Abstract

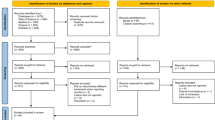

Data sources

Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, the Wiley online database, four journals (Journal of Endodontics, International Endodontic Journal, Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral Pathology Oral Radiology and Endodontology and Endodontics and Dental Traumatology) and the references of identified articles were searched manually. There was no language restriction.

Study selection

Clinical studies that provided sample size, and where success was based on radiographic and/or clinical criteria that evaluated quality of root filling, the quality of coronal restoration and periapical status at least one year after root canal treatment that provided an overall success rate or sufficient data to allow it to be calculated from the raw data were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were collected based on predetermined criteria. Percentages of teeth without apical periodontitis were recorded for each category: adequate root canal treatment (AE); inadequate root canal treatment (IE); adequate restoration (AR); and inadequate restoration (IR). Data were analysed using meta-analysis for odds ratios (ORs).

Results

Nine article were included . After adjusting for significant covariates to reduce heterogeneity, the results were combined to obtain pooled estimates of the common OR for the comparison of

AR/AE versus AR/IE:-

AR/AE versus AR/IE (OR = 2.734; 95%CI, 2.61–2.88; P < .001)

AR/AE versus IR/AE (OR = 2.808; 95% CI, 2.64–2.97; P < .001).

Conclusions

On the basis of the current best available evidence, the odds for healing of apical periodontitis increase with both adequate root canal treatment and adequate restorative treatment. Although poorer clinical outcomes may be expected with adequate root filling-inadequate coronal restoration and inadequate root filling-adequate coronal restoration, there is no significant difference in the odds of healing between these two combinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

The concept of the impact of the quality of coronal restoration and thus the coronal leakage on the outcome of root canal treatment has been characterised many years ago.1 Several researchers have examined this phenomenon trying to identify the sources of possible re-contamination and emphasised the role of the clinician in preventing coronal leakage following root canal treatment.2

Nowadays, it has been proven that inflammatory peri-radicular diseases develop when contamination occurs by microorganisms and/or their by-products.3,4 Therefore, the major goals of root canal treatment are to 1) reduce if not to eradicate intra-radicular bacteria and digest all soft tissues within the root canal system, 2) obturate the cleaned and shaped system in an attempt to leave no space for new bacterial invasion and growth or prevent residual bacteria from obtaining nourishment and hence re-emerging within the root canal space.5

In spite of strict adherence to these principles with current state of the art new technologies in modern endodontic practice, we are still faced with cases where well-filled root canals are re-contaminated and present with signs/symptoms of disease or – ironically – poorly executed root canal treatment with signs of healing. Therefore the current systematic review and meta-analysis by Gillen et al. is more than welcome to bridge some of the gap between the two extremes. In the present study, the authors carefully identify potential design issues and limitations to the work and ended up with nine studies performed between 1995 and 2009. The study did provide an important conclusion: the odds for ending up with 'healing' results of non-surgical root canal treatment increases with both adequate root canal treatment and coronal restoration, and less probability of healing if any of the two procedures fail to be adequate.

These results have strong therapeutic and research implications. First, adequately root filled teeth with adequate post-endodontic restoration produced better treatment outcomes. This by itself might be enough to motivate dental practitioners to consider immediate permanent restoration instead of provisional ones as this step is considered among the elements of the equation of success. The fear of ending up with non-healing periapical lesions can be dealt with as having plan B for managing refractory cases which is endodontic micro-surgery.6 Second, consistent, predictable results in endodontics can only be achieved by consistent approach of treatment.

Practice point

-

Restoration of an endodontically treated tooth should commence as soon as possible after root canal treatment and better yet, restorative treatment plans should be finalised even before the start of the endodontic phase of the treatment plan.

-

Thoroughness of the root canal cleaning, shaping and obturation cannot be substituted by adequate coronal restoration.

References

Bergenholtz G, Cox CF, Loesche WJ, Syed SA . Bacterial leakage around dental restorations: its effects on the dental pulp. J Oral Pathol 1982; 11: 439–450.

Sunde PT, Olsen I, Debelian GJ, Tronstad L . Microbiota of periapical lesions refractory to endodontic therapy. J Endod 2002; 28: 304–310.

Kakehashi S, Stanley HR, Fitzgerald RJ . The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg, Oral Med Oral Pathol 1965; 20: 340–349.

Möller AJ, Fabricius L, Dahlén G, Öhman AE, Heyden G . Influence on periapical tissues of indigenous oral bacteria and necrotic pulp tissue in monkeys. Scand J Dent Res 1981; 89: 475–484.

Sjogren U, Hagglund B, Sundqvist G, Wing K . Factors affecting the long-term results of endodontic treatment. J Endod 1990; 16: 498–504.

Kim SG, Solomon C . Cost-effectiveness of endodontic molar retreatment compared with fixed partial dentures and single-tooth implant alternatives. J Endod 2011; 37: 321–325.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Franklin R Tay, Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, Georgia Health Sciences University, Augusta, GA 30912-1129, USA. E-mail: ftay@georgiahealth.edu

Gillen BM, Looney SW, Gu LS, et al. Impact of the quality of coronal restoration versus the quality of root canal fillings on success of root canal treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2011; 37: 895–902. Epub 2011 May 24.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balto, K. Root-filled teeth with adequate restorations and root canal treatment have better treatment outcomes. Evid Based Dent 12, 72–73 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400806

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400806

This article is cited by

-

Impact of endodontic post material on longitudinal changes in interproximal bone level: a randomized controlled pilot trial

Clinical Oral Investigations (2019)