Abstract

Background:

Although cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking increase the risk of several cancers and certain components of cigarette smoke and alcohol can penetrate the blood–brain barrier, it remains unclear whether these exposures influence the risk of glioma.

Methods:

We examined the associations between cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and risk of glioma in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study, a prospective study of 477 095 US men and women ages 50–71 years at baseline. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using models with age as the time metric and adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status.

Results:

During a median 10.5 person-years of follow-up, 492 men and 212 women were diagnosed with first primary glioma. Among men, current, heavier smoking was associated with a reduced risk of glioma compared with never smoking, but this was based on only nine cases. No associations were observed between smoking behaviours and glioma risk in women. Greater alcohol consumption was associated with a decreased risk of glioma, particularly among men (>2 drinks per day vs <1 drink per week: HR=0.67, 95% CI=0.51–0.90).

Conclusion:

Smoking and alcohol drinking do not appear to increase the risk of glioma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Apart from a few established risk factors (e.g., exposure to ionising radiation, male sex, non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity) and probable protective factors (e.g., history of allergies), little is known regarding the aetiology of malignant brain tumours, which have a 5-year survival rate of only 34% (Bondy et al, 2008; Dolecek et al, 2012). Cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking are associated with increased risks of several types of cancer, including those of the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, larynx, stomach, colon, and rectum (Bagnardi et al, 2001; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). In addition, components of cigarette smoke, such as N-nitroso compounds, and alcohol can penetrate the blood–brain barrier (Harper, 2007; Il’yasova et al, 2009). However, it remains unclear whether cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking increase the risk of brain cancer.

Results from observational studies on the relationship between cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and risk of glioma, the most common brain malignancy, have been inconsistent, with results differing largely by study design (Mandelzweig et al, 2009; Galeone et al, 2013). Although prospective studies avoid potential biases associated with differential selection and recall between cases and controls and the reliance on proxy respondents, to date, few prospective studies have examined cigarette smoking and/or alcohol intake in relation to glioma risk (Mills et al, 1989; Efird et al, 2004; Silvera et al, 2006; Holick et al, 2007; Benson et al, 2008; Baglietto et al, 2011), and some were relatively small (<100 cases; Mills et al, 1989; Baglietto et al, 2011). Only two prospective studies have investigated risk in relation to beer, wine, and liquor intake with conflicting results; thus, it remains unclear whether consumption of particular types of alcohol influence glioma risk (Efird et al, 2004; Baglietto et al, 2011).

We investigated the relationship between cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and glioma risk in the National Institutes of Health-AARP (formally known as the American Association of Retired Persons, NIH-AARP) Diet and Health Study, a large prospective cohort study with detailed information on cigarette smoking behaviours (smoking status, intensity, and years since quitting) and alcohol drinking (type and level of intake) for more than 450 000 men and women.

Material and methods

Study population

Data collection for the NIH-AARP study was initiated between 1995 and 1996 when questionnaires were mailed to AARP members between the ages of 50 and 71 years who resided in the states of California, Florida, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and North Carolina and the metropolitan areas of Atlanta, Georgia, and Detroit, Michigan (Schatzkin et al, 2001). The self-administered baseline questionnaire ascertained information on demographics, diet, family history of cancer, prior medical conditions, reproductive and hormonal factors, cigarette smoking and alcohol intake, and other lifestyle characteristics (Schatzkin et al, 2001). Cancer outcomes were ascertained through linkage to state cancer registries (Schatzkin et al, 2001). The matching of study participants to cancer registries identified approximately 90% of cancer cases (Michaud et al, 2005). All participants provided informed written consent, and the study was approved by the Special Studies Institutional Review Board of the US National Cancer Institute.

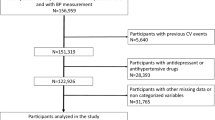

Of the 566 398 individuals who satisfactorily completed the baseline questionnaire, we excluded proxy respondents (n=15 760), participants with self-reported cancer (except for non-melanoma skin cancer; n=51 223) or end-stage renal disease (n=997) at baseline, any cancer cases that were identified only through death records (n=2143), and respondents with missing information on cigarette smoking (n=19 180). Our final study population consisted of 477 095 individuals: 283 979 men and 193 116 women.

Ascertainment of exposure and outcome and follow-up

Smoking was classified according to cigarette smoking status (never, former, current), smoking intensity (1–10, 11–20, 21–30, >30 cigarettes per day), years since quitting (among former cigarette smokers: >0–4, 5–9, 10+ years), and regular use of pipes and cigars for a year or longer (ever vs never). The food frequency questionnaire, an earlier version of the National Cancer Institute’s Diet History Questionnaire, captured portion sizes (beer: <12-ounce can, 1 to 2 12-ounce cans, >2 12-ounce cans; wine: <4 ounces, 4–8 ounces, >8 ounces; liquor and mixed drinks: <1 shot, 1–2 shots, >2 shots) and frequency of consumption (never to ⩾6 times per day) of beer during the summer, beer during the rest of the year, wine and wine coolers, and liquor and mixed drinks over the previous 12 months. Alcohol intake was standardised using the US Department of Agriculture MyPyramid Servings database, with one alcoholic drink corresponding to 12 fluid ounces of beer (12.96 g of ethanol), 5 fluid ounces of wine (13.72 g of ethanol), and 1.5 fluid ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (13.93 g of ethanol). We examined glioma risk according to the frequency of intake (none, <1 drink per week, 1–6 drinks per week, 1–2 drinks per day, >2 drinks per day) for total alcohol, beer, wine, and liquor, separately. We also evaluated the risks of glioma associated with pattern of alcohol intake. Individuals were classified as primarily beer, primarily wine, or primarily liquor drinkers if ⩾75% of their alcohol intake consisted of beer, wine, or liquor, respectively. All other individuals were classified as either mixed drinkers (alcohol drinkers with no apparent alcoholic beverage preference) or nondrinkers.

Cases were defined as individuals diagnosed with first primary malignant glioma (ICD-O-3 site codes C710–-C719 and histology codes 9380–9480). Gliomas were further categorised by histology: glioblastoma (9440–9442), astrocytoma excluding glioblastoma (9383–9384, 9400–9401, 9410–9411, 9420–9421, 9424), and oligodendroglioma including mixed oligoastrocytomas (9450–9451, 9460, 9382). Participants were followed until one of the following occurred: diagnosis of a first primary cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), death, emigration out of the study area, or administrative end date (31 December 2006).

Statistical analysis

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for glioma were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models, adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status with attained age as the underlying time metric. We additionally investigated risk by sex because incidence of glioma is notably higher in men, and it remains unknown whether these sex differences are due to physiological differences or differences in lifestyle-related or environmental exposures. Missing values were modelled using a separate indicator variable. Participants who drank <1 drink per week were the reference group for the models examining total alcohol, beer, wine, and liquor consumption because nondrinkers could include former drinkers who stopped drinking for reasons such as poor health. We did not observe evidence of a deviation from proportional hazards. Tests for linear trend were conducted by modelling categorical variables as continuous and Wald tests were conducted. We also investigated the joint association between total alcohol intake (⩽1 drink per day, >1 drinks per day) and smoking status (never, former, current) on the risk of glioma. Multiplicative interactions were tested by comparing the fit of a model including a cross-product term to a model not including this term using the likelihood ratio test. Where possible, we examined smoking and alcohol in relation to histological subtypes of glioma. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The majority of study participants were former or current smokers, and about half consumed >0 and <1 alcoholic drink per day (Table 1). Current smokers were more likely to be high school graduates and drink primarily beer or liquor relative to never smokers. Compared with nondrinkers, participants who consumed >2 drinks per day were more likely to be male, non-Hispanic white, college graduates, former smokers, and pipe and/or cigar smokers.

During a median 10.5 person-years of follow-up, 492 men and 212 women were diagnosed with glioma. The most common histological subtypes were glioblastoma (542 cases; 77%), astrocytoma (93 cases; 13%), and oligodendroglioma (36 cases; 5%). Compared with never smoking, former (HR=0.90, 95% CI=0.75–1.09) and current (HR=0.67, 95% CI=0.47–0.97) cigarette smoking were associated with a decreased risk of glioma in men only (Table 2). Among men, current, heavier (>20 cigarettes per day) smoking was associated with a reduced risk of glioma compared with never smoking (HR=0.40, 95% CI=0.21–0.79); however, this association was based on only nine exposed cases. Current smoking for ⩽20 cigarettes a day vs never smoking was not associated with risk in men (HR=0.87, 95% CI=0.58–1.32). Men who quit smoking <5 years before baseline had a non-significant reduced risk of glioma (HR=0.73, 95% CI=0.46–1.14) relative to never smokers, but no clear trend with greater number of years since quitting was observed. No clear associations were observed for smoking status, intensity, and time since quitting in women. Cigar and pipe smoking were not clearly associated with glioma risk in men or women. The magnitude of the HRs in the models of smoking and glioma risk did not change appreciably after additional adjustment for total alcohol intake (results not shown).

Overall, we observed a reduced risk of glioma with consumption of >2 drinks per day compared with <1 drink per week (Table 3). Among men, the inverse association appeared to be stronger for beer (HR=0.56, 95% CI=0.33–0.93) compared with wine (HR=0.98, 95% CI=0.53–1.81) or liquor (HR=0.68, 95% CI=0.43–1.09) consumption. The inverse association with beer consumption was less clear in women (⩾1 drink per week vs <1 drink per week: HR=0.66, 95% CI=0.33–1.34), which may reflect the small number of cases (n=9) in women reporting ⩾1 drink per week. Men who were primarily beer (HR=0.77, 95% CI=0.59–1.02) or liquor (HR=0.70, 95% CI=0.51–0.95) drinkers had a reduced risk of glioma compared with alcohol drinkers with no alcoholic beverage preference. Women who were primarily wine (HR=1.50, 95% CI=1.03–2.20) or liquor (HR=1.79, 95% CI=1.15–2.79) drinkers had a significantly increased risk of glioma compared with alcohol drinkers with no alcoholic beverage preference. A possible explanation for the increased risks associated with a preference for wine or liquor is the disproportionately large number of heavier beer drinkers among women in the mixed category (reference group). Adjusting for cigarette smoking status and intensity in the total alcohol, beer, wine, and liquor models or mutually adjusting for the other alcohol types in the beer, wine, and liquor models did not change the HRs appreciably (results not shown).

When we restricted the outcome to glioblastoma, results were similar (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). No associations were observed between ever smoking and risk of astrocytoma for men (HR=0.86, 95% CI=0.51–1.45) or women (HR=1.13, 95% CI=0.53–2.41). HRs per drink per day for astrocytoma in men and women, respectively, were 0.88 (95% CI=0.74–1.06) and 1.02 (95% CI=0.82–1.28). Ever smoking was not significantly associated with risk of oligodendroglioma in men (HR=1.44, 95% CI=0.57–3.65) or women (HR=1.04, 95% CI=0.32–3.45). For each additional alcoholic drink per day, there was a slightly elevated risk of oligodendroglioma among men (HR=1.06, 95% CI=1.02–1.11) but no increased risk among women (HR=1.02, 95% CI=0.71–1.47).

In joint models, current smoking and >1 drink per day was associated with a 63% reduction in risk of glioma in men compared with never smoking and ⩽1 drink per day (HR=0.37, 95% CI=0.17–0.79), and the interaction between smoking status and total alcohol intake appeared to be supra-multiplicative (P-interaction=0.01). The HRs observed for never smoking among men who consumed >1 drink per day and current smoking among men who consumed ⩽1 drink per day were 1.15 (95% CI=0.81–1.64) and 0.90 (95% CI=0.60–1.36), respectively.

Our results did not change materially after excluding the first two years of follow-up time, excluding participants who reported being in poor health at baseline, or after including additional covariates from previous studies of glioma in this cohort: family history of cancer, fruit intake (Dubrow et al, 2010), caffeine consumption (Dubrow et al, 2012), adult height (Moore et al, 2009), and age at menarche (Kabat et al, 2011). We did not observe interactions between sex and smoking status (P-interaction=0.30) or alcohol intake (P-interaction=0.61). Education level did not modify the associations between smoking status (P-interaction=0.93) or alcohol intake (P-interaction=0.52) and the risk of glioma (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

In this large prospective study, heavy, current cigarette smoking was associated with a reduced risk of glioma in men; however, this finding was based on only nine exposed cases. Cigarette smoking was not associated with glioma risk in women. Cigar and pipe smoking were not associated with risk of glioma in men or women. Greater alcohol, particularly beer, consumption was associated with a reduced risk of glioma, most clearly among men. Wine and liquor consumption were not associated with glioma risk in a dose-dependent manner in either men or women.

Because certain components of cigarette smoke (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004) and alcohol (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2010) are established carcinogens, we expected to observe, if anything, positive associations between cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and glioma risk. Of the few prospective studies that separately examined the association between smoking and brain cancer risk in men, the results have generally been null. (McLaughlin et al, 1995; Efird et al, 2004; Holick et al, 2007) Therefore, the inverse association that we observed for current, heavier cigarette smoking and glioma risk in men may be due to chance or residual confounding by other factors, such as socioeconomic status. Current cigarette smoking has been associated with lower education, and the incidence of glioma has been shown to increase with social class (Preston-Martin et al, 2006), particularly among men, and we found similar patterns in the current study. Similar to our results for women, observational studies have generally found no association between cigarette smoking behaviours and risk of glioma in women (Hurley et al, 1996; Blowers et al, 1997; Lee et al, 1997; Zheng et al, 2001; Holick et al, 2007; Benson et al, 2008); however, there were some exceptions, including two prospective studies having observed an increased risk with greater number of cigarettes smoked per day (Efird et al, 2004; Silvera et al, 2006).

The clear inverse association between alcohol drinking and glioma risk in this study, although unexpected, is based on a large number of cases across a wide distribution of intake and concurs with the results from several previous studies on this topic. A meta-analysis of case–control studies, including the largest case–control study published on this topic, reported a significantly reduced risk of glioma for ever vs never drinking in men and women combined (Ruder et al, 2006; Galeone et al, 2013). Similar to results from our study, some (Preston-Martin et al, 1989; Hurley et al, 1996), but not all (Hu et al, 1998), case–control studies support a reduced risk of glioma with beer consumption in men. Results from the few prospective studies on this topic are largely inconsistent, which may reflect small numbers of cases, relatively narrow ranges of alcohol intake, and the inability to separate total alcohol from beer, wine, and liquor (Mills et al, 1989; Efird et al, 2004; Benson et al, 2008; Kim et al, 2010; Baglietto et al, 2011). As in observational studies, confounding by unknown factors is a possibility, and in particular, residual confounding by socioeconomic status is a potential concern in the current study. Beer, wine, and liquor intake have each been associated with socioeconomic indicators (McCann et al, 2003), and glioma incidence appears to increase with social class (Preston-Martin et al, 2006). Although we did not observe dose–response associations for wine or liquor intake or differences in our results for total and specific alcohol types according to education level, we acknowledge lacking information on income, access to health care, and other indicators of socioeconomic status, and residual confounding by socioeconomic status is possible. Although the International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified ethanol as a human carcinogen (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2010), other components of beer may explain its potentially protective effect on glioma (Arranz et al, 2012). Xanthohumol, a polyphenolic compound present in beer, has exhibited anticancer properties, including inducing cell-programmed death in malignant glioma cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Festa et al, 2011; Zajc et al, 2012). These alternative mechanisms may explain why alcohol drinking has also been associated with reduced risks of other malignancies, including renal cell (Allen et al, 2009) and thyroid (Allen et al, 2009; Kitahara et al, 2012) cancers.

To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective cohort study among men and one of the largest among women on cigarette smoking and alcohol intake in relation to risk of glioma. The prospective design ensured that self-reported information on smoking and alcohol intake was not influenced by diagnosis of glioma. In addition, the relatively large number of glioma cases allowed for a precise investigation of risk by sex and across a relatively wide range of total alcohol, beer, wine, and liquor intakes. We were able to examine associations of smoking and alcohol intake in relation to histological sub-types of glioma, which are thought to differ aetiologically (Ohgaki and Kleihues, 2005).

Although a wide range of smoking-related behaviours were ascertained in this study, age at smoking initiation and total number of years smoked were not captured in the baseline questionnaire. In addition, we were unable to account for changes in smoking behaviours during follow-up, which may have attenuated our results. Baseline assessment of alcohol intake was based on consumption over the previous 12 months, so we could not examine associations for patterns in alcohol consumption throughout adulthood. To take into account the possibility that some participants’ alcohol habits may have changed as a result of preclinical disease at baseline, we excluded the first 2 years of follow-up, but our results did not change. There may be residual confounding by other factors that were not ascertained in this study or that were accounted for in the analysis but were measured with error.

Cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking were not associated with an increased risk of glioma in this study. More prospective studies and pooled analyses, particularly ones having a wide range of consumption of alcohol, beer, wine, and liquor, as well as detailed information on drinking patterns throughout adulthood, are needed to provide further insight into the possible inverse association between alcohol drinking and glioma risk.

Change history

07 January 2014

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, Kan SW, Reeves GK, Brown A, Green J (2009) Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 101 (5): 296–305.

Arranz S, Chiva-Blanch G, Valderas-Martinez P, Medina-Remon A, Lamuela-Raventos RM, Estruch R (2012) Wine, beer, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Nutrients 4 (7): 759–781.

Baglietto L, Giles GG, English DR, Karahalios A, Hopper JL, Severi G (2011) Alcohol consumption and risk of glioblastoma; evidence from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Int J Cancer 128 (8): 1929–1934.

Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, Corrao G (2001) A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and cancer risk. Br J Cancer 85 (11): 1700–1705.

Benson VS, Pirie K, Green J, Casabonne D, Beral V (2008) Lifestyle factors and primary glioma and meningioma tumours in the Million Women Study cohort. Br J Cancer 99 (1): 185–190.

Blowers L, Preston-Martin S, Mack WJ (1997) Dietary and other lifestyle factors of women with brain gliomas in Los Angeles County (California, USA). Cancer Causes Control 8 (1): 5–12.

Bondy ML, Scheurer ME, Malmer B, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Davis FG, Il’yasova D, Kruchko C, McCarthy BJ, Rajaraman P, Schwartzbaum JA, Sadetzki S, Schlehofer B, Tihan T, Wiemels JL, Wrensch M, Buffler PA (2008) Brain tumor epidemiology: consensus from the Brain Tumor Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer 113 (Suppl 7): 1953–1968.

Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C (2012) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009. Neuro-Oncology 14 (Suppl 5): v1–v49.

Dubrow R, Darefsky AS, Freedman ND, Hollenbeck AR, Sinha R (2012) Coffee, tea, soda, and caffeine intake in relation to risk of adult glioma in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer Causes Control 23 (5): 757–768.

Dubrow R, Darefsky AS, Park Y, Mayne ST, Moore SC, Kilfoy B, Cross AJ, Sinha R, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Ward MH (2010) Dietary components related to N-nitroso compound formation: a prospective study of adult glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19 (7): 1709–1722.

Efird JT, Friedman GD, Sidney S, Klatsky A, Habel LA, Udaltsova NV, Van den Eeden S, Nelson LM (2004) The risk for malignant primary adult-onset glioma in a large, multiethnic, managed-care cohort: cigarette smoking and other lifestyle behaviors. J Neuro-Oncol 68 (1): 57–69.

Festa M, Capasso A, D’Acunto CW, Masullo M, Rossi AG, Pizza C, Piacente S (2011) Xanthohumol induces apoptosis in human malignant glioblastoma cells by increasing reactive oxygen species and activating MAPK pathways. J Nat Prod 74 (12): 2505–2513.

Galeone C, Malerba S, Rota M, Bagnardi V, Negri E, Scotti L, Bellocco R, Corrao G, Boffetta P, La Vecchia C, Pelucchi C (2013) A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of brain tumours. Ann Oncol 24 (2): 514–523.

Harper C (2007) The neurotoxicity of alcohol. Hum Exp Toxicol 26 (3): 251–257.

Holick CN, Giovannucci EL, Rosner B, Stampfer MJ, Michaud DS (2007) Prospective study of cigarette smoking and adult glioma: dosage, duration, and latency. Neuro-Oncology 9 (3): 326–334.

Hu J, Johnson KC, Mao Y, Guo L, Zhao X, Jia X, Bi D, Huang G, Liu R (1998) Risk factors for glioma in adults: a case-control study in northeast China. Cancer Detect Prev 22 (2): 100–108.

Hurley SF, McNeil JJ, Donnan GA, Forbes A, Salzberg M, Giles GG (1996) Tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption as risk factors for glioma: a case-control study in Melbourne, Australia. J Epidemiol Commun Health 50 (4): 442–446.

Il’yasova D, McCarthy BJ, Erdal S, Shimek J, Goldstein J, Doerge DR, Myers SR, Vineis P, Wishnok JS, Swenberg JA, Bigner DD, Davis FG (2009) Human exposure to selected animal neurocarcinogens: a biomarker-based assessment and implications for brain tumor epidemiology. J Toxicol Environ Health 12 (3): 175–187.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2004) Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking – IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Vol. 83. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2010) Alcohol Consumption and Ethyl Carbamate - IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Vol. 96. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon.

Kabat GC, Park Y, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Rohan TE (2011) Reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use and risk of adult glioma in women in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Int J Cancer 128 (4): 944–950.

Kim MK, Ko MJ, Han JT (2010) Alcohol consumption and mortality from all-cause and cancers among 1.34 million Koreans: the results from the Korea national health insurance corporation’s health examinee cohort in 2000. Cancer Causes Control 21 (12): 2295–2302.

Kitahara CM, Linet MS, Beane Freeman LE, Check DP, Church TR, Park Y, Purdue MP, Schairer C, Berrington de Gonzalez A (2012) Cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and thyroid cancer risk: a pooled analysis of five prospective studies in the United States. Cancer Causes Control 23 (10): 1615–1624.

Lee M, Wrensch M, Miike R (1997) Dietary and tobacco risk factors for adult onset glioma in the San Francisco Bay Area (California, USA). Cancer Causes Control 8 (1): 13–24.

Mandelzweig L, Novikov I, Sadetzki S (2009) Smoking and risk of glioma: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 20 (10): 1927–1938.

McCann SE, Sempos C, Freudenheim JL, Muti P, Russell M, Nochajski TH, Ram M, Hovey K, Trevisan M (2003) Alcoholic beverage preference and characteristics of drinkers and nondrinkers in western New York (United States). Nutr MetabCardiovasc Dis 13 (1): 2–11.

McLaughlin JK, Hrubec Z, Blot WJ, Fraumeni Jr JF (1995) Smoking and cancer mortality among U.S. veterans: a 26-year follow-up. Int J Cancer 60 (2): 190–193.

Michaud D, Midthune D, Hermansen S, Leitzmann M, Harlan LC, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A (2005) Comparison of cancer registry case ascertainment with SEER estimates and self-reporting in a subset of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. J Registry Manag 32 (2): 70–75.

Mills PK, Preston-Martin S, Annegers JF, Beeson WL, Phillips RL, Fraser GE (1989) Risk factors for tumors of the brain and cranial meninges in Seventh-Day Adventists. Neuroepidemiology 8 (5): 266–275.

Moore SC, Rajaraman P, Dubrow R, Darefsky AS, Koebnick C, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A, Leitzmann MF (2009) Height, body mass index, and physical activity in relation to glioma risk. Cancer Res 69 (21): 8349–8355.

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P (2005) Epidemiology and etiology of gliomas. Acta Neuropathologica 109 (1): 93–108.

Preston-Martin S, Mack W, Henderson BE (1989) Risk factors for gliomas and meningiomas in males in Los Angeles County. Cancer Res 49 (21): 6137–6143.

Preston-Martin S, Munir R, Chakrabarti I (2006) Nervous System. In Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention, Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF (eds). 3rd edn., Chapter 62, pp xviii p 1392 Oxford University Press: Oxford; New York.

Ruder AM, Waters MA, Carreon T, Butler MA, Davis-King KE, Calvert GM, Schulte PA, Ward EM, Connally LB, Lu J, Wall D, Zivkovich Z, Heineman EF, Mandel JS, Morton RF, Reding DJ, Rosenman KD (2006) The Upper Midwest Health Study: A case-control study of primary intracranial gliomas in farm and rural residents. J Agric Safety Health 12 (4): 255–274.

Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, Harlan LC, Tangrea J, Hollenbeck AR, Hurwitz PE, Coyle L, Schussler N, Michaud DS, Freedman LS, Brown CC, Midthune D, Kipnis V (2001) Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions: the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 154 (12): 1119–1125.

Silvera SAN, Miller AB, Rohan TE (2006) Cigarette smoking and risk of glioma: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer 118 (7): 1848–1851.

US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA.

Zajc I, Filipic M, Lah TT (2012) Xanthohumol induces different cytotoxicity and apoptotic pathways in malignant and normal astrocytes. Phytother Res 26 (11): 1709–1713.

Zheng TZ, Cantor KP, Zhang YW, Chiu BCH, Lynch CF (2001) Risk of brain glioma not associated with cigarette smoking or use of other tobacco products in Iowa. Cancer Epidem Biomar 10 (4): 413–414.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Braganza, M., Rajaraman, P., Park, Y. et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and risk of glioma in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Br J Cancer 110, 242–248 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.611

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.611

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Modifiable risk factors for glioblastoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Neurosurgical Review (2023)

-

Tobacco smoking associates with NF1 mutations exacerbating survival outcomes in gliomas

Biomarker Research (2022)

-

A combined healthy lifestyle score in relation to glioma: a case-control study

Nutrition Journal (2022)

-

Epidemiology, risk factors, and prognostic factors of gliomas

Clinical and Translational Imaging (2022)

-

Alcohol intake and risk of pituitary adenoma

Cancer Causes & Control (2022)