Abstract

The introduction of bowel cancer screening, in the United Kingdom, United States of America, and many other Western countries, has provided considerable interest and no little diagnostic consternation for pathologists. In the United Kingdom, the universal introduction of bowel cancer screening, initially by fecal occult blood testing and more recently by the introduction of flexible sigmoidoscopy, has provided four main areas of pathological diagnostic difficulty. This is the biopsy diagnosis of adenocarcinoma, serrated pathology, the diagnosis and management of polyp cancer, and, finally, the phenomenon of pseudoinvasion/epithelial misplacement (PEM), particularly in sigmoid colonic adenomatous polyps. The diagnostic difficulties associated with the latter phenomenon have provided particular problems that have led to the institution of a UK national ‘Expert Board’, comprising three pathologists, who adjudicate on difficult cases. The pathological features favoring PEM are well recognized but there is no doubt that there can be profound mimicry of adenocarcinoma, and, as yet, no adjunctive diagnostic tools have been developed to allow the differentiation in difficult cases. Research in this area is proceeding and some methodologies do show promise in this difficult diagnostic area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National bowel cancer screening was introduced in England in 2006. Similar, but not identical, programs have been developed in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland, and there are similar programs being developed, on a national basis, in other Western European countries.1 In North America, there are well-established bowel cancer screening programs, but not on a universal, national basis. Methodologies used for colorectal cancer screening are predominantly based on fecal testing and/or endoscopy. Fecal occult blood testing remains the basis for screening in England. However, a pilot scheme offering flexible sigmoidoscopy in six bowel cancer screening centers has been introduced, offered on a one-off basis between the ages of 55 and 64 years,2 to be rolled out nationally by 2016. The success of a screening program can be judged on the uptake and there is considerable variation, based on socioeconomic and ethnic factors largely, in uptake in the five countries that comprise the British Isles.

National cancer screening had been previously introduced, in the United Kingdom, for cervical and breast cancer. There had been singular controversies in these screening programs, and thus, with the establishment of bowel cancer screening, intensive quality control was introduced. Initial presumptions, as far as pathology is concerned, were that the diagnostic pathology associated with bowel cancer screening would be relatively straightforward. Nevertheless, this has shown not to be the case. The four main diagnostic areas of difficulty in bowel cancer screening (BSCP=Bowel Cancer Screening Program) pathology are:

-

1

The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma on biopsy.

-

2

Serrated pathology.

-

3

Polyp cancer diagnosis and its management.

-

4

The large adenomatous polyp of the sigmoid colon with pseudoinvasion/epithelial misplacement (PEM).

Extraordinarily, the biopsy diagnosis of adenocarcinoma has provided particular problems in the United Kingdom. This is because we still rely on the demonstration of malignant cells within the submucosa (and/or an appropriate desmoplastic reaction) to make the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. This is based on ‘Morsonesque’ (after Dr Basil Morson, the eminent UK gastrointestinal pathologist) dogma that insists that, in the United Kingdom at least, intramucosal adenocarcinoma is not an acceptable concept as this can result in surgical overtreatment. Practice, both in bowel cancer screening and outside it, has been dogged by the need for multiple biopsies because invasion into the submucosa has not been demonstrated. More recently, it has been recommended, especially for colonic cancer, that if biopsies confirm primary neoplasia (but do not necessarily demonstrate invasive malignancy) and the endoscopic and radiological evidence points to a large mass requiring surgery, then the biopsy diagnosis of definite adenocarcinoma may not be required as long as the biopsies confirm primary colorectal neoplasia.3, 4

Serrated pathology has also produced no little consternation for pathologists reporting BCSP specimens. First, as part of colorectal cancer screening, a positive fecal occult blood test is followed by colonoscopy and colonoscopists are under strict instructions to ensure that all polyps are removed. Thus, we are seeing increasing amounts of more subtle right-sided serrated pathology, providing particular diagnostic challenges. Serrated pathology is covered in an accompanying article in this series, by Dr Kenneth Batts, and the diagnostic difficulties associated with it will not be further considered here.

There is considerable overlap in the two final areas of diagnostic and management difficulty associated with BCSP. This is because of the phenomenon of PEM, particularly seen in larger sigmoid colonic adenomatous polyps, which can strongly mimic polyp cancer. Nevertheless, this does not impinge on the particular difficulties associated with the management of polyp cancers, both within and without bowel cancer screening.

The malignant polyp: is it really malignant?

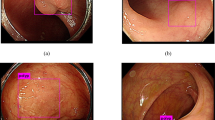

There has been considerable improvement in the diagnosis of polyp cancer endoscopically. Indeed, pathologists are aware that many of their endoscoping colleagues are confident, often based on Kudo-type classifications of ‘pit pattern’, that they can diagnose invasive malignancy. Furthermore, if EMR (endoscopic mucosal resection) or ESD (endoscopic submucosal dissection) are attempted, the tethering associated with invasive malignancy gives a guide to endoscopists as to whether or not a polyp is malignant. Nevertheless, it has to be emphasized that PEM can result in the same features, namely the mimicry of malignancy by its surface features (Figure 1) and by inducing tethering because of the PEM. Histological assessment will, seemingly, always be required to secure the appropriate diagnosis.

It has to be appreciated that even the macroscopic pathological features can mimic malignancy. Larger adenomatous polyps in the sigmoid colon are often nodular and ulcerated. In fact, with experience, they have rather particular endoscopic and macroscopic pathological features (Figure 1). Of singular importance is the fact that these polyps, showing florid PEM, are mainly in the sigmoid colon. In our experience, 85% of all of these polyps are in the sigmoid colon, with about 10% in the descending colon. PEM, in adenomatous polyps, is occasionally seen at other sites. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that the rectum is an unusual site for PEM unless there has been previous endoscopic or surgical intervention. In that situation, a very characteristic feature of PEM is the fact that both non-neoplastic and adenomatous epithelium is often misplaced into the submucosa (Figure 2). This appears to be a particular feature of PEM after previous endoscopic or surgical intervention.

A descending colonic adenomatous polyp subject to previous attempted endoscopic excision. At right and above is residual surface adenoma. In the submucosa there is misplacement of both non-neoplastic mucosa and adenomatous epithelium. This combination of pseudoinvasion/epithelial misplacement (PEM) appears to be characteristic of the effects of previous intervention, whether endoscopic or surgical.

Epithelial misplacement in intestinal polyps

Recognized now for many years, the characteristic syndrome in which PEM is seen is Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. The association of mucocutaneous pigmentation with ‘hamartomatous’ polyps is a rare syndrome, afflicting about 1 in 100 000 people in Western countries. It is associated with hereditary genetic mutation of the STK1 gene and the syndrome results in polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract and in the nasopharynx and urinary system. They are most common in the small intestine. Presumably because of the caliber and motor activity of the small intestine, larger polyps are subject to intussusception and it is likely that this is the mechanism whereby PEM occurs. PEM in the small intestinal Peutz-Jeghers polyps can often be significant and can involve all layers of the bowel wall, including the subserosal tissues, where mucus cysts may be seen.5 This results in profound mimicry of malignancy, despite the fact that the epithelium is either normal or slightly hyperplastic, rather than dysplastic, and it has been mooted that the high rates of the small intestinal carcinoma, in particular, complicating Peutz–Jeghers syndrome can be attributed to the misdiagnosis of PEM in the earlier literature.5, 6 More recently, misplacement of dysplastic epithelium in Peutz–Jeghers polyps has been described, further heightening the diagnostic difficulties.7

PEM is especially seen in polypoid mucosal prolapse, characteristically in the so-called inflammatory cloacogenic polyp at the ano-rectal junction, but it is also seen elsewhere, in association with diverticulosis, at stomas, and in the solitary ulcer (mucosal prolapse) syndrome. In all of these situations, PEM, whether enteritis cystica profunda, colitis cystica profunda, or proctitis cystica profunda, can result in PEM and the potential overdiagnosis of cancer. PEM is also seen in serrated pathology. It may be seen in small hyperplastic polyps in the left colon and rectum, but is a particular feature, often through lymphoglandular complexes, in sessile serrated lesions (known as sessile serrated polyps/adenomas in the United States of America) of the right colon. These have been termed inverted hyperplastic polyps.8, 9 In adenomatous polyps of the colon, PEM can also be seen in and through lymphoglandular complexes as these provide a microanatomical defect in the muscularis mucosae.

PEM was first described in adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum by Muto et al,10 including Dr Basil Morson. They noted that this was the particular feature of larger polyps in the sigmoid colon and it was recognized that there were particular morphological features associated with PEM. First, the adenomatous epithelium in the submucosa appears similar, cytologically, to the surface adenomatous epithelium and is usually accompanied by lamina propria (Figure 3). Hemosiderin deposition is characteristic because a perceived mechanism of PEM is epithelial necrosis and subsequent hemorrhage (Figure 3). Mucus lakes are also a characteristic feature.

More recently, we recognize particular features associated with PEM. In three dimensions, there appears to be continuity of the epithelium with the surface epithelium with similar cytology and architecture (Figure 4). As mucosal prolapse may be a mechanism, muscular proliferation and pathological mucosal prolapse changes are common (Figure 5). There may also be evidence of acute necrosis of the surface of the adenomatous polyp, underpinning the perceived pathogenic mechanisms of epithelial misplacement. On the other hand, isolated glands without accompanying lamina propria, budding, vascular invasion, and poor differentiation are all features that, clearly, favor adenocarcinoma.

This sigmoid colonic adenomatous polyp shows features typical of pseudoinvasion/epithelial misplacement (PEM) (at lower aspect), but the intervening glands (marked by a pathologist with familiar black dots!!) are more isolated. However, if one tries to imagine these in three dimensions, then one can envisage continuity between the more isolated glands and those on the surface.

As far as bowel cancer screening is concerned, patients with these larger sigmoid colonic adenomatous polyps are preferentially selected into screening because the primary screening modality is fecal occult blood and these larger polyps bleed. In the United Kingdom, at least, the diagnostic difficulties associated with PEM versus adenocarcinoma have led to the establishment of a BCSP Expert Board. There are three specialist gastrointestinal pathologists in the Board, largely because a diagnostic majority is required for this high subjective and difficult assessment. The experience of the Expert Board is that universal agreement between three highly experienced gastrointestinal pathologists is not necessarily forthcoming because of the diagnostic difficulties. Table 1 gives the summary of the current status of the Expert Board assessments.

Diagnostic adjuncts in PEM versus carcinoma

As indicated previously, PEM is particularly associated with continuity of the epithelium between superficial and deep components (Figure 4). This is a little difficult to appreciate in two-dimensional slides, but an important part of the diagnostic process is for pathologists to undertake deeper levels through the blocks. This can aid in the three-dimensional assessment of such polyps. More recently, we have undertaken computerized three-dimensional reconstruction and have demonstrated singular continuity between the superficial and deep components of PEM. However, our analyses, both subjective assessment of videos and mathematical modeling of continuity, have demonstrated that early polyp cancers may also show such continuity and there is no definitive differentiation of PEM and early polyp cancers using three-dimensional reconstruction. In a small series of cases, we have applied infrared spectroscopic methodology in an attempt to differentiate PEM from polyp cancers. This method does show some promise and current work is directed at analyzing large series of PEM and polyp cancer, by infrared spectroscopic methods, to see if this will aid the diagnostic process.

Earlier papers attest to the use of immunohistochemistry in differentiating PEM from invasive carcinoma.11 Workers from Boston, USA have suggested that MMP-1, p53, collagen IV, and e-cadherin (Figure 6) can aid in the distinction between PEM and carcinoma. It is our view, and that of other workers including the original authors (RK Yantiss, personal communication), that these immunohistochemical methods work very well in classical PEM and classical polyp cancer but are not particularly helpful in difficult cases. This is certainly the experience in the United Kingdom.

E-cadherin immunohistochemistry in a sigmoid colonic adenomatous polyp with pseudoinvasion/epithelial misplacement (PEM). The prominent staining at right identifies adenomatous epithelium accompanied by lamina propria with a focus of PEM. There is a notable reduction in staining in the more dissociated epithelium towards the left. This was interpreted as PEM. E-cadherin is one of the better immunohistochemical markers in these cases, but experience has indicated that it may not be helpful in the most difficult cases.

In summary, PEM in large sigmoid colonic adenomatous polyps, within bowel cancer screening, has become the most extraordinary diagnostic conundrum that a senior gastrointestinal pathologist has seen, or perhaps recognized, in his professional career. We have seen low levels of interobserver agreement among general pathologists12 and certainly not perfect interobserver agreement between experts. This phenomenon is surely only matched by the subjective diagnostic difficulties associated with melanocytic lesions of the skin.

Polyp cancers and their management

One of the principles of bowel cancer screening is that there is a stage shift, compared with symptomatic colorectal cancer, with much higher proportions of early cancers. Indeed, results from BCSP have indicated that about half of all cancers detected in bowel cancer screening are either stage 1/Dukes A or alternatively polyp cancers. The current proportion of pT1 cancers in BCSP is about 17%. Given the management conundra associated with polyp cancers, bowel cancer screening has introduced very considerable management debates in this difficult area. This particularly pertains to the recommendations for resection after the removal of a polyp cancer.

What, then, are the risk factors for adenomas undergoing malignant change? Size, villosity, and high-grade dysplasia are all important,13 but it is also apparent that site is important. In one study, 6.4% of right colonic adenomas showed malignant change and 8.0% of left-sided colonic adenomas showed malignancy, whereas 23% of rectal adenomas showed malignancy.13 In terms of the pathological assessment, for many years pathologists have relied on the ‘Cooper criteria’ to make a judgment about further management.14 Poorly differentiated carcinoma, vascular invasion, and margin involvement (Figure 7) are all regarded as adverse prognostic features that may demand subsequent resection. Logic dictates that vascular invasion and poor differentiation are adverse prognostic parameters and there is good literature evidence for this. On the other hand, there appears to be less logic for margin involvement being an important adverse prognostic parameter. Nevertheless, certainly the literature indicates that margin involvement is the most predictive parameter for adverse prognosis.14, 15, 16

A polyp cancer. The tumor seen here is poorly differentiated and there is obvious lymphovascular spread. Margin involvement was also present. The three ‘chief’ adverse prognostic parameters in polyp cancers are all present and resection was undertaken. There was extensive mesocolic lymph node involvement in that resection specimen.

In terms of recommendations for further management, perhaps the most reliable evidence is provided by a pooled-data analysis of polyp cancers from 2005.17 In this assessment of all ‘colorectal malignant polyps in the literature’, a positive margin of resection is predictive of residual disease, recurrent disease, hematogenous metastasis, and mortality. On the other hand, poor differentiation is only predictive of lymph node metastasis, hematogenous metastasis, and mortality, whereas vascular invasion only predicts lymph node metastasis. Thus, despite positive margin of resection predicting adverse results, an important issue is the fact that, in this pooled-data analysis anyway, it did not appear to predict lymph node metastatic disease. Experience has indicated that the one feature that subsequent surgical resection will identify and potentially treat/cure is lymph node metastatic disease. Thus, the data from this pooled-data analysis, at least, may not too strongly support surgical resection for a polyp cancer showing only margin involvement, despite the fact that positive margin may be predictive of an adverse prognosis. One especial difficulty concerning margin involvement is that many papers fail to define adequately margin involvement histologically.

Even vascular invasion in polyp cancers is controversial. There are two publications, both from the United Kingdom and published within 2 years of each other, which indicate that, on the one hand, vascular invasion is a significant predictor of metastasis,18 whereas, in a second study, in a large series of 81 polyp cancers, vascular invasion had no prognostic value.15

The Haggitt classification is a time-honored and widely promulgated system for prognostication in polyp cancers. Rodger Haggitt introduced five ‘levels’ and indicated that level IV, invasion beyond the stalk but above the muscularis propria, into the neck of the polyp, was associated with significant adverse prognosis.19 The Haggitt classification is still widely used for polyp cancers but, in the United Kingdom at least, it is associated with very considerable interobserver variability and is of less certain efficacy for patient management. In a similar manner, the Kikuchi methodology, which divides submucosal involvement into three layers (in the original Kikuchi study, sm1 was associated with a 0% lymph node metastatic rate, sm2 with a 5% rate, and sm3 with a 22% rate), is associated with problems, especially interobserver variation and difficulty of application because in many polyp cases no muscular propria is present, making it difficult to stage and/or measure the submucosal involvement.20 Further, the Kikuchi methodology is usually only applied to, and applicable for, sessile polyps, rather than pedunculated polyps.20

The subsequent management of polyp cancers

Whether or not to recommend surgical resection after the endoscopic removal of a polyp cancer requires an assessment of the balance between the risk of metastatic disease and the risk of surgery. Margin involvement in a polyp cancer is the most common adverse prognostic feature and is most likely to be isolated without evidence of either vascular invasion or poor differentiation. Given the conundra described above, margin involvement has become a highly controversial indicator for subsequent surgery. We firmly believe that it is critical that all such polyp cancers are discussed in a Multi-disciplinary Team Meeting and that other factors, perhaps particularly age and comorbidity, are brought into the discussion. Other high-risk factors to consider are poor differentiation, lymphovascular invasion, Kikuchi level sm3, Haggitt IV, sessile lesions with a width >30 mm, tumor budding, and depth of spread. All of these assessments are subjective and associated with interobserver variation. However, there is no doubt that measuring the depth and width of invasion is predictive of lymph node metastatic disease.21, 22

There has now been considerable work on tumor budding as an adverse prognostic parameter in colorectal cancer.21, 23, 24 There are certainly varying methods of assessment and tumor heterogeneity and reproducibility are considerable problems with tumor budding. Nevertheless, it is an adverse prognostic parameter in polyp cancers21 and it is likely that tumor budding will be recommended for usage in determining prognosis, and subsequent surgery, in polyp cancers in the future. It is emphasized that so many of these pathological assessments are associated with relatively poor interobserver agreement. Indeed, in a recent study undertaken in the United Kingdom, involving 10 expert gastrointestinal pathologists, many of these pathological assessments were associated with poor interobserver agreement. The one area where there was good interobserver agreement was in measurement. Thus, in the United Kingdom at least, research indicates that depth and width of polyp cancer may become the most useful prognostic and management determinants.

Summary

There is no doubt that the introduction of population-wide colorectal cancer screening has driven up overall colorectal pathology reporting quality by the introduction of standards, changes in practice, external quality review, and the use of performance indicators and quality measures. As part of that screening, polyp cancers and their mimics provide huge consternation for pathologists, clinicians, and patients. We firmly believe that bowel cancer screening programs will provide answers for the very difficult areas of management of polyp cancers. Nevertheless, mortality data on large screening populations will not be available for some time and we rely on the most important surrogate marker for cancer-related mortality, namely pathological staging. This emphasizes the importance of exemplary quality pathology, of polyps, polyp cancers, and resection specimens, in bowel screening programs.2, 3, 4 At the current time, margin involvement in polyp cancers provides particular issues in terms of its definition and implication. Measuring the width and depth of polyp cancers, together with budding, may provide the answers for management decisions in malignant polyps. Even so, the management of such polyps is best discussed in a Multidisciplinary Team Meeting, which brings into play all factors of relevance for further management.

References

Benson VS, Patnick J, Davies AK et al. Colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of 35 initiatives in 17 countries. Int J Cancer 2008;122:1357–1367.

Public Health England. NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme 2013, Available at:http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/bowel/index.html; last accessed on 15 June 2014.

Carey F, Newbold M, Quirke P et al. Reporting lesions in the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme: Guidelines from the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme Pathology Group. 2007;1–24.

Loughrey MB, Quirke P, Shepherd NA, Dataset and Reporting Guidelines for Colorectal Cancer, Royal College of Pathologists, 3rd edn. Available at: http://www.rcpath.org/Resources/RCPath/Migrated%20Resources/Documents/G/G049_ColorectalDataset_July14.pdf. Last accessed on 22 October 2014.

Shepherd NA, Bussey HJ, Jass JR . Epithelial misplacement in Peutz–Jeghers polyps. A diagnostic pitfall. Am J Surg Pathol 1987;11:743–749.

Bartholomew LG, Dahlin DC, Waugh JM . Intestinal polyposis associated with mucocutaneous melanin pigmentation Peutz–Jeghers syndrome; review of literature and report of six cases with special reference to pathologic findings. Gastroenterology 1957;32:434–451.

Petersen VC, Sheehan AL, Bryan RL et al. Misplacement of dysplastic epithelium in Peutz–Jeghers polyps: the ultimate diagnostic pitfall? Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:34–39.

Sobin LH . Inverted hyperplastic polyps of the colon. Am J Surg Pathol 1985;9:265–272.

Yantiss RK, Goldman H, Odze RD . Hyperplastic polyp with epithelial misplacement (inverted hyperplastic polyp): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Mod Pathol 2001;14:869–875.

Muto T, Bussey H, Morson B . Pseudo-carcinomatous invasion in adenomatous polyps of colon and rectum. J Clin Pathol 1973;26:25–31.

Yantiss R, Bosenberg M, Antonioli D et al. Utility of MMP-1, p53, E-cadherin, and collagen IV immunohistochemical stains in the differential diagnosis of adenomas with misplaced epithelium versus adenomas with invasive adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:206–215.

Turner JK, Williams GT, Morgan M et al. Interobserver agreement in the reporting of colorectal polyp pathology among bowel cancer screening pathologists. Histopathology 2013;62:916–924.

Nusko G, Mansmann U, Altendorf-Hofmann A et al. Risk of invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas assessed by size and site. Int J Colorectal Dis 1997;12:267–271.

Cooper HS, Deppisch LM, Gourley WK et al. Endoscopically removed malignant colorectal polyps: clinicopathologic correlations. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1657–1665.

Geraghty JM, Williams CB, Talbot IC . Malignant colorectal polyps: venous invasion and successful treatment by endoscopic polypectomy. Gut 1991;32:774–778.

Geboes K, Ectors N, Geboes KP . Pathology of early lower GI cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005;19:963–978.

Hassan C, Zullo A, Risio M et al. Histologic risk factors and clinical outcome in colorectal malignant polyp: a pooled-data analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1588–1596.

Muller S, Chesner IM, Egan MJ et al. Significance of venous and lymphatic invasion in malignant polyps of the colon and rectum. Gut 1989;30:1385–1391.

Haggitt RC, Glotzbach RE, Soffer EE et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in adenomas: implications for lesions removed by endoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology 1985;89:328–336.

Kikuchi R, Takano M, Takagi K et al. Management of early invasive colorectal cancer. Risk of recurrence and clinical guidelines. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:1286–1295.

Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y et al. Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;127:385–394.

Matsuda T, Fukuzawa M, Uraoka T et al. Risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with pedunculated type early invasive colorectal cancer: a retrospective multicenter study. Cancer Sci 2011;102:1693–1697.

Wang LM, Kevans D, Mulcahy H et al. Tumor budding is a strong and reproducible prognostic marker in T3N0 colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:134–141.

Lugli A, Karamitopoulou E, Zlobec I . Tumour budding: a promising parameter in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1713–1717.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shepherd, N., Griggs, R. Bowel cancer screening-generated diagnostic conundrum of the century: pseudoinvasion in sigmoid colonic polyps. Mod Pathol 28 (Suppl 1), S88–S94 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.138

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2014.138