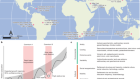

The Biosphere in Montreal, Canada — a geodesic dome designed by architect Buckminster Fuller.Credit: Tibor Bognar/Alamy

Humanity must find viable living spaces beyond Earth in the next 100 years. So urged physicist Stephen Hawking in 2017, in response to human-driven shifts in planetary systems. A year later, entrepreneur Elon Musk met with 60 scientists and engineers in Colorado to discuss Mars colonization. And turning to our home planet, a handful of architects are designing innovative shelters to withstand the impacts of climate change.

Yet artists, scientists, architects and engineers have been dreaming up similar enclosures for centuries. The sealed dome dominates, and for good reason. It offers the greatest volume for the least surface area, and an uninterrupted space free of columns. It is inherently strong, evenly distributing structural stress through tension. And it offers a womb-like sense of safety. Domes have long drawn the futuristically minded, from architect Buckminster Fuller, who in 1960 imagined placing one over Manhattan to regulate atmospheric conditions, to the designers of Arizona research facility Biosphere 2 and radical artist Tomás Saraceno. Domes embody contradictory, yet symbiotic elements: protection, freedom, potential utopias.

Their reliance on sophisticated technologies to engineer specific ecologies and conditions can, however, leave these spaces smacking of technofetishism and anti-democratic tendencies. Some covered synthetic environments have been designed as elitist enclosures, like gated communities. In fact, the history of these ventures is often tied up in imperial ambitions and class perspectives.

Here, we tell the stories of six enclosed spaces. Some are works of the imagination; others are real ventures that pushed technology to its limits. We reconsider all of them in light of the ethical, social and political complexities they embody, in the context of their times.

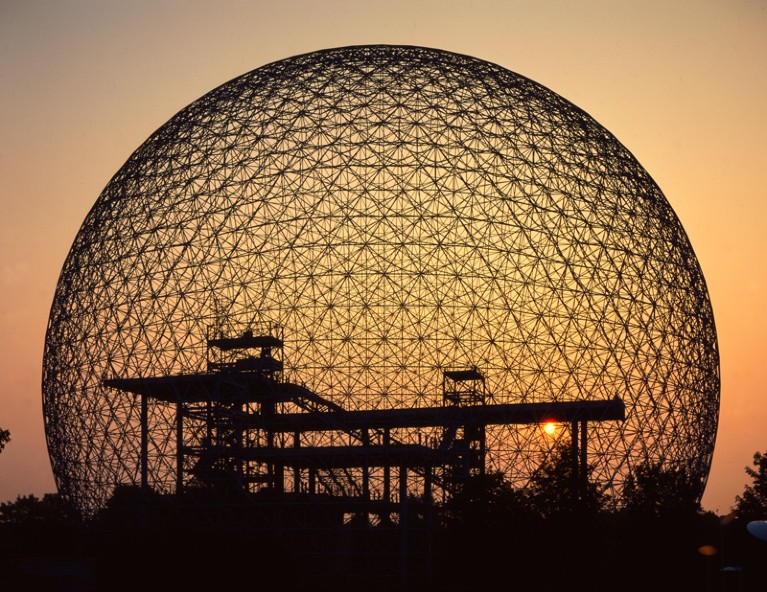

Credit: Universal History Archive/Shutterstock

The curvilinear steel and iron frame of the 1844 Palm House at London’s Kew Gardens supports some 4,200 square metres of glass to maximize light. Created by ironfounder Richard Turner and designer Decimus Burton, its interior climate mimics a tropical rainforest to house specimens collected by plant-hunters such as Francis Masson, who collected its huge South African cycad, Encephalartos altensteinii, in 1773. The steamily realistic atmosphere came courtesy of 12 underground furnaces and a system of pipes and tanks, today replaced by gas-fired heating and atomized humidification. The Palm House represented a wider culture of collecting and containing nature, then fast becoming an object of consumption. It offered a taste of inaccessible, exotic spaces, but also, as Virginia Woolf shows in her 1919 short story ‘Kew Gardens’, a chance for post-Edwardian social classes to mix, sometimes uncomfortably. The glasshouse is now a ‘living laboratory’, supporting a unique collection of plants, many from some of the most threatened environments on Earth.

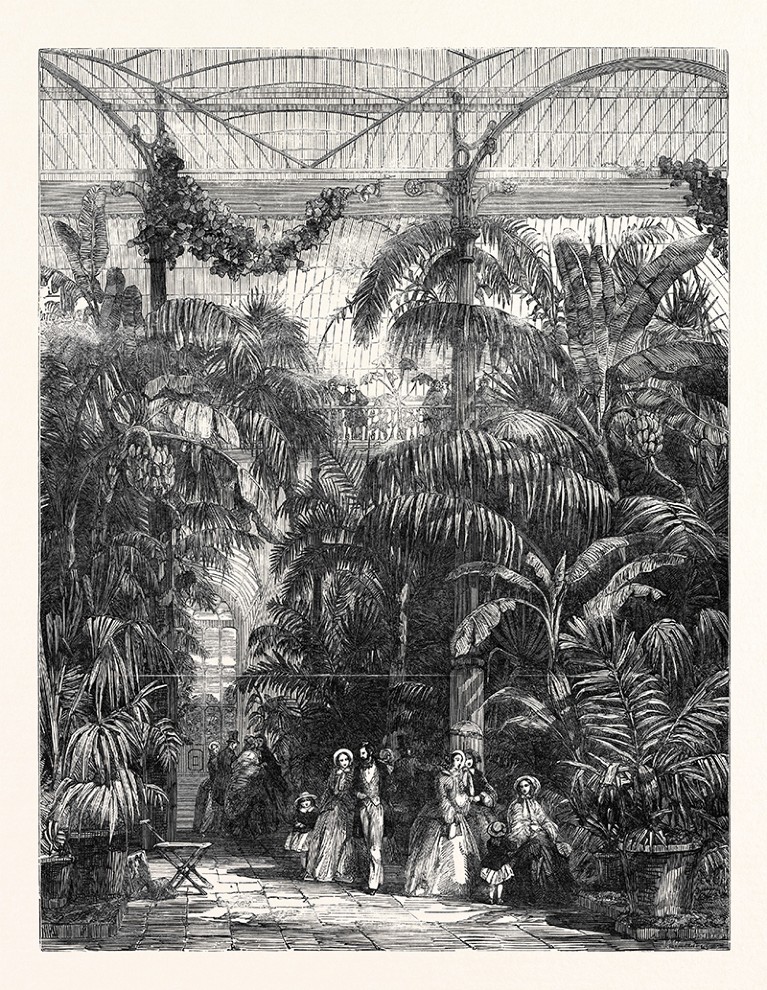

Credit: Frank R. Paul, 'Amazing Stories ' 1942/Mary Evans Picture Library

This fantastical illustration by Frank Paul, Glass City of Europa, graces the cover of a 1942 issue of US science-fiction magazine Amazing Stories. Paul often imagined enormous structures that dwarfed living beings. This one, on a moon of Jupiter, is built from “transparent and opaque plastics” and features giant domesticated invertebrates as transport. In the same magazine, Paul illustrated Cecil White’s 1927 story ‘The Retreat to Mars’, which centres on the remains of ancient Martians, who donned protective proto-spacesuits for an attempt to colonize Central Africa. Paul’s vision is rooted in the science-fiction tradition of male-centred escapism, exploration and colonization — inspired in turn by the likes of modernist Russian writer Alexander Bogdanov, who imagined a socialist utopia on Mars in his 1908 novel Red Star.

Credit: Bettmann/Getty

Sci-fi luminary Arthur C. Clarke thought up the domed city of Diaspar in The City and the Stars (1956). More than a decade later, real-world designers followed suit. Conceived as a home to 40,000 inhabitants in the Arctic Circle, the 1971 Arctic City was envisioned by architects Frei Otto, Kenzo Tange and Ewald Bubner as a dome 2 kilometres in diameter, containing a multilevel urban system (pictured, Otto with a model of the city). Many such utopias, deliberately decoupled from local climates, emerged during the volatile geopolitics of the cold war. The zeitgeist blended concerns for Earth’s environmental future with an obsession with possible new frontiers: oceans and outer space were framed as pristine, awaiting human colonization. This trio of architects, however, never saw their city built. It was deemed too expensive, and there were fears that the sealed-in residents would never acclimatize, and might even develop psychological issues. Much like Fuller’s dome over Manhattan, the City was later described as a “naive utopia”; Otto became highly critical of it later in life.

Credit: Ocean Reef Group/Nemo's Garden 2018

Amid rapid ecological shifts, a sustainable food supply for a growing planetary population is of paramount scientific and social concern. For the Ocean Reef Group, the solution lies on the sea bed, away from more volatile climatic conditions on land. Nemo’s Garden, a project launched in 2012 off the coast of Noli, Italy, aims to create an alternative agricultural system. Using the relatively stable temperature of shallow coastal waters and a predictable supply of solar and artificial light, its six domed greenhouses anchored to the sea floor nurture hydroponic crops such as basil and tomatoes. Currently in the experimental phase, Nemo’s Garden is a world away from the monumental architectural visions explored by many. Like domestic greenhouses, these domes illustrate the possibility of a more do-it-yourself approach to biosphere production.

Credit: Bjarke Ingels Group

With average summer temperatures in excess of 40 °C, the arid, oven-like desert emirate of Dubai is home to extraordinary enclosures, including a 22,500-square-metre skiing centre housed in a gargantuan shopping mall. Energy use for air conditioning is extreme. In fact, in 2010–11, the high demand led to widespread power cuts in the north of the United Arab Emirates. Plans have also been proposed for the first temperature-controlled city. Taking the idea of the domed enclosure even further, in 2017, architect Bjarke Ingels announced plans to build the first simulated Mars City, housing some 175,000 square metres of space under sealed domes on Dubai’s deserts (pictured). A response to the United Arab Emirates’ ambitions to build a Mars colony by 2117, the plans aim to emulate the sustainable, locally sourced constructions created by Indigenous peoples living in extreme climates, such as the Inuit of the Arctic.

Credit: ESA

Space agencies and private companies are meanwhile looking closer to home for possible colonization: the Moon. This computer-generated model of the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Moon Village visualizes a lunar base that combines the capabilities of multiple spacefaring nations, deploying astronauts, robots and technologies such as 3D printing to serve science, industry and tourism. ESA sees such a venture as a “stepping stone” to Mars and beyond. According to the agency, the base could also be used to learn how to better protect Earth from asteroids and space debris. That vision, however, could also be utilized in an entirely different way. Earth and its biosphere need protection from home-grown threats as well as distant ones. Perhaps the view from the Moon will re-orient us towards our home planet and shared environments, and crack open the exclusive futures implicit in the very concept of an enclosing dome. Perhaps, in the words of geographer Denis Cosgrove, such shelters will localize “us within the world rather than beyond it”.

Eco-engineering: Living in a materials world

Eco-engineering: Living in a materials world

Show home for the Red Planet

Show home for the Red Planet

Roving the red planet

Roving the red planet