Abstract

Design

A multicentre case–control study.

Case/control selection

Cases were defined as those diagnosed with primary squamous cell tumours of the UADT between 2002 and 2005. Diagnoses included malignant cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypo-pharynx, larynx or oesophagus. Incident cases were ascertained through weekly monitoring of head and neck cancer clinics in hospital departments and confirmed by pathology department records. Controls were frequency-matched to cases by sex and age (five-year groups). In the UK centres, population controls were randomly selected from the same community medical practice list as the corresponding cases. Specifically, for each case, a total of 10 controls were selected, matched by age and sex. Potential controls were approached in a random order one at a time until one agreed to participate. In all other centres, hospital controls were used. Only controls with a recently diagnosed disease were accepted, and admission diagnoses related to alcohol, tobacco or diet were excluded. Eligible diagnoses included endocrine and metabolic; genito-urinary; skin, subcutaneous tissue and musculoskeletal; gastro-intestinal; circulatory; ear, eye and mastoid; nervous system diseases; trauma and plastic surgery. The proportion of controls within a specific diagnostic group could not exceed 33% of the total in any particular centre.

Data analysis

Personal interviews collected information on demographics, lifetime occupation, history, smoking, alcohol consumption and diet. Socioeconomic status was measured by education, occupational social class and unemployment. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using unconditional logistic regression.

Results

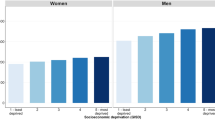

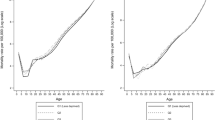

When controlling for age, sex and centre, significantly increased risks for UADT cancer were observed for those with low versus high educational attainment OR = 1.98 (95% CI 1.67, 2.36). Similarly, for occupational socioeconomic indicators – comparing the lowest versus highest International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) quartile for the longest occupation gave OR = 1.60 (1.28, 2.00); and for unemployment OR = 1.64 (1.24, 2.17). Statistical significance remained for low education when adjusting for smoking, alcohol and diet behaviours OR = 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) in the multivariate analysis. Inequalities were observed only among men but not among women and were greater among those in the British Isles and Eastern European countries than in Southern and Central/Northern European countries. Associations were broadly consistent for subsite and source of controls (hospital and community)

Conclusions

Socioeconomic inequalities for UADT cancers are only observed among men and are not totally explained by smoking, alcohol drinking and diet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) are a serious global health concern. Most cases occur in developing countries, whereas the incidence of these cancers is less common in developed countries. Nonetheless, UADT cancers remain a public health problem in Europe due to their poor prognosis and a recent increase in their incidence, particularly in vulnerable populations. The use of tobacco products, heavy alcohol consumption and infection with the human papilloma virus are the main risk factors for these cancers. Although socioeconomic factors have been linked to UADT cancer, this association remains under-researched and poorly understood.

Most studies examining the effects of socioeconomic factors on UADT cancers do not adequately control for known behavioural risk factors. In contrast, the study by Conway and colleagues aimed to assess socioeconomic factors both independently and through their influence on behavioural risk factors. As such, the authors controlled for smoking, alcohol drinking and diet, which could confound any relationship between UADT cancer and social factors.

This multicentre case-control study was conducted in 14 centres in 10 European countries and enrolled 2198 cases of UADT cancer and 2141 controls. The selection criteria of cases and controls were rigorous and data were collected by trained interviewers conducting face-to-face interviews using a highly structured questionnaire. Measures of socioeconomic status (SES) were education and occupational social class. Education variables captured level of educational attainment and number of years of full-time education. Furthermore, the authors took into account variations in educational systems across countries, and these variations were recorded and standardised. For the purpose of the analysis, educational levels were grouped into three broad categories: primary (no education/primary), secondary and tertiary (further/technical/university). As for occupational social variables, they included the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (ISEI) and the Registrar General's Social Class (RGSC).

The distribution of UADT cancer subsites for cases was oral/oropharyngeal (51%), hypopharynx/larynx (39%) and oesophageal (10%). Among cases, there were four times more men than women. Analyses were stratified by sex and four defined geographical country groupings: United Kingdom/Ireland (British Isles), France/Germany/Norway (Central/Northern Europe), Greece/Italy/Spain (Southern Europe) and Croatia/Czech Republic (Eastern Europe).

The study showed that UADT cancer risk increased with low occupational social class and the experience of lifetime unemployment. However, when adjusted for smoking, alcohol and diet, the ORs decreased and these associations became statistically insignificant.

Moreover, UADT cancer risk increased with lower levels of educational attainment. Those with the lowest levels (no formal education) had an almost three-fold increased risk when compared with those in the highest level (university education). When adjusted for smoking, alcohol and diet, the risk associated with the lowest educational attainment level remained significant but showed some decrease (OR = 1.68; 95% CI: 1.08, 2.61) when compared to the highest educational level. Including all three behaviours together accounted for 67% of the increased risk for those with low education.

There was also a statistically significant interaction between education and sex, and the authors conducted stratified analyses by sex to control for this. Significant increased risks associated with low educational attainment were only observed in men in grouped country analyses. Moreover, odds ratios were considerably lower in Southern European and Central/Northern European countries than in the British Isles and Eastern European countries. A similar pattern was observed in women (P>0.05). This lack of statistical significance could be attributed to the relatively small sample size of women compared to men. The study exhibited numerous strengths including a large sample size, strict inclusion criteria and the use of multiple socioeconomic measures to assess SES. However, it is important to note that interview case–control studies have limitations imposed by study design. Recall bias regarding exposure to risk factors, especially among cases, is an inherent limitation in these studies. In addition, it is often difficult to select cases and controls who are representative of their respective populations.

The overall findings of this study are similar to those of other studies from North America1, 2 and Europe.3, 4, 5 These studies reported an increased risk of head and neck cancers in individuals with lower SES, as determined by a range of educational, income and occupational measures. Furthermore, the majority of recent studies support the argument that individuals with more disadvantaged SES have statistically-significant higher rates of head and neck cancers, even after controlling for potential behavioural confounders such as smoking and alcohol consumption.1, 2, 3 In addition, there is evidence to indicate that higher SES, as measured by SES index, education and income, is associated with a decreased risk of oral premalignant lesions.6

Higher SES may be associated with better access to medical care and favourable health-related behaviours, living environment or psychosocial factors. Nevertheless, the association between low SES and UADT cancer risk is yet to be fully explained. New scientific findings show that low SES may be associated with accelerated biological aging. Data from the nationally representative U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III cohort were used to examine the hypothesis that socioeconomic status is consistently and negatively associated with levels of biological risk, as measured by nine biological parameters known to predict health risks. The study revealed that education and income effects were each independently and negatively associated with cumulative biological risks, and that these effects remained significant independent of age, gender, ethnicity and lifestyle factors such as smoking and physical activity.7 Moreover, Steptoe and colleagues found that low SES, defined in terms of education rather than current socioeconomic circumstances, is associated with faster aging. In order to demonstrate this, they measured the length of telomeres, sections of DNA that cap the ends of chromosomes to protect them from damage. Results showed that shorter telomeres, which are thought to be an indicator of faster ageing, were associated with lower education. This association remained statistically significant after adjusting for biological and behavioural factors such as age, gender, blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoking, body mass index and physical activity. In contrast, neither household income nor employment grade was related to telomere length.8

In conclusion, the Conway et al. study provided evidence that socioeconomic effects on the risk of UADT cancer are not fully explained by the traditional behavioural factors of smoking, alcohol consumption and diet. Furthermore, the study showed that the association between the lowest levels of education and UADT cancer risk remained significant, while controlling for behavioural factors, and was consistent across UADT cancer subsites. This residual risk suggests that education may be a very powerful socioeconomic factor and a more precise determinant of a person's long-term health than their current income and social status. The impact of education may be attributed to its influence on risky behaviours, lifestyle choices, occupation, income and access to healthcare. However, recent evidence suggests that education may impact cancer risk through pathways other than risky behaviours. Low educational attainment may increase allostatic load, the physiological consequences of chronic exposure to the neural or neuroendocrine stress response,9,10 resulting in telomere shortening. Conversely, high educational attainment may promote cognitive skills that lead to the reduction of biological stresses.

Finally, the link between UADT cancer risk and low education warrants further investigation of the biological processes associated with educational attainment. Moreover, health policies aimed at reducing cancer risks in Europe and elsewhere must promote an integrated approach that incorporates measures to reduce lifestyle risk factors as well as causes of socioeconomic disparities and educational inequalities.

References

Johnson S, McDonald JT, Corsten MJ . Socioeconomic factors in head and neck cancer. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 37: 597–601

Johnson S, McDonald JT, Corsten M, Rourke R . Socio-economic status and head and neck cancer incidence in Canada: a case-control study. Oral Oncol 2010; 46: 200–203

Conway DI, Petticrew M, Malborough H, Berthiller J, Hasibe M, Macpherson LM . Socioeconomic inequalities and oral cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer 2008; 122: 2811–2819

Anderson ZJ, Lassen CF, Clemmensen IH . Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 1950–1961.

Conway DI, McMahon AD, Smith K, et al. Components of socioeconomic risk associated with head and neck cancer: a population-based case-control study in Scotland. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 48: 11–17.

Hashibe M, Jacob BJ, Thomas G, et al. Socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors and oral premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol 2003; 39: 664–671

Seeman T, Merkin SS, Crimmins E, Koretz B, Charette S, Karlamangla A . Education, income and enthic differences in cumulative biological risk profiles in a national sample of US adults: NHANES III (1988–1994). Soc Sci Med 2008; 66: 72–87.

Steptoe A, Hamer M, Butcher L, et al. Educational attainment but not measures of current socioeconomic circumstances are associated with leukocyte telomere length in healthy older men and women. Brain Behav Immun. Epub 2011 Apr 23; doi: 10.1016/jbbi.2011.04.010.

McEwen BS . Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 171–179.

McEwen BS, Stellar E . Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153: 2093–3101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr.DI Conway, Dental School, Faculty of Medicine, University of Glasgow, 378 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow G2 3JZ, UK. E-mail: d.conway@dental.gla.ac.uk

Conway DI, McKinney PA, McMahon AD, et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancer in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46: 588–598. Epub 2009 Oct 24.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Dakkak, I., Khadra, M. Socio-economic status and upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Evid Based Dent 12, 87–88 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400815

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400815