Abstract

Oral leukoplakia is a relatively common, painless disorder of the oral mucosa. It predominantly affects middle-aged to elderly men and has a strong association with tobacco smoking and alcohol intake. Concomitant histological findings of hyperorthokeratosis and a well-developed granular cell layer, termed orthokeratotic dysplasia, are often associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma. In contrast, analogous lesions within the esophagus, termed esophageal epidermoid metaplasia, are rarely encountered and poorly described in the literature. To better characterize the clinicopathological features of this entity, we have collected 25 cases from 18 patients. Patients ranged in age from 37 to 81 years (mean, 61.5 years), with a slight female predominance (10/18, 56%). On presentation, a majority of patients complained of dysphagia (10/18, 56%). Past medical history was significant for tobacco smoking or long history of second-hand smoke in 11 (61%) patients and alcohol intake in 7 (39%) patients. Seventeen (94%) patients with esophageal epidermoid metaplasia were located within the middle-to-distal esophagus. Histologically, all cases were sharply demarcated and characterized by epithelial hyperplasia, a thickened basal layer, acanthotic midzone, a prominent granular cell layer, and superficial hyperorthokeratosis. Adjacent high-grade squamous dysplasia and/or squamous cell carcinoma were seen in 3 out of 18 (17%) patients. Follow-up information was available for 13 out of 18 (72%) patients and ranged from 2 to 8.3 years (mean, 2.3 years). Seven of the 13 (54%) patients had persistent disease; however, none of them developed squamous dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma. In an effort to assess the incidence of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia, 198 consecutive esophageal biopsies were prospectively surveyed over a 6-month period at three academic institutions. No cases were identified within this time frame. In summary, esophageal epidermoid metaplasia is a rare condition affecting the middle-to-distal esophagus in middle-aged to elderly females. The occurrence of adjacent high-grade squamous dysplasia and/or squamous cell carcinoma warrants close follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Leukoplakia is a clinical term used to indicate a white patch or plaque occurring on the surface of mucous membranes that cannot be rubbed off and cannot be characterized clinically as any other disease.1, 2 Within the oral cavity, leukoplakia is a relatively common, painless finding of the oral mucosa. It predominantly affects middle-aged to elderly men and has a strong association with tobacco smoking and alcohol intake.3, 4 The World Health Organization considers it to be one of the most common premalignant or potentially malignant disorders and a risk factor for progression to squamous cell carcinoma.1, 2

In addition to the oral cavity, leukoplakia of the esophagus has also been reported. However, esophageal leukoplakia is rare with six cases observed in a series of 1000 autopsy specimens of the esophagus.5 In a study by Taggart et al6, risk factors for esophageal leukoplakia were similar to those of oral leukoplakia. Patients had significantly greater history of alcohol consumption, head and neck pathology (squamous cell carcinoma/dysplasia, leukoplakia, and lichen planus), esophageal squamous dysplasia, and/or squamous cell carcinoma. Thus, it seems that esophageal leukoplakia may parallel its oral counterpart in terms of risk factors and preneoplastic potential.

Recently, Kobayashi et al7 reported a histopathological review of oral leukoplakia lesions. The authors identified a subset of cases characterized by hyperorthokeratosis and a well-developed granular layer. These lesions were termed orthokeratotic dysplasia and often associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma. In contrast, similar lesions within the esophagus termed esophageal epidermoid metaplasia are rarely encountered and poorly described within the literature. To better understand and assess the clinical behavior and histological features of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia, we have collected biopsies from 18 patients and have described the patient demographics, endoscopic findings, histomorphology, and clinical outcome.

Materials and methods

A total of 25 esophageal biopsy specimens displaying hyperorthokeratosis and a prominent granular cell layer (esophageal epidermoid metaplasia) were collected from 18 patients between 2003 and 2013 from Johns Hopkins Hospital, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Mercy Medical Center of Des Moines, IA, Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, AZ, and George Washington Hospital. These included 8 cases seen in consultation by one of the authors (EAM) and 17 routine cases. Patient demographic data, endoscopic reports, and follow-up information were recorded. Clinically significant tobacco smoking and alcohol intake were defined as >10 pack year history and >2 drinks per day, respectively. Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slides were evaluated for each specimen. In addition, we prospectively sought to identify additional cases within a time period of 6 months from three academic medical institutions: George Washington Hospital, Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, AZ, and Ohio State University. No cases of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia were identified among 198 consecutive esophageal biopsies from 183 patients. In addition, when available, patient demographic information including sex, age, tobacco smoking, and alcohol intake for this control group were recorded.

Results

The clinical and endoscopic findings are summarized in Table 1. Patients at diagnosis ranged in age from 37 to 81 years (mean, 61.5 years; median, 60 years), with a slight predominance in females (10 out of 18, 56%). On initial clinical presentation, the majority of patients complained of dysphagia (10 out of 18, 56%), whereas the remaining presented with gastroesophageal reflux (n=4), achalasia (n=1), melena (n=1), hematochezia (n=1), and surveillance for high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s mucosa (n=1). Past medical history was significant for tobacco smoking or long history of second-hand smoke in 11 (61%) patients, alcohol intake in 7 (39%) patients, and oral and esophageal lichen planus in 2 (11%) patients. None of the patients had a history of oral leukoplakia. Endoscopic data were available for 17 out of 18 (94%) patients. Cases of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia were described as white-to-tan patches of villiform and plaque-like mucosa (Figure 1). The lesions ranged in size from 1 to 10 cm in greatest dimension (mean, 2.6 cm) and located within the middle-to-lower third of the thoracic esophagus.

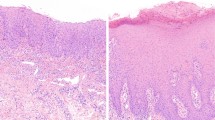

Twenty-five biopsy specimens from all 18 patients were available for review and showed common histological features (Figure 2). In each case, the lesion was sharply demarcated from the uninvolved esophageal mucosa. The squamous mucosa had an undulating appearance with flattening of the rete pegs. The basal cell layer was thickened and the midzone showed moderate acanthosis. All specimens were characterized by a prominent granular layer of 1–4 cells thick. In addition, the squamous mucosa was surmounted by varying degrees of compact hyperorthokeratosis. In many lesions, a layer of parakeratosis was present between the hyperorthokeratosis and hypergranulosis. Squamous atypia and dysplasia was distinctly absent in all cases. However, high-grade squamous dysplasia (n=2) and squamous cell carcinoma (n=1) were seen in nearby biopsies (within 2 cm of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia) in 3 out of 18 (17%) patients. In addition, basal crypt dysplasia in Barrett’s mucosa was identified in one case.

At low magnification, esophageal epidermoid metaplasia is characterized by an undulating squamous mucosa (a) with flattening of the epithelial rete pegs (b). Lesions are composed of a prominent granular layer and an overlying, compact hyperorthokeratotic layer (c). An abrupt transition is seen between esophageal epidermoid metaplasia and uninvolved squamous mucosa with focal areas of parakeratosis (d) between the hypergranulosis and hyperorthokeratosis.

Follow-up information including repeat biopsies (because of the uncertain significance of epidermoid metaplasia) was available for 13 out of 18 (72%) patients and ranged from 2 months to 8.3 years (mean, 2.3 years). Of the two patients with high-grade squamous dysplasia, one patient was rebiopsied 2 months later and found to have squamous cell carcinoma. Both patients with squamous cell carcinoma underwent esophagectomy with no evidence of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia, dysplasia, or recurrent carcinoma, 2 and 12 months thereafter. The patient with high-grade squamous dysplasia had an endoscopic mucosal resection, which included areas of epidermoid metaplasia. However, no evidence of epidermoid metaplasia, dysplasia, or carcinoma was seen 2 months on follow-up endoscopy. Of the remaining 10 patients, 7 had persistent esophageal epidermoid metaplasia on repeat biopsy that ranged from 1 to 8.3 years (mean, 2.9 years), but none of them developed squamous dysplasia or carcinoma.

To assess the incidence and demographic associations of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia, 198 consecutive esophageal biopsies from 183 patients were prospectively surveyed over a 6-month period at three academic institutions. Patients ranged in age from 20 to 87 years (mean, 55.7 years; median, 57 years), with a slight male predominance (53%). Tobacco smoking and alcohol history was available for 117 out of 183 (64%) patients. A significant history of tobacco and second-hand smoking was identified in 30 (26%) patients, and alcohol intake in 17 (15%) patients. No cases of epidermoid metaplasia were identified within this time frame.

Discussion

As reported by Kobayashi et al,7 oral orthokeratotic dysplasia is a rare histological correlate to oral leukoplakia that predominantly affects middle-aged to elderly men. In contrast to oral leukoplakia, the majority of patients are non-smokers with no predilection for alcohol abuse. The histological findings are distinct and characterized by a hyperorthokeratotic focus and a prominent granular layer. More importantly, it is often associated with malignant foci, especially oral squamous cell carcinoma. Analogous lesions within the esophagus are rare and affect the same age group. However, esophageal epidermoid metaplasia differs from oral orthokeratotic dysplasia in female predominance, associated symptoms, such as dysphagia, and risk factors including tobacco smoking and alcohol intake. Similar to its oral counterpart, esophageal epidermoid metaplasia is frequently found adjacent to high-grade squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma.

Esophageal epidermoid metaplasia was initially described as a case report by Nakanishi et al8 The authors identified white, well-demarcated areas within the distal esophagus. Histologically, these areas showed hyperorthokeratosis and hypergranulosis and were termed ‘epidermization’ of the esophageal mucosa. Adjacent to these lesions was a superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Fukui et al9 also reported a case in a patient with history of lower pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. The association with squamous cell carcinoma was further underscored in a small series by Ezoe et al10, who identified four patients with esophageal epidermoid metaplasia. All of the patients had either synchronous or metachronous squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus and oropharynx. Consistent with these findings, 3 out of 18 (17%) patients described herein were found to have either high-grade squamous dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma.

The high rate of adjacent squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma suggests that esophageal epidermoid metaplasia is a preneoplastic lesion. Considering the histological parallels and comparative clinical sequelae between oral orthokeratotic dysplasia and esophageal epidermoid metaplasia, studies on orthokeratotic dysplasia may help clarify whether its esophageal counterpart represents a precancerous condition. In fact, Aida et al7, 11 have recently demonstrated that epithelial cells within orthokeratotic dysplasia lesions undergo telomere attrition. The authors also showed that there was an increased frequency of anaphase bridges present within these lesions as compared with uninvolved squamous mucosa. Although these results do not definitively prove that oral orthokeratotic dysplasia or esophageal epidermoid metaplasia is neoplastic, these lesions are genomically unstable and may have premalignant potential.

The etiology of esophageal epidermoid metaplasia currently remains unknown. Fukui et al9 hypothesized that it develops as an unusual response to chronic irritation caused by reflux of gastric acid. However, only 22% of the lesions within our study presented with gastroesophageal reflux disease. In addition, in the case series by Ezoe et al,10 none of their patients had reflux.9 Instead, all of the patients were documented to consume excessive amounts of alcohol. Although alcohol abuse was identified in 39% of our cases, tobacco smoking and second-hand smoke were more significant findings that included 61% of patients. No mention of smoking history was reported by Enzo et al.10

Regardless of the origin, the strong association between esophageal epidermoid metaplasia and squamous dysplasia and carcinoma highlights the importance of properly recognizing this entity. Although the histological features of hyperorthokeratosis and hypergranulosis are both unique and distinct, these findings may be overlooked as injury-related, such as those due to chemical or physical agents. Principally, the differential diagnosis would include pill-induced esophagitis, corrosive damage, and sloughing esophagitis. Pill-induced esophagitis can occur at any age, but seems to be more frequent in older adults, especially in women.12, 13, 14 Common agents include antibiotics (eg, doxycycline), ferrous sulfate, alendronate sodium, and others.13, 14 The istological features are nonspecific, but in contrast to epidermoid metaplasia, often show necrosis of the squamous epithelium, spongiosis, eosinophilic infiltration, and a reactive basal layer. In some cases, pill fragments may be evident. Like pill-induced esophagitis, corrosive or caustic esophageal injury does not result in a specific pattern of injury and must be correlated with ingestion history.15 Acid injury produces coagulative necrosis of the mucosa that at low magnification can be reminiscent of the compact hyperorthokeratosis of epidermoid metaplasia. Alkaline agents typically result in liquefactive necrosis with fat and protein digestion. Lastly, sloughing esophagitis is likely due to contact injury in debilitated patients on multiple medications.16 It has a characteristic two-toned appearance consisting of squamous mucosa with a superficial eosinophilic zone containing pyknotic nuclei that resemble parakeratosis in the skin and an underlying reactive basal layer.

In summary, esophageal epidermoid metaplasia is a rare histological correlate to esophageal leukoplakia that involves the middle-to-distal esophagus and predominantly affects middle-aged to elderly females with dysphagia. Risk factors include tobacco smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Although it cannot be definitively categorized as a preneoplastic condition, recognition of this entity warrants strict surveillance for squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Adequate follow-up should not only focus on the endoscopic areas of leukoplakia, but also include the surrounding background mucosa.

References

Gale N, Westra WH, Pilch BZ . Epithelial precursor lesions In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (eds) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC Press: Lyon, 2005, pp 177–179.

Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I . Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med 2007;36:575–580.

Jaber MA, Porter SR, Gilthorpe MS et al. Risk factors for oral epithelial dysplasia--the role of smoking and alcohol. Oral Oncol 1999;35:151–156.

Jaber MA, Porter SR, Scully C et al. The role of alcohol in non-smokers and tobacco in non-drinkers in the aetiology of oral epithelial dysplasia. Int J Cancer 1998;77:333–336.

Postlethwait RW, Musser AW . Changes in the esophagus in 1,000 autopsy specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1974;68:953–956.

Taggart MW, Rashid A, Abraham SC . Esophageal leukoplakia: risk factors and relationship to squamous neoplasia. Mod Pathol 2010;23:170A (Abstract 749).

Kobayashi T, Maruyama S, Abe T et al. Keratin 10-positive orthokeratotic dysplasia: a new leucoplakia-type precancerous entity of the oral mucosa. Histopathology 2012;61:910–920.

Nakanishi Y, Ochiai A, Shimoda T et al. Epidermization in the esophageal mucosa: unusual epithelial changes clearly detected by Lugol's staining. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:605–609.

Fukui T, Sakurai T, Miyamoto S et al. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: epidermal metaplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21:1627.

Ezoe Y, Fujii S, Muto M et al. Epidermoid metaplasia of the esophagus: endoscopic feature and differential diagnosis. Hepatogastroenterology 2011;58:809–813.

Aida J, Kobayashi T, Saku T et al. Short telomeres in an oral precancerous lesion: Q-FISH analysis of leukoplakia. J Oral Pathol Med 2012;41:372–378.

Parfitt JR, Driman DK . Pathological effects of drugs on the gastrointestinal tract: a review. Hum Pathol 2007;38:527–536.

Abraham SC, Cruz-Correa M, Lee LA et al. Alendronate-associated esophageal injury: pathologic and endoscopic features. Mod Pathol 1999;12:1152–1157.

Abraham SC, Yardley JH, Wu TT . Erosive injury to the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients receiving iron medication: an underrecognized entity. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1241–1247.

Ramasamy K, Gumaste VV . Corrosive ingestion in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:119–124.

Purdy JK, Appelman HD, McKenna BJ. . Sloughing esophagitis is associated with chronic debilitation and medications that injure the esophageal mucosa. Mod Pathol 2012;25:767–775.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singhi, A., Arnold, C., Crowder, C. et al. Esophageal leukoplakia or epidermoid metaplasia: a clinicopathological study of 18 patients. Mod Pathol 27, 38–43 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.100

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.100

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Esophagitis unrelated to reflux disease: current status and emerging diagnostic challenges

Virchows Archiv (2018)

-

Early esophageal cancer with epidermization diagnosed and treated with endoscopic resection

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2018)

-

Targeted next-generation sequencing supports epidermoid metaplasia of the esophagus as a precursor to esophageal squamous neoplasia

Modern Pathology (2017)