Abstract

Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors typically occur in familial form associated with KIT receptor tyrosine kinase or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFRA) germline mutations, but may also develop in the setting of type 1 neurofibromatosis. The molecular abnormalities of gastrointestinal stromal tumors arising in neurofibromatosis have not been extensively studied. We identified three patients with type 1 neuro-fibromatosis and multiple small intestinal stromal tumors. Immunostains for CD117, CD34, desmin, actins, S-100 protein, and keratins were performed on all of the tumors. DNA was extracted from representative paraffin blocks from separate tumor nodules in each case and subjected to a nested polymerase chain reaction, using primers for KIT exons 9, 11, 13, and 17 and PDGFRA exons 12 and 18, followed by direct sequencing. The mean patient age was 56 years (range: 37–86 years, male/female ratio: 2/1). One patient had three tumors, one had five, and one had greater than 10 tumor nodules, all of which demonstrated histologic features characteristic of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and stained strongly for CD117 and CD34. One patient died of disease at 35 months, one was disease free at 12 months and one was lost to follow-up. DNA extracts from 10 gastrointestinal stromal tumors (three from each of two patients and four from one patient) were subjected to polymerase chain reactions and assessed for mutations. All of the tumors were wild type for KIT exons 9, 13, and 17 and PDGFRA exons 12 and 18. Three tumors from one patient had identical point mutations in KIT exon 11, whereas the other tumors were wild type at this locus. We conclude that, although most patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis and gastrointestinal stromal tumors do not have KIT or PDGFRA mutations, KIT germline mutations might be implicated in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in some patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are mesenchymal tumors that arise throughout the gastrointestinal tract and, rarely, in the mesentery or retroperitoneum. They are characterized by strong immunohistochemical staining for CD117 and most contain activating mutations in the KIT receptor tyrosine kinase, particularly at exons 9, 11, 13, and 17.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Approximately one-third of tumors that are wild type at the KIT gene harbor mutations in the juxtamembrane and tyrosine kinase domains of a related tyrosine kinase receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFRA).11, 12, 13 In most cases, GISTs are sporadic in nature, however, they may occur as multiple lesions in familial forms associated with KIT or PDGFRA germline mutations.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 In these situations, GISTs arise in a background of interstitial cell of Cajal hyperplasia and may be associated with systemic manifestations including skin hyperpigmentation and mast cell disorders.14, 15, 20, 21 An association between the development of multiple GISTs and type 1 neurofibromatosis has also been established, however, the molecular abnormalities of GISTs arising in this setting have not been elucidated and studies assessing their molecular features are limited.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate a series of multiple GISTs in patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis, in an effort to identify any distinctive morphologic features of these tumors and molecular abnormalities in the KIT and PDGFRA genes.

Materials and methods

Study Group

The study group consisted of three patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis and multiple GISTs who were prospectively identified from the UMass Memorial Health Care Department of Pathology (two cases) and the Department of Pathology of the Massachusetts General Hospital (one case), during the time period of 1999–2003, inclusively. The diagnostic criteria for type 1 neurofibromatosis were derived from the National Institutes of Health consensus statement and included at least two of the following features: six or more café au lait spots greater than 15 mm in diameter in a postpubertal patient, two or more neurofibromas of any type or at least one plexiform neurofibroma, freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions, and the presence of an optic glioma, two or more hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), bone lesions such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of the cortex of long bones, or at least one first-degree relative with type 1 neurofibromatosis as defined by the above criteria.33 The presence of any other neoplasms commonly associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis, such as meningioma, colorectal carcinoma, ampullary gangliocytic paraganglioma, ampullary somatostatinoma, and pheochromocytoma was also noted. Pathologic materials from previous or subsequent specimens documenting the presence of type 1 neurofibromatosis were available for review in all cases. All of the patients underwent complete surgical resection of all of their GISTs at the time of the diagnostic procedure. Clinical information regarding the patients’ gender, age, medical history, presenting symptoms, and outcome was obtained from the patients’ physicians, medical records, surgical pathology reports, and operative notes.

Pathologic and Immunohistochemical Evaluation

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides cut from routinely processed (10% buffered formalin) paraffin-embedded tissue sections were available for review in all cases. Immunostains for a panel of antibodies (Table 1) were utilized to evaluate the tumors and were performed on 4 μm thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the standard avidin–biotin complex technique. Sections of normal colon served as positive controls for vimentin, muscle actins, desmin, keratin, S-100 protein, CD34, and CD117.

DNA Isolation

Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from 10 tumors were evaluated. Five to six 5-μm sections were cut from each paraffin block. The sections were deparaffinated by adding 1200 μl of xylene, vortexing for 1 min and then centrifuging at full speed for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed and 1200 μl of ethanol was added to each sample. The samples were again vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at full speed for 10 min. After removing the supernatant, the samples were allowed to dry at room temperature overnight. Total cellular DNA was isolated using the protocol accompanying the Qiagen DNeasy™ Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA).

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Amplification and Sequencing

After isolation, genomic DNA from each case was subjected to PCR using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and primers for KIT exons 9, 11, 13, and 17 as well as PDGFRA exons 12 and 18 (Table 2). The PCR conditions used for amplification of various KIT and PDGFRA exons were as follows: the samples were incubated for 4 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, the relevant annealing temperature for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; and finally incubated at 72°C for 30 min. The PCR products were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using the Qiaquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) prior to sequencing.

All sequencing reactions were performed from both forward and reverse directions using a 10 pmol PCR-primer concentration per reaction. Each ABI sequence was compared to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Human KIT and PDGFRA gene nucleotide sequences to determine the presence, type, and location of a mutation. In those cases that contained mutations, the PCR amplification and sequencing studies were repeated to confirm the results.

Results

Study Cases

Case 1

The patient was a 48-year-old man with a history of type 1 neurofibromatosis who presented with right upper quadrant pain, night sweats, and a 20 pound weight loss. He had multiple cutaneous neurofibromas and pigmented macules ranging up to 4 cm in diameter. His mother, brother, and sister all suffered from type 1 neurofibromatosis, but lacked gastrointestinal manifestations of this disease. Radiographic imaging revealed an 8 cm mass in the duodenum as well as greater than 10 serosal and mural nodules in the small intestine, all of which were resected and determined to be GISTs. Based upon morphologic differences between the largest and smaller tumors in the small intestine, the lesions were interpreted to represent synchronous primary lesions rather than metastases. The patient developed recurrent GIST in the retroperitoneum 14 months after resection and died 35 months after surgical resection. The primary findings at autopsy included disseminated GIST involving the lungs, liver, retroperitoneum, small intestine, and pancreas, as well as numerous cutaneous neurofibromas (Figure 1).

The patient (Case 1) had innumerable cutaneous tumors characterized by a spindle cell proliferation within the dermis and subcutaneous fat (a). The tumors were composed of a diffuse proliferation of spindle cells with elongate cytoplasm and ‘buckled’ nuclei admixed with numerous mast cells and were morphologically consistent with neurofibromas. An entrapped nerve is present at the top of the field (b).

Case 2

This 86-year-old woman presented with increasing abdominal pain and abdominal fullness secondary to a 10 cm ovarian cyst. Upon physical examination, she was found to have innumerable fleshy cutaneous nodules involving the scalp, face, trunk, and limbs with sparing of the mucosal surfaces. She had one son that was similarly afflicted with cutaneous lesions. The patient was taken to the operating room for a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy procedure, at which time she was noted to have three mural and subserosal nodules involving the small intestine, ranging from 0.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter, all of which were resected. At the time of the procedure, one of the cutaneous lesions was also sampled and found to be a neurofibroma. Pathologic evaluation of the small intestinal tumors confirmed the diagnosis of multiple GISTs. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Case 3

This patient was a 48-year-old male with moderate cognitive deficits and type 1 neurofibromatosis characterized by the presence of hundreds of cutaneous neurofibromas and pigmented macules over the entire skin surface. He presented for colonoscopic evaluation following completion of chemoradiation therapy for a T3, N1 rectal adenocarcinoma resected 18 months prior. Upon colonoscopy, he was found to have a suspicious, ulcerative lesion in the sigmoid colon and subsequently underwent surgical exploration and a complete colectomy. At the time of laparotomy, the patient was found to have five serosal tumors on the distal ileum, which ranged from 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter, all of which were resected. The colonic mass was an invasive adenocarcinoma and the ileal tumors were GISTs. The patient subsequently underwent upper endoscopic evaluation of the ampulla of Vater and was found to have a duodenal somatostatinoma. At 6 months after resection of the GISTs, the patient developed multiple liver metastases from his colonic adenocarcinoma, but did not have any evidence of recurrent GIST 12 months after surgical resection.

Pathologic Findings

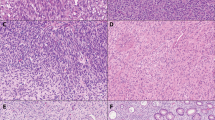

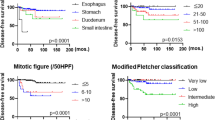

One patient had three synchronous GISTs, one had five tumors, and one had greater than 10 tumor nodules, all of which were located in the duodenum or small intestine. The mean tumor size was 0.8 cm (range: 0.3–8.0 cm). Although the largest tumor had a heterogenous cut surface with areas of hemorrhage and cystic degeneration, all of the other lesions were relatively small, homogeneous, and tan-white (Figure 2). All of the tumors were composed predominantly of spindle cells arranged in short intersecting fascicles or organoid nests, similar to sporadic GISTs. Although the largest tumor was overtly malignant with >9 mitoses/10 high-power fields, severe cytologic atypia, and necrosis (Case 1); all of the others were relatively low grade, with inconspicuous mitotic activity (<5 mitoses/50 high-power fields) and bland nuclear features (Figure 3). In most instances, the tumors were hypocellular with abundant hyalinized matrix, which was calcified in one case. In one case (Case 2), aggregates of hyperplastic interstitial cells of Cajal were present at the peripheries of the tumors and merged imperceptibly with the smooth muscle fibers of the muscularis propria, but no obvious hyperplasia of the interstitial cells of Cajal within the myenteric plexus was identified between the tumors (Figure 4).

The immunohistochemical results are summarized in Table 3. All of the GISTs demonstrated diffuse positivity for CD117 and CD34 (Figure 5). None of the tumors expressed desmin, smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, S-100 protein, or keratin markers.

Molecular Studies

The results of the PCR and DNA sequencing analyses are enumerated in Table 4. Briefly, 10 tumors (3, 3, and 4 nodules from Cases 1, 2, and 3, respectively, including the malignant tumor from Case 1) were wild type for exons 9, 13, and 17 of the KIT gene and exons 12 and 18 of the PDGFRA gene. Identical point mutations were identified in three tumors from one patient (Case 1) in exon 11 of the KIT gene, whereas all of the other tumors were wild type at this locus (Figure 6).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the clinical, pathologic, and molecular features of a series of multiple GISTs from patients with clinically and pathologically confirmed diagnoses of type 1 neurofibromatosis. All of the tumors stained strongly and diffusely for CD117 and CD34, were negative for desmin, actins, S-100 protein, and keratins, and were morphologically indistinguishable from sporadic GISTs. We evaluated 10 tumors for the presence of KIT and PDGFRA mutations at loci in which mutations have been previously described in sporadic GISTs.10, 34, 35 We found identical point mutations at KIT exon 11 in three different tumors from one patient, including a malignant GIST, whereas all of the tumors from the other two patients were wild type at this locus. All of the tumors were wild type at all of the other loci evaluated. Our results indicate that KIT mutations may play a role in the pathogenesis of GISTs among some patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis. However, most GISTs associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis reported to date do not have mutations in the KIT gene and likely arise via a different pathogenetic mechanism than that of sporadic GISTs.31

GISTs are unique mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract with characteristic morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular features.3, 4, 11, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 Most sporadic tumors arise in the stomach, followed in frequency by the small intestine and, more rarely, the colon, esophagus, anus, biliary structures, and extraintestinal soft tissues. The morphologic and immunophenotypic features of GISTs have been thoroughly described in the literature: the majority show strong and diffuse staining for CD117 and CD34, but are typically negative for desmin and S-100 protein.6, 8, 36, 38, 40, 41, 42 Approximately 75–80% of GISTs harbor activating mutations in the KIT tyrosine kinase receptor, particularly in exons 9 (extracellular domain), 11 (juxtamembrane domain), 13 (TK I domain), and 17 (TK II domain); whereas many GISTs that lack KIT mutations contain intragenic activating mutations in a related tyrosine kinase receptor, PDGFRA, in exons 12 or 18.10, 11, 13, 39, 43, 44

Most GISTs occur in a sporadic fashion. However, multifocal GISTs usually arise in specific settings, such as KIT or PDGFRA germline mutations, and in patients with intestinal neuronal dysplasia or type 1 neurofibromatosis.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 27, 31, 32, 35, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51 These patients usually develop tumors in the small intestine, which may be associated with hyperplasia of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Patients with KIT germline mutations may also have skin or mucous membrane hyperpigmentation as well as mast cell proliferations and, similar to sporadic tumors, most of their GISTs contain mutations in exon 11, although mutations involving exons 13 and 17 have been described as well.5, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21

Type 1 neurofibromatosis is a relatively common autosomal dominant inherited disorder with a prevalence of approximately one in 3000 live births in Western countries.33 The syndrome results from inherited or spontaneous germline mutations in the NF gene located at chromosome 17q11.2, which encodes the tumor suppressor gene, neurofibromin.26, 32, 52, 53, 54, 55 In addition to multiple cutaneous and deep-seated neurofibromas, patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis develop other evidence of the disease, including skin manifestations (axillary freckling, café au lait spots), neurological disorders (cognitive deficits and seizures), extraintestinal neoplasms (pheochromocytomas, tumors of the central nervous system), and neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract (ampullary adenomas and adenocarcinomas, somatostatinomas, gangliocytic paragangliomas, colorectal carcinomas, and GISTs).26, 31, 32, 33

The association between GISTs and type 1 neurofibromatosis has been well established, however, the frequency with which GISTs occur in this setting is not entirely clear.22, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, 51, 56, 57, 58 In one autopsy study of greater than 27,000 patients, 3/12 (25%) patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis had multiple GISTs, whereas clinical studies indicate that GISTs are identified in 5–25% of patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis.25, 27, 59 The GISTs in these patients have a predilection for the small intestine; tumors originating in the stomach and colon are less common. Unfortunately, most reports of patients with multiple GISTs and type 1 neurofibromatosis predate the recent technical advances in DNA extraction from paraffin-embedded tissues and, therefore, lack information regarding potential mutations in genes that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of GISTs.

In 2003, Kinoshita et al evaluated a series of GISTs from patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis for the presence of KIT mutations.31 In that study, the authors evaluated KIT exons 9, 11, 13, and 17 in 29 GISTs from seven patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis as well as the NF gene in a series of sporadic GISTs resected from patients without neurofibromatosis. They found that all of the GISTs from neurofibromatosis patients lacked KIT mutations and that the NF gene was not altered in sporadically occurring GISTs. Based on this information, the authors suggested that sporadic GISTs and those associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis arise via two mutually exclusive pathogenetic mechanisms.

In keeping with this hypothesis, two of the patients in the current study lacked KIT and PDGFRA mutations in multiple loci evaluated, but one had multiple GISTs that shared the same V559D point mutation in the juxtamembrane domain (KIT exon 11) that has been previously reported in two different studies of multiple GISTs from patients with germline KIT mutations.14, 18 Given this result, as well as the occurrence of cutaneous pigmentation and multiple GISTs in patients with germline KIT mutations, one might argue that the patient reported herein did not have type 1 neurofibromatosis, but suffered from a germline mutation in the KIT gene. However, we believe that the clinical and pathologic findings in this case support the diagnosis of type 1 neurofibromatosis. This patient had multiple pathologically confirmed neurofibromas and pigmented cutaneous macules (café au lait spots), as well as several first-degree relatives similarly affected with skin manifestations of the disease, thereby satisfying the clinical criteria for type 1 neurofibromatosis.33 Moreover, none of the other afflicted family members developed multiple GISTs, suggesting that they did not have germline KIT mutations. Therefore, we believe that our results reflect that only a limited number of type 1 neurofibromatosis patients with multiple GISTs have been evaluated using molecular techniques and, thus, it is possible, if not likely, that future studies may identify KIT mutations in a subset of type 1 neurofibromatosis patients with multiple GISTs.

In summary, we report the clinical, pathologic and molecular features of a series of patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis who also had multiple GISTs. Our results indicate that GISTs occurring in this setting are morphologically and immunohistochemically similar to sporadic GISTs. The results of our molecular studies demonstrate the presence of the same KIT mutation in multiple GISTs from one patient and wild-type KIT and PDGFRA in the remaining two patients. We conclude that most GISTs that occur in association with type 1 neurofibromatosis do not have the same molecular abnormalities present in sporadic GISTs and, therefore, likely arise via different pathogenetic mechanisms. Some of these tumors, however, do have KIT mutations, suggesting that this pathway is active in the evolution of GISTs in some patients with type 1 neurofibromatosis.

References

Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 1998;279:577–580.

Hirota S, Isozaki K, Nishida T, et al. Effects of loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations of c-kit on the gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol 2000;35 (Suppl 12): 75–79.

Hirota S . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: their origin and cause. Int J Clin Oncol 2001;6:1–5.

Hirota S, Nishida T, Isozaki K, et al. Gain-of-function mutation at the extracellular domain of KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. J Pathol 2001;193: 505–510.

Kinoshita K, Isozaki K, Hirota S, et al. c-kit gene mutation at exon 17 or 13 is very rare in sporadic gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;18:147–151.

Kitamura Y, Hirota S, Nishida T . Molecular pathology of c-kit proto-oncogene and development of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1998; 87:282–286.

Kitamura Y, Hirota S, Nishida T . A loss-of-function mutation of c-kit results in depletion of mast cells and interstitial cells of Cajal, while its gain-of-function mutation results in their oncogenesis. Mutat Res 2001;477:165–171.

Kitamura Y, Hirota S, Nishida T . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): a model for molecule-based diagnosis and treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Sci 2003;94:315–320.

Nakahara M, Isozaki K, Hirota S, et al. A novel gain-of-function mutation of c-kit gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology 1998;115:1090–1095.

Taniguchi M, Nishida T, Hirota S, et al. Effect of c-kit mutation on prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res 1999;59:4297–4300.

Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 2003;299:708–710.

Hirota S, Ohashi A, Nishida T, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology 2003;125:660–667.

Yamamoto H, Oda Y, Kawaguchi K, et al. c-kit and PDGFRA mutations in extragastrointestinal stromal tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the soft tissue). Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:479–488.

Beghini A, Tibiletti MG, Roversi G, et al. Germline mutation in the juxtamembrane domain of the kit gene in a family with gastrointestinal stromal tumors and urticaria pigmentosa. Cancer 2001;92:657–662.

Hirota S, Okazaki T, Kitamura Y, et al. Cause of familial and multiple gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors with hyperplasia of interstitial cells of Cajal is germline mutation of the c-kit gene. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:326–327.

Hirota S, Nishida T, Isozaki K, et al. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors associated with dysphagia and novel type germline mutation of KIT gene. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1493–1499.

Isozaki K, Terris B, Belghiti J, et al. Germline-activating mutation in the kinase domain of KIT gene in familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Pathol 2000; 157:1581–1585.

Maeyama H, Hidaka E, Ota H, et al. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor with hyperpigmentation: association with a germline mutation of the c-kit gene. Gastroenterology 2001;120:210–215.

Nishida T, Hirota S, Taniguchi M, et al. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumours with germline mutation of the KIT gene. Nat Genet 1998;19:323–324.

Chen H, Hirota S, Isozaki K, et al. Polyclonal nature of diffuse proliferation of interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with familial and multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut 2002;51:793–796.

Handra-Luca A, Flejou JF, Molas G, et al. Familial multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumours with associated abnormalities of the myenteric plexus layer and skeinoid fibres. Histopathology 2001;39:359–363.

Boldorini R, Tosoni A, Ribaldone R, et al. Intestinal stromal tumors with skenoid fibers in patients with type I neurofibromatosis: histological and ultrastructural evaluation of a case. Pathologica 2000;92:132.

Boldorini R, Tosoni A, Leutner M, et al. Multiple small intestinal stromal tumours in a patient with previously unrecognised neurofibromatosis type 1: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evaluation. Pathology 2001;33:390–395.

Cox JG, Royston CM, Sutton DR . Multiple smooth muscle tumours in neurofibromatosis presenting with chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Postgrad Med J 1988;64:149–151.

Fuller CE, Williams GT . Gastrointestinal manifestations of type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen's disease). Histopathology 1991;19:1–11.

Feldkamp MM, Gutmann DH, Guha A . Neurofibromatosis type 1: piecing the puzzle together. Can J Neurol Sci 1998;25:181–191.

Giuly JA, Picand R, Giuly D, et al. Von Recklinghausen disease and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg 2003;185:86–87.

Hochberg FH, Dasilva AB, Galdabini J, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement in von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Neurology 1974;24:1144–1151.

Ishida T, Wada I, Horiuchi H, et al. Multiple small intestinal stromal tumors with skeinoid fibers in association with neurofibromatosis 1 (von Recklinghausen's disease). Pathol Int 1996;46:689–695.

Ishizaki Y, Tada Y, Ishida T, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine associated with von Recklinghausen's disease: report of a case. Surgery 1992;111:706–710.

Kinoshita K, Hirota S, Isozaki K, et al. Absence of c-kit gene mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumours from neurofibromatosis type 1 patients. J Pathol 2004; 202:80–85.

Riccardi VM . Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med 1981;305:1617–1627.

Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol 1988;45:575–578.

Kurokawa Y, Nishisho I, Kawahara K, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum with activating mutation of c-kit: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1316–1318.

Nishida T, Hirota S . Biological and clinical review of stromal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. Histol Histopathol 2000;15:1293–1301.

Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol 2002;33:459–465.

Greenson JK . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors and other mesenchymal lesions of the gut. Mod Pathol 2003;16:366–375.

Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, et al. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol 1998;152:1259–1269.

Lux ML, Rubin BP, Biase TL, et al. KIT extracellular and kinase domain mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Pathol 2000;156:791–795.

Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J . Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recent advances in understanding of their biology. Hum Pathol 1999;30:1213–1220.

Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Sarlomo-Rikala M . Immunohistochemical spectrum of GISTs at different sites and their differential diagnosis with a reference to CD117 (KIT). Mod Pathol 2000;13:1134–1142.

Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Barusevicius A, et al. CD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol 1998;11:728–734.

Singer S, Rubin BP, Lux ML, et al. Prognostic value of KIT mutation type, mitotic activity, and histologic subtype in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3898–3905.

Antonescu CR, Sommer G, Sarran L, et al. Association of KIT exon 9 mutations with nongastric primary site and aggressive behavior: KIT mutation analysis and clinical correlates of 120 gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:3329–3337.

Miettinen M, Kopczynski J, Makhlouf HR, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas in the duodenum: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 167 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:625–641.

Robson ME, Glogowski E, Sommer G, et al. Pleomorphic characteristics of a germ-line KIT mutation in a large kindred with gastrointestinal stromal tumors, hyperpigmentation, and dysphagia. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:1250–1254.

Jeng YM, Mao TL, Hsu WM, et al. Congenital interstitial cell of cajal hyperplasia with neuronal intestinal dysplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1568–1572.

O’Brien P, Kapusta L, Dardick I, et al. Multiple familial gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors and small intestinal neuronal dysplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23:198–204.

Chompret A, Kannengiesser C, Barrois M, et al. PDGFRA germline mutation in a family with multiple cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Gastroenterology 2004;126:318–321.

Walsh NM, Bodurtha A . Auerbach's myenteric plexus. A possible site of origin for gastrointestinal stromal tumors in von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1990;114:522–525.

Min KW, Balaton AJ . Small intestinal stromal tumors with skeinoid fibers in neurofibromatosis: report of four cases with ultrastructural study of skeinoid fibers from paraffin blocks. Ultrastruct Pathol 1993;17:307–314.

Cawthon RM, Weiss R, Xu GF, et al. A major segment of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene: cDNA sequence, genomic structure, and point mutations. Cell 1990; 62:193–201.

Viskochil D, Buchberg AM, Xu G, et al. Deletions and a translocation interrupt a cloned gene at the neurofibromatosis type 1 locus. Cell 1990;62: 187–192.

Wallace MR, Marchuk DA, Andersen LB, et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science 1990;249:181–186.

Xu GF, O'Connell P, Viskochil D, et al. The neurofibromatosis type 1 gene encodes a protein related to GAP. Cell 1990;62:599–608.

Rizzo S, Bonomo S, Moser A, et al. Bilateral pheochromocytoma associated with duodeno-jejunal GIST in patient with von Recklinghausen disease: report of a clinical case. Chir Ital 2001;53:243–246.

Sakaguchi N, Sano K, Ito M, et al. A case of von Recklinghausen's disease with bilateral pheochromocytoma-malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the adrenal and gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:889–897.

Schaldenbrand JD, Appelman HD . Solitary solid stromal gastrointestinal tumors in von Recklinghausen's disease with minimal smooth muscle differentiation. Hum Pathol 1984;15:229–232.

Ghrist TD . Gastrointestinal involvement in neurofibromatosis. Arch Intern Med 1963;112:357–362.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yantiss, R., Rosenberg, A., Sarran, L. et al. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors in type I neurofibromatosis: a pathologic and molecular study. Mod Pathol 18, 475–484 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800334

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800334

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Jejunal gastrointestinal stromal tumor that developed in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report

Diagnostic Pathology (2023)

-

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Japanese patients with neurofibromatosis type I

Journal of Gastroenterology (2016)

-

Association of multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and gastric schwannoma in a patient with type 1 neurofibromatosis

Journal Africain d'Hépato-Gastroentérologie (2015)

-

Periampullary and Duodenal Neoplasms in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Two Cases and an Updated 20-Year Review of the Literature Yielding 76 Cases

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2010)

-

c-KIT positive Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor presenting with acute bleeding in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report

International Seminars in Surgical Oncology (2009)