Abstract

Magnetic inhomogeneity at a superconductor (S)–ferromagnet (F) interface converts spin-singlet Cooper pairs into spin-one triplet pairs. These pairs are immune to the pair-breaking exchange field in F and support a long-range proximity effect. Although recent experiments have confirmed the existence of spin-polarized triplet supercurrents in S–F–S Josephson junctions, reversible control of the supercurrent has been impossible because of the robust preconfigured nature of the inhomogeneity. Here, we use a barrier comprising three F layers whose relative magnetic orientation, and hence the interfacial inhomogeneity, can be controlled by small magnetic fields; we show that this enables full control of the triplet supercurrent and, by using finite element micromagnetic simulations, we can directly relate the experimental data to the theoretical models which provide a general framework to understand the role played by magnetic states in long-range supercurrent modulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interplay between superconducting and magnetic order parameters constrained by the exclusion principle and fermionic exchange statistics has given rise to rich and diverse physics and reignited the interest in the problem of coexistence of magnetism and superconductivity1,2. Of particular relevance is the theoretical prediction3 that magnetic inhomogeneity at a S–F interface leads to a conversion between singlet and triplet spin pairing states in different quantization bases and produces equal spin Cooper pairs. Recent experimental verification4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 of long-ranged supercurrents in ferromagnets has raised the intriguing possibility of taking the next step towards practical implementation as a dissipation-less version of spin electronics (spintronics)16. Two key aspects need to be addressed for a realization of such circuits: efficient generation of spin-polarized supercurrents, and their active control. Efforts17,18,19 in the last few years have been primarily directed towards optimizing the supercurrent; little progress has so far been made in directly controlling it. Optimizing the inhomogeneity in the form of a robust spin-mixer layer that maximizes the singlet to triplet conversion ironically appears to make it difficult to design an externally controllable system.

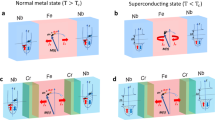

In this article, we report SF′FF′S Josephson junctions in which the magnetic alignment between thin F′ mixer layers (composed of the soft ferromagnet Ni80Fe20, Permalloy, Py) and a thicker F layer (Co) can be controlled by the applied magnetic field (H) and show that the magnitude of the critical current IC is controlled by the net misalignment of the magnetism in the three layers. In particular, we show that the supercurrent is zero for the parallel aligned case (Fig. 1a,b). This device is the superconducting analogue of the spin valve, which is the foundation of conventional spintronics20. We analyse our results based on the Houzet and Buzdin model21 of a Josephson junction incorporating a trilayer magnetic structure which, in combination with finite element analysis, provides a semi-quantitative fit to the data.

(a) At high magnetic fields, the F layers are parallel and the combined F layer thickness is much greater than the coherence length of the singlet Cooper pairs; no supercurrent flows through the structure. (b) At zero or low magnetic fields, the inhomogeneous or non-collinear F′ layers converts the spin-singlet Cooper pairs in S to equal spin-triplet Cooper pairs in F thus allowing a finite triplet supercurrent to flow through the structure.

Results

Transport measurements of SF′FF′S Josephson junctions

Figure 2a shows the IC in a Josephson junction with a Py(1.5)/Cu(5)/Co(5.5)/Cu(5)/Py(1.5) (thicknesses in nanometres) barrier. The behaviour is distinctly different from the expected dependence of IC on H (IC(H)) in a SFS Josephson junction: an example is shown in Fig. 2b from a junction incorporating Ho mixer layers at the S/F interface but having similar Co layer thickness (6 nm) and comparable dimensions in which, although hysteretic, IC(H) clearly follows the expected Fraunhofer-type dependence with distinct second lobes. In Fig. 2a and, Fig. 3a we observe that the overall shape and behaviour of IC(H) is very different: IC goes to zero above a certain field magnitude instead of showing multiple oscillations with field (confirmed by the linear current–voltage characteristic recorded at −40 mT (Fig. 3a inset)); the small rise seen at high fields is associated with thermal effects arising from the magnet coil. On reducing the central Co layer thickness to 3 nm, which enables a singlet contribution to the supercurrent, although the central peak remains strongly distorted, additional lobes reappear beyond the first minima (Fig. 2c).

(a) The junction is composed of a stack of Nb(250 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Py(1.5 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Co(5.5 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Py(1.5 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Nb(250 nm). (b) Josephson junction with 6 nm central Co layer but having 4.5-nm thick Ho layers at Nb/Co interface instead of Py to generate spin-polarized supercurrents. It shows a Fraunhofer-like dependence of the junction critical current with prominent side lobes. (c) A Josephson junction having a layer sequence similar to a but with a reduced central Co thickness of 3 nm showing oscillations of the critical current beyond the first lobe. The approximate dimensions of all the junctions are 600 × 500 nm. The red dotted lines in a–c represent the shift in the zero critical current line due to the finite non-zero voltage used to measure the critical current (see Methods for details).

(a) Critical current versus in-plane magnetic field of a Nb/Cu(5 nm)/Py(1.5 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Co(5.5 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Py(1.5 nm)/Cu(5 nm)/Nb junction measured at 4.2 K. The red dotted line in a representing the shift in the zero critical current line due to the finite non-zero voltage used to measure the critical current (see Methods for details). The inset shows the current–voltage characteristic of the junction recorded at −40 mT to verify the absence of critical current. (b) Simulated IC(H) pattern (green and brown curves) showing the combined effect of inhomogeneous magnetic state giving rise to a spin-polarized supercurrent and the effect of the flux taking into account the magnetic inhomogeneity. The green curve takes into account the actual sign of sin φ1 sin φ2 and thus accounts for the sign of the supercurrent depending on local 0 or π states, whereas the brown curve only takes the modulus of sin φ1 sin φ2. Inset shows the variation of the maximum supercurrent (IC0) in the junction and the combined effect of flux arising from an inhomogeneous barrier moment and the applied field on the critical current as a function of an in-plane applied magnetic field. (c, i–v) The plan views of the magnetic states (from OOMMF simulations) for outer Py and central Co layers are shown with the corresponding magnetic fields as indicated below. The states corresponding to the field values shown are also marked in b.

Although unusual IC(H) patterns have been reported before in SFS, SF′FF′S or SIFS Josephson junctions17,22,23,24, these are irreproducible and attributed to stochastic variations of the flux arising from a multi-domain magnetic barrier. This is distinctly different from what we observe here: a highly reproducible but strongly distorted central peak with zero critical current beyond a certain magnetic field value.

We start the discussion of these results by setting an upper limit for the singlet IC through such devices. In general, the singlet IC in SFS Josephson junctions will be oscillatory with multiple 0–π transitions with increasing F thickness25,26, but to provide an estimate of the upper limit of the singlet current we just consider the envelope of the IC maxima—in other words, assuming that the net exchange energy of the barrier is such that singlet pair dephasing is zero and that the supercurrent is just limited by the coherence lengths. The singlet coherence lengths ξCo and ξPy have been measured to be 3.0 and 1.4 nm, respectively27, meaning that the total F barrier thickness is equivalent to 12 nm of Co for the device shown in Figs 2a and 3a. Taking a typical value of 1.5 μV as the characteristic voltage (ICRN) in such junctions (extrapolated for 12 nm Co thickness) previously observed for Nb/Co/Nb26, gives a maximum singlet IC of ~ 40 μA. This value does not take into account the additional scattering at the multiple interfaces in our structures28. To take account of these interfaces and at least partial cancellation of the dephasing, a more representative number might be obtained by extrapolating from similar sized junctions with much thinner Py(1.6)/Cu(8)/Co(1) ferromagnetic barriers29, for which the ICRN varied between 0.8 and 2 μV thus, giving a maximum IC of ~60 μA when the two F layers were AP. In our devices, the ICRN ranged from 4 to 11 μV with a corresponding IC of ~500–600 μA. We therefore conclude that the supercurrents cannot originate from singlet pair transport and so must be primarily mediated by spin-one triplet pairs.

The non-collinearity between the adjacent F layers that is required for triplet generation21 arises from the complex magnetic microstructure of the F layers, which itself is due to a competition between the dipolar field30,31,32, magnetic anisotropies and the external field. Since this microstructure changes with the applied field, the maximum critical current, IC0 should depend on H.

For our junctions, the IC(H) modulation is controlled by two factors: first, the field-dependent magnetic inhomogeneity determines the maximum triplet supercurrent IC0 and, second, phase variations arising from the applied field and induced changes to the net barrier moment determine the net IC (which leads to the Fraunhofer IC(H) modulation seen in conventional junctions). Both of these factors depend on the details of the micromagnetic configuration of each magnetic layer and so it is necessary to understand how this depends on H.

Finite element analysis of IC dependence on magnetic field

Experimentally, it is hard to directly visualize these states in sub-micron devices and, although previous SFS experiments have used indirect information from magnetic measurements of unpatterned films, the much weaker role of dipolar fields in continuous films means that it is impossible to directly relate the details of the micromagnetic structure of nanopillar devices from such measurements. Instead, we have used finite element micromagnetic simulations33 using Object Oriented Micromagnetic Framework (OOMMF), which allows simulation of the magnetic state up to a resolution of few nanometres and make semi-quantitative predictions relating the magnetic structure to the spin-polarized supercurrent flowing through the device. The saturation magnetization, exchange coefficient and uniaxial anisotropy for Co were set to 1,400 × 103 Am−1, 3 × 10−11 Jm−1 and 208 × 103 Jm−3, respectively, while for Py these values were 860 × 103 Am−1, 1.3 × 10−11 Jm−1 and 150 Jm−3, respectively. The saturation magnetization and exchange coefficient values were taken from the OOMMF database (used in the literature); the saturation magnetization agrees closely with the values we have calculated from bulk films deposited on SiO2 substrates sandwiched between 100-nm thick Cu. The uniaxial anisotropy for Py was calculated from the difference in area of the hysteresis loops measured along the hard and easy axis and the direction, originally set by the growth field, was orthogonal to the applied field H. However, it is seen that the dipolar energy term in this case is much larger than the Py anisotropy energy and alone dictates the ground state configuration. To determine the value of Co anisotropy, we have simulated a spin valve structure consisting of Co (1.5)/Cu (7.5)/Py (1.5) similar to the one used in ref. 29, which was grown under similar conditions and modified the Co anisotropy value to match the switching field obtained from magnetoresistance measurements on these structures. The value obtained from these simulations is 40% of the reported value in OOMMF database; this is not unexpected since the anisotropy strongly depends on the growth conditions, the substrate used and the film thickness34. The Co anisotropy was in the plane of the layer and the direction was chosen from a random vector field, which reflects the polycrystalline nature of the sputtered films. The damping coefficient was set to 0.5, which allowed for rapid convergence.

Figure 3a shows one branch (positive to negative field sweep) of IC(H) for a device. Micromagnetic simulations for this device have been performed at 5-mT intervals for an equivalent field sweep: Fig. 3c shows plan views of the magnetic structure of each layer at representative fields. The colour scheme adopted to represent magnetization direction is red-white-blue with red (blue) pixels representing magnetization aligned along the positive (negative) external field direction. White pixels represent magnetic moments orthogonal to the applied field direction. At the highest field magnitudes, the three F layers are parallel. Around 10 mT, the Py layers start inhomogeneously reversing under the dipolar magnetostatic interaction from the Co layer and are fully reversed at zero field. As the field increases in the negative direction the Co layer eventually reverses beyond −10 mT. It is clear from the images that significant non-collinearity exists within and between all layers during the reversal process.

This observation is important in its own right as there have been speculations about the specific origin of spin-polarized supercurrents in SF′FF′S devices before. Although it was concluded by Khasawneh et al.23 that non-collinearity between F′ and F layers most likely gives rise to the spin-polarized supercurrents rather than inhomogeneity in F′ layers, our simulations indicate a more subtle effect at play. Intuitively one might be inclined to believe that there is little inhomogeneity in nano-pillar devices, but it is evident here that inhomogeneity does exist and if engineered properly using F layer with difference in coercivities, this can be translated to a local non-collinearity between Py and Co layers, which is critical for spin-polarized supercurrent generation.

To proceed further, a quantitative estimate the magnetic inhomogeneity as a function of H is required to estimate the IC0 through the junction. According to the Houzet–Buzdin model, IC0 for a Josephson junction at a fixed temperature with a F1′FF2′ barrier is proportional to the product of the sines of the angles between adjacent magnetic layers (φ1 and φ2), that is,

Since the F layers cannot be approximated by a macrospin, it implies that we have to apply the model by calculating the product of the sine of the angle between the cells of two adjacent magnetic layers for each vertical cell stack used in the simulations within which a continuum approximation implies a uniform magnetization. The components of the magnetization in each cell are known from the OOMMF simulation and sin φ1 is obtained from the inner product of the magnetization in the ith cell of the top Py with the corresponding cell in Co. The same procedure is repeated for the ith cell of the bottom Py and Co to obtain sin φ2. The product sin φ1 × sin φ2 indicates the combined inhomogeneity arising from the three F layers (outer Py layers and the central Co layer). This procedure is repeated for each cell in the entire layer and an average value of sin φ1 × sin φ2 is obtained by summing the product for all the cells and dividing by the total number of cells. We have taken into account the actual sign of the product sin φ1 × sin φ2, since according to the Houzet–Buzdin model, the junction can be in a 0 (π) state depending on the anti-parallel (parallel) orientation of the magnetization of the outer layers. This is clear from the micromagnetic simulations shown in Fig. 3c; at low fields, local regions of the junctions are in a 0 or π state thereby reducing the total critical current through the junction. Also, the dependence of the critical current on the relative angle between two F layers reflects the fact that non-collinearity induced by inhomogeneity between two F layers is more important than inhomogeneity in a single F layer where it occurs at the scale of the magnetic exchange length, which far exceeds the coherence length of a Cooper pair in the F layer.

Figure 3b (inset) shows the dependence of IC0 on H: there are two distinct peaks (indicating maximum inhomogeneity), with the first peak at a positive field (~10 mT) related primarily to Py reversal, while the second (~−10 mT) is due to the Co layer reversal.

To calculate the phase variation owing to the local flux density B arising from a combination of the inhomogeneous barrier magnetization and H, we integrate the variation of the phase difference of the superconducting order parameter (φ) over the junction area

where λ is the penetration depth of the superconductor,  is the direction normal to the plane of the junction and e is the charge of an electron. Here, the line integral is carried out for all the points a defining the junction by starting from the origin where φ0 is defined. The critical current is finally obtained by maximizing with respect to φ0 of the surface integral defining the junction over the points a. The effective value of λ for our materials and geometry is estimated to be 90 nm (by measuring the field corresponding to one flux quantum) from devices with similar dimensions and Nb thicknesses but with Ho as the triplet generators instead of Py (Fig. 2b). Given the complex magnetization distribution in our junctions, a simple analytical solution to equation (2) is not possible and so we apply a numerical technique35 as outlined below:

is the direction normal to the plane of the junction and e is the charge of an electron. Here, the line integral is carried out for all the points a defining the junction by starting from the origin where φ0 is defined. The critical current is finally obtained by maximizing with respect to φ0 of the surface integral defining the junction over the points a. The effective value of λ for our materials and geometry is estimated to be 90 nm (by measuring the field corresponding to one flux quantum) from devices with similar dimensions and Nb thicknesses but with Ho as the triplet generators instead of Py (Fig. 2b). Given the complex magnetization distribution in our junctions, a simple analytical solution to equation (2) is not possible and so we apply a numerical technique35 as outlined below:

The local B fields obtained from the micromagnetic simulations when integrated vertically normal to the plane of the layers for the whole barrier thickness including the London penetration depth (λ) of the Nb electrodes, gives a linear flux density matrix (Cij) according to

Here z is the direction normal to the plane of the films. The Cij matrix is then converted to an equivalent matrix of phase gradients (Φij′) according to

The critical current is then obtained by performing the summations

and maximizing with respect to φ0, where φ0 is set at (1,1).

To compare our simulations with experimental data, it is necessary to know the effective coupling of the flux originating from the barrier magnetization into the junction. In an SFS junction with a single, homogeneously magnetized ferromagnetic barrier the maximum critical current is achieved when H=ΔH where

b is the effective coupling of the flux originating from the saturation magnetization of the ferromagnet M, and dFM is the thickness of the ferromagnet. We can estimate b from Nb/Ho/Co/Ho/Nb junctions with a similar size and shape: the inset to Fig. 3b in ref. 4 shows the field offset (ΔH) versus dCo and a linear fit to (ΔH versus dCo/(2*λ+dCo) (Fig. 3b inset, ref. 4) gives b=0.2. This implies a significant partial cancellation of the magnetization flux arising from fringing fields producing a flux in the opposite direction in the region within the penetration depth of the superconductor. Using b=0.2, IC calculated from equation (5) with IC0=1 is shown in Fig. 3b (inset); the distortion of an ideal Fraunhofer pattern arises due to field-dependent inhomogeneous magnetism of the barrier. Figure 3b (green curve) shows the full solution of equation (5) by including IC0(H) shown in the other inset and thus shows the combined effect of the dependence of the triplet supercurrent on the magnetic structure and the flux arising from the inhomogeneous magnetic barrier.

Discussion

Inspection of Fig. 3b shows that several features of the experimental curve are well reproduced. These include the rapid decay of IC above a critical field and the severely suppressed higher order lobes as a result of a more homogenous magnetic structure where IC0→0. The small remnant oscillations in the simulated curve arises from a residual inhomogeneity at the edges arising from dipolar fields between Py and Co layers, which always remain in the simulation but, experimentally may not contribute because of surface oxidation and intermixing arising from the ion-milling during fabrication. The dip near zero field (less prominent in the experimental curve) is quite sensitive to the magnetic configuration of each layer. At low fields, such configurations are quite prone to stochastic variations induced by factors like the film microstructure, exact device dimensions and magnetic history, and direct comparison with experiments are difficult to make in that field region. Ideally, the low and zero field configuration is expected to be symmetric with respect to the magnetic state of the outer layers and noncolinear to the central Co layer; this implies that globally the junction is in a π state and the sign of the product of sin φ1 sin φ2 is irrelevant. Taking this fact into consideration, we have simulated the same junction (Fig. 3b, brown curve). The two simulations differ only at or near zero field. This brown curve, therefore, provides an upper limit to the critical current close to zero field for a junction with homogeneously symmetric (or antisymmetric) outer Py layers.

In view of the above, the behaviour of devices with thinner Co (Fig. 2c) becomes clear: on reducing the central Co layer a background singlet current flows whose maximum value is insensitive to the magnetic state in the device and is thus visible as phase-controlled IC oscillations beyond the central lobe.

From the point of view of applications, the key aspect of this result is the experimental proof that the triplet supercurrent amplitude can be reversibly controlled by changing the magnetic inhomogeneity within the barrier. This provides direct control over the spin-polarized supercurrent, which is of fundamental importance towards the realization of practical superconducting spintronic circuits. Perhaps equally as importantly, we demonstrate that significant inhomogeneity can be generated even in nanoscale junctions and appropriate engineering of the micromagnetic structure offers the potential to optimize the response of the system to very small field changes or spin transfer torques36,37,38.

Methods

Film growth

Nb(250)/Cu(5)/Py(y)/Cu(5)/Co(x)/Cu(5)/Py(y)/Cu(5)/Nb(250) (thicknesses in nanometres) samples were grown on unheated (001) Si substrates with a 250-nm thick SiO2 coating by dc magnetron sputtering in ultra-high vacuum chamber. The base pressure was maintained below 10−8 Pa while the chamber was cooled via a liquid nitrogen jacket. The targets were pre-sputtered for 15–20 min to clean the surfaces and the films were grown in 50 mT (approximately) magnetic field by placing the substrates between two bar magnets. This induces an easy axis for the Py films along the growth-field direction. The Cu layer between the base Nb and Py was inserted to improve the magnetic properties of Py. The Co thickness (x) was varied between 3 and 9 nm.

Device fabrication

Devices were prepared with either 1.5 or 2.5 nm Py layers (y); in general, these showed similar results. Standard optical lithography and Ar-ion milling were used to define 4-μm-wide tracks, which were narrowed down by focused-ion-beam milling to make current-perpendicular-to-plane devices: details of the process are described elsewhere39. The average device dimensions were in the range of 600 × 500 nm.

Transport measurements

A custom-built liquid He dip probe was used to cool the devices down to 4.2 K by dipping it in a liquid He dewar. Current–voltage characteristics were measured by a four-point technique using a current-biased circuit attached to a lock-in amplifier. The Josephson effect in the devices was measured by applying an in-plane magnetic field and measuring the critical current IC as a function of the applied field (H) (Fig. 2a). The critical current was determined using a voltage criterion and hence a finite value is recorded even in the absence of a supercurrent. To subtract this background contribution, we have divided this criterion voltage by the normal state resistance of the junction, which shifts the effective zero critical current line to the values shown by the red dotted line in each figure. The field was applied perpendicular to the Py easy axis which gives a weak tendency of the Py to align itself perpendicular to the Co layer at low or zero external fields.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Banerjee, N. et al. Reversible control of spin-polarized supercurrents in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 5:4771 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5771 (2014).

References

Buzdin, A. I. Proximity effects in superconductor-ferromagnet heterostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 935–976 (2005).

Bergeret, F. S., Volkov, A. & Efetov, K. Odd triplet superconductivity and related phenomena in superconductor-ferromagnet structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1321–1373 (2005).

Bergeret, F. S., Volkov, A. & Efetov, K. Long-range proximity Effects in superconductor-ferromagnet structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4096–4099 (2001).

Robinson, J. W. A., Witt, J. D. S. & Blamire, M. G. Controlled injection of spin-triplet supercurrents into a strong ferromagnet. Science 329, 59–61 (2010).

Khaire, T. S., Khasawneh, M. A., Pratt, W. P. & Birge, N. O. Observation of spin-triplet superconductivity in Co-based Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 137002 (2010).

Keizer, R. S. et al. A spin triplet supercurrent through the half-metallic ferromagnet CrO2 . Nature 439, 825–827 (2006).

Anwar, M. S., Czeschka, F., Hesselberth, M., Porcu, M. & Aarts, J. Long-range supercurrents through half-metallic ferromagnetic CrO2 . Phys. Rev. B 82, 100501 (2010).

Banerjee, N. et al. Evidence for spin selectivity of triplet pairs in superconducting spin valves. Nat. Commun. 5, 3048 (2014).

Sprungmann, D., Westerholt, K., Zabel, H., Weides, M. & Kohlstedt, H. Evidence for triplet superconductivity in Josephson junctions with barriers of the ferromagnetic Heusler alloy Cu2MnAl. Phys. Rev. B 82, 060505 (2010).

Kalcheim, Y., Millo, O., Egilmez, M., Robinson, J. W. A. & Blamire, M. G. Evidence for anisotropic triplet superconductor order parameter in half-metallic ferromagnetic La0.7Ca0.3MnO3 proximity coupled to superconducting Pr1.85Ce0.15CuO4 . Phys. Rev. B 85, 104504 (2012).

Visani, C. et al. Equal-spin Andreev reflection and long-range coherent transport in high-temperature superconductor/half-metallic ferromagnet junctions. Nat. Phys. 8, 539–543 (2012).

Kalcheim, Y., Kirzhner, T., Koren, G. & Millo, O. Long-range proximity effect in La2/3Ca1/3MnO3/(100)YBa2Cu3O7-δ ferromagnet/superconductor bilayers: evidence for induced triplet superconductivity in the ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 83, 064510 (2011).

Anwar, M. S. & Aarts, J. Inducing supercurrents in thin films of ferromagnetic CrO2 . Supercond. Sci. Technol. 24, 024016 (2011).

Sosnin, I., Cho, H., Petrashov, V. & Volkov, A. Superconducting phase coherent electron transport in proximity conical ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 157002 (2006).

Usman, I. T. M. et al. Evidence for spin mixing in holmium thin film and crystal samples. Phys. Rev. B. 83, 144518 (2011).

Eschrig, M. Spin-polarized supercurrents for spintronics. Phys. Today 64, 43 (2011).

Gingrich, E. C. et al. Spin-triplet supercurrent in Co/Ni multilayer Josephson junctions with perpendicular anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 86, 224506 (2012).

Klose, C. et al. Optimization of spin-triplet supercurrent in Ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127002 (2012).

Robinson, J. W. A., Chiodi, F., Egilmez, M., Halász, G. B. & Blamire, M. G. Supercurrent enhancement in Bloch domain walls. Sci. Rep. 2, 699 (2012).

Chappert, C., Fert, A. & Van Dau, F. N. The emergence of spin electronics in data storage. Nat. Mater. 6, 813–823 (2007).

Houzet, M. & Buzdin, A. I. Long range triplet Josephson effect through a ferromagnetic trilayer. Phys. Rev. B 76, 060504 (2007).

Khaire, T., Pratt, W. & Birge, N. O. Critical current behavior in Josephson junctions with the weak ferromagnet PdNi. Phys. Rev. B 79, 094523 (2009).

Khasawneh, M. A., Khaire, T. S., Klose, C., Pratt, W. P. Jr & Birge, N. O. Spin-triplet supercurrent in Co-based Josephson junctions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 24, 024005 (2011).

Weides, M. Magnetic anisotropy in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 052502 (2008).

Kontos, T. et al. Josephson junction through a Thin ferromagnetic layer: negative coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 137007 (2002).

Robinson, J. W. A., Piano, S., Burnell, G., Bell, C. & Blamire, M. G. Critical current oscillations in strong ferromagnetic π junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 177003 (2006).

Robinson, J. W. A., Piano, S., Burnell, G., Bell, C. & Blamire, M. G. Zero to π transition in superconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor junctions. Phys. Rev. B 76, 094522 (2007).

Robinson, J. W. A., Halász, G. B., Buzdin, A. I. & Blamire, M. G. Enhanced supercurrents in Josephson junctions containing nonparallel ferromagnetic domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 207001 (2010).

Bell, C. et al. Controllable Josephson current through a pseudospin-valve structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1153 (2004).

Aziz, A. et al. Nonlinear giant magnetoresistance in dual spin valves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 237203 (2009).

Banerjee, N. et al. Thickness dependence and the role of spin transfer torque in nonlinear giant magnetoresistance of permalloy dual spin valves. Phys. Rev. B 82, 224402 (2010).

Cowburn, R. P. & Welland, M. E. Phase transitions in planar magnetic nanostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 2041 (1998).

Donahue, M. J. & Porter, D. G. OOMMF User’s guide, Version 1.0, Interagency Report NIST IR 6376 (Gaithersburg, MD (1999).

Yang, W., Lambeth, D. N. & Laughlin, D. E. Dependence of Co anisotropy constants on temperature, processing, and underlayer. J. Appl. Phys. 87, 6884–6886 (2000).

Blamire, M. G., Smiet, C. B., Banerjee, N. & Robinson, J. W. A. Field modulation of the critical current in magnetic Josephson junctions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 26, 055017 (2013).

Linder, J., Yokoyama, T. & Sudbø, A. Spin-transfer torque and magnetoresistance in superconducting spin valves. Phys. Rev. B 79, 224504 (2009).

Linder, J. & Halterman, K. Superconducting spintronics with magnetic domain walls. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1401.5806 (2014).

Braude, V. & Blanter, Y. Triplet Josephson effect with magnetic feedback in a superconductor-ferromagnet heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 207001 (2008).

Bell, C. et al. Fabrication of nanoscale heterostructure devices with a focused ion beam microscope. Nanotechnology 14, 630 (2003).

Acknowledgements

M.G.B. acknowledges funding from the UK EPSRC (EP/I038047/1) and the European Commission through an ERC Advanced Investigator Grant ‘Superspin’. J.W.A.R. acknowledges funding from the Royal Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B. prepared the samples, fabricated the devices and carried out the measurements. N.B. performed the micromagnetic simulations and together with M.G.B. carried out the finite element simulations. N.B., M.G.B. and J.W.A.R. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Banerjee, N., Robinson, J. & Blamire, M. Reversible control of spin-polarized supercurrents in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Nat Commun 5, 4771 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5771

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5771

This article is cited by

-

Chiral antiferromagnetic Josephson junctions as spin-triplet supercurrent spin valves and d.c. SQUIDs

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Coexistence and tuning of spin-singlet and triplet transport in spin-filter Josephson junctions

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Evidence for anisotropic spin-triplet Andreev reflection at the 2D van der Waals ferromagnet/superconductor interface

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Superconductivity assisted change of the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in V/MgO/Fe junctions

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Josephson Memories

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.