The Sun: Living with Our Star Science Museum, London. 6 October – 6 May 2019.

Our sense of time, life and almost all energy on Earth stem from something so omnipresent we sometimes forget it is there: the Sun. Now, an exhibition at London’s Science Museum is a reminder of the awe-inspiring power of our star, and its role in shaping everything from health to human cultures.

For scientists, understanding the Sun is essential — not least, for making sense of solar systems beyond our own. Yet many of its features remain mysterious, such as how its atmosphere can become hundreds of times hotter than its surface. Two new missions — NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, launched in August, and the European Space Agency’s 2020 Solar Orbiter — hope to find answers.

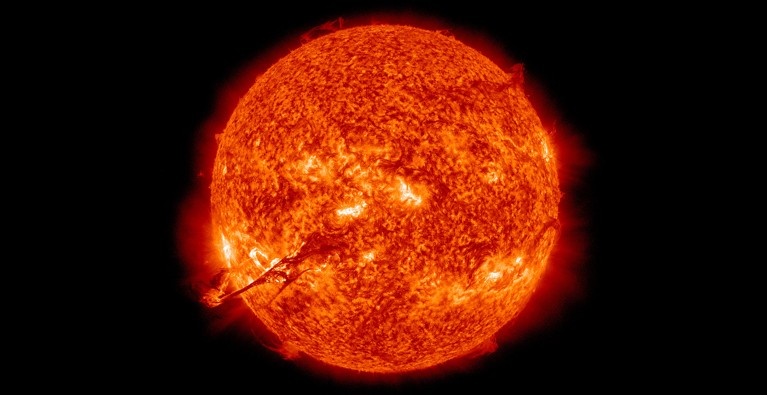

The Sun: Living with Our Star broaches this kind of cutting-edge science by way of a meander through the star’s impact on history and culture, as well as our attempts to harness it. The show is a crescendo, ending in a darkened room with a breathtaking wall-sized video of the Sun’s churning surface, taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory.

An early orrery, a mechanical model of the Solar System built around 1712.Credit: Science Museum Group Coll.

Entering through a psychedelic series of rainbow archways, I’m greeted by an array of exhibits: here an interactive game that turns the visitor into a space-weather forecaster, there a fake beach complete with deckchairs. The Sun might be pretty average among the trillions of stars in the Universe, but a huge collection of artefacts (from ancient artwork to the first sun creams) underlines its all-encompassing influence on Earth. Aptly, light and colour are carefully crafted throughout, not least in the bold prints by Brazilian artist Rafael Alonso that were commissioned for the exhibition.

The Sun’s role in dividing time features heavily — from the focus in ancient Norse mythology on the star’s daily journey across the sky, to the alignment of atomic clocks with astronomical time using leap seconds. The Sun’s double-edged relationship with human health is another theme. Vintage advertisements and posters laud, and warn of, the impact of sunbathing: one US campaign in the 1980s had the slogan “Fry now, pay later”. Sunglasses and solar panels gain dynamism through the stories behind them. A large, grey solar cell was installed by US President Jimmy Carter on the White House roof in 1979; he presciently commented that he hoped the panels would not end up in a museum. (His successor, Ronald Reagan, removed them in 1986.)

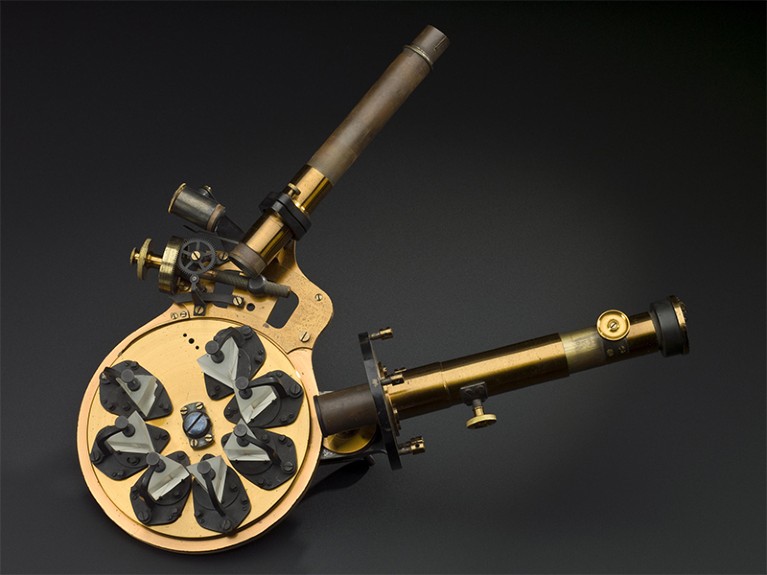

Using this spectroscope, astronomer Norman Lockyer spotted the spectral line of helium in sunlight.Credit: Science Museum Group Coll.

Other gems include a first-edition 1543 copy of Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, and an exquisite wind-up orrery — a mechanical model of the Solar System from 1712. Such models are named after Charles Boyle, Irish earl of Orrery, who commissioned one of the first. Other, more practical instruments bring home how recently we have begun to understand the substance and workings of our star. One is the spectroscope that astronomer (and Nature founder) Norman Lockyer used in 1868 to discover signs of helium in sunlight’s chemical fingerprint.

This is a thoughtfully researched collection. It credits lesser-known figures such as British-American astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, who in 1925 suggested that the Sun was made mostly of hydrogen and helium. US astronomer Henry Norris Russell persuaded her that her conclusions were wrong, and she omitted them from the final version of her thesis — only for Norris Russell to verify them four years later.

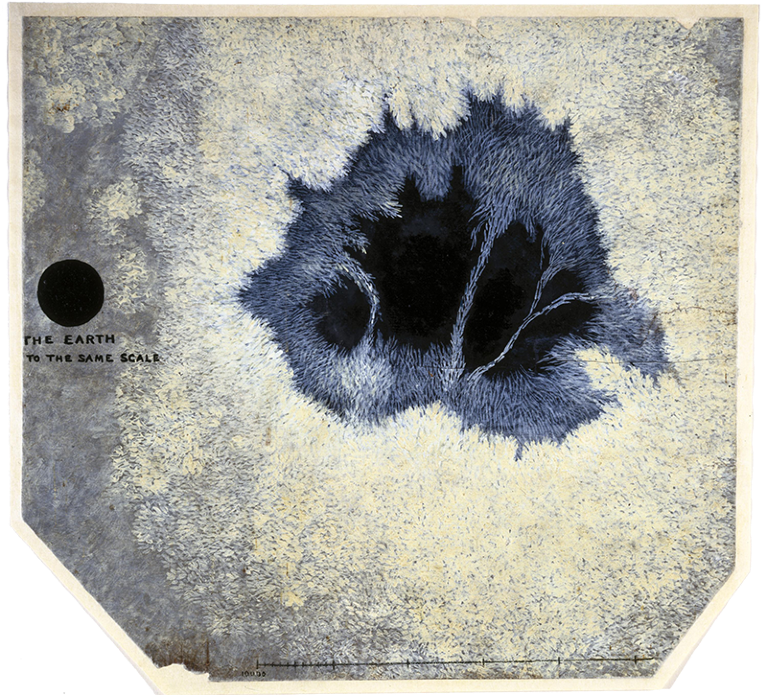

An 1860 painting of a sunspot by engineer James Nasmyth.Credit: Science Museum Group Coll.

The exhibition even crams in space weather, including the potentially catastrophic showers of high-energy particles that career into Earth’s magnetic field. And it touches on the Sun’s own source of energy, nuclear fusion. Yet another section covers solar-inspired art, including a set of incredibly detailed sunspot paintings by the nineteenth-century British engineer James Nasmyth; derived from his own observations, they portray the texture of the Sun’s surface as eerie and almost organic.

In its goal of revitalizing our appreciation for our star, The Sun succeeds. My only quibble is that it brings together so many morsels that some feel like mere tasters. A Babylonian tablet from 700–600 bc, borrowed from the British Museum, is thought to make one of the earliest known references to sunspots or flares. That remarkable find must have its own riveting story, but it is merely touched on.

For me, the exhibition is most successful when bold, deep and emotive. The spectacular, mesmerizing video at the finale conveys the awesome power and violence of the Sun through real data. It can’t fail to change how visitors will feel when they look skywards.

An all-American eclipse

An all-American eclipse

Art of the eclipse

Art of the eclipse

Q&A: Mountain guardian

Q&A: Mountain guardian