Abstract

The prevalence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus is increasing worldwide. Both diseases lead to severe complications such as cardiovascular and chronic kidney diseases, which increase the risk of death over a long period of time. Therefore, the prevention and aggravation of hypertension and diabetes mellitus are major challenges. Because few review articles have focused on the epidemiological perspective of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, we reviewed major observational studies mainly from Japan and from Western countries that have reported on the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, the binominal risk of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and the risk of their coexistence. Our investigation found that approximately 50% of diabetic patients had hypertension, and approximately 20% of hypertensive patients had diabetes mellitus. Those with either hypertension or diabetes mellitus had a 1.5- to 2.0-fold higher risk of having both conditions. These results were similar for both Japan and Western countries. Although comparing the results between Japan and Western countries was difficult because the risks were estimated using widely varying statistical analyses, it was revealed that the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus certainly increased the risk of complications regardless of the country. The definition, prevalence and medical treatment of hypertension and diabetes mellitus will change in the future. For early intervention based on the latest evidence to prevent severe complications, it is important to accumulate epidemiological knowledge of hypertension and diabetes mellitus and to update the evidence for both Japan and other countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension and diabetes mellitus are characterized by different pathophysiologies, but they have much in common. Both are categorized as non-communicable diseases caused by similar unhealthy lifestyles, such as heavy alcohol consumption,1, 2 physical inactivity3, 4 and obesity5, 6 in addition to genetic factors. Insulin resistance is also well known as an intermediate factor between unhealthy lifestyles and incidences of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus.7 Therefore, strategies for prevention and target populations overlap. In addition, complications are similar because both diseases influence whole-body circulation. Furthermore, both hypertension and diabetes mellitus are globally prevalent and increase the risk of complications, which lead to severe diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) that lead to the risk of death over a long period.8, 9, 10

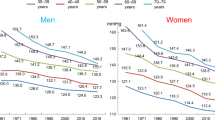

The prevalence of both hypertension and diabetes mellitus is increasing worldwide, and from 1975 to 2015, diabetes increased by 4.5%.11 Although the age-standardized percentage of hypertension decreased from 1975 to 2015, the number of hypertensive individuals increased from 594 million in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015 because of population growth and increasingly aging population.12 The Non-communicable Disease Risk Factor Collaboration has estimated the age-standardized prevalence of hypertension (systolic blood pressure ⩾140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ⩾90 mm Hg) in 2015 by region, sex and age groups in 5-year increments among adults aged 18 years or older.12 The report stated that the prevalence of hypertension in men and women aged 50–54 years was, respectively, 32.8% and 29.7% worldwide, 26.3% and 14.0% in high-income Asia-Pacific countries including Japan, 37.1% and 39.5% in South Asia, 27.1% and 17.7% in high-income Western countries, and 46.2% and 35.0% in Central and Eastern Europe.12 The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in 2015 by region has been reported by the International Diabetes Federation; the diabetes global prevalence was 8.8% among adults aged 20–79 years, and the age-adjusted comparative diabetes prevalence by region was 8.8% in Western Pacific countries including Japan, 7.3% in Europe and 11.5% in North America and the Caribbean.13

Consequently, the prevention of the incidence and aggravation of hypertension and diabetes mellitus are major challenges. Although there are review articles discussing hypertension and diabetes mellitus, few studies have focused on the epidemiological perspective of the two diseases.14, 15, 16 Furthermore, no study has focused on ethnic differences. In Asia, stroke incidence is more frequent than the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD). Because hypertension has a stronger impact on stroke than CHD, the linear relationship between blood pressure and risk of CVD is steeper in Asia than in Western countries.17 Therefore, this study discusses the epidemiological perspective of the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus by reviewing observational studies of Asia (mainly Japan) and comparing the findings to major studies of Western countries.

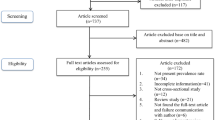

Prevalence of coexistence

We selected major studies from the literature and reviewed the prevalence of the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus reported in Japanese and Western cohort studies with large sample sizes. Table 1 shows the percentages of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and their coexistence.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 The table also includes our newly calculated percentages using the number of participants and the percentages shown in the studies. For example, in the report showing the prevalence of hypertension according to diabetes categories, the percentage of diabetes mellitus in hypertensive patients was calculated as follows: (number of hypertensive patients in the diabetes category)/(the sum of hypertensive patients in each category) × 100 (Figure 1). We rounded the calculated number of participants to whole numbers. However, we did not calculate the percentages of hypertension or diabetes mellitus in studies involving only participants with hypertension or diabetes mellitus.25, 26, 27, 31, 33 The ages of participants shown in Table 1 are presented as ranges or averages according to the description in the original studies. The terms for blood glucose and hypertension, such as fasting glucose level or fasting blood glucose and white coat hypertension or isolated office hypertension, are also presented according to the term used in the original studies.

Hypertension in diabetes mellitus

Among seven Japanese studies reporting the prevalence of hypertension,18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 four reported approximately 50% of diabetic patients had hypertension.18, 19, 20, 21 The Hisayama study reported lower percentages than the others, which was due to using higher levels of blood pressure (⩾160/95 mm Hg) to define hypertension than in the other studies.22 Meanwhile, the National Integrated Project for Prospective Observation of Non-communicable Disease and its Trends in the Aged 80 (NIPPON DATA80) and the Tanno-Sobetsu study that collected data ~1980 reported a higher prevalence of hypertension.23, 24 Because the mean systolic blood pressure decreased during the past few decades in Japan,36 it may be that these two studies would report higher prevalence of hypertension than the later studies.

In other studies mainly conducted in Western countries, the Strong Heart Study and Honolulu Heart Study reported close to 50% prevalence of hypertension.28, 29 The population of the Honolulu Heart Study was of Japanese ancestry, which may be the reason for the similar prevalence to the Japanese study.29 The Framingham study reported a slightly higher prevalence because hypertension was defined as a lower level of blood pressure (⩾130/80 mm Hg) for diabetic patients.30 Other studies reported higher than 50% prevalence of hypertension in diabetic patients.31, 32, 33, 34, 35 Possible explanations for the difference may be the additional ambulatory measurement of blood pressure for defining hypertension or a high prevalence of hypertension in the study population.

In addition, it is hypothesized that the duration of hypertension or diabetes mellitus is associated with the prevalence of coexistence. Because changes caused by hypertension and diabetes mellitus, such as microvascular damage, sympathetic damage, an enhanced renin–angiotensin system and decreased insulin sensitivity, all aggravate hypertension and diabetes mellitus,37, 38, 39 the longer the duration increases the risk of coexistence. As discussed later, high risks of the future coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in hypertensive or diabetic patients may indicate that patients with long duration of one or the other condition are more likely to acquire the other disease.

Diabetes mellitus in hypertension

Among nine Japanese studies,18, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study, NIPPON DATA80 and the Suita study used a single blood test for the definition of diabetes mellitus and reported a prevalence of approximately 10% with diabetes mellitus in hypertensive patients.19, 21, 23 The Funagata,18 Ohasama20 and Toyama et al.25 studies of hypertensive patients used a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test to define diabetes (which was only partially used in the Ohasama study) and reported approximately 20% with diabetes mellitus. Although the Tanno-Sobetsu study also used an oral glucose tolerance test, the prevalence of hypertension was lower than in the other three studies possibly because the amount of glucose used in the tolerance test was 50 g.24 The prevalence of diabetes mellitus reported in treated hypertensives studies, that is, the Home blood pressure measurement with Olmesartan-Naive patients to Establish Standard Target blood pressure (HONEST) study and the Japan Home vs. Office blood pressure Measurement Evaluation (J-HOME) study, did not differ from the previously mentioned studies, even though the definitions of diabetes mellitus were based on information from physicians.26, 27

In other studies, mainly conducted in Western countries, the Swiss Hypertension and Risk Factor Program, the International Database on Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes (IDACO) and the study by Banegas et al.33 reported a similar prevalence of diabetes compared with Japanese studies with a similar definition of diabetes mellitus.31,32 The study by Hu et al.34 and the Honolulu study29 using self-reporting for the definition of diabetes mellitus reported relatively low percentages. In the two studies, undiagnosed diabetes mellitus might have been overlooked. Despite the definition of diabetes mellitus by a single blood test or by self-reported medication, the Framingham study reported a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus in hypertensive patients.30 In addition to a relatively high prevalence of hypertension in the Framingham study population, there was a considerable difference in the mean age between those with diabetes mellitus (61.8 years) and those without diabetes mellitus (45.9 years) among hypertensive patients.30 Because the prevalence of diabetes mellitus increases with age, this finding might be a reason for the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus in hypertensive patients. The Strong Heart Study, whose participants were American Indians living in Arizona, reported a remarkably high percentage (53.7%).28 Pima Indians who reside on the eastern position of the Gila River Indian Reservation in Central Arizona are well known for having an enormously high prevalence of diabetes mellitus; the prevalence was approximately 50% among those aged 35 years and older.40, 41 This population has a 19-fold higher incidence of diabetes compared with the white population of Rochester, Minnesota.42 Therefore, the high percentage reported by the Strong Heart Study might have been a reflection of the characteristics of the region. The Jackson Heart Study involving blacks and including glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels as well as fasting glucose levels for the definition of diabetes mellitus also reported a relatively high percentage of diabetes mellitus in hypertensive patients.35 Because individuals with high fasting glucose levels and high HbA1c are not often overlapped,43 the number of diabetes mellitus increased when using the two indices. In addition, blacks had a higher prevalence of diabetes compared with whites in the United States, which may be a reason for the high prevalence of diabetes in the Jackson Heart Study.44

Bidirectional risk

Many studies have investigated the risk of hypertension for diabetes incidence45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 (Table 2). In Asian studies, Japanese and Korean studies have reported a significantly (1.3–1.8 times) higher risk of hypertension for diabetes incidence compared with normotensive individuals, whereas the Chinese study did not report a high risk.45, 46, 47 Possible explanations for the inconsistency are the inclusion of many more variables and the inclusion of younger individuals in the Chinese study47 compared with the Japanese45 and Korean46 studies. In addition, the participants at risk in the Chinese study did not include individuals with prediabetes, who are at high risk of developing diabetes.

In other studies mainly conducted in Western countries,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 many have reported 1.4–2.2 times higher risk of hypertension for diabetes incidence. Although the risk of hypertension might be slightly higher in Western countries than in Asian countries, it is difficult to confirm the ethnic difference because there are other differences such as the methods of hypertension categorization or adjustment variables. The Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) is the only study to have reported close to a 2.0 times higher risk of masked hypertension for diabetes incidence compared with those without white coat hypertension and masked hypertension.49 If a high risk of masked hypertension for diabetes incidence is considered, the risk of hypertension reported by other studies that used office blood pressure alone might be underestimated because other studies included masked hypertension in the reference group.

Although there have been many studies investigating the risk of hypertension for diabetes incidence, there have been few studies investigating the risk of diabetes mellitus for the incidence of hypertension. The Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study is the only one to have reported the risk of diabetes in relation to the incidence of hypertension (n=7329, median follow-up of 10.1 years); the multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for incidence of hypertension were 1.25 (1.02–1.54) in prediabetics and 1.92 (1.47–2.51) in diabetics compared individuals with normal glucose tolerance.52 In addition, Janghorbani et al.55 reported that those with prediabetes had a high risk for the incidence of hypertension; multivariable adjusted HRs and 95% CI for the incidence of hypertension were 1.54 (1.33–1.77) in those with impaired glucose tolerance (fasting glucose level <126 mg dl−1, 2 h glucose level after a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test 140–199 mg dl−1) and 1.23 (1.01–1.50) in those with impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose level 100–126 mg dl−1, 2- h glucose level after 75- g oral glucose tolerance test <140 mg dl−1) compared with normal glucose tolerance (fasting glucose level <100 mg dl−1, 2- h glucose level after 75- g oral glucose tolerance test <140 mg dl−1). There was no difference in the risk for prediabetes between the two studies. Further studies are needed to confirm the risk of diabetes for hypertension incidence.

Risk for macrovascular and microvascular diseases

It is well known that both hypertension and diabetes mellitus increase the risks for macrovascular disease such as CVD, stroke and CHD, and microvascular diseases such as kidney disease and retinopathy. The coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus is naturally supposed to increase risk. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study involving diabetic patients estimated the risk of an increase in systolic blood pressure for incidence of any diabetic complications, including both macrovascular (stroke, myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure or angina) and microvascular diseases (renal failure, lower extremity amputation or death from peripheral vascular disease, death from hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal photocoagulation and cataract extraction): the HR was 1.12 (P<0.001) per 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure.56 The UK Prospective Diabetes Study also reported that patients with an HbA1c ⩾8% and a systolic blood pressure ⩾150 mm Hg had a 16.3 times higher risk of microvascular disease, including retinal photocoagulation, vitreous hemorrhage and fatal or non-fatal renal failure, compared with patients with HbA1c <6% and systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.57 Other studies have shown the risk of the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus with respect to each complication.21, 26, 30, 34, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69 To estimate the risk of the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, some studies analyzed the combination categories of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and other studies analyzed via stratifications. Tables 3, Tables 4, 5 show the risks of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for macrovascular disease reported by the cohort studies. Incidence rates are shown for the studies that did not estimate the risk. Because the number of studies investigating the risk for microvascular disease was smaller than that for macrovascular disease, the results for microvascular disease are not shown.

Risk of the coexistence for CVD

Table 3 shows the risk for the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for CVD. As reported by the Suita study, which is a population-based cohort study, the risk of the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for CVD incidence was approximately 5 times higher than for the population without hypertension and diabetes mellitus.21 The HONEST study, involving hypertensive patients, estimated an approximately 2.8 times higher risk for CVD incidence among those with uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes compared with those with controlled hypertension and without diabetes mellitus.26 In the study reported by Iso et al.,58 although it may be an overestimation because confounding factors were not adjusted, the crude incidence rate of the coexistence for ischemic stroke was approximately 6.5 times higher than for those without hypertension and diabetes mellitus (1.2 vs. 7.9).

In other studies, mainly conducted in Western countries, the multivariable adjusted risk of the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for ischemic stroke was reported as 3.0–4.5 times higher compared with those without hypertension and diabetes mellitus by the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study59 and the study by Hu et al.60 The risk for CHD was reported by Hu et al.34 as approximately 2–3 times higher in men and 6–7 times higher in women compared with those without hypertension and diabetes mellitus. According to the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, age- and race-adjusted CHD incidence rates of those with hypertension and diabetes mellitus were approximately 3 times higher in men (9.9 vs. 28.4) and 7 times higher in women (2.7 vs. 18.7) compared with those without hypertension and diabetes mellitus.61 Although the statistical methods for risk estimation were different in these two studies, the degrees of risk seemed to be similar.

Risk of hypertension for CVD in diabetic patients

Table 4 shows the risk of hypertension for CVD in patients with diabetes mellitus. According to the Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS) involving Japanese diabetic patients, the risk for stroke incidence increased 1.18 times higher per 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure.62 Although the JDCS also estimated the risk for CHD per 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure in diabetic patients, the risk was not significantly increased, probably because of the small number of events.62 The Hypertension Objective Treatment Based on Measurement by Electrical Devices of Blood Pressure (HOMED-BP) study involving Japanese hypertensive patients with impaired glucose metabolism showed that the risk for CVD incidence and death increased 1.68 times per 1 s.d. increment of the home systolic blood pressure.63 The Asia-Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration involving Asians, Australians and Maorilanders showed that risk for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke incidence increased 1.29 and 1.56 times higher, respectively, per 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure in those with diabetes mellitus.64 In addition, the risk for CHD in Asians increased 1.27 times higher per 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure.64 Because the risk estimated by Asia-Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration was adjusted only by age, sex and cohort, this value may be an overestimation.

In other studies, mainly conducted in Western countries, the risk of hypertension or an increase in blood pressure for CVD incidence or death among diabetic patients was assessed.30, 65, 66, 67 From the Framingham study and the study by Henry et al.,66 it was reported that hypertension was associated with approximately 2- or 3-fold increased risk for CVD.30 From the NDR-BP II and IDACO studies, it was shown that an increase in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure was associated with a high risk for CVD.65, 66 For stroke incidence, the NDR-BP II and Framingham studies showed that the risk increased approximately 1.5–2.5 times higher in diabetic patients with hypertension compared with diabetic patients without hypertension.30, 65 With regard to CHD, the Framingham study reported that the risk for incidence of myocardial infarction and heart failure increased 1.89 and 1.76 times higher in diabetic patients with hypertension compared with diabetic patients without hypertension.30 The NDR-BP II and IDACO studies showed that an increase in blood pressure, especially diastolic blood pressure, was associated with increased risk for CHD.65, 66 In contrast to the Japanese studies, the high risk of hypertension for heart diseases was observed among diabetic patients in Western studies.30, 65, 66

Risk of diabetes for CVD in hypertensive patients

Table 5 shows the risk of diabetes mellitus for CVD in those with hypertension. In Japan, although it may be an overestimation because confounding factors were not adjusted, HOMED-BP reported an approximately 2-fold increased risk for CVD in patients with impaired glucose metabolism compared with normal glucose metabolism (incidence rates per 1000 person-years: 4.88 vs. 9.95).63 Iso et al.58 showed that the risk of stroke among those with hypertension and diabetes mellitus was 1.2 times higher, although without significance, than those with only hypertension. The multivariable adjusted risk of diabetes mellitus for CVD incidence or death among hypertensive patients was assessed by the Alderman et al.68 study and the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT).69 These two studies reported that diabetes mellitus was associated with approximately 2–3-fold increased risk for CVD. In Japan and other countries, the number of studies investigating the risk of diabetes compared with non-diabetes mellitus for CVD in hypertensive patients was smaller than that of studies investigating the risk of hypertension for CVD in diabetic patients.

Risk of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for kidney disease

In Japan, the JDCS reported that the risk for progression to proteinuria was 2.55 (95% CI: 0.98–6.33) times higher in diabetic patients with systolic blood pressure ⩾140 mm Hg compared with diabetic patients with systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg.70 In addition, the Japanese hospital-based prospective study (median follow-up of 11.9 years) by Takao et al.,71 involving 516 diabetic patients, reported that the risk for development of microalbuminuria was 1.39 (95% CI: 1.15–1.67) times higher per time-dependent 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure. In other countries, the Associazione Medici Diabetologi (AMD)-Annuals Study72 involving diabetic patients in Italy (n=12 995, follow-up of 4 years) reported that patients with hypertension had 1.38 (95% CI: 1.24–1.54) times higher risk for diabetic kidney disease compared with normotensive patients. The Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study in Iran (n=8059, median follow-up of 11.0 years) reported that participants with hypertension and diabetes mellitus had 1.45 (95% CI: 1.22–1.73) times higher risk for CKD compared with those without hypertension and diabetes mellitus.52

Risk of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for retinopathy

In Japan, Takao et al.71 reported that the risk for mild–moderate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy was 1.18 (95% CI: 1.01–1.37) times higher per time-dependent 10 mm Hg increments of systolic blood pressure. The JDCS, which followed 1630 diabetic patients for 8 years, reported that the systolic blood pressure per 10 mm Hg increments was associated with a 1.09 (95% CI: 1.02–1.17) times higher risk for retinopathy.73 As a result of the German/Austrian Diabetes Prospective Documentation Initiative database, hypertension (blood pressure ⩾140/80 mm Hg) had 1.15 (95% CI: 1.11–1.20) times higher risk for retinopathy.74 In addition, the cohort study of the Genetics of Diabetes Audit and Research in Tayside Scotland reported that the risk for mild background diabetic retinopathy increased 1.20 (95% CI: 1.11–1.30) times for 1 s.d. increments of systolic blood pressure among diabetic patients.75 The meta-analysis investigating the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy, diagnosed by retinal photographs among diabetic patients from 35 population-based studies, reported that the percentages of diabetic retinopathy were 31% among those with normal blood pressure and 40% among those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg or treatment for hypertension).76 Consequently, although the statistical methods were different, the high blood pressure was likely to be associated with 1.1–1.3 times higher risk for retinopathy among diabetic patients. However, no study has investigated the risk of diabetes mellitus for retinopathy among hypertensive patients.

Conclusions

We summarized major observational studies conducted in Japan and other countries (mainly Western countries) reporting the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, binominal risk of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and risk of coexistence for complications.

Among individuals with diabetes mellitus, approximately 50% had hypertension defined as a blood pressure ⩾140/90 mm Hg or the use of antihypertensive medication. Among those with hypertension, approximately 20% had diabetes mellitus, including postprandial hyperglycemia. These prevalence was similar between Japan and Western countries. Bidirectional risk of hypertension and diabetes mellitus were also similar between Japan and other countries. Individuals with either hypertension or diabetes mellitus had 1.5–2.0 times higher risk of having both conditions.

Many studies have investigated the risk of hypertension and diabetes mellitus for macrovascular and microvascular diseases. Although it was difficult to compare the results of Japan with other countries because the risks were estimated using widely varying statistical analyses, it was demonstrated that the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus clearly increased the risk for complications regardless of the country. In Japan, few studies have investigated the risk of CHD, which might be due to a small number of CHD patients for analysis using a high-power statistical test in each Japanese cohort study. Because CHD is a major disease related to cause of death in Japan, further investigations with larger sample sizes are needed.

The definition, prevalence and medical treatment of hypertension and diabetes mellitus will change in the future. For early intervention based on the latest evidence to prevent severe complications, it is important to accumulate epidemiological knowledge of hypertension and diabetes mellitus and update the evidence for both Japan and other countries.

References

Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Messerli FH . Alcohol consumption and the risk of hypertension in men and women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens 2012; 14: 792–798.

Baliunas DO, Taylor BJ, Irving H, Roerecke M, Patra J, Mohapatra S, Rehm J . Alcohol as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 2123–2132.

Huai P, Xun H, Reilly KH, Wang Y, Ma W, Xi B . Physical activity and risk of hypertension: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Hypertension 2013; 62: 1021–1026.

Smith AD, Crippa A, Woodcock J, Brage S . Physical activity and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetologia 2016; 59: 2527–2545.

Decoda Study Group, Nyamdorj R, Qiao Q, Lam TH, Tuomilehto J, Ho SY, Pitkäniemi J, Nakagami T, Mohan V, Janus ED, Ferreira SR . BMI compared with central obesity indicators in relation to diabetes and hypertension in Asians. Obesity (Silver Spring, MD) 2008; 16: 1622–1635.

Bell JA, Kivimaki M, Hamer M . Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Obes Rev 2014; 15: 504–515.

Wang F, Han L, Hu D . Fasting insulin, insulin resistance and risk of hypertension in the general population: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta 2016; 464: 57–63.

Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Thijs L, Björklund-Bodegård K, Kuznetsova T, Ohkubo T, Richart T, Torp-Pedersen C, Lind L, Jeppesen J, Ibsen H, Imai Y, Staessen JA,, IDACO Investigators. Prognostic superiority of daytime ambulatory over conventional blood pressure in four populations: a meta-analysis of 7030 individuals. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1554–1564.

Kannel WB, McGee DL . Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA 1979; 241: 2035–2038.

Yamagata K, Ishida K, Sairenchi T, Takahashi H, Ohba S, Shiigai T, Narita M, Koyama A . Risk factors for chronic kidney disease in a community-based population: a 10-year follow-up study. Kidney Int 2007; 71: 159–166.

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388: 1545–1602.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19.1 million participants. Lancet 2017; 7 389: 37–55.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th edn. Available at: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/ (last accessed 28 February 2017).

Sowers JR, Epstein M, Frohlich ED . Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: an update. Hypertension 2001; 37: 1053–1059.

Sowers JR . Diabetes mellitus and vascular disease. Hypertension 2013; 61: 943–947.

Lastra G, Syed S, Kurukulasuriya LR, Manrique C, Sowers JR . Type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: an update. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 2014; 43: 103–122.

Lawes CM, Rodgers A, Bennett DA, Parag V, Suh I, Ueshima H, MacMahon S Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration. Blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 707–716.

Oizumi T, Daimon M, Jimbu Y, Wada K, Kameda W, Susa S, Yamaguchi H, Ohnuma H, Tominaga M, Kato T . Impaired glucose tolerance is a risk factor for stroke in a Japanese sample—the Funagata study. Metabolism 2008; 57: 333–338.

Cui R, Iso H, Yamagishi K, Saito I, Kokubo Y, Inoue M, Tsugane S . Diabetes mellitus and risk of stroke and its subtypes among Japanese: the Japan public health center study. Stroke 2011; 42: 2611–2614.

Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Asayama K, Obara T, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Hoshi H, Satoh H, Imai Y . Prognosis of 'masked' hypertension and 'white-coat' hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10-year follow-up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46: 508–515.

Kokubo Y, Kamide K, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Kawanishi K, Okayama A, Kawano Y . Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita study. Hypertension 2008; 52: 652–659.

Fujishima M, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Ohmura T, Iwamoto H, Nakayama K, Ohmori S, Yoshitake T . Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in a prospective population survey in Japan: The Hisayama Study. Diabetes 1996; 45: S14–S16.

Kadowaki S, Okamura T, Hozawa A, Kadowaki T, Kadota A, Murakami Y, Nakamura K, Saitoh S, Nakamura Y, Hayakawa T, Kita Y, Okayama A, Ueshima H,, NIPPON DATA Research Group. Relationship of elevated casual blood glucose level with coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a representative sample of the Japanese population. NIPPON DATA80. Diabetologia 2008; 51: 575–582.

Iimura O . Insulin resistance and hypertension in Japanese. Hypertens Res 1996; 19: S1–S8.

Toyama M, Watanabe S, Miyauchi T, Kuroda Y, Ojima E, Sato A, Seo Y, Aonuma K . Diabetes and obesity are significant risk factors for morning hypertension: from Ibaraki Hypertension Assessment Trial (I-HAT). Life Sci 2014; 104: 32–37.

Kushiro T, Kario K, Saito I, Teramukai S, Sato Y, Okuda Y, Shimada K . Increased cardiovascular risk of treated white coat and masked hypertension in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease: the HONEST study. Hypertens Res 2017; 40: 87–95.

Obara T, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Asayama K, Metoki H, Inoue R, Oikawa T, Murai K, Komai R, Horikawa T, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Imai Y,, J-HOME Study Group. The current status of home and office blood pressure control among hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus: the Japan Home Versus Office Blood Pressure Measurement Evaluation (J-HOME) study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2006; 73: 276–283.

de Simone G, Devereux RB, Chinali M, Lee ET, Galloway JM, Barac A, Panza JA, Howard BV . Diabetes and incident heart failure in hypertensive and normotensive participants of the Strong Heart Study. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 353–360.

Rodriguez BL, Lau N, Burchfiel CM, Abbott RD, Sharp DS, Yano K, Curb JD . Glucose intolerance and 23-year risk of coronary heart disease and total mortality: the Honolulu Heart Program. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 1262–1265.

Chen G, McAlister FA, Walker RL, Hemmelgarn BR, Campbell NR . Cardiovascular outcomes in Framingham participants with diabetes: the importance of blood pressure. Hypertension 2011; 57: 891–897.

Pechère-Bertschi A, Greminger P, Hess L, Philippe J, Ferrari P . Swiss Hypertension and Risk Factor Program (SHARP): cardiovascular risk factors management in patients with type 2 diabetes in Switzerland. Blood Press 2005; 14: 337–344.

Franklin SS, Thijs L, Li Y, Hansen TW, Boggia J, Liu Y, Asayama K, Björklund-Bodegård K, Ohkubo T, Jeppesen J, Torp-Pedersen C, Dolan E, Kuznetsova T, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Tikhonoff V, Malyutina S, Casiglia E, Nikitin Y, Lind L, Sandoya E, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Filipovsky J, Imai Y, Wang J, Ibsen H, O'Brien E, Staessen JA International Database on Ambulatory blood pressure in Relation to Cardiovascular Outcomes Investigators. Masked hypertension in diabetes mellitus: treatment implications for clinical practice. Hypertension 2013; 61: 964–971.

Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, de la Sierra A, de la Cruz JJ, Gorostidi M, Segura J, Martell N, García-Puig J, Deanfield J, Williams B . High prevalence of masked uncontrolled hypertension in people with treated hypertension. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 3304–3312.

Hu G, Jousilahti P, Tuomilehto J . Joint effects of history of hypertension at baseline and type 2 diabetes at baseline and during follow-up on the risk of coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 3059–3066.

Diaz KM, Veerabhadrappa P, Brown MD, Whited MC, Dubbert PM, Hickson DA . Prevalence, determinants, and clinical significance of masked hypertension in a population-based sample of African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Am J Hypertens 2015; 28: 900–908.

The Japan Society of Hypertension. Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. The Japan Society of Hypertension, (LIFE SCIENCE CO., LTD.: Tokyo, Japan, 2014).

Feihl F, Liaudet L, Waeber B, Levy BI . Hypertension: a disease of the microcirculation? Hypertension 2006; 48: 1012–1017.

Lembo G, Napoli R, Capaldo B, Rendina V, Iaccarino G, Volpe M, Trimarco B, Saccà L . Abnormal sympathetic overactivity evoked by insulin in the skeletal muscle of patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Invest 1992; 90: 24–29.

Ogihara T, Asano T, Ando K, Chiba Y, Sakoda H, Anai M, Shojima N, Ono H, Onishi Y, Fujishiro M, Katagiri H, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Noguchi N, Aburatani H, Komuro I, Fujita T . Angiotensin II-induced insulin resistance is associated with enhanced insulin signaling. Hypertension 2002; 40: 872–879.

Bennett PH, Burch TA, Miller M . Diabetes mellitus in American (Pima) Indians. Lancet 1971; 2: 125–128.

Pavkov ME, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Krakoff J, Nelson RG . Changing patterns of type 2 diabetes incidence among Pima Indians. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1758–1763.

Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hamman RF, Miller M . Diabetes incidence and prevalence in Pima Indians: a 19-fold greater incidence than in Rochester, Minnesota. Am J Epidemiol 1978; 108: 497–505.

Saukkonen T, Cederberg H, Jokelainen J, Laakso M, Härkönen P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Rajala U . Limited overlap between intermediate hyperglycemia as defined by A1C 5.7–6.4%, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 2314–2316.

Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC . Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA 2015; 314: 1021–1029.

Waki K, Noda M, Sasaki S, Matsumura Y, Takahashi Y, Isogawa A, Ohashi Y, Kadowaki T, Tsugane S,, JPHC Study Group. Alcohol consumption and other risk factors for self-reported diabetes among middle-aged Japanese: a population-based prospective study in the JPHC study cohort I. Diabet Med 2005; 22: 323–331.

Kim MJ, Lim NK, Choi SJ, Park HY . Hypertension is an independent risk factor for type 2 diabetes: the Korean genome and epidemiology study. Hypertens Res 2015; 38: 783–789.

Qiu M, Shen W, Song X, Ju L, Tong W, Wang H, Zheng S, Jin Y, Wu Y, Wang W, Tian J . Effects of prediabetes mellitus alone or plus hypertension on subsequent occurrence of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus: longitudinal study. Hypertension 2015; 65: 525–530.

Izzo R, de Simone G, Chinali M, Iaccarino G, Trimarco V, Rozza F, Giudice R, Trimarco B, De Luca N . Insufficient control of blood pressure and incident diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 845–850.

Mancia G, Bombelli M, Facchetti R, Madotto F, Quarti-Trevano F, Grassi G, Sega R . Increased long-term risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus in white-coat and masked hypertension. J Hypertens 2009; 27: 1672–1678.

Mullican DR, Lorenzo C, Haffner SM . Is prehypertension a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1870–1872.

Stahl CH, Novak M, Lappas G, Wilhelmsen L, Björck L, Hansson PO, Rosengren A . High-normal blood pressure and long-term risk of type 2 diabetes: 35-year prospective population based cohort study of men. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2012; 12: 89.

Derakhshan A, Bagherzadeh-Khiabani F, Arshi B, Ramezankhani A, Azizi F, Hadaegh F . Different combinations of glucose tolerance and blood pressure status and incident diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e003917.

Weycker D, Nichols GA, O'Keeffe-Rosetti M, Edelsberg J, Vincze G, Khan ZM, Oster G . Excess risk of diabetes in persons with hypertension. J Diabetes Compl 2009; 23: 330–336.

Conen D, Ridker PM, Mora S, Buring JE, Glynn RJ . Blood pressure and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Women's Health Study. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 2937–2943.

Janghorbani M, Bonnet F, Amini M . Glucose and the risk of hypertension in first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes. Hypertens Res 2015; 38: 349–354.

Adler AI, Stratton IM, Neil HA, Yudkin JS, Matthews DR, Cull CA, Wright AD, Turner RC, Holman RR . Association of systolic blood pressure with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 36): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000; 321: 412–419.

Stratton IM, Cull CA, Adler AI, Matthews DR, Neil HA, Holman RR . Additive effects of glycaemia and blood pressure exposure on risk of complications in type 2 diabetes: a prospective observational study (UKPDS 75). Diabetologia 2006; 49: 1761–1769.

Iso H, Imano H, Kitamura A, Sato S, Naito Y, Tanigawa T, Ohira T, Yamagishi K, Iida M, Shimamoto T . Type 2 diabetes and risk of non-embolic ischaemic stroke in Japanese men and women. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 2137–2144.

Kissela BM, Khoury J, Kleindorfer D, Woo D, Schneider A, Alwell K, Miller R, Ewing I, Moomaw CJ, Szaflarski JP, Gebel J, Shukla R, Broderick JP . Epidemiology of ischemic stroke in patients with diabetes: the greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 355–359.

Hu G, Sarti C, Jousilahti P, Peltonen M, Qiao Q, Antikainen R, Tuomilehto J . The impact of history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes at baseline on the incidence of stroke and stroke mortality. Stroke 2005; 36: 2538–2543.

Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Duncan BB, Gilbert AC, Pankow JS Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Investigators. Prediction of coronary heart disease in middle-aged adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 2777–2784.

Sone H, Tanaka S, Tanaka S, Iimuro S, Oida K, Yamasaki Y, Oikawa S, Ishibashi S, Katayama S, Ohashi Y, Akanuma Y, Yamada N Japan Diabetes Complications Study Group. Serum level of triglycerides is a potent risk factor comparable to LDL cholesterol for coronary heart disease in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: subanalysis of the Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 3448–3456.

Noguchi Y, Asayama K, Staessen JA, Inaba M, Ohkubo T, Hosaka M, Satoh M, Kamide K, Awata T, Katayama S, Imai Y,, HOMED-BP Study Group. Predictive power of home blood pressure and clinic blood pressure in hypertensive patients with impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1593–1602.

Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Kengne AP Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Patel A Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Barzi F Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Jamrozik K Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Lam TH Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Ueshima H Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Gu DF Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Suh I Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Woodward M . Systolic blood pressure, diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1205–1213.

Cederholm J, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Eliasson B, Zethelius B, Eeg-Olofsson K, Nilsson PM NDR. Blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetes: further findings from the Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR-BP II). J Hypertens 2012; 30: 2020–2030.

Henry P, Thomas F, Benetos A, Guize L . Impaired fasting glucose, blood pressure and cardiovascular disease mortality. Hypertension 2002; 40: 458–463.

Sehestedt T, Hansen TW, Li Y, Richart T, Boggia J, Kikuya M, Thijs L, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Casiglia E, Tikhonoff V, Malyutina S, Nikitin Y, Björklund-Bodegård K, Kuznetsova T, Ohkubo T, Lind L, Torp-Pedersen C, Jeppesen J, Ibsen H, Imai Y, Wang J, Sandoya E, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Staessen JA . Are blood pressure and diabetes additive or synergistic risk factors? Outcome in 8494 subjects randomly recruited from 10 populations. Hypertens Res 2011; 34: 714–721.

Alderman MH, Cohen H, Madhavan S . Diabetes and cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients. Hypertension 1999; 33: 1130–1134.

Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D . Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care 1993; 16: 434–444.

Katayama S, Moriya T, Tanaka S, Tanaka S, Yajima Y, Sone H, Iimuro S, Ohashi Y, Akanuma Y, Yamada N,, Japan Diabetes Complications Study Group. Low transition rate from normo- and low microalbuminuria to proteinuria in Japanese type 2 diabetic individuals: the Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS). Diabetologia 2011; 54: 1025–1031.

Takao T, Matsuyama Y, Suka M, Yanagisawa H, Kikuchi M, Kawazu S . Time-to-effect relationships between systolic blood pressure and the risks of nephropathy and retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Compl 2014; 28: 674–678.

De Cosmo S, Viazzi F, Piscitelli P, Giorda C, Ceriello A, Genovese S, Russo G, Guida P, Fioretto P, Pontremoli R,, AMD-Annals Study Group. Blood pressure status and the incidence of diabetic kidney disease in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes. J Hypertens 2016; 34: 2090–2098.

Kawasaki R, Tanaka S, Tanaka S, Yamamoto T, Sone H, Ohashi Y, Akanuma Y, Yamada N, Yamashita H,, Japan Diabetes Complications Study Group. Incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy in Japanese adults with type 2 diabetes: 8 year follow-up study of the Japan Diabetes Complications Study (JDCS). Diabetologia 2011; 54: 2288–2294.

Hammes HP, Welp R, Kempe HP, Wagner C, Siegel E, Holl RW DPV Initiative—German BMBF Competence Network Diabetes Mellitus. Risk factors for retinopathy and DME in type 2 diabetes—results from the German/Austrian DPV Database. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0132492.

Liu Y, Wang M, Morris AD, Doney AS, Leese GP, Pearson ER, Palmer CN . Glycemic exposure and blood pressure influencing progression and remission of diabetic retinopathy: a longitudinal cohort study in GoDARTS. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 3979–3984.

Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, Kowalski JW, Bek T, Chen SJ, Dekker JM, Fletcher A, Grauslund J, Haffner S, Hamman RF, Ikram MK, Kayama T, Klein BE, Klein R, Krishnaiah S, Mayurasakorn K, O'Hare JP, Orchard TJ, Porta M, Rema M, Roy MS, Sharma T, Shaw J, Taylor H, Tielsch JM, Varma R, Wang JJ, Wang N, West S, Xu L, Yasuda M, Zhang X, Mitchell P, Wong TY,, Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 556–564.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant-in-aid for Young Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (15H06913).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tatsumi, Y., Ohkubo, T. Hypertension with diabetes mellitus: significance from an epidemiological perspective for Japanese. Hypertens Res 40, 795–806 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2017.67

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2017.67

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypertension in diabetes

Pediatric Nephrology (2024)

-

Pretreatment body mass index affects achievement of target blood pressure with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

Relationship between obesity indicators and hypertension–diabetes comorbidity in an elderly population: a retrospective cohort study

BMC Geriatrics (2023)

-

The association of ideal cardiovascular health metrics and incident hypertension among an urban population of Iran: a decade follow-up in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study

Journal of Human Hypertension (2023)

-

Recent understandings about hypertension management in type 2 diabetes: What are the roles of SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist, and finerenone?

Hypertension Research (2023)