectric interfaces30,31; moreover, they are transparent from infrared to ultraviolet, with losses mainly due to Rayleigh scattering23,24; finally, their response is such that a non-perturbative nonlinear regime can be experimentally accessed in the context of classical optics32.

The basic configuration for studying nonlinear tunable refraction from standard to negative in NLCs is sketched in Fig. 1. A thick NLC layer is homogeneously aligned in a planar cell with director  along the axis z normal to the input interface in z=0. A light beam is launched across the air-(glass)-NLC interface with input wavevector kin at an angle βin with respect to z; its electric field E oscillates in the principal plane yz of the uniaxial NLC and excites extraordinary waves. The system has mirror symmetry with respect to z, thus the light evolution is unaffected by the transformation βin → −βin. Fig. 1 illustrates the case βin≪0: the Snell–Descartes law provides the implicit equation β=arcsin [sinβin/ne(−β)] for the refraction angle β, where

along the axis z normal to the input interface in z=0. A light beam is launched across the air-(glass)-NLC interface with input wavevector kin at an angle βin with respect to z; its electric field E oscillates in the principal plane yz of the uniaxial NLC and excites extraordinary waves. The system has mirror symmetry with respect to z, thus the light evolution is unaffected by the transformation βin → −βin. Fig. 1 illustrates the case βin≪0: the Snell–Descartes law provides the implicit equation β=arcsin [sinβin/ne(−β)] for the refraction angle β, where  depends on the angle θ between

depends on the angle θ between  and k; in the linear regime θ corresponds to −β.

and k; in the linear regime θ corresponds to −β.

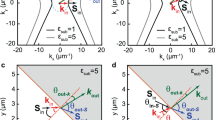

An extraordinarily polarized light beam impinges on the air-(glass)-NLC interface defining the input to the planar cell. (a) At low powers, the molecular director is parallel to z and positive refraction occurs for any incidence angle βin of wavevector kin. (b) As the input beam power increases, the reorientational torque rotates the director  towards the E-field vector (as indicated by the curved arrow in a), reducing the angle of refraction |β| and increasing the walk-off δ, eventually resulting in negative refraction when |βin| gets small enough. All angles are defined positive when taken clockwise with respect to the x axis: β remains negative regardless of the type of refraction, whereas γ changes sign in the transition from positive (Poynting vector S in the y≪0 half-plane) to negative (S in the y>0 half-plane) refraction. Insets: definitions of (lower inset) angle θ between k and

towards the E-field vector (as indicated by the curved arrow in a), reducing the angle of refraction |β| and increasing the walk-off δ, eventually resulting in negative refraction when |βin| gets small enough. All angles are defined positive when taken clockwise with respect to the x axis: β remains negative regardless of the type of refraction, whereas γ changes sign in the transition from positive (Poynting vector S in the y≪0 half-plane) to negative (S in the y>0 half-plane) refraction. Insets: definitions of (lower inset) angle θ between k and  (positive in the example) and (upper inset) angle ξ between

(positive in the example) and (upper inset) angle ξ between  and z. (c) Contour plot of wavevector angle β and (d) contour plot of Poynting vector angle γ versus director orientation ξ and incidence angle βin; the black solid line in (d) corresponds to a Poynting vector along z (that is, γ=0). (e) Graph of the largest βin versus ξ (black lines) corresponding to γ=0 (that is, maximum angle of incidence to support negative refraction, black line in d) and γ versus ξ for βin=−15° (red lines), respectively; solid and dashed lines are exact and approximate solutions, respectively. Here

and z. (c) Contour plot of wavevector angle β and (d) contour plot of Poynting vector angle γ versus director orientation ξ and incidence angle βin; the black solid line in (d) corresponds to a Poynting vector along z (that is, γ=0). (e) Graph of the largest βin versus ξ (black lines) corresponding to γ=0 (that is, maximum angle of incidence to support negative refraction, black line in d) and γ versus ξ for βin=−15° (red lines), respectively; solid and dashed lines are exact and approximate solutions, respectively. Here  =1.7 and

=1.7 and  =1.5; the wavelength of light is λ=1.064 μm.

=1.5; the wavelength of light is λ=1.064 μm.

Common NLCs are positive uniaxials with Δn>0; hence, the Poynting vector is always coplanar with the wavevector k and the optic axis  , and lies between them. The walk-off angle is

, and lies between them. The walk-off angle is  , with

, with  the optical anisotropy; therefore, δ and θ have the same sign. Defining γ the angle of the Poynting vector with z, in the linear regime it is γβ>0, that is, light rays undergo positive refraction for every incidence angle βin. In the nonlinear regime, conversely, the reorientation of the optic axis can affect the beam (ray) direction. With reference to Fig. 1, an extraordinarily polarized light beam can induce a rotation of the molecular director

the optical anisotropy; therefore, δ and θ have the same sign. Defining γ the angle of the Poynting vector with z, in the linear regime it is γβ>0, that is, light rays undergo positive refraction for every incidence angle βin. In the nonlinear regime, conversely, the reorientation of the optic axis can affect the beam (ray) direction. With reference to Fig. 1, an extraordinarily polarized light beam can induce a rotation of the molecular director  away from the wavevector, in turn increasing the size of the walk-off |δ|. Even if β remains negative for every angle ξ between

away from the wavevector, in turn increasing the size of the walk-off |δ|. Even if β remains negative for every angle ξ between  and z, since θ=ξ−β the Poynting vector can change side with respect to z, giving rise to negative refraction when |δ|>|β|.

and z, since θ=ξ−β the Poynting vector can change side with respect to z, giving rise to negative refraction when |δ|>|β|.

From Fig. 1 and the Snell–Descartes law, it is straightforward to obtain the refraction angle for light rays as

In the limit of small incidence angles βin, equation (1) gives

where we set  . Neglecting the terms containing powers of εa larger than 2, it stems from equation (2) that negative refraction can only occur if

. Neglecting the terms containing powers of εa larger than 2, it stems from equation (2) that negative refraction can only occur if

Figure 1c,d graph wavevector and Poynting vector angular directions in the NLC versus the two free parameters, that is, director orientation ξ and angle of incidence βin (in the interval [−15° 0°]); we set  =1.7 and

=1.7 and  =1.5 as in the E7 mixture at 1064, nm (ref. 33). When |βin|≪5°, the refraction angle β slightly changes with ξ, never exceeding variations of 1°; negative refraction occurs for small βin, with smaller βin corresponding to larger negative refraction. Figure 1e compares approximate (from equation (2)) and exact solutions (from equation (1)) for γ in the (worst) case βin=−15°; in the same figure (red lines) the validity of equation (3) is apparent in calculating the maximum input beam tilt, which permits the observation of negative refraction. Exact and approximate results are mutually consistent to a good accuracy.

=1.5 as in the E7 mixture at 1064, nm (ref. 33). When |βin|≪5°, the refraction angle β slightly changes with ξ, never exceeding variations of 1°; negative refraction occurs for small βin, with smaller βin corresponding to larger negative refraction. Figure 1e compares approximate (from equation (2)) and exact solutions (from equation (1)) for γ in the (worst) case βin=−15°; in the same figure (red lines) the validity of equation (3) is apparent in calculating the maximum input beam tilt, which permits the observation of negative refraction. Exact and approximate results are mutually consistent to a good accuracy.

Experimental verification

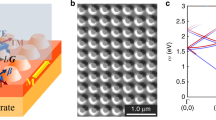

To validate our prediction with experiments, we prepared a planar glass cell of thickness L=100 μm across x, filled it with the E7 mixture (Δn≈0.2) and sealed the input to ensure a homogeneous director distribution and the absence of a meniscus22. The molecular director was aligned along the normal z to the input interface, as in Fig. 1a. Due to the cell shape, the sample was subject to one-dimensional boundary effects versus x but could be considered infinitely extended across y (ref. 34). A TEM00 laser beam of wavelength λ=1.064 μm was gently focused into the sample, slightly past the input glass/NLC interface to avoid spurious interactions with the molecules anchored at the boundary; the input waist was set to w0≈8 μm by using two lenses in a telescopic arrangement and a microscope objective. Two mirrors (M1 and M2 in Fig. 2) ensured accurate control of the input conditions, particularly the incidence angle βin.

(a) Sketch of the experimental set-up: lenses L1 and L2 form a telescope; mirror M1 is fixed, mirror M2 can be translated to adjust the beam path and the incidence angle. (b) Beam trajectories in the linear limit (2 mW input power) for βin=0° (red line with triangle), ±1.5° (green line with square and cyan line with star) and ±5° (blue line with circle and magenta line with diamond); solid and dashed lines correspond to extraordinary and ordinary waves, respectively. (c) Normalized beam width w/w0 versus z at normal incidence for βin=0° and 2 mW input power. Here w0=8 μm.

The beam-to-cell alignment was monitored by acquiring the trajectories of extraordinary and ordinary rays propagating in the linear regime (Fig. 2b), using a CCD (charge-coupled device) camera to collect the out-of-plane (yz) scattered light; the acquired beam paths could then be compared with the calculated ones (Fig. 1c,d; ref. 35). A second CCD camera was used to acquire the output profile through the exit facet of the sample. Fig. 2c shows the measured beam width, defined as  , versus z in the linear regime and normalized with respect to w0; A is the amplitude of the light wavepacket. In the described conditions (cell configuration, beam waist, small βin and low power), beam propagation was ruled by diffraction, with a Rayleigh distance of ≈280 μm.

, versus z in the linear regime and normalized with respect to w0; A is the amplitude of the light wavepacket. In the described conditions (cell configuration, beam waist, small βin and low power), beam propagation was ruled by diffraction, with a Rayleigh distance of ≈280 μm.

When the optical excitation is larger (in the highly nonlinear regime), nonlinear refraction can take place: the director orientation ξ depends on the input power through optical reorientation, providing in turn a change in walk-off36; in addition, a (smaller) nonlinear correction of β is caused by the increase of the extraordinary refractive index ne(β) (see Eq.(1) and Fig. 1c). Therefore, for high-enough excitations the light beam can adjust the direction of its own Poynting vector by altering the walk-off.

Figure 3a displays the acquired images of beam evolution and output profile for βin=−4.9°. As expected, the beam moves sideways versus input power. At variance with the predictions of equation (2), however, it does not propagate straight when steered by way of nonlinear walk-off: the observed bending is due to scattering losses, which cause a reduction in beam power versus z, hence a reduced nonlinear response with progressively vanishing reorientation36. In particular, for P≈30 mW the beam positions at sample input and output nearly coincide, with an apparent γ=0 resulting at the exit. Further increases in input power allow for negative refraction, that is, the outgoing beam can be seen to emerge in the same half-plane y>0 of the incident beam (rightmost panels of Fig. 3a for P>30 mW).

(a) Beam evolution in the observation plane yz (left) and output profiles in the transverse plane xy (right) when βin=−4.9°. The dashed line indicates the cell mid-section y=0. (b) Corresponding trajectories and (c) normalized beam width versus z for an input power of 2 mW (blue line with circle), 20 mW (green line with square), 30 mW (red line with star), 40 mW (cyan line with cross), 70 mW (magenta line with plus) and 100 mW (yellow line with inverted triangle). The black dashed line in b indicates the trajectory in the linear regime when |βin|≈0° within the experimental accuracy. Inset in b: angle γ versus input power, measured in z=150 μm (black line with circle), z=500 μm (clay line with square) and z=1 mm (mustard line with triangle). Inset in c: normalized beam width versus power measured in z=250 μm.

For a better assessment of the phenomenon, Fig. 3b,c plot the beam trajectories and normalized widths versus z, corresponding to Fig. 3a. The paths change non-monotonically with power due to the δ dependence on θ, with a maximum δ for θ≈45° (Fig. 1d). The combined effect of (scattering) losses and nonlinear walk-off is responsible for the change (in both amplitude and sign) of the initial slope of the trajectories. As stated above, a stronger reorientation corresponds to a larger walk-off up to its maximum, with the opposite trend for further (nonlinear) increases in θ: the analysis of the trajectories (Fig. 3b) and their slope (inset Fig. 3b) allows estimating an angle θ≈45° near the input interface for powers slightly above P=40 mW. For P=30 mW the angle γ results positive up to z≈600 μm, then retrieves its linear value owing to vanishing reorientation, as losses reduce the local beam power. For P≈40 mW the maximum orientation is≈45°: γ monotonically decreases along z, going from positive to negative values after a propagation distance z which lengthens with power. For P>70 mW the initial γ reduces as power increases, conserving its sign along z. Eventually, for P≈100 mW, the Poynting vector angle γ monotonically increases versus z up to a maximum, with θ≈45° at the output.

Furthermore, the measured beam width confirms the occurrence of light self-trapping, more and more effective as power increases (Fig. 3c). For P=30 mW and P=40 mW, when the beam profile gets narrower (that is, self-confinement is stronger, inset in Fig. 3c), the outgoing beam results wider due to the stronger diffraction after losses prevail on self-focusing. In particular, the minimum waist is obtained for P=40 mW, confirming the value of θ≈45° inferred from Fig. 3b when the nonlinearity is maximized. For P=100 mW, in the early stages of propagation the beam is wider than at lower powers due to saturation of the nonlinear response (θ>45° (ref. 32)).

The power-controlled steering action is shown in Fig. 4, for the case βin=−4.9°. Clearly, in the solitary regime the beam size is of the order of the input width (see inset), permitting to resolve a large number of output positions versus y, that is, a number of output ports for signals guided by solitons. Careful engineering (reducing input waist and scattering losses, increasing wavelength and propagation distance) could easily result in spatial readdressing to >30 output channels with negligible crosstalk.

Output beam position on the y axis versus input power, for an angle of incidence βin=−4.9°. The self-confined beam and the associated graded-index waveguide undergo angular steering and transverse displacement versus excitation. The resulting power-controlled router has a number of output ports (and outgoing guided-wave signals) defined by the overall angular span and the width of the self-trapped beam. The inset shows a typical self-guided (solitary) beam profile (P=30 mW).

The experimental results on nonlinear beam refraction are summarized in Fig. 5: the output beam position in y changes with input power for various incidence angles βin. Nonlinear negative refraction is largest for small βin, consistently with Fig. 1d. The maximum nonlinear deflection of the beam was obtained for a finite βin, rather than the predicted βin=0, because powers above an upper value caused the beam to wiggle strongly due to temporal instabilities in the medium37,38. Figure 5a is not perfectly symmetric due to the unavoidable sample imperfections and the finite experimental accuracy. For an input power of 100 mW, the graph shows a maximum nonlinear deflection of about 150 μm, the largest self-steering obtained to date (significantly larger than in ref. 36) via power-dependent walk-off. Finally, we checked the mirror symmetry of our sample by comparing the experimental data for positive and negative βin: the plots in Fig. 5b,c confirm that, within measurement errors, the system is specularly symmetric.

(a) Output beam position in y versus βin, measured in z=1.1 mm for an input power of 2 mW (blue with circle), 20 mW (green with square), 30 mW (red with triangle), 40 mW (cyan with dot), 70 mW (magenta with star) and 100 mW (yellow with diamond). (b) Beam paths for βin≪0 and (c) beam paths for βin>0: input powers are 2 mW (linear case, dashed lines) and 70 mW (solitary wave propagation, solid lines). The incidence angles for βin≪0 (βin>0) are −9.2° (7.6°) (blue with circle), −4.9° (4.3°) (green with square), −1.6° (1.0°) (red with triangle). The dashed black lines with dot are the paths corresponding to βin≈0°.

Discussion

We reported on the first experimental observation of nonlinear refraction—from positive to negative — by beam self-action in reorientational NLCs, supported by walk-off dependence on beam power when the nonlinear response becomes comparable with the linear one. While both light self-deflection and nonlinear negative refraction could be observed in other anisotropic media with a reorientational nonlinearity39, our geometry in NLCs optimizes their observation and characterization in highly nonlinear and highly anisotropic soft matter. This work may impact in the study of light-matter interactions towards the design and realization of novel light-controlling-light devices and systems. Here nonlinear refraction is obtained through self-confinement and solitary wave propagation at relatively low powers; hence, self-trapped optical wavepackets in space enhance the nonlinear response and make this configuration appealing towards power-steerable waveguides or reconfigurable interconnects, where the same optical element realizes both signal guidance and control. Accessing the negative refraction regime enables to maximize the total angular span of such waveguide steering, permitting to resolve a large number of output ports (channels) and increase the system capacity. As further developments, we envisage the generalization of the phenomena here shown to, for example, optomechanical meta-atoms39,40, soft matter with metallic nanoparticles41, solutions of graphene-oxide flakes42. We also foresee fascinating new phenomena stemming from the combined effects of artificial magnetoelectric coupling in metamaterials and natural dielectric anisotropy, for example, exploring the tunability of liquid crystals-based metamaterials43, where the interplay of nonlinear refraction (discussed hereby) and a negative refractive index or negative diffraction could be exploited towards novel exotic phenomena.

Methods

Modeling light propagation in the nonlinear regime

In the nonlinear regime, in the absence of losses and under the single elastic constant (K) approximation24, an extraordinarily polarized electromagnetic wave in the harmonic regime at pulsation ω propagates in reorientational uniaxial NLC according to

where εij are Cartesian components of the dielectric tensor, μ0 is the magnetic permeability of vacuum, H and E are the magnetic (linearly polarized along x) and electric (polarized in yz) fields, respectively; the subscript t in equation (6) refers to the local polarization of the electric field, in turn determined by γ. Owing to the highly nonlocal response of NLC22,24, all the dielectric parameters in equations (4, 5, 6) can be evaluated on the beam axis, except for  , which is responsible of self-focusing32. Thus, the walk-off angle is δ(ξmax−β), with ξmax(z) the maximum reorientation at the field peak on each z.

, which is responsible of self-focusing32. Thus, the walk-off angle is δ(ξmax−β), with ξmax(z) the maximum reorientation at the field peak on each z.

Sample preparation

The planar cells used in the experiments consist of two parallel glass slides placed normal to the x axis, measuring 1.5 and 40 mm along z and y, respectively: the length along z allows observing the output profiles despite scattering losses; the width along y allows preventing boundary effects. The cell thickness across x, Lx=100 μm determined by Mylar spacers, ensures both bulk-like beam propagation and operation in the highly nonlocal regime32. Both slides were covered by a polymer (polyvinyl carbazole doped with C60) thin film and mechanically rubbed along z in order to ensure the planar alignment of the molecular director along the z axis, with a pretilt angle ≈0°, as measured by the crystal rotation method44. The cell was uniformly filled with the commercial nematic mixture E7 by capillarity. To maximize the coupling of the input laser beam to the extraordinary wave component in the NLC layer, two additional glasses of thickness 100 μm were attached to the edges of the cell (perpendicular to z in z=0 and z=1.5 mm) using ultraviolet curable glue after depositing a thin polyimide layer; these two glasses were treated to induce homeotropic alignment, thus ensuring a homogeneous director distribution in absence of external stimuli. Such input and output glass facets prevented the formation of NLC menisca and undesired beam depolarization at the input, as well as degradation of the sample in time.

Experimental set-up

Accurate measurements of beam incidence were carried out by calibrating the angular deflection of the beam after the microscope objective (MO) against the lateral shift of the mirror (M2, Fig. 2a), mechanically controlled with a resolution of 1 μm. The sample was placed as close as possible to MO in order to minimize changes in the impact point, the latter changes being detrimental when trying to avoid artifacts associated with possible inhomogeneities in director distribution at the input facet. The input beam direction corresponding to the optimum parallelism between the input wavevector and the z axis (normal to the input facet) was achieved by maximizing the overlap of the trajectories of ordinary (input polarization along x) and extraordinary (input polarization along y) components in the sample at low powers (linear regime): ordinary- and extraordinary-wave Poynting vectors are collinear when the initial wavevector is parallel to the optic axis. The evolution (plane yz) and output profiles (plane xy) of the beams were imaged by single-shot acquisitions of the out-of-plane scattered light and intensity distribution at the exit facet, respectively. The measured trajectories and beam widths were averaged over several acquisitions to reduce the impact of noise.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Piccardi, A. et al. Power-controlled transition from standard to negative refraction in reorientational soft matter. Nat. Commun. 5:5533 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6533 (2014).

References

Born, M. & Wolf, E. Principles of Optics Pergamon Press (1975).

Boardman, A. D., King, N. & Velasco, L. Negative refraction in perspective. Electromagnetics 25, 365–389 (2005).

Veselago, V. G. The Electrodynamics of Substances with Simultaneously Negative Values of ε and μ. Sov. Phys. Usp. 10, 509 (1968).

Zheludev, N. I. The road ahead for metamaterials. Science 328, 582–583 (2010).

Schuster, A. An Introduction to the Theory of Optics Edward Arnold (1904).

Pendry, J. B. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3966–3969 (2000).

Smith, D. R., Padilla, W. J., Vier, D. C., Nemat-Nasser, S. C. & Schultz, S. Composite medium with simultaneously negative permeability and permittivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4184–4187 (2000).

Parazzoli, C. G., Greegor, R. B., Li, K., Koltenbah, B. E. C. & Tanielian, M. Experimental verification and simulation of negative index of refraction using Snell’s law. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 107401 (2003).

Shalaev, V. M. et al. Negative index of refraction in optical metamaterials. Opt. Lett. 30, 3356–3358 (2005).

Yao, J. et al. Optical negative refraction in bulk metamaterials of nanowires. Science 321, 930 (2008).

Xu, T., Agrawal, A., Abashin, M., Chau, K. J. & Lezec, H. J. All-angle negative refraction and active flat lensing of ultraviolet light. Nature 497, 470–474 (2013).

Luo, C., Johnson, S. G., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Pendry, J. B. All-angle negative refraction without negative effective index. Phys. Rev. B 65, 201104 (2002).

Cubukcu, E., Aydin, K., Ozbay, E., Foteinopoulou, S. & Soukoulis, C. Negative refraction by photonic crystals. Nature 423, 604–605 (2003).

Zhang, Y., Fluegel, B. & Mascarenhas, A. Total negative refraction in real crystals for ballistic electrons and light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 157404 (2003).

Harutyunyan, H., Beams, R. & Novotny, L. Controllable optical negative refraction and phase conjugation in graphene. Nat. Phys. 9, 423 (2013).

Bartholinus, E. Experimenta Crystalli Islandici Disdiaclastici Quibus Mira Et Insolita Refractio Detegitur Hafniae (1669).

Jacob, Z., Alekseyev, L. V. & Narimanov, E. Optical hyperlens: Far-field imaging beyond the diffraction limit. Opt. Express 14, 8247–8256 (2006).

Pishnyak, O. P. & Lavrentovich, O. D. Electrically controlled negative refraction in a nematic liquid crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 251103 (2006).

Kang, L., Zhao, Q., Li, B., Zhou, J. & Zhu, H. Experimental verification of a tunable optical negative refraction in nematic liquid crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 181391 (2007).

Peccianti, M. & Assanto, G. Nematicons across interfaces: anomalous refraction and reflection of solitons in liquid crystals. Opt. Express 15, 8021–8028 (2007).

Katko, A. R. et al. Phase conjugation and negative refraction using nonlinear active metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 123905 (2010).

Peccianti, M. & Assanto, G. Nematicons. Phys. Rep. 516, 147–208 (2012).

Simoni, F. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Liquid Crystals World Scientific (1997).

Khoo, I. C. Nonlinear optics of liquid crystalline materials. Phys. Rep. 471, 221–267 (2009).

Khoo, I. C. Optical bistability in nematic films utilizing selffocusing of light. Appl. Phys. Lett. 41, 909–911 (1982).

Residori, S. Patterns, fronts and structures in a liquid-crystal-light-valve with optical feedback. Phys. Rep. 416, 201–272 (2005).

Chen, B. G.-g., Ackerman, P. J., Alexander, G. P., Kamien, R. D. & Smalyukh, I. I. Generating the hopf fibration experimentally in nematic liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 237801 (2013).

Ketara, M. E. & Brasselet, E. Observation of self-induced optical vortex precession. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 233603 (2013).

Barboza, R. et al. Harnessing optical vortex lattices in nematic liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 093902 (2013).

Peccianti, M., Assanto, G., Dyadyusha, A. & Kaczmarek, M. Non-specular total internal reflection of spatial solitons at the interface between highly birefringent media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 113902 (2007).

Alberucci, A. et al. Interactions of accessible solitons with interfaces in anisotropic media: the case of uniaxial nematic liquid crystals. New J. Phys. 15, 043011 (2013).

Alberucci, A. & Assanto, G. Nematicons beyond the perturbative regime. Opt. Lett. 35, 2520–2522 (2010).

Li, J., Wu, S.-T., Brugioni, S., Meucci, R. & Faetti, S. Infrared refractive indices of liquid crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 073501–073505 (2005).

Alberucci, A., Peccianti, M. & Assanto, G. Nonlinear bouncing of nonlocal spatial solitons at the boundaries. Opt. Lett. 32, 2795–2797 (2007).

Kwasny, M. et al. Self-guided beams in low-birefringence nematic liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. A 86, 013824 (2012).

Piccardi, A., Alberucci, A. & Assanto, G. Soliton self-deflection via power-dependent walk-off. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 061105 (2010).

Beeckman, J., Neyts, K., Hutsebaut, X., Cambournac, C. & Haelterman, M. Time dependence of soliton formation in planar cells of nematic liquid crystals. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 41, 735–740 (2005).

Peccianti, M., Dyadyusha, A., Kaczmarek, M. & Assanto, G. Escaping solitons from a trapping potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 153902 (2008).

Zharov, A. A., Zharov, A. A. & Zharova, N. A. Spontaneous reorientations of meta-atoms and electromagnetic spatial solitons in a liquid metacrystal. Phys. Rev. E 90, 023207 (2014).

Liu, M. et al. Nonlinear response via intrinsic rotation in metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 87, 235126 (2013).

Dintinger, J. et al. A self-organized anisotropic liquid-crystal plasmonic metamaterial. Adv. Mater. 25, 1999–2004 (2013).

Shen, T.-Z., Song, S.-H. & Song, J.-K. Electro-optical switching of graphene oxide liquid crystals with an extremely large kerr coefficient. Nat. Mater. 13, 394–399 (2014).

Buchnev, O., Ou, J. Y., Kaczmarek, M., Zheludev, N. I. & Fedotov, V. A. Electro-optical control in a plasmonic metamaterial hybridised with a liquid-crystal cell. Opt. Express 21, 1633–1638 (2013).

Han, K., Miyashita, T. & Uchida, T. Accurate determination and measurement error of pretilt angle in liquid crystal cell. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 32, 277–279 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor M. Kaczmarek (University of Southampton, UK) for useful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All co-authors contributed equally to this work. A.P. and N.K. performed the experimental measurements and analysed the data, A.A. developed the concept, dealt with model and numerical simulations. O.B. realized the sample. G.A. gave conceptual advice and supervised the work. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piccardi, A., Alberucci, A., Kravets, N. et al. Power-controlled transition from standard to negative refraction in reorientational soft matter. Nat Commun 5, 5533 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6533

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6533

This article is cited by

-

Curved optical solitons subject to transverse acceleration in reorientational soft matter

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Magnetic routing of light-induced waveguides

Nature Communications (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.