Abstract

Purpose:

Although there is an anticipated need for more genetic counselors, little is known about limitations at the graduate training level. We evaluated opportunities for growth of the genetic counseling (GC) workforce by exploring program directors’ perspectives on increasing number of graduate trainees.

Methods:

Thirty US-based GC program directors (PDs) were recruited through the Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors’ listserv. Online surveys and semistructured phone interviews were used to explore factors impacting the expansion of the GC workforce.

Results:

Twenty-five PDs completed the survey; 18 interviews were conducted. Seventy-three percent said they believe that the workforce is growing too slowly and the number of graduates should increase. Attitudes were mixed regarding whether the job market should be the main factor driving workforce expansion. Thematic analysis of transcripts identified barriers to program expansion in six categories: funding, accreditation requirements, clinical sites, faculty availability, applicant pool, and physical space.

Conclusion:

General consensus among participants indicates the importance of increasing the capacity of the GC workforce pipeline. Addressing funding issues, examining current accreditation requirements, and reevaluating current education models may be effective strategies to expanding GC program size. Future research on increasing the number of GC programs and a needs assessment for GC services are suggested.

Genet Med 18 8, 842–849.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic discoveries are predicted to be among the most significant factors affecting health care over the coming decades.1,2 However, most health-care providers are insufficiently trained to interpret genetic information, often resulting in delayed or inaccurate diagnoses and disease management.3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Health-care providers who specialize in genetics such as medical geneticists and genetic counselors (GCs) fill the knowledge gap and provide education, research, and clinical care.10 Professional groups across multiple fields recommend genetic counseling as part of the standard of care.11,12,13 Over the period 2012–2014, 65% of GCs reported an increase in patient volume.14 Ongoing advancements in genomic medicine (i.e., the integration of individual’s genetic information in diagnostic and therapeutic decision making) will continue to increase the demand for genetic services. Nevertheless, the number of new genetic specialists entering the workforce each year has remained relatively static, and, in fact, the enrollment of medical geneticists has been decreasing.15,16,17

Currently, there are more than 4,000 board-certified GCs.18 Although the GC workforce has increased since the first established graduate program in 1969, the number of annual GC graduates has been relatively static in recent years.19 The average GC program enrolls approximately seven students per year. The 34 GC graduate programs in North America matriculated 264 students in 2014. Most of the more than 800 unique applicants per year are qualified applicants with high grade point averages and Graduate Record Examination scores; however, current programs are unable to accommodate all applicants deemed qualified (Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors, personal communication, 19 August 2015).20 Despite the increasing need for GCs and the growing interest of highly qualified students to enter the profession, understanding of the feasibility and limitations of expanding the GC training programs remains deficient. Therefore, this study seeks to explore GC program directors’ perception of the workforce pipeline and to understand the reasons GC program sizes have remained relatively static in recent years.

Materials and Methods

Program directors (PDs) of the 30 accredited GC programs in the United States in 2011 were invited to participate. Potential participants were solicited via an email invitation through the Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors listserv. A 10- to 15-minute online survey hosted by SurveyMonkey was e-mailed to all eligible participants. The survey collected demographic data and data related to program size, funding, and PDs’ opinions regarding the ability to expand (Supplementary Material S1 online). Semistructured phone interviews were scheduled with participants who completed the survey. Interview times ranged from 30 to 60 minutes and were conducted by one interviewer (V.P.) using an interview guide developed to explore in greater depth PD’s survey answers and to assess barriers (Supplementary Material S2 online). All surveys and interview guides were developed and reviewed by the study team and piloted with two associate/assistant PDs.

Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics in SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY). Phone interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim; each transcript was coded using NVivo9 software (QSR International, Burlington, MA) (V.P.) and reviewed by three research team members (V.P., R.P., and C.W.). Discordances in interpretation were resolved by agreement of at least two of the three members, and the results of descriptive coding were organized into themes.21,22 Survey and interview data were then considered together and discussed with the team to identify unifying ideas and patterns.21,22 This study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (IRB STU00052515).

Results

Demographics

Twenty-five of 30 PDs, representing 86.7% of the total GC students enrolled in the United States in 2011, completed the online survey. Eighteen of the 25 survey respondents agreed to be interviewed. All participants were female, with a range of 1–27 years (median = 7.5) of experience as PDs. The demographics of the interviewed participants were similar to those of the survey respondents ( Table 1 ).

PD opinions on workforce expansion

Participants estimated that their programs can currently accommodate, on average, a maximum of 8.4 students (median = 7 students, range = 4–25 students). Fifteen of the 25 programs surveyed reported an increase in size, five reported a decrease in size, and another five reported no change in the size of their programs in the past 5 years. The reported average size change was approximately 1.75 students and occurred 2–13 years ago (median = 3.5 years ago).

Seventy-three percent of participants felt that programs should actively increase the number of graduates each year and the remaining 27% were undecided. Participants cited three main reasons for believing that the demand for GCs will increase. First, advances in the field of genetics and genomics result in growing technical and specialized knowledge that GCs are well suited to interpret. Second, recent trends wherein GCs are using their skill sets broadly and moving beyond traditional clinical roles create a need for more GCs to fill these expanded roles. Third, because there are many areas in the country still without GC training programs or access to genetic services, the GC field will need to expand to increase access to genetic services. However, there were mixed opinions about job availability for GC graduates and whether the job market should be the main factor driving the expansion of the number of GCs. Participants were split nearly evenly between two schools of thought. Of those who remarked on the job market, 55% (6/11) said the job market should drive program expansion and felt a responsibility to make sure there are enough jobs for graduates before expanding training programs.

“It would be unethical to take a class if I did not feel that there would be jobs available for them.” (Participant 5)

However, 45% (5/11) of participants considered expanding training programs a necessity regardless of job market conditions and felt that increasing the number of graduates will result in increased job opportunities.

“We would have to [grow]. I think the more of us that are out there, the more well-known we become, and so I think it works against us [to not expand].” (Participant 12)

“[Historically], there certainly was no market demand at all because nobody knew what it was. But still people were able to figure out where this service actually fits in very well.” (Participant 3)

Thirteen of 18 participants felt that the GC field is growing too slowly. Despite observing a need for workforce expansion, 5 of 18 participants enrolled less than the maximum program capacity to address emerging issues in clinical site availability. Participants indicated that it would be difficult for programs to increase by more than two students per class in their current circumstances.

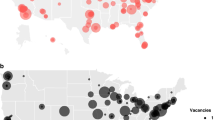

Participants indicated that developing GC graduate programs in underrepresented areas may be the most feasible way to increase the number of graduates each year. However, they also felt that increasing the size of existing programs is the most efficient way to increase the number of graduates each year because the infrastructure and resources already exist for the program. Fifty-seven percent of participants believed that both the size of individual programs and the number of programs should increase ( Figure 1 ).

“There’s not an investment at a national level into GC training programs. We operate kind of in a bubble, without a lot of pressure to expand. And I think it allows us to kind of drudge along and do what we do without really being challenged and saying, here’s a half million dollars or a million dollars to really grow your program. Or here are grants you can apply for, or to challenge us to think about how we can do this. I think you get complacent with the number that you have and it is enough to keep doing this and to keep building relationships in your faculty. [Expansion] doesn’t just happen; it’s a very deliberate process.” (Participant 12)

Barriers to expanding the size of genetic counseling programs

This study identified six main factors to be addressed when expanding GC programs: program funding, accreditation requirements, clinical sites, faculty availability, applicant pool, and physical space ( Table 2 ).

Program funding. Ten of 25 survey participants (40%) provided information about annual expenditures. The reported median annual expenditure was ~$300,000 per program, with a range of $175,000 to $800,000. This results in an approximate expense of $42,000 per student per year (range = $15,000–$75,000/student/year). Seventeen of 25 (68%) participants discussed funding sources. Fifty-three percent of programs listed tuition as the primary source of funding ( Figure 2 ) and felt that the amount of tuition students pay is a concern. Participants also noted the impact of the increasing costs to run a program.

“[Our state] has cut back tremendously the amount of money they are giving to the university and this is coming at a time when we have a lot of GCs in the state that I can easily increase the program because I’ve got the clinical sites for the students now. But now is not the time to go to the department and ask them to pay for the faculty because the answer is going to be no.” (Participant 3)

Although only 6 of 18 interviewees specified funding and budget as barriers for expansion, evaluation of the transcripts indicated that funding is an issue for 14 of 18 interviewees. Participants pointed out that funding is not seen as a barrier by their institutions because increased enrollment is associated with increased tuition revenue for the program.

“Our program is tuition driven. We are a private institution and we do not have outside funding other than financial aid that we can offer to the students. But we do have private funding for the work that the students do…So is it a “limiting” factor? No, I would say not for this program because it’s not a piece we have right now anyway.” (Participant 1)

Despite the fact that there may be no perceived difficulties with institutional funding for some, participants recognized funding as a barrier on a national level. Participants also reflected that the indirect effects and complexities of funding impact many aspects of program operations, and additional funding may positively impact multiple barriers.

“Ultimately, when I look at what limits the number of students in the program…I think it all goes back to the type of funding that we get and even billing and reimbursement issues. If you look at other professions that are able to grow, like the physician assistant programs, they’re able to have a huge number of clinical rotations…because there are a large number of them. So, until we actually have a large number of practicing GCs, there’s always going to be this limitation of how many people we can put out there in training.” (Participant 12)

Accreditation requirements. Ten participants discussed accreditation requirements, and six indicated it could be limiting. Barriers include finding board-certified clinical supervisors at available rotation sites and adhering to traditional training standards that limit novel rotation opportunities at “nontraditional” sites (e.g., specialties outside of prenatal, cancer, and pediatric genetics). Most participants indicated that students’ clinical experiences far exceed the 50 clinical cases required by the accrediting body.

“I could probably increase the program size a bit if I didn’t believe that the variety of rotations that we have in place or the depth of patient involvement that we require our students to have is important. If we are going to meet the absolute minimum standards of 50 cases required by the [accrediting body], then, sure, I could bring more students in and give them fewer cases, but I don’t feel like they would be prepared at that level. And so…if it meant sacrificing either the breadth or the depth of their current patient involvement significantly then that would not be appropriate I don’t think so.” (Participant 10)

Clinical sites and experiences. PDs place significant importance on the variability of clinical cases, supervisors experience levels, and student preferences when assigning clinical rotation sites. The majority (17/18) of PDs considered clinical site availability the main challenge. Limited and competing use of local clinical sites, geographic location and density of clinical sites, and weather/terrains that limit access to roads can have a significant impact on the number of clinical sites that are available to programs. Clinical rotation availability can be further restricted by the type of relationships institutions have with the programs; e.g., facilities from external institutions require affiliation agreements, which are arduous to obtain. Compliance with institutional requirements such as vaccinations and criminal background checks can also be demanding. In addition, occasionally the political climate between institutions dictates the availability of sites.

Supervisor burden is another key consideration in determining the number of available clinical sites. PDs are respectful of supervisors’ commitment to the education of students, which is often provided without monetary or time compensation.

“I think that GCs as a whole right now are pretty overworked and don’t have a lot of time. And some resist [supervising students] because it takes up more time. And so there is definitely interest and good intentions but a lot of times people just can’t or don’t want to take on a student because it’s too much.” (Participant 15)

To encourage supervisors to participate in student education, participants try to build a community of GC experts around the graduate training program, which can be slow and effort-intensive.

Eleven of 18 participants reported that training opportunities may be lacking in some clinical specialties and are unpredictable from year to year. This can be due to institutions restricting the number of students that supervisors are permitted to accept each year, a high turnover rate due to maternity leaves or staff changes, and competition with other trainees, such as medical students, residents, and fellows.

“There have been years when some training sites have been completely unavailable because of either personnel changes or maternity leaves for all or part of the academic year. Some sites’ employees, because of other administrative issues or other demands on supervisors’ time, asked to have you [refrain] from having students there for a period of months or sometimes an entire academic year. And I need to be able to respect their request as that happens.” (Participant 10)

To deal with variability in rotation sites, participants build redundancy into the rotation schedule, try to expand clinical rotation sites in other specialties, use existing rotation sites creatively, and use out-of-state rotations in the summer. Many participants said they feel a lack of control over their clinical rotation sites because multiple factors impact availability.

Program faculty availability and student didactic/research experience. Eleven of 18 participants indicated that faculty availability was a critical factor in expanding program size. Some participants indicated that hiring faculty members can be challenging because program leadership may not have a say in hiring decisions.

“Theoretically, if we accepted another student we would get more tuition. However, it wouldn’t be enough additional income to fund an entire extra salary. In addition, our clinical sites here on campus are currently staffed appropriately and we wouldn’t have need for more counselors on staff clinically.” (Participant 4)

Most program faculty members have part-time or full-time clinical and research responsibilities outside of the program. Mentoring student research projects requires a significant time commitment, and the fact that not every faculty member is available or comfortable advising students can be limiting. The process of building a mentor base is a slow and gradual process.

“When you take on other students it’s not the size of the classroom that’s necessarily problematic, because what’s the difference between having five students versus having eight in a classroom? Not much. It’s really the mentoring. And going from five to eight—it’s a huge difference when students really get a lot of individual attention and mentoring.” (Participant 11)

PD burden was also a concern. Directors balance multiple roles within the program, including administrative responsibilities, teaching, patient care, student supervision, and mentoring research projects. The majority of participants indicated that additional administrative support would be necessary before program expansion. Participants also considered other issues that affect the student’s didactic learning experience, such as classroom dynamics and classroom activities, and indicated that a small student-to-faculty ratio is desirable so that students can have individual attention.

“There is a bit of a trade-off that if you take more students, there will be less opportunity for individual presentations, role plays or whatever it is. The classroom dynamic with 10 or 12 shouldn’t be that different. Obviously if you go up to a much larger number, which we would not, I’m sure things change.” (Participant 5)

Applicant pool and recruitment issues. The majority of participants stated that the quality of applicants is an important factor in the decision to enroll students, but only 18% (3/16) viewed it as a barrier. Although most participants did not believe the applicant pool plays a significant role in the size of their programs currently, they agreed that the current applicant pool will likely be able to support only small expansions and efforts focused on the increasing visibility of the GC profession and that diversity of the applicant pool will be needed for significant expansions.

Physical space. Many participants (7/15) stated that finding additional space for student rooms could be problematic. However, they felt that finding extra classroom space is either not a problem or one that can be easily solved.

Discussion

Expanding the GC workforce is essential to filling an increasing gap between rapid advances in genetic and genomic knowledge and implementation of clinically relevant tools. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 41% growth in the employment of GCs from 2012 to 2022.23 Increasing demands for GCs are also reflected in the expansion into roles in industry, research, labs, and a variety of clinical settings.14 However, at the current rate of graduation, fewer than 2,400 GCs would be added to the workforce in the next 10 years, and only an additional 700 GCs would be added if GC programs continue to expand at the current rate of ~5% (Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors, personal communication, 19 August 2015). Our study indicated that GC PDs recognized the value of increasing the number of GC graduates and felt that the GC workforce is expanding too slowly. However, they were uncertain about whether the job market should dictate workforce expansion and asserted that significant expansion would be very difficult if the GC educational and operational models remain in their current form. Six major factors affecting expansion were identified in this national study: program funding, accreditation requirements, clinical sites, faculty availability, applicant pool, and physical space.

Although the current education model has been highly successful in producing competent GCs, GC graduate programs must be responsive to needs in health care and adapt to changes in the content and delivery of GC education in this competitive service environment. In the changing landscapes of health-services delivery models and an increasingly diverse patient population, medical education is moving from systems-based practice to competency-based education.24,25 Although GCs have been progressive in adapting competency-based training, the current education model also involves intense clinical and research training that requires a tremendous hands-on effort from faculty and has many limitations that prevent a significant increase in class size. Accreditation requirements, especially regarding clinical training, may not always reflect available resources locally or be encouraging to expansion efforts. Our results suggest the need to scrutinize current training practices and reexamine long-held beliefs regarding educational content. Certainly, the quality of GC education should not be sacrificed for the quantity of trained GCs. Although GC education should continue to focus on core skills required for the new generation of GCs, doing so with a larger number of trainees should be considered to meet health-care needs. This may include evaluation of teaching methods that promote deeper levels of critical thinking (such as active learning and team-based learning) and graduate medical education models in other professions. These alternative models may be dynamic enough to maintain quality, accommodate the changing health-care needs, and increase the number of GC trainees.

It is worthwhile to note that similar workforce dilemmas have occurred within other health professions—for example, owing to a shortage of primary-care providers in the 1960s, the federal government injected substantial funding into expanding physician and physician assistant training programs.26,27 The result was a rapid increase in the physician assistant workforce—from fewer than 300 in the early 1970s to more than 74,800 in 2008.28,29 The physician assistant workforce continues to grow at the rate of 17% every year.30,31,32 In 2015, President Obama announced the Precision Medicine Initiative to encourage the integration of precision medicine (disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle) into everyday clinical practice. Despite recognizing the importance of genetics and genomics in medicine, currently there is limited state and federal funding for GC programs compared with other clinical training programs, e.g., physicians and physician assistants.30 Participants in our study noted a lack of funding locally and nationally despite increasing costs of running a program. Increased government funding can have a positive impact on the training of health-care professions and patient access to services;27,28,29 for example, it can relieve student financial burden,33 enhance quality of education through faculty development, and increase clinical training opportunities through institution reimbursement.

This paper highlights only the key barriers of a very complex issue in GC workforce that has both short-term and long-term effects. Some barriers (such as funding and accreditation requirements) do not act independently of others and have downstream effects. For example, the top two barriers that PDs cited as being the most limiting are clinical sites and faculty availability; injection of funding could provide short-term solutions to both problems by increasing the number of GCs to be hired in a program area. However, a growing GC workforce would not be sustainable without sufficient billing and reimbursement for genetic services. Studies have shown that genetic service revenue is closely tied to a GC’s ability to effectively bill for his or her services,34 and physicians are more likely to hire GCs if they can bill independently.35 GCs’ ability to bill could also directly impact their salaries; higher salaries can not only attract more prospective students to the field but also help offset students’ financial burdens of repaying student loans. Thus, efforts to ensure payment for genetic services are critical in the long-term success of GC workforce expansion.

The integration of genetics and genomics into health care means that the need for genetic specialists will continue to increase. Inclusion of genetic counselors can improve access to and elevate the quality of patient care10,36 and reduce the cost of medical expenses.37 Our study identified several opportunities for growth in a time of crucial need for genetic workforce expansion. Two strategies were highlighted because of the systemic impact they would have on multiple barriers: reevaluation of the current GC education model and increased funding for GC education and genetic services. Solutions at the level of the individual institution are critical, but strategies at the national level to reduce barriers, including efforts to sufficiently bill and reimburse for genetic services, are needed to ensure sustainable growth.

Study limitations and future research

One limitation of this study is the inherently subjective nature of qualitative research design. This study represents the opinions of PDs in the United States and thus may have limited generalizability to other programs, regions, or views of the general GC community. Another limitation is that the data were collected 3 years ago. We believe the data are still relevant because GC student enrollment numbers have remained relatively static (e.g., the numbers of matriculates were 237 and 264 in 2011 and 2014, respectively; Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors, personal communication, 19 August 2015), and programs continue to address issues identified in this study (Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors, personal communication, 22 September 2015). Future research in the distribution of genetic services, GCs, and job availability may help elucidate these issues. Furthermore, a needs assessment of GC services grounded in applied social research and surveys of the general medical community are needed to highlight the value of GC services. Collection of outcome data such as employability of GC graduates, documentation of the successful implementation of innovative training strategies, and expert commentary on the future directions of the GC field can promote collaborative development and discussion of strategic initiatives in the future of GC training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Collins F. A genome story: 10th anniversary commentary. Scientific American, guest blog, 25 June 2010. http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2010/06/25/a-genome-story-10th-anniversary-commentary-by-francis-collins/. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. Welcome to the genomic era. N Engl J Med 2003;349:996–998.

Genomic Medicine Centers Meeting IV: Physician Education in Genomics. 2013. Full meeting minutes. http://www.genome.gov/Pages/About/OD/OPG/GMIV/Genomic_Medicine_IV_Minutes.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Baer HJ, Brawarsky P, Murray MF, Haas JS. Familial risk of cancer and knowledge and use of genetic testing. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:717–724.

Baars MJ, Henneman L, Ten Kate LP. Deficiency of knowledge of genetics and genetic tests among general practitioners, gynecologists, and pediatricians: a global problem. Genet Med 2005;7:605–610.

Burke W, Emery J. Genetics education for primary-care providers. Nat Rev Genet 2002;3:561–566.

Emery J, Watson E, Rose P, Andermann A. A systematic review of the literature exploring the role of primary care in genetic services. Fam Pract 1999;16:426–445.

Harvey EK, Fogel CE, Peyrot M, Christensen KD, Terry SF, McInerney JD. Providers’ knowledge of genetics: a survey of 5915 individuals and families with genetic conditions. Genet Med 2007;9:259–267.

Howlett MJ, Avard D, Knoppers BM. Physicians and genetic malpractice. Med Law 2002;21:661–680.

Bernhardt BA, Biesecker BB, Mastromarino CL. Goals, benefits, and outcomes of genetic counseling: client and genetic counselor assessment. Am J Med Genet 2000;94:189–197.

American College of Surgeons. Commission on Cancer, 2012. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. v.1.2.1 Standard 2.3 Risk Assessment and Genetic Counseling. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Accessed 23 March 2015.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2014. NCCN Guidelines for Detection, Prevention, & Risk Reduction. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#detection. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Priori SG, Wilde AA, Horie M, et al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of patients with inherited primary arrhythmia syndromes: document endorsed by HRS, EHRA, and APHRS in May 2013 and by ACCF, AHA, PACES, and AEPC in June 2013. Heart Rhythm 2013;10:1932–1963.

National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2014. 2014 Professional Status Survey: Work Environment. http://nsgc.org/p/do/sd/sid=2478&type=0. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Cooksey JA, Forte G, Benkendorf J, Blitzer MG. The state of the medical geneticist workforce: findings of the 2003 survey of American Board of Medical Genetics certified geneticists. Genet Med 2005;7:439–443.

Cooksey JA, Forte G, Flanagan PA, Benkendorf J, Blitzer MG. The medical genetics workforce: an analysis of clinical geneticist subgroups. Genet Med 2006;8:603–614.

American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Number of Certified Specialists in Genetics. http://www.abmgg.org/pages/resources_certspecial.shtml. Accessed 23 March 2015.

American Board of Genetic Counseling. ABGC History. http://www.abgc.net/About_ABGC/ABGCBylaws.asp. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Office of Biotechnology Activities, National Institutes of Health. Report of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society. Genetics Education and Training, 2011. http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/SACGHS/reports/SACGHS_education_report_2011.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Bennett R. US Department of Health and Human Services: Genetic Counselor Training Program Capacities and Needs. Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society (SACGHS). 23 October 2003. http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Bennett.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Bloomber LD and Volpe M. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Roadmap From Beginning to End. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2008.

Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Sage: Thousand Oak, CA, 2009.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2014–15 Edition, Genetic Counselors. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/genetic-counselors.htm. Accessed 23 March 2015.

Holmboe ES. Realizing the promise of competency-based medical education. Acad Med 2015;90:411–413.

Martinez J, Phillips E, Harris C. Where do we go from here? Moving from systems-based practice process measures to true competency via developmental milestones. Med Educ Online 2014;19:24441.

Davis AK, Reynolds PP, Kahn NB Jr, et al. Title VII and the development and promotion of national initiatives in training primary care clinicians in the United States. Acad Med 2008;83:1021–1029.

Rittenhouse DR, Fryer GE Jr, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Impact of Title VII training programs on community health center staffing and national health service corps participation. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:397–405.

Lipkin M, Zabar SR, Kalet AL, et al. Two decades of title VII support of a primary care residency: process and outcomes. Acad Med 2008;83:1064–1070.

Meyers D, Fryer GE, Krol D, Phillips RL, Green LA, Dovey SM. Title VII funding is associated with more family physicians and more physicians serving the underserved. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:554.

Larson EH, Hart LG. Growth and change in the physician assistant workforce in the United States, 1967-2000. J Allied Health 2007;36:121–130.

American Academy of Physician Assistants, 2012. Past, present, and future: what are projections for the future growth of the profession? And why is it growing so fast? http://www.aapa.org/the_pa_profession/quick_facts/resources/item.aspx?id=3840. Accessed 28 February 2012.

Hooker RS, Cawley JF, Everett CM. Predictive modeling the physician assistant supply: 2010 – 2025. Public Health Reports 2011;126:708–716.

Kuhl A, Reiser C, Eickhoff J, Petty EM. Genetic counseling graduate student debt: impact on program, career and life choices. J Genet Couns 2014;23:824–837.

Leonhard J, Munson P, Flanagan J, et al. Assessment of reimbursement for genetic counseling services in a single institution. Poster Presented at NSGC 33rd Annual Education Conference, New Orleans, LA, 17–20 September 2014.

McRae A. The impact of independent billing by genetic counselors: perspectives from oncologists. Thesis, Northwestern University: Chicago, IL, 2012.

Hannig VL, Cohen MP, Pfotenhauer JP, Williams MD, Morgan TM, Phillips JA 3rd . Expansion of genetic services utilizing a general genetic counseling clinic. J Genet Couns 2014;23:64–71.

Miller CE, Krautscheid P, Baldwin EE, et al. Genetic counselor review of genetic test orders in a reference laboratory reduces unnecessary testing. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:1094–1101.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors for the use of demographic data on GC students. We also thank all the program directors who completed the surveys and phone interviews. This study was supported by the Northwestern University Genetic Counseling Program and conducted with ethical clearance from the Northwestern University IRB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 35 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, V., Yashar, B., Pothast, R. et al. Expanding the genetic counseling workforce: program directors’ views on increasing the size of genetic counseling graduate programs. Genet Med 18, 842–849 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.179

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.179

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Implementing Group Prenatal Counseling for Expanded Noninvasive Screening Options

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2018)

-

Relieving the Bottleneck: An Investigation of Barriers to Expansion of Supervision Networks at Genetic Counseling Training Programs

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2018)

-

Mindfulness Among Genetic Counselors Is Associated with Increased Empathy and Work Engagement and Decreased Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2018)

-

Physician Experiences and Understanding of Genomic Sequencing in Oncology

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2018)

-

Autism genetics: opportunities and challenges for clinical translation

Nature Reviews Genetics (2017)