Abstract

Background

Certain types of hair products are more commonly used by Black women. Studies show hair products contain several endocrine-disrupting chemicals that are associated with adverse health outcomes. As chemical mixtures of endocrine disruptors, hair products may be hormonally active, but this remains unclear.

Objective

To assess the hormonal activity of commonly used Black hair products.

Methods

We identified six commonly used hair products (used by >10% of the population) from the Greater New York Hair Products Study. We used reporter gene assays (RGAs) incorporating natural steroid receptors to evaluate estrogenic, androgenic, progestogenic, and glucocorticoid hormonal bioactivity employing an extraction method using bond elution prior to RGA assessment at dilutions from 50 to 500.

Results

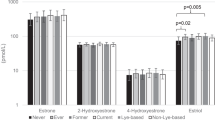

All products displayed hormonal activity, varying in the amount and effect. Three samples showed estrogen agonist properties at levels from 12.5 to 20 ng/g estradiol equivalent concentrations All but one sample showed androgen antagonist properties at levels from 20 to 25 ng/g androgen equivalent concentrations. Four samples showed antagonistic and agonistic properties to progesterone and glucocorticoid.

Significance

Hair products commonly used by Black women showed hormonal activity. Given their frequent use, exposure to hormonally active products could have implications for health outcomes and contribute to reproductive and metabolic health disparities.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gaston SA, James-Todd T, Harmon Q, Taylor KW, Baird D, Jackson CL. Chemical/straightening and other hair product usage during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood among African-American women: potential implications for health. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2020;30:86–96.

James-Todd T, Terry MB, Rich-Edwards J, Deierlein A, Senie R. Childhood hair product use and earlier age at menarche in a racially diverse study population: a pilot study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:461–5.

Kadmiel M, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling in health and disease. Trends Pharm Sci. 2013;34:518–30.

James-Todd T, Senie R, Terry MB. Racial/ethnic differences in hormonally-active hair product use: a plausible risk factor for health disparities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:506–11.

Helm JS, Nishioka M, Brody JG, Rudel RA, Dodson RE. Measurement of endocrine disrupting and asthma-associated chemicals in hair products used by Black women. Environ Res. 2018;165:448–58.

Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong L-Y, Bishop AM, Needham LL. Urinary concentrations of four parabens in the US population: NHANES 2005–2006. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:679–85.

Huang T, Saxena AR, Isganaitis E, James-Todd T. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in the associations of urinary phthalate metabolites with markers of diabetes risk: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2008. Environ Health. 2014;13:1–10.

Deardorff J, Abrams B, Ekwaru JP, Rehkopf DH. Socioeconomic status and age at menarche: an examination of multiple indicators in an ethnically diverse cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:727–33.

Burris HH, Hacker MR. Birth outcome racial disparities: a result of intersecting social and environmental factors. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:360–6.

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41.

Demmer RT, Zuk AM, Rosenbaum M, Desvarieux M. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus among US adolescents: results from the continuous NHANES, 1999–2010. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1106–13.

Johnson TA, Bankhead T. Hair it is: examining the experiences of black women with natural hair. Open J Soc Sci. 2014;02:86–100.

Teteh DK, Montgomery SB, Monice S, Stiel L, Clark PY, Mitchell E. My crown and glory: community, identity, culture, and Black women’s concerns of hair product-related breast cancer risk. Cogent Arts Hum. 2017;4:1345297.

Byrd A, Tharps L. Hair story: untangling the roots of black hair in America. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press; 2001.

Mintel. Natural hair movement drives sales of styling products in US black haircare market 2015. https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/beauty-and-personal-care/natural-hair-movement-drives-sales-of-styling-products-in-us-black-haircare-market.

Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1181–2.

Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013;23:197–206.

Zota AR, Shamasunder B. The environmental injustice of beauty: framing chemical exposures from beauty products as a health disparities concern. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:418.e1–e6.

Myers SL, Yang CZ, Bittner GD, Witt KL, Tice RR, Baird DD. Estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activity of off-the-shelf hair and skin care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2015;25:271–7.

Sakkiah S, Wang T, Zou W, Wang Y, Pan B, Tong W, et al. Endocrine disrupting chemicals mediated through binding androgen receptor are associated with diabetes mellitus. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;15.

Lee HR, Kim TH, Choi KC. Functions and physiological roles of two types of estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, identified by estrogen receptor knockout mouse. Lab Anim Res. 2012;28:71–6.

Davey RA, Grossmann M. Androgen receptor structure, function and biology: from bench to bedside. Clin Biochem Rev. 2016;37:3–15.

Daniel AR, Hagan CR, Lange CA. Progesterone receptor action: defining a role in breast cancer. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2011;6:359–69.

Brown J, Kives S, Akhtar M. Progestagens and anti-progestagens for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD002122.

Markey CM, Michaelson CL, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM. Alkylphenols and bisphenol A as environmental estrogens. Endocrine Disruptors–Part I. 2001:129–53.

Fessenden RJ, Fessenden JS. Trends in organosilicon biological. Adv Organomet Chem. 1980:275:275–99.

Soto AM, Justicia H, Wray JW, Sonnenschein C. p-Nonyl-phenol: an estrogenic xenobiotic released from” modified” polystyrene. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;92:167–73.

Van Meeuwen J, Van Son O, Piersma A, De Jong P, Van Den Berg M. Aromatase inhibiting and combined estrogenic effects of parabens and estrogenic effects of other additives in cosmetics. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:372–82.

Prusakiewicz JJ, Harville HM, Zhang Y, Ackermann C, Voorman RL. Parabens inhibit human skin estrogen sulfotransferase activity: possible link to paraben estrogenic effects. Toxicology 2007;232:248–56.

Chen J, Ahn KC, Gee NA, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Lasley BL. Antiandrogenic properties of parabens and other phenolic containing small molecules in personal care products. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;221:278–84.

Aker AM, Watkins DJ, Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Soldin OP, Del Toro LVA, et al. Phenols and parabens in relation to reproductive and thyroid hormones in pregnant women. Environ Res. 2016;151:30–7.

Klopčič I, Kolšek K, Dolenc MS. Glucocorticoid-like activity of propylparaben, butylparaben, diethylhexyl phthalate and tetramethrin mixtures studied in the MDA-kb2 cell line. Toxicol Lett. 2015;232:376–83.

Suh S, Park MK. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus: an important but overlooked problem. Endocrinol Metab. 2017;32:180–9.

Di Dalmazi G, Pagotto U, Pasquali R, Vicennati V. Glucocorticoids and type 2 diabetes: from physiology to pathology. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012.

Casals-Casas C, Desvergne B. Endocrine disruptors: from endocrine to metabolic disruption. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:135–62.

Grun F, Blumberg B. Perturbed nuclear receptor signaling by environmental obesogens as emerging factors in the obesity crisis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2007;8:161–71.

Wallack G. Rethinking FDA’s regulation of cosmetics. Harv J Legis. 2019;56:311.

Willemsen P, Scippo ML, Kausel G, Figueroa J, Maghuin-Rogister G, Martial JA, et al. Use of reporter cell lines for detection of endocrine-disrupter activity. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:655–63.

Crawford K, Hernandez C. A review of hair care products for black individuals. Cutis. 2014;93:289–93.

Hsieh CJ, Chang YH, Hu A, Chen ML, Sun CW, Situmorang RF, et al. Personal care products use and phthalate exposure levels among pregnant women. Sci Total Environ. 2019;648:135–43.

McDonald JA, Tehranifar P, Flom JD, Terry MB, James-Todd T. Hair product use, age at menarche and mammographic breast density in multiethnic urban women. Environ Health. 2018;17:1.

Orton F, Ermler S, Kugathas S, Rosivatz E, Scholze M, Kortenkamp A. Mixture effects at very low doses with combinations of anti-androgenic pesticides, antioxidants, industrial pollutant and chemicals used in personal care products. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;278:201–8.

Evans RM, Scholze M, Kortenkamp A. Additive mixture effects of estrogenic chemicals in human cell-based assays can be influenced by inclusion of chemicals with differing effect profiles. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43606.

Nadal A, Alonso-Magdalena P, Soriano S, Quesada I, Ropero AB. The pancreatic beta-cell as a target of estrogens and xenoestrogens: Implications for blood glucose homeostasis and diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;304:63–8.

Rosmond R, Chagnon YC, Holm G, Chagnon M, Perusse L, Lindell K, et al. A glucocorticoid receptor gene marker is associated with abdominal obesity, leptin, and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Obes Res. 2000;8:211–8.

Coelingh Bennink HJ. Are all estrogens the same? Maturitas. 2004;47:269–75.

Friedman AJ, Lobel SM, Rein MS, Barbieri RL. Efficacy and safety considerations in women with uterine leiomyomas treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1114–9. 4 Pt 1

Fenton SE. Endocrine-disrupting compounds and mammary gland development: early exposure and later life consequences. Endocrinology. 2006;147:s18–s24.

Samtani R, Sharma N, Garg D. Effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals and epigenetic modifications in ovarian cancer: a review. Reprod Sci. 2018;25:7–18.

Mendelsohn ME. Protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:12–7.

Oakley RH, Cidlowski JA. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1033–44.

Patil AS, Swamy GK, Murtha AP, Heine RP, Zheng X, Grotegut CA. Progesterone metabolites produced by cytochrome P450 3A modulate uterine contractility in a murine model. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:1577–86.

Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Pathogenesis and epidemiology of precocious puberty. Effects of exogenous oestrogens. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:292–302.

Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, Sun P, Narod SA. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313:165–73.

Llanos AAM, Rabkin A, Bandera EV, Zirpoli G, Gonzalez BD, Xing CY, et al. Hair product use and breast cancer risk among African American and White women. Carcinogenesis. 2017;38:883–92.

Eberle CE, Sandler DP, Taylor KW, White AJ. Hair dye and chemical straightener use and breast cancer risk in a large US population of black and white women. Int J Cancer. 2019;147:383–91.

Freedman RR. Menopausal hot flashes: mechanisms, endocrinology, treatment. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;142:115–20.

Poehlman ET, Toth MJ, Gardner AW. Changes in energy balance and body composition at menopause: a controlled longitudinal study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:673–5.

Kassotis CD, Vandenberg LN, Demeneix BA, Porta M, Slama R, Trasande L. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: economic, regulatory, and policy implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:719–30.

Sales growth of leading 20 ethnic hair care brands in the United States in 2014. Consumer Goods & FMCG—cosmetics & personal care. Statista 2014. https://www.statista.com/statistics/315501/sales-growth-top-ethnic-hair-brands-us/.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by the March of Dimes, the American Diabetes Association Minority Postdoctoral Fellowship, and the National Institutes of Health (R01ES026166, T32ES007069, and Black Women’s Health Study R01CA058420). We would like to acknowledge Erika Rodriguez and Victoria Fruh for facilitating parts of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TJ-T jointly conceived of the study, assisted with data interpretation and wrote the manuscript; LC jointly conceived of the study, designed and implemented the hormone assays for testing of hair products, interpreted the data and edited the manuscript; EP assisted with data interpretation and editing of the manuscript; MRQ assisted with editing and preparation of the manuscript; MP conducted the hormone assays for testing of hair products and assisted with data interpretation and editing of the manuscript, YX assisted with data interpretation and editing of the manuscript; BG assisted with data interpretation and writing of the manuscript; SM assisted with data interpretation, writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

James-Todd, T., Connolly, L., Preston, E.V. et al. Hormonal activity in commonly used Black hair care products: evaluating hormone disruption as a plausible contribution to health disparities. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 31, 476–486 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-021-00335-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-021-00335-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differences in personal care product use by race/ethnicity among women in California: implications for chemical exposures

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2023)

-

Methods in Public Health Environmental Justice Research: a Scoping Review from 2018 to 2021

Current Environmental Health Reports (2023)

-

Chemicals of concern in personal care products used by women of color in three communities of California

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2022)

-

Endocrine disrupting chemical-associated hair product use during pregnancy and gestational age at delivery: a pilot study

Environmental Health (2021)