Abstract

Purpose

To assess the effectiveness and safety of pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) in the management of chronic paediatric uveitis.

Methods

We reviewed records of patients 16 years old or younger who underwent PPV due to persistent uveitis. Data including inflammatory status, ocular findings, visual acuity, dosage and duration of various medical therapies, surgical techniques and complications were collected.

Results

Twenty-eight eyes of 20 patients were included in the study. The diagnoses of uveitis included pars planitis in 15 eyes (54%), idiopathic panuveitis in 8 eyes (29%), and juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated iridocyclitis in five eyes (18%). Six eyes presented with associated retinal vasculitis. The mean age at the time of PPV was 11.2 years. The mean follow-up after surgery was 13.5 months. All 28 eyes had active uveitis with or without medical therapy at the time of PPV. At last follow-up, uveitis control was achieved with or without adjuvant medical therapy in 27 eyes (96%). These included five of the six eyes with persistent retinal vasculitis. Two eyes that had 20-G PPV developed intra-operative retinal tears. Four eyes with pre-operative clear lenses developed cataract within the first 6 months after PPV.

Conclusions

PPV is effective and safe in the management of chronic paediatric uveitis and its complications. It was able to reduce the amount of systemic medications required to control inflammation in this study. Patients with uveitis complicated by retinal vasculitis, however, are more likely to require long-term medical therapy to achieve inflammatory control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Uveitis is an important cause of ocular morbidity in children.1, 2 Early diagnosis and appropriate therapy is critical to prevent sight-threatening complications associated with ocular inflammatory diseases.3, 4 For many years the only available option to treat these patients were systemic and topical corticosteroids, in many cases with prolonged therapy, with the guaranteed adverse effects. The efficacy and relative safety of immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) to control the ocular and possible systemic associations have been shown in the literature.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) has become an increasingly safe procedure and is proving to be an efficacious treatment option for children with stubborn uveitis. Several reports have described the beneficial effect of PPV on the course and complications of uveitis, with a subsequent reduction in the need for IMT following the procedure.12, 13, 14, 15 However, much debate exists as to how best to perform this procedure, including its timing and techniques.

In an effort to answer some of these questions, a comprehensive review of our paediatric patients with treatment-resistant uveitis who had also undergone PPV was conducted, examining multiple factors.

Materials and methods

We conducted a review of the electronic medical records (NextGen, Horsham, PA, USA) at the Massachusetts Eye Research and Surgery Institution (MERSI) of patients 16 years of age or younger who underwent PPV in the setting of persistent uveitis with or without medical therapy from July 2005 to January 2008. Patients with post-operative follow-up shorter than 6 months were excluded from the study. PPV was performed by one of the authors (CSF). The procedure was characterized by the removal of the most possible amount of vitreous with the induction of a posterior hyaloid detachment. The instrumentation used was either 20 or 25 G.

General data included: age, gender, diagnosis, and clinical features of ocular inflammatory disease, including associated systemic conditions. We also included the dose and duration of previous IMT and systemic corticosteroids. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), macular status, lens status, and intraocular pressure (IOP) pre- and post-surgery were also recorded. The BCVA was recorded with the Snellen chart. From the operative notes, we were able to document the techniques employed during the vitrectomies, as well as gauge of instrumentation, surgical findings, and complications.

Ophthalmic examination was performed with the use of biomicroscopy with non-contact lens and indirect ophthalmoscopy. Cataract formation was evaluated with the use of the Lens Opacity Classification System (LOCS III).16 Ocular hypertension was defined as pressure greater than 24 mm Hg and hypotension as pressure less than 6 mm Hg. The ocular inflammation status was defined according to the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group criteria.17 Active inflammation was defined as ⩾1+ anterior chamber cell/flare and/or ⩾1+ vitreous haze. Findings on the retinal angiogram, such as leakage of retinal vessels, were also used in determining the inflammatory status; however, it was considered a separate inflammatory entity from the inflammatory status associated with uveitis.

This observational study adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was control of inflammation, which was defined by the SUN Working Group criteria as ⩽1+ of anterior chamber cell/flare and/or vitreal haze.17 Secondary outcomes included adjuvant medical therapy, control of retinal vasculitis, BCVA, and complications associated with PPV.

Results

Background characteristics

Twenty-eight eyes of 20 patients were included in the study. There were 10 females (50%). The mean age at the time of PPV was 11.2 years (range: 3–16), with 64% of the eyes being operated on when patients were between 11 and 16 years of age. The diagnoses of uveitis included pars planitis in 15 eyes (54%), idiopathic panuveitis in eight eyes (29%), and juvenile idiopathic arthritis associated iridocyclitis in 5 eyes (18%) (Table 1). The mean time between diagnosis and PPV was 19.1 months (range: 2–72). In four patients, this time was not ascertained due to incomplete medical records before being referred to MERSI. The mean follow-up after PPV was 13.5 months (range: 6–29).

Inflammatory status

At the time of PPV, all 28 eyes had active uveitis with or without medical therapy. Six eyes presented with retinal vasculitis in addition to uveitis, as assessed by fluorescein angiogram.

At the last follow-up visit, 27 of the 28 eyes (96%) had no sign of active uveitis following PPV with or without adjuvant medical therapy. These included 5 of the 6 eyes with retinal vasculitis.

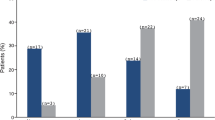

Medical therapy

Before PPV, eight eyes of five patients were on topical corticosteroids. At the last follow-up, six eyes of six patients were on topical corticosteroids. Four eyes had transeptal triamcinolone before PPV, whereas nobody required it after the surgery. Seven patients (nine eyes) were on systemic corticosteroids before PPV, whereas only three patients (four eyes) required them after the surgery. One patient (two eyes) was treated with an oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory pre- and post-operatively and was still on the regimen at the last follow-up. Ten patients (10 eyes) were on IMT (which included methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, chlorambucil, and infliximab) before PPV, whereas only nine eyes of six patients required IMT status post PPV. Five of the six eyes with confirmed retinal vasculitis, which were not on IMT before PPV because of initial parental refusal, required IMT after surgery to achieve resolution of the ocular inflammation. (Table 2).

Best-corrected visual acuity and intraocular pressure

The median pre-operative BCVA was 20/158 (range: 20/20–20/600). Post-operatively, the median post-operative BCVA was recorded at 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months. At 6 months, 28 eyes had a median BCVA of 20/60 (range: 20/20–20/400). At 12 months, 23 eyes had had a median BCVA of 20/56 (range: 20/20–20/400). Finally, at 18 months, 12 eyes had a median BCVA of 20/53 (range: 20/20–20/150). The median pre-operative IOP was 14.2 mm Hg (range: 9–29) whereas the IOP at the last follow-up was 14.4 mm Hg (range: 8–30).

Pre-operative ocular findings

Ten eyes (36%) had cataracts before the surgery. Four eyes (14%) were pseudophakic and one (4%) was aphakic before the surgery. Other common pre-operative pathologic findings were snowballs, snow banking, retinal neovascularization, and retinal vasculitis (Table 3).

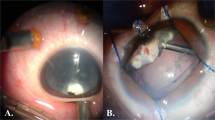

Intra-operative findings and complications

We employed 20-G instruments in 19 (68%) of the study eyes, and only two (7% of total eyes) developed retinal tears, which were treated intra-operatively. One of these eyes developed a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment 1 week after PPV and required scleral buckle. None of the nine (32%) eyes of patients who had 25-G vitrectomy required additional suture to close the sclerotomies, and developed no intra- or post-operative complications. The procedures concurrently performed with PPV were cataract extraction, endolaser, cryotherapy, and intravitreal triamcinolone injection (Table 4). Four of the 13 eyes (14% of total eyes) with clear lenses developed cataracts within the first 6 months after PPV; two of these eyes underwent subsequent cataract extraction. Six of the 10 eyes with pre-existing cataracts required cataract extraction procedure concurrently performed with PPV; four of these received an intraocular lens and two were left aphakic. Whether intraocular lens was implanted depended on the grade of inflammation at the time of procedure.

Discussion

All the study eyes had active uveitis with or without medical therapy at the time of PPV. After PPV, control of uveitis, whether it was associated with retinal vasculitis, was achieved in 27 of the 28 eyes (96%) with or without adjuvant medical therapy. The only patient whose one eye had persistent uveitis noted under the slit lamp in spite of PPV and adjuvant medical therapy was an especially difficult case. He presented with idiopathic panuveitis associated with retinal vasculitis and was treated with chlorambucil before PPV, and at the last follow-up, a decision was made to move along to intravenous therapy with infliximab in an effort to achieve better inflammatory control. Although uveitis was controlled after PPV, five patients whose disease was associated with retinal vasculitis continued to have persistent vessel leakage that was angiographically evident. Therefore, IMT was instituted and inflammation resolved thereafter.

Our study design and results did not permit a direct comparison of effectiveness between PPV and systemic IMT. However, several important observations can be made from our results. First, although IMTs were still required in many patients status post PPV, none of the eyes was under adequate inflammatory control before the procedure. Hence, PPV helped induce inflammatory control in the eyes whose uveitis was resistant to medical treatment. Second, with PPV, the patients in this study were able to reduce the total amount (in terms of the numbers of patients and eyes) of adjuvant anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory therapies necessary to control their uveitis. Topical corticosteroid were continued in five patients and added to one after PPV because the eyes were either pseudophakic or aphakic, and the IOPs were within normal limits without evidence of glaucomatous optic nerve damage. Therefore, the authors, patients, and parents did not sense a strong need to discontinue the drops. It is of note, nevertheless, the number of corticosteroid drops were reduced from 4 × /day to 1–2 × /day in the five patients in whom it was continued after PPV.

The third important observation is that patients with retinal vasculitis in addition to uveitis will more likely require systemic IMT to control the vessel inflammation than those with diseases involving only the uveal tract. A reason for this may be that retinal vasculitis is not a sequelae of the inflammatory mediators released from the uveal tract; rather, it is a separate entity caused by the underlying immunopathology. It is reasonable, however, to assume that some degree of vasculitis is exacerbated by vitreal pathology. Therefore, it is possible that a lower dose and a shorter duration of systemic IMT are needed to treat retinal vasculitis following PPV. To test this notion, a randomized controlled trial, in which patients with both uveitis and retinal vasculitis are divided into PPV and non-PPV arms, will be necessary.

The fourth important observation is that visual acuity was significantly improved with PPV. There are several explanations for this. The first, obviously, is the removal of a diseased vitreous body. The second is the concurrent cataract extraction in some of the eyes. Finally, by lessening inflammation, PPV was able to reduce the degree of macular oedema. The authors are aware that visual acuity is a poor indicator of treatment effectiveness when it comes to uveitis. Nevertheless, PPV was able to improve the anatomical, hence visual, outcomes of many patients in the study.

The authors recognize the obvious limitations to this study. First, it was a retrospective analysis. Second, the number of patients was small; uveitis is relatively uncommon and not every patient or parent is interested in intraocular surgery as its first-line treatment. Therefore, it will take a long time with multicenter participation to recruit patients for prospective, double-masked, and placebo-controlled studies. Third, there is a referral bias in this study because our practice is a tertiary uveitis referral centre. Fourth, there is also a selection bias, as most of the patients in this study who had undergone PPV were ones whose inflammation was poorly controlled on medications. Combining the two biases, it is possible that our outcomes may not hold true for the general paediatric uveitis population. One can only assume, however, that the outcomes of PPV would be more favourable in the less challenging, treatment-resistant cases. Finally, our study is limited by its modest follow-up period after PPV (a mean of 13.5 months).

The reason we have chosen to publish these data despite these limitations is that the results are impressive and we wish to share them with our colleagues, so that not only could PPV be offered to the paediatric population as a therapeutic approach to uveitis, but it would also generate interest in a multicenter study. In addition, we present these data as there remains uncertainty among retinal surgeons regarding the optimal timing and the techniques of PPV in treating uveitis, especially in children. All of the patients had active disease at the time of the surgery, and were not found to have an increased rate of complications when compared with literature reports.18, 19, 20, 21 In terms of age, PPV was successfully performed in a patient as young as 3 years of age in our series. In eyes in which we employed 20-G instruments, only two developed retinal tears, which were treated intra-operatively. None of the eyes, which had 25-G vitrectomy required additional suture to close the sclerotomies, and none developed any intra- or post-operative complication. The rate of cataract and glaucoma development was similar to that published previously.18, 19, 20, 21

In conclusion, our data suggest that PPV is a safe and effective treatment option for chronic paediatric uveitis, with a comparable profile of associated complications as in the adult population. Although it may reduce the overall amount of IMT to which patients are subjected, it is unclear from our results whether PPV is superior or inferior to the medical regimen. Only a randomized controlled trial will be able to elucidate the relationship between the two treatment approaches to chronic uveitis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

De Boer J, Wulffraat N, Rothova A . Visual loss in uveitis of childhood. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87: 879–884.

Rosenberg KD, Feur Wj, Davis JL . Ocular complications of pediatric uveitis. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 2299–2306.

Forrester JV . Uveitis: pathogenesis. Lancet 1991; 338: 1498–1501.

Cunningham Jr ET . Uveitis in children. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2000; 8: 251–261.

Zimmerman TJ . Textbook of Ocular Pharmacology. Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, 1997; 100–101.

Holz FG, Krastel H, Breitbart A, Schwarz-Eywill M, Pezzutto A, Völcker HE . Low-dose methotrexate treatment in noninfectious uveitis resistant to corticosteroids. Ger J Ophthalmol 1992; 1: 142–144.

Dev S, McCallum RM, Jaffe GJ . Methotrexate treatment for sarcoid-associated panuveitis. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 111–118.

Kremer JM . Methotrexate and emerging therapies. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1999; 17: 543–546.

Wallace CA . The use of methotrexate in childhood rheumatoid disease. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41: 381–391.

Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Qazi FA, Nguyen QD, Kempen JH, Dunn JP . Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for inflammatory eye disease. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 1472–1477.

Doycheva D, Deuter C, Stuebiger N, Biester S, Zierhut M . Mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of uveitis in children. Br J Ophthalmolo 2007; 91: 180–184.

Kroll P, Romstock F, Grenzebach UH, Wiegand W . Frühvitrektomie bei endogener juveniler Uveitis media – Eine Langzeitstudie. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 1995; 206: 246–249.

Bacskulin A, Eckardt C . Ergebnisse der pars plana-Vitrektomie. Ophthalmologe 1993; 90: 434–439.

Ulbig M, Kampik A . Pars plana-Vitrektomie bei chronischer Uveitis des Kindes. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 1989; 194: 10–12.

Trittibach P, Koerner F, Sarra G-M, Garweg JG . Vitrectomy for juvenile uveitis: prognostic factors for the long-term functional outcome. Eye 2006; 20: 184–190.

Chylack Jr LT, Wolfe JK, Singer DM, Leske MC, Bullimore MA, Bailey IL et al. The Lens Opacities Classification System III. The Longitudinal Study of Cataract Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111: 831–836.

Standarization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standarization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 509–516.

Diamond JG, Kaplan HJ . Lensectomy and vitrectomy for complicated cataract secondary to uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1978; 96: 1796–1804.

Heiligenhaus A, Bornfeld N, Foerster MF, Wessing A . Long term results of pars plana vitrectomy in the management of complicated uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1994; 78: 549–554.

Eckardt C, Bacskulin A . Vitrectomy in intermediate uveitis. Dev Ophthalmol 1993; 23: 232–238.

Becker M, Davis J . Vitrectomy in the treatment of uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 140: 1096–1105.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giuliari, G., Chang, P., Thakuria, P. et al. Pars plana vitrectomy in the management of paediatric uveitis: the Massachusetts eye research and surgery Institution experience. Eye 24, 7–13 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.294

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.294

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Vitreoretinal surgery in the management of infectious and non-infectious uveitis — a narrative review

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2023)