Abstract

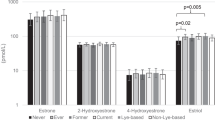

Use of personal care products is widespread in the United States but tends to be greater among African Americans than whites. Of special concern is the possible hazard of absorption of chemicals with estrogenic activity (EA) or anti-EA (AEA) in these products. Such exposure may have adverse health effects, especially when it occurs during developmental windows (e.g., prepubertally) when estrogen levels are low. We assessed the ethanol extracts of eight commonly used hair and skin products popular among African Americans for EA and AEA using a cell proliferation assay with the estrogen sensitive MCF-7:WS8 cell line derived from a human breast cancer. Four of the eight personal care products tested (Oil Hair Lotion, Extra-dry Skin Lotion, Intensive Skin Lotion, Petroleum Jelly) demonstrated detectable EA, whereas three (Placenta Hair Conditioner, Tea-Tree Hair Conditioner, Cocoa Butter Skin Cream) exhibited AEA. Our data indicate that hair and skin care products can have EA or AEA, and suggest that laboratory studies are warranted to investigate the in vivo activity of such products under chronic exposure conditions as well as epidemiologic studies to investigate potential adverse health effects that might be associated with use of such products.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Business.com Inc. Beauty and personal care products industry overview, 2011. Available at http://www.business.com/guides/beauty-and-personal-care-products-industry-overview-21128/ (cited 4 September 2012).

Boxall AB, Rudd MA, Brooks BW, Caldwell DJ, Choi K, Hickmann S et al. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: what are the big questions? Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 1221–1229.

Daughton CG, Ternes TA . Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: agents of subtle change? Environ Health Perspect 1999; 107 (Suppl 6): 907–938.

Brausch JM, Rand GM . A review of personal care products in the aquatic environment: environmental concentrations and toxicity. Chemosphere 2011; 82: 1518–1532.

Murray KE, Thomas SM, Bodour AA . Prioritizing research for trace pollutants and emerging contaminants in the freshwater environment. Environ Pollut 2010; 158: 3462–3471.

Lapworth DJ, Baran N, Stuart ME, Ward RS . Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: a review of sources, fate and occurrence. Environ Pollut 2012; 163: 287–303.

Coogan MA, Edziyie RE, La Point TW, Venables BJ . Algal bioaccumulation of triclocarban, triclosan, and methyl-triclosan in a North Texas wastewater treatment plant receiving stream. Chemosphere 2007; 67: 1911–1918.

Felner EI, White PC . Prepubertal gynecomastia: indirect exposure to estrogen cream. Pediatrics 2000; 105: E55.

Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, Bloch CA . Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. New Engl J Med 2007; 356: 479–485.

James-Todd T, Terry MB, Rich-Edwards J, Deierlein A, Senie R . Childhood hair product use and earlier age at menarche in a racially diverse study population: a pilot study. Ann Epidemiol 2011; 21: 461–465.

López-Carrillo L, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Calafat AM, Torres-Sánchez L, Galván-Portillo M, Needham LL et al. Exposure to phthalates and breast cancer risk in northern Mexico. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 539–544.

Tiwary CM . Premature sexual development in children following the use of estrogen- or placenta-containing hair products. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1998; 37: 733–739.

Wise LA, Palmer JR, Reich D, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L . Hair relaxer use and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175: 432–440.

Tiwary CM, Ward JA . Use of hair products containing hormone or placenta by US military personnel. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2003; 16: 1025–1032.

Tiwary CM . A survey of use of hormone/placenta-containing hair preparations by parents and/or children attending pediatric clinics. Mil Med 1997; 162: 252–256.

Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Bishop AM, Needham LL . Urinary concentrations of four parabens in the U.S. population: NHANES 2005-2006. Environ Health Perspect 2010; 118: 679–685.

Silva MJ, Barr DB, Reidy JA, Malek NA, Hodge CC, Caudill SP et al. Urinary levels of seven phthalate metabolites in the U.S. population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2000. Environ Health Perspect 2004; 112: 331–338.

Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA . Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 935–943.

Olson AC, Link JS, Waisman JR, Kupiec TC . Breast cancer patients unknowingly dosing themselves with estrogen by using topical moisturizers. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: e103–e104.

Boberg J, Taxvig C, Christiansen S, Hass U . Possible endocrine disrupting effects of parabens and their metabolites. Reprod Toxicol 2010; 30: 301–312.

Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Chung KL, Fernandez MF, Olea N, Serrano FO . The E-SCREEN assay as a tool to identify estrogens: an update on estrogenic environmental pollutants. Environ Health Perspect 1995; 103 (Suppl 7): 113–122.

Ariazi EA, Brailoiu E, Yerrum S, Shupp HA, Slifker MJ, Cunliffe HE et al. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 inhibits proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 1184–1194.

Yang CZ, Yaniger SI, Jordan VC, Klein DJ, Bittner GD . Most plastic products release estrogenic chemicals: a potential health problem that can be solved. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 989–996.

Yang CZ, Casey W, Stoner MA, Kollessery GJ, Wong AW, Bittner GD . A robotic MCF-7:WS8 cell proliferation assay to detect agonist and antagonist estrogenic activity. Toxicol Sci 2014; 137: 335–349.

Burton K . A study of the conditions and mechanism of the diphenylamine reaction for the colorimetric estimation of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem J 1956; 62: 315–323.

Natarajan N, Shambaugh Gr, Elseth K, Haines G, Radosevich J . Adaptation of the diphenylamine (DPA) assay to a 96-well plate tissue culture format and comparison with the MTT assay. BioTechniques 1994; 17: 166–171.

Hill AV . The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of haemoglobin on its dissociation curves. J Physiol (Lond) 1910; 40: iv–vii.

EPA ACToR Database 2012. Available at http://actor.epa.gov/actor/faces/ACToRHome.jsp;jsessionid=50659B59A0DD4B4E4AE067E41401B3BC (cited 29 March 2012).

Gomez E, Pillon A, Fenet H, Rosain D, Duchesne MJ, Nicolas JC et al. Estrogenic activity of cosmetic components in reporter cell lines: Parabens, UV screens, and musks. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2005; 68: 239–251.

Lemini C, Jaimez R, Avila ME, Franco Y, Larrea F, Lemus AE . In vivo and in vitro estrogen bioactivities of alkyl parabens. Toxicol Ind Health 2003; 19: 69–79.

Draelos ZD . Active agents in common skin care products. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 125: 719–724.

Ogita Y, Takahashi Y, Iwata M, Sasatsu M, Onishi H, Hashimoto S et al. Comparison of physical properties and drug-releasing characteristics of white petrolatums. Pharmazie 2010; 65: 801–804.

Borkowski S . Diaper rash care and management. Pediatr Nurs 2004; 30: 467–470.

Loughran S, Spinou E, Clement WA, Cathcart R, Kubba H, Geddes NK . A prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled trial of petroleum jelly/Vaseline for recurrent paediatric epistaxis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2004; 29: 266–269.

Al Aboud KM, Khachemoune A . Vaseline: a historical perspective. Dermatol Nurs 2009; 21: 143–144.

Meyer E . White Mineral Oil and Petroleum and their Related Products. Chemical Publishing Company: New York. 1968.

Konur Hekimoĝlu S, Kislal Loĝlu S, Hmcal A . In vitro release properties of caffeine II. Effect of type of petrolatum and sodium benzoate. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 1987; 13: 1093–1105.

Kornreich C, Zheng ZS, Xue GZ, Prystowsky JH . A simple method to predict whether topical agents will interfere with phototherapy. Cutis 1996; 57: 113–118.

Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS, Hass BS, Dial SL, Moland CL et al. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol Sci 2000; 54: 138–153.

Buist HE, van Burgsteden JA, Freidig AP, Maas WJ, van de Sandt JJ . New in vitro dermal absorption database and the prediction of dermal absorption under finite conditions for risk assessment purposes. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2010; 57: 200–209.

CIR. Cosmetic Ingedient Review Expert Panel (CIR). Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol 2008; 27 (Suppl 4): 1–82.

Blount BC, Silva MJ, Caudill SP, Needham LL, Pirkle JL, Sampson EJ et al. Levels of seven urinary phthalate metabolites in a human reference population. Environ Health Perspect 2000; 108: 979–982.

Darbre PD . Environmental oestrogens, cosmetics and breast cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 20: 121–143.

Darbre PD, Charles AK . Environmental oestrogens and breast cancer: evidence for combined involvement of dietary, household and cosmetic xenoestrogens. Anticancer Res 2010; 30: 815–827.

Donovan M, Tiwary CM, Axelrod D, Sasco AJ, Jones L, Hajek R et al. Personal care products that contain estrogens or xenoestrogens may increase breast cancer risk. Med Hypotheses 2007; 68: 756–766.

Harvey PW, Darbre P . Endocrine disrupters and human health: could oestrogenic chemicals in body care cosmetics adversely affect breast cancer incidence in women? J Appl Toxicol 2004; 24: 167–176.

Darbre PD, Aljarrah A, Miller WR, Coldham NG, Sauer MJ, Pope GS . Concentrations of parabens in human breast tumours. J Appl Toxicol 2004; 24: 5–13.

Edidin DV, Levitsky LL . Prepubertal gynecomastia associated with estrogen-containing hair cream. Am J Dis Child 1982; 136: 587–588.

DiRaimondo CV, Roach AC, Meador CK . Gynecomastia from exposure to vaginal estrogen cream. New Engl J Med 1980; 302: 1089–1090.

Gottswinter JM, Korth-Schütz S, Ziegler R . Gynecomastia caused by estrogen containing hair lotion. J Endocrinol Invest 1984; 7: 383–386.

Shirai S, Suzuki Y, Yoshinaga J, Shiraishi H, Mizumoto Y . Urinary excretion of parabens in pregnant Japanese women. Reprod Toxicol 2013; 35: 96–101.

Kunisue T, Chen Z, Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Hediger ML, Sun L et al. Urinary concentrations of benzophenone-type UV filters in U.S. women and their association with endometriosis. Environ Sci Technol 2012; 46: 4624–4632.

Boberg J, Taxvig C, Christiansen S, Hass U Update on uptake, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) and endocrine disrupting activity of parabens. Report for Danish Environmental Protection Agency, 2009. Available at http://www.mst.dk/NR/rdonlyres/1D32086E-65A4-4B2C-B74F-6A6C6753DBB7/0/Updateonuptakedistributionmetabolismandexcretion_ADME_.pdf (cited 29 March 2012).

Bennett DH, Wu XM, Teague CH, Lee K, Cassady DL, Ritz B et al. Passive sampling methods to determine household and personal care product use. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012; 22: 148–160.

Wu KM, Dou J, Ghantous H, Chen S, Bigger A, Birnkrant D . Current regulatory perspectives on genotoxicity testing for botanical drug product development in the U.S.A. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2010; 56: 1–3.

Buckley JP, Palmieri RT, Matuszewski JM, Herring AH, Baird DD, Hartmann KE et al. Consumer product exposures associated with urinary phthalate levels in pregnant women. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012; 22: 468–475.

Janjua NR, Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, Wulf HC, Andersson AM . Urinary excretion of phthalates and paraben after repeated whole-body topical application in humans. Int J Androl 2008; 31: 118–130.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Divisions of Intramural Research and the National Toxicology Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by NIH grant 1R43/44 ES014806, 01-03 to C.Z.Y. This article may be the work product of an employee or group of employees of the NIH; however, the statements, opinions or conclusions contained therein do not necessarily represent the statements, opinions or conclusions of NIH or the United States government. We thank Aimee D’Aloisio, Elizabeth Maull, and Kyla Taylor who critically reviewed an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.Z.Y. is employed by and owns stock in CertiChem (CCi). GDB owns stock in and is a consultant CEO of CCi. All authors had freedom to design, conduct, interpret, and publish research uncompromised by any controlling sponsor All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Myers, S., Yang, C., Bittner, G. et al. Estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activity of off-the-shelf hair and skin care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 25, 271–277 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2014.32

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2014.32

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Endocrine disrupting chemical-associated hair product use during pregnancy and gestational age at delivery: a pilot study

Environmental Health (2021)

-

Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2021)

-

Synthesis and Characterization of PVA/Starch Hydrogel Membranes Incorporating Essential Oils Aimed to be Used in Wound Dressing Applications

Journal of Polymers and the Environment (2021)

-

Hair product use, age at menarche and mammographic breast density in multiethnic urban women

Environmental Health (2018)

-

The mutual benefits of research in wild animal species and human-assisted reproduction

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2018)