Download the Nature Podcast 14 February 2024

In this episode:

00:45 Smoking's long-term effects on immunity

It's well-known that smoking is bad for health and it has been linked to several autoimmune disorders, but the mechanisms are not fully understood. Now, researchers have investigated the immune responses of 1,000 people. Whilst some effects disappear after quitting, impacts on the T cell response lingers long after. The team hopes that this evidence could help better understand smoking's association with autoimmune diseases.

Research article: Saint-André et al.

News and Views: Smoking’s lasting effect on the immune system

07:03 Research Highlights

Why explosive fulminating gold produces purple smoke, and a curious act of altruism in a male northern elephant seal.

Research Highlight: Why an ancient gold-based explosive makes purple smoke

Research Highlight: ‘Altruistic’ bull elephant seal lends a helping flipper

09:28 Briefing Chat

An author-based method to track down fake papers, and the new ocean lurking under the surface of one of Saturn's moons.

Nature News: Fake research papers flagged by analysing authorship trends

Nature News: The Solar System has a new ocean — it’s buried in a small Saturn moon

Never miss an episode. Subscribe to the Nature Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast app. An RSS feed for the Nature Podcast is available too.

TRANSCRIPT

Nick Petrić Howe

Welcome back to the Nature Podcast, this week: the long lasting effects of smoking on immunity…

Shamini Bundell

…and the solar system's new ocean. I'm Shamini Bundell.

Nick Petrić Howe

And I'm Nick Petrić Howe.

<music>

Nick Petrić Howe

We all know that smoking is bad for us, but now new research has revealed that it also has long lasting effects on our immune system even years after quitting.

Darragh Duffy

Smoking has a strong impact on the inflammatory response to bacteria, but that's lost as soon as you quit smoking. Whereas the impact on the T cell responses are maintained even many years after you quit smoking.

Nick Petrić Howe

This is Darragh Duffy, one of the authors of the new research in Nature. Now, it’s well known that things like sex, age and genetics shape our immunity — the inflammatory and T cell responses that make up our bodies’ defences. But Darragh and the team were interested in the impacts of other things, things we have a bit more control over. Like whether or not we smoke.

Darragh Duffy

So we recruited 1000 healthy donors. Importantly, they're stratified for both sex and age. So half men, half women, and balanced from the ages of 20, up to 70 years old. And then to study immune response variability, we do whole blood stimulations. So we take one ml of blood and a really standardised approach, and put it in these little syringe based stimulation devices called true culture where we've already pre-incubated with different stimuli. So it can be microbes, it can be viruses, bacteria, fungi, it can be components of those microbes that we know activate specific receptors on immune cells. And then we can look at the immune response, the response to those stimuli in many different ways.

Nick Petrić Howe

So by seeing how people’s immune systems responded differently to various challenges, like bacteria, they could then match it up with other things they knew about those people. Like, did they have any existing infections? What was their BMI? Did they smoke? How long have they smoked for? Or how long ago did they quit?

The team actually found three things that were having a big effect on the immune responses. Whether or not the participants had a dormant cytomegalovirus infection, their BMI and, of course, smoking.

They chose to focus on smoking for a couple of reasons.

Darragh Duffy

One, we were quite struck by how many different associations there were with smoking. The second was the nature of those associations that when we looked a bit closer, they were really interesting. So we saw an effect of active smoking on the innate inflammatory response to bacterial stimulation. But we also saw an effect on the global T cell response. So we saw this dual effect on both the innate and the adaptive response. And then even more intriguing when we broke the smoking effect down into active and past smokers, we saw that the past smokers lost the effect on their inflammatory response, whereas they kept it on the T cell response.

Nick Petrić Howe

These inflammatory, innate responses, are like your body's first line of defence — they react to any kind of challenge. Whereas the adaptive, T cell response is more specific, responding to particular threats.

Now whilst both could affect how people respond to things like bacteria or viruses, Darragh and the team were intrigued as to why there was this effect on the T cell response even years after someone had quit smoking. Violaine Saint-André is another one of the paper’s authors. She had done her PhD in epigenetics — how certain changes, such as the addition or removal of methyl groups, can control the regulation of genes — so she wondered if this was what was causing the long-lasting effects they saw.

Violaine Saint-André

So we see demethylation at some specific metabolism and signal transistor coding genes, with less methylation in active smokers, past smokers compared to non-smokers. And we see, anti-correlation between the number of years people stopped smoking, the total number of cigarettes they smoke, and anti-correlation between the years since they stopped smoking, so this all goes in the same direction.

Nick Petrić Howe

The fewest methyl groups were found on people who smoked for longer or more recently. And this reduction of methylation affected genes that affected T cell function. In other words, more smoking, more of an effect. Exactly what those effects are is something the team still wants to figure out, but they could hold clues to some diseases that seem to be affected by smoking.

Darragh Duffy

Smoking has been implicated in many different pathologies, having higher T cell responses is seen in many autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis associations, in COPD and sarcoidosis, in many different disease settings. So there's still a lot to uncover but this approach is really a kind of tool for discovery that we can identify these associations. And then that gives us a strong piece to go into specific disease studies and test more clear hypotheses.

Nick Petrić Howe

In the future, the team will try and better understand these associations between smoking and immunity. But there may be other things out there affecting our immune systems. Air pollution, much like smoking, means that people inhale harmful things, so Darragh and the team are keen to investigate further.

Darragh Duffy

So one of the genes that showed the strongest methylation effects, the AHRR. So, the AHR is the receptor and AHRR is a repressor of that gene. So AHR basically, is involved in metabolising toxins that you ingest. And that's why it's strongly associated with smoking. But there's definitely evidence that it's involved in processing of other toxins that you can be exposed to in the environment. So there's definitely a strong reason to believe that this mechanism could also be implicated in other environmental exposures. The challenge there is they're harder to study. Because, you know, smoking is self reported. And it's relatively easy to quantify by an individual but environmental exposures, we're not even often aware that we're exposed to them.

Nick Petrić Howe

That was Darragh Duffy, from the Institut Pasteur in Paris. You also heard from Violaine Saint-André, from the same institution. For more on that story, check out the show notes for some links.

Shamini Bundell

Coming up, scientists have found a new ocean on one of Saturn’s moons. Right now though it’s the Research Highlights, with Dan Fox.

<music>

Dan Fox

More than 400 years ago, alchemists discovered a highly explosive substance called fulminating gold. Now, new experiments can explain why its detonation produces purple smoke. Fulminating gold is a mixture made of gold, ammonia and chloride salts that readily explodes into a cloud of purple smoke. Scientists have theorised that particles of gold give this smoke its distinctive colour and now researchers have put this theory to the test. The team used heat to detonate samples of formulating gold and captured the emitted smoke on copper meshes. Analysis using high resolution electron microscopy then revealed what they were looking for — nanometre-sized gold particles. The detected particles had two striking properties: they spanned a broad range of sizes from 5 to more than 300 nanometres and they were spherical. The team says that the explosion of formulating gold could offer a faster way to create such particles. If your interest in formulating gold just exploded, you can read that paper in full in Nanoscale Advances.

<music>

Dan Fox

The dramatic rescue of an elephant seal pup swept out to sea could be the first recorded example of male altruism in the species. Altruism is found throughout the animal world. But the cost of helping others often means that many individuals — and even whole species — don't have much time for charity. Seals, for instance, rarely take part in altruistic acts. But rarely doesn't mean never, as demonstrated by a recent observation of a colony of Northern Elephant Seals in California in the United States when a seal pup less than two weeks old was caught in an undertow at sea. The pup was soon deep enough that it was struggling to keep his head above water. Seemingly in response to the cries of the pup’s mother, an alpha male charged into the sea. Adult males seldom engage with pups. But this bull gently pushed the struggling pup back to shore. You can read more about this observation in Marine Mammal Science.

Nick Petrić Howe

Finally on the show it’s time for the Briefing Chat, where we discuss a couple of articles that have been featured in the Nature Briefing. Shamini, what have you been reading this week?

Shamini Bundell

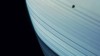

Well, today I am bringing you a whole new ocean, new in the sense that they've just discovered it. Loosely speaking, as you'll see, and new in the fact that it's a relatively new-ish ocean, but this is as far as oceans go. This is a Nature paper and I've been reading a Nature News article about it that I found in the Briefing. And yeah, it's an ocean buried in a moon of Saturn, that they've just kind of decided probably is in fact in there, even though we can't see it.

Nick Petrić Howe

How does one go about finding an ocean that is, as you say, under the surface of a moon?

Shamini Bundell

Well with other moons, it's quite easy because you can see on the surface of the moon so for example, there's like Enceladus which is another like icy moon of Saturn and that has like geysers spewing out of it and they know that there's water under the surface there. But this moon, Mimas or possibly Mimas, depending on how you want to pronounce it. Also, just this icy moon of Saturn, looks and–and this is not my words, “quite boring”. And that is–I'm quoting from the from the News article “they're boring looking” is how it is described, nothing to see on the surface at all. So, they've had to be kind of quite clever. This has been kind of people have been questioning this for a while, whether there could in fact, be water sloshing around inside.

Nick Petrić Howe

And what led them to question whether or not there was water sloshing around inside if the surface is, as you say, “quite boring”.

Shamini Bundell

Sorry, sorry, Mimas sorry, you're not boring. In fact, one of the scientists interviewed does say at the end of this article – “there are no boring moons”. So thank you, planetary scientists for sticking up for moons there. But yes, this particular moon was already sort of noted to be weird in the way that it's orbit wobbled as it went around Saturn. So when Cassini was off exploring Saturn and its moons taking these pictures, researchers were looking at this sort of shape of his orbit then. And basically, because of this wobble, they said, okay, we think it's either got a buried ocean in there, or it's got a weirdly shaped core like it's–the core of the moon it must be shaped like a rugby ball. And so since then, people have been working on those two theories.

Nick Petrić Howe

And what was the key thing then to figure that it was, you know, an ocean rather one of these other alternatives.

Shamini Bundell

It's– it's kind of a little bit of it has just been sort of progress this whole time. But in this particular paper, what they've also done is not just the wobbly orbit, but they've looked at how the rotation around Saturn has changed over time. They've done sort of different simulations of what could be inside it, and its orbit and from this particular paper they reckon there must be an ocean 20 to 30 kilometres below Mimas’ surface and another researcher who wasn't involved in the paper said, this is the best evidence yet for an ocean.

Nick Petrić Howe

And just so I'm sure that I'm imagining this right, this is basically like there's a ball with a bunch of stuff sloshing around in it, which is making its orbit a bit wobbly, I guess. And that's how they've sort of determined this. Is that about right?

Shamini Bundell

Yeah, this is, if you've ever seen pictures of it. This is like the Death Star moon because it's got like this big crater on it that looks a little bit like the sort of indented satellite-dish-type-thing on the Death Star from–from Star Wars. Just to help you picture that. And yes, the idea is that even though on the outside it looks geologically inert – the water is sloshing. That's not just about like making its orbit wobble. The other interesting thing about that, is that when you have the interactions between the ocean water, and the rocky core, that could generate enough chemical energy to sustain living organisms.

Nick Petrić Howe

Ooh.

Shamini Bundell

And so they're not claiming there's aliens on–on Saturn's moon, Mimas. But the point is that if potentially “boring” looking, forgive me, Moon actually has liquid water in, there might be a lot more liquid water around than we thought and the more liquid water there is, the more opportunities there are for extraterrestrial life to exist.

Nick Petrić Howe

Okay, so I've got I've got a good picture of what's going on in my head. But at the start, you said this was newly discovered and also kind of new as well. What did you mean by that? You sort of–

Shamini Bundell

–oh, yeah–

Nick Petrić Howe

–subtly hinted at there.

Shamini Bundell

Okay, okay, so the final point about Mimas’ ocean is that it's, relatively speaking a new, newish ocean. So when I say new, it's formed in the past 25 million years.

Nick Petrić Howe

Oh, brand new.

Shamini Bundell

Well, on Earth, our oceans formed almost 4 billion years ago when the first ocean formed on Earth. So it's 4 billion compared to 25 million. So the blink of a geological eye, so to speak. So it's a young ocean and that is actually one of the reasons why it was hard to spot and why Mimas looks less than thrilling, shall we say, on the outside why the ocean hasn't made itself known and shown on the outside, like on Enceladus say. So actually, that's maybe in the future that's the long-term future that's something that'll change and Mimas might end up looking quite different it might end up looking like Enceladus.

Nick Petrić Howe

Well, if the podcast is still here in about 4 billion years, then we'll be sure to report on how my Mimas’ ocean is looking. But bringing us back down to the present. This week, I've been looking at a story about fake papers, and how looking at the authors on the paper maybe a way to identify their falseness.

Shamini Bundell

Oh, we’ve been talking various things about this haven’t we on the podcast. So, is this like, you could have a whole list of like really cool looking publications on your CV, but they're all actually not genuine journals or not genuine papers or what is it?

Nick Petrić Howe

So this is about fake papers. So these are papers that are produced by what are known as paper mills, which are basically entire industries that are concerned with making fake papers and then selling authorships on those papers.

Shamini Bundell

Right, yeah yeah.

Nick Petrić Howe

And so, we've talked about people buying authorships and stuff before on the Briefing Chat. And, and with this, the main ways people have been trying to identify whether or not papers are false, which is really quite hard to do, is to look at the text and try and figure out from the text if it's fake. So certain clues such as like tortured phrases can give away a paper–

Shamini Bundell

–ah–

Nick Petrić Howe

–as potentially false.

Shamini Bundell

Is that because it was just written by an AI basically?

Nick Petrić Howe

No, AI is actually a kind of a big problem here because AI like things like ChatGPT are a bit more fluent, and they actually produce better sounding text.

Shamini Bundell

Oh.

Nick Petrić Howe

Tortured phrases are where you're basically kind of plagiarising someone, but you're trying to avoid using the same words. So like, rather than saying, I don't know, this won’t be in a paper, but like, “I went to a cake shop,” you might say something like, “I was ensconced in cake”. You know, a sort of unnatural, weird way to say something. And that's been a key clue in the past, but as you alluded to, AI is actually making that problem a little bit more difficult. And so this approach has looked at it a different way. And because these paper mills are trying to sell authorships, it actually means that the authors on them are kind of coming from weird, disparate places. And so they've built a model to identify whether authors coming together looks a bit suspicious, maybe they don't work in the same discipline, or maybe they've never worked on another paper and that sort of stuff. So they're looking at trying to identify whether papers are false through that lens.

Shamini Bundell

Ah, okay, so never mind what the paper is about and how it's written. Is this a plausible sort of group of people who are likely to have got together to write this paper? And if not, that's a clue.

Nick Petrić Howe

Yes, exactly. And so this is a huge problem, these fake papers. So around 2% of papers in 2022 were perhaps from paper mills, which, you know, may not sound like a lot, but if you think millions of papers every year are published. 2% is many, many thousands of papers. So it's quite a lot. And obviously, there's a whole industry here in trying to sell authorships to people and things like that. So this could be a good way to do that, and especially circumvent some of these new challenges, such as AI making the text sound a bit more plausible.

Shamini Bundell

Are fake papers really such a problem, like are people sort of making hiring decisions and publishing decisions based on this without realising they're actually getting duped by complete fabrications?

Nick Petrić Howe

Yeah, so it's a really big problem. And people's careers are often dependent on whether or not they publish, how much they publish, whether they’re first author, whether they’re corresponding author. All these sort of factors are considered when you are going through the sort of scientific career. So it could be a huge problem, you know, you could be giving false promotions to people who have paid for authorship rather than doing the actual work involved. And it's also a massive problem, considering that these are completely fake papers, results in them are meaningless. But people could read that not knowing it and follow certain avenues of research that don't lead anywhere because it was fake to begin with. But it is just really difficult to identify whether or not a paper is fake, because how do you know like, you know, you could challenge people like, where's your data come from, but people don't always reply to requests like that. And then you can go to the journal, the journals may not know, you know, there's a lot of different factors here that makes it really difficult to prove that a paper is actually fictitious. So any other tool to our arsenal is probably a good thing.

Shamini Bundell

What are these researchers going to do with their new tool to sort of potentially identify this?

Nick Petrić Howe

So this was developed by a London-based firm called Digital Science, and they hope that this will be used to help identify researchers that bought their way onto a paper and this code for the model that they've developed that identifies this is available so you can basically start using it straight away and hopefully journals and other organisations that are trying to track down these fake papers can use this in order to identify this and try and really tackle this problem. And because of the business model of these things that are obviously trying to sell authorships to people, that often means that they're going to end up with this disparate, weird group of people. So it potentially is a method that will be harder for the people producing the fake papers to get around, you can maybe make the text better, less tortured phrases and stuff to get around other tools that have been developed to identify this. But if you want to sell to lots of authors from around the world, then it's going to be tricky to get around the fact that they're all from sort of disparate, weird places and probably wouldn't come together necessarily.

Shamini Bundell

That's really interesting. This is– this is a bit of an arms race. So, we're gonna be keeping reporting on sort of both sides, I imagine of the sort of latest ways of finding these fakeries and the latest ways of getting around it. Thank you very much, Nick. And listeners, if you want more about these two stories, you can check out the show notes we're going to put the links there. And then also the link to the Nature Briefing, which is the email newsletter where stories like this get emailed straight to your inbox.

Nick Petrić Howe

That’s all for this week, as always you can keep in touch with us on X, we’re @NaturePodcast. Or you can send an email to podcast@nature.com. I’m Nick Petrić Howe.

Shamini Bundell

And I'm Shamini Bundell. Thanks for listening.

Read the paper: Smoking changes adaptive immunity with persistent effects

Read the paper: Smoking changes adaptive immunity with persistent effects

Smoking: an avoidable health disaster explained

Smoking: an avoidable health disaster explained

The Solar System has a new ocean — it’s buried in a small Saturn moon

The Solar System has a new ocean — it’s buried in a small Saturn moon