Abstract

The S allele of the functional 5-HTTLPR polymorphism has previously been associated with reductions in memory function. Given the change in function of the serotonergic system in older adults, and the functional consequences of memory decline in this age group, further investigation into the impact of 5-HTTLPR in healthy older adults is required. This investigation examined the effect of 5-HTTLPR variants (S carriers versus L/L homozygotes) on verbal and visual episodic memory in 438 healthy older adults participating in the Tasmanian Healthy Brain Project (age range 50–79 years, M=60.35, s.d.=6.75). Direct effects of 5-HTTLPR on memory processes, in addition to indirect effects through interaction with age and gender, were assessed. Although no direct effects of 5-HTTLPR on memory processes were identified, our results indicated that gender significantly moderated the impact that 5-HTTLPR variants exerted on the relationship between age and verbal episodic memory function as assessed by the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test. No significant direct or indirect effects were identified in relation to visual memory performance. Overall, this investigation found evidence to suggest that 5-HTTLPR genotype affects the association of age and verbal episodic memory for males and females differently, with the predicted negative effect of S carriage present in males but not females. Such findings indicate a gender-dependent role for 5-HTTLPR in the verbal episodic memory system of healthy older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Serotonin is one of the primary neurotransmitters in the central nervous system that has a well-established association with cognitive function and performance.1 In humans, disruption to the serotonin system can cause impairments to learning and memory function, with most robust effects found for verbal episodic memory.2 In addition to reduced cortical thickness and brain matter integrity, normal ageing is associated with a decline in both central nervous system levels of serotonin3 and memory function.4 As ageing-related memory deficits can contribute to reduced quality of life, as well as often predict dementia onset and mortality,5 further investigation of cognitive associations with serotonin function is warranted.

A key biological regulator of serotonin function is the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT), which encodes a presynaptic membrane-bound protein responsible for the re-uptake of serotonin from the synaptic cleft.6 A common polymorphism within the 5-HTT promoter region, serotonin transporter-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) is considered to influence the efficiency of serotonin re-uptake by the presynaptic 5-HTT.7 This polymorphism results in two alleles that differ in length: short ‘S’ and long ‘L’, with the S allele associated with reduced transcription of 5-HTT, fewer 5-HTT sites, less binding potential and therefore potentially less modulation of serotonin at the synapse.7, 8 A positron emission tomography study also linked higher verbal memory performance with greater 5-HTT availability in the prefrontal and parietal cortices of ecstasy users.9

The S variant relative to the L variant of 5-HTTLPR has been associated with reduced grey matter in areas of the brain responsible for episodic memory, specifically in the hippocampus of rodents,10 and healthy young11 and older adults.12, 13 In addition, the S variant has been associated with reduced neural activity in the prefrontal cortex of healthy older adults during a source memory monitoring task.13 The S variant has also been associated with reduced performance on neuropsychological tests of visual episodic memory in healthy young adults,11 and measures of delayed recall14 and source memory monitoring13 in healthy older adults. However, investigations have also reported null15 or inverse16 effects, whereby the authors reported that S carriers demonstrated increased performance on a working memory task in younger adults. Taken together, the literature is inconsistent surrounding the independent effect of variation in 5-HTTLPR on memory function.

The discrepancy in findings related to the cognitive implications of variation in 5-HTTLPR genotype may be partly accounted for by the modulating effects of demographic variables such as age and gender on gene function. In accordance with ageing-related changes in brain structure, such as reduced cortical thickness and matter integrity, S carriers show an increased vulnerability to reduced serotonin availability in the central nervous system as a result of tryptophan depletion;17 in the case of declining serotonin availability as a consequence of advancing age,3 it follows that S carriers may experience increasing memory deficits as a consequence of ageing. The genetic architecture and functioning of the serotonin system also appears to differ for males and females;18, 19 for example, lower serotonin levels have been observed in females relative to males of similar ages,20 and depletion of central nervous system serotonin levels via acute tryptophan depletion in females has been associated with impaired verbal short-term memory performance in young adults.21 Evidence from younger adults indicates that S carriage is associated with reduced visual recall solely in females, with no influence of the polymorphism present in males.11 Further elucidation of the potential interacting effects of age and gender with 5-HTTLPR genotype may provide greater insight into the possible predictive capacity of 5-HTTLPR genotype for accelerated ageing-related memory decline.

To explore the impact of serotonin on memory function in the ageing brain, the aim of the present study was to examine the effect of a functional polymorphism of the 5-HTT gene (5-HTTLPR) on visual and verbal episodic memory performance, either independently or through interaction with age and gender, in healthy older adults. We tested two hypotheses. First, that carriage of an S allele is associated with reduced episodic memory performance when compared with L homozygotes, overall. Second, that gender would moderate the effect of 5-HTTLPR genotype on the association of age and memory performance; specifically, that female S carriers show a greater detrimental influence of age on memory performance relative to female L homozygotes and males with either genotype.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study sample consisted of 438 adults aged 50–79 years, who were predominately Caucasian. Participants were enrolled in the Tasmanian Healthy Brain Project (THBP), which is an ongoing longitudinal study examining the potential beneficial effects of later life tertiary education on cognitive reserve, age-related cognitive decline and dementia.22 As part of the enrolment process, participants with conditions that may be independently associated with cognitive impairment were excluded from participation (dementia; multiple sclerosis; prior head injury requiring hospitalization; epilepsy; cerebrovascular complications including stroke, aneurysm, transient ischaemic attacks; poorly controlled diabetes; poorly controlled hypertension or hypotension; other neurological disorders, for example, cerebral palsy or spina bifida; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; heart disease; partial or total blindness; deafness; current psychiatric diagnosis). Refer to Summers et al.22 for full detail on screening measures. Ethics approval was obtained from the Tasmanian Social Sciences Human Research Ethic Committee and all the participants provided consent for use of their DNA.

Materials

Annual cognitive assessment is part of the THBP protocol to assess core cognitive domains—see Summers et al.22 for full details of cognitive assessment battery and protocol. To ensure approximate match of genotype groups, information on age, gender, intelligence, previous years of education, depression and anxiety was collected, as these factors have been found to affect performance on the memory tests utilized in the current study.23 Age, gender and years of prior education were collected during participants’ baseline assessments through the use of a self-report medical health status questionnaire. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale24 was used to assess the presence of depression and anxiety symptoms. The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading25 provided an estimate of premorbid full-scale intelligent quotient (IQ). Verbal episodic memory and learning was assessed using The Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT26). The RAVLT consists of a 15-item word-learning list that assesses verbal learning and recall across successive trials. Performance on the recall of the first RAVLT trial (Trial 1 recall), delayed recall (recalling list A after the presentation of an interference list) and performance over the five recall trials (RAVLT total) were included in the analyses. Visual episodic memory was assessed using the Paired Associates Learning (PAL27) test. Specifically, the current study analysed the accuracy of visual learning performance by the mean number of errors made on the PAL six shapes trial. The Rey Complex Figure Test26 was used to assess visual delayed recall. These memory measures have established reliability and validity for detecting memory impairment in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease.26, 28

Genotyping

Extraction and purification of DNA was performed following standard methods using saliva samples collected from participants (DNA Genotek, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012). The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism was identified using an established polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method.29 The PCR mixture contained the forward primer (stpr5, 5′-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC-3′) and reverse primer (stpr3, 5′-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC-3′), which yielded 484-bp (short) and 527-bp (long) fragments. Nine microlitres of the PCR mixture was added with 1 μl of DNA from the extracted and purified saliva sample in a 96-well plate. One well contained 1 μl of DEPC water in replacement of DNA, therefore acting as a no template control. After running samples through PCR, the products were separated using 3% agarose gel. All the samples were genotyped in duplicate to ensure accuracy.

Procedure

All neuropsychological tests were administered in standard conditions by a trained examiner, following THBP protocol.22

Data analysis

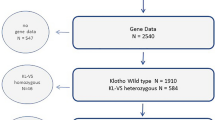

5-HTTLPR genotype was analysed in two groups by combining S/S and S/L genotypes to represent S carriers, and compared against L homozygous genotypes. Before the main analyses, a series of one-way analyses of variance were conducted to examine differences between genotype × gender groups on screening and demographic variables (age, years of prior education, intelligence, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety score and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale depression score). A chi-square goodness-of-fit test was also conducted to confirm that genotype distribution aligned with the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Raw scores for outcome measures, with the exception of the PAL test, which underwent a Log 10 transformation to approximate a normal distribution, were used in all analyses to enable the specific examination of age and gender as predictor variables. The primary analyses used model 3 of the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Chicago, IL, USA)30 for moderated-moderation analyses to assess whether gender and 5-HTTLPR genotype moderated the relationship between age and memory performance across visual and verbal domains of episodic memory (Figure 1). PROCESS is a computational tool for path analysis-based moderation and mediation analysis that provides coefficient estimates for total, direct and indirect effects of variables using ordinary least squares regression.30 Significant interaction effects identified by PROCESS were further examined using simple regression analyses to determine the extent to which the interaction contributed to the overall model. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and an alpha value of 0.05.

Results

Participants

The sample had a mean age of 60.35 years (s.d.=6.75) and were predominantly female (68%). On average, the sample had a greater than high school education level (M=13.94 years of education, s.d.=2.71) and had an above average IQ according to the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (estimated IQ M=112.43, s.d.=5.69). Screening and demographic variables stratified by 5-HTTLPR genotype and gender groups are presented in Table 1. One-way analysis of variance revealed significant differences between experimental groups in years of prior education and Wechsler Test of Adult Reading est. IQ. Overall, L/L females had significantly fewer years of education than the other three experimental groups. For Wechsler Test of Adult Reading est. IQ, male S carriers performed significantly worse than the other three experimental groups. A chi-square goodness-of-fit analysis demonstrated the distribution of the 5-HTTLPR genotype (χ2(2, N=438)=0.01, P=0.51) did not deviate significantly from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, and aligned with frequencies observed for other Caucasian samples.29, 30 Descriptive data for all outcome variables are presented in Table 2.

Verbal episodic memory performance

PROCESS model 3 was used to fit linear regression models to RAVLT outcome measures. With age entered as a predictor, 5-HTTLPR genotype and gender entered as moderators and total education (years) entered as a covariate, significant models were produced for all RAVLT outcome measures (Table 3): Trial 1 recall (F(8,425)=6.78, P<0.001, R2=0.09); delayed recall (F(8,426)=5.76, P<0.001, R2=0.11); RAVLT total (F(8,422)=13.12, P<0.001, R2=0.19). No significant independent associations of 5-HTTLPR genotype and RAVLT outcome scores were found. Age and gender had significant negative associations with immediate and total recall scores (P<0.01), indicating that advancing age and male gender were associated with lower performance. No significant two-way interaction terms were found, however, inclusion of the three-way interaction (5-HTTLPR genotype × age × gender) significantly improved model fit for RAVLT total score (ΔR2=0.008, P=0.04). The three-way interaction term did not significantly improve model fit for Trial 1 recall. To determine the basis for the three-way interaction, a further moderation analysis was conducted for 5-HTTLPR on the association of age and RAVLT total score for males and females separately (Figure 2). For males, the 5-HTTLPR interaction term was a significant predictor of RAVLT total score (t(132)=1.99, P=0.048), indicating that male S carriers displayed a significantly stronger relationship between age and episodic memory performance than male L/L homozygotes. Here, an analysis of simple slopes revealed that, while the association of age and RAVLT total in male S carriers significantly differed from zero (β=−0.55, 95% confidence interval, CI (−0.78, −0.31), t=−4.47, s.e.=0.12, P<0.001), male L/L did not show any significant relationship between the variables (β=−0.06, 95% CI (−0.47, 0.34), t=−0.31, s.e.=0.21, P=0.76). For females, the 5-HTTLPR interaction term did not significantly predict RAVLT total score (t(294)=−1.34, P=0.21), indicating that the association between age and RAVLT total score was similar for both female S carriers and female L/L homozygotes. The analysis of simple slopes reported that both female S carriers (β=−0.27, 95% CI (−0.73, −0.22), t=−3.68, s.e.=0.13, P<0.001) and female L/L homozygotes (β=−0.48, 95% CI (−0.42, −0.11), t=−3.36, s.e.=0.08, P<0.001) displayed negative relationships between age and RAVLT total score that were statistically different from zero.

Visual episodic memory performance

5-HTTLPR genotype, age and gender were regressed on visual episodic memory measures (Table 4), with significant models produced for both outcome variables: number of errors on PAL six shapes trial (F(8,429)=5.35, P<0.001, R2=0.10); RCFT delayed recall (F(8,428)=6.79, P<0.001, R2=0.12). No significant independent associations of 5-HTTLPR genotype were found for PAL test performance or RCFT performance. Age and gender were significantly and positively associated with PAL errors (P<0.01), indicating that advancing age and male gender were both independently associated with lower performance on the PAL test. Age and gender were both independently associated with RCFT performance (P<0.001); advancing age was associated with lower delayed recall performance, and male gender was associated with higher delayed recall performance. However, no interactions between predictors significantly contributed to the prediction of PAL error score or delayed recall on the RCFT.

Discussion

The current study was designed to investigate whether 5-HTTLPR genotype variants (S carrier versus L/L homozygote) were directly associated with visual and verbal episodic memory performance in a well-screened sample of healthy older adults. We also screened for indirect effects of the genetic variation, by examining whether 5-HTTLPR influenced the association of age and memory function, either independently or in combination with gender. Our first hypothesis, that carriage of an S allele is associated with an overall reduction in episodic memory performance when compared with L homozygotes, was not supported. In this investigation, 5-HTTLPR genotype was not significantly associated with assessed memory domains. Our second hypothesis, that gender would moderate the effect of 5-HTTLPR genotype on the association of age and episodic memory performance, was partially supported. In this study, we found evidence to suggest that 5-HTTLPR genotype affects the association of age and verbal learning performance, a component of the episodic memory system, for males and females differently. Here, we found the predicted negative effect of S carriage present in males but not females. Overall, these findings suggest that a gender-dependent role exists for 5-HTTLPR in the verbal episodic memory system of healthy older adults.

Although no direct influence of 5-HTTLPR genotype on episodic memory function was identified in the present study, the polymorphism showed a significant indirect association with verbal, but not visual, episodic memory function. This finding is partially consistent with the neuroanatomical dissociation of the verbal and visual system,31 as well as tryptophan depletion studies that suggest disruptions to the serotonergic system negatively affect verbal episodic memory functions more robustly than visual memory functions.2, 32 Findings are also consistent with MDMA research that shows blockage of uptake by 5-HTT results in impaired verbal memory performance.33 Another investigation by Zilles et al.34 found a selective effect of the 5-HTTLPR genotype on verbal working memory, but not visual memory performance, in a mixed sample of both healthy and psychiatric patients. In summary, our research adds further evidence that indicates a selective effect of the serotonergic system, mediated by 5-HTTLPR, on verbal memory performance.

The main finding from the present investigation was a gender-dependent influence of 5-HTTLPR polymorphism on the relationship between age and verbal learning. An analysis of simple slopes revealed that, for males, carriage of the S allele was associated with a stronger negative relationship between age and verbal memory function relative to L/L homozygotes. For males, each additional year of age was associated with a significant 0.53 point decrease in RAVLT total recall in S carriers, but a nonsignificant 0.11 point decrease in RAVLT total recall in L/L homozygotes. This effect is partially consistent with previous literature on healthy older adults, which has also reported associations of S carriage and reduced memory performance, specifically delayed recall on the RAVLT14 and memory monitoring tasks.13 Despite our results being consistent with these in regard to the S allele exerting a detrimental effect on function, the current findings differ in the memory domain that was affected by 5-HTTLPR. Furthermore, in our study, the effect of 5-HTTLPR was dependent on gender, with an influence of the polymorphism restricted to male participants. Similarly, but not confined to male gender, S carriage has been associated with deficits in verbal memory performance in individuals with experimentally reduced serotonergic system functioning (acute tryptophan depletion)17—a similar, but perhaps less severe, reduction to that which is observed with normal ageing.3

In contrast to males, the present study reported that, for females, both L/L and S carrier genotypes were associated with similar negative relationships between age and verbal memory performance. Specifically, for females, each additional year of age was associated with a significant 0.47 point decrease in RAVLT total recall in L/L homozygotes, and a significant 0.27 point decrease in RAVLT total recall in S carriers; these associations, however, did not statistically differ from one another. Price et al.11 also investigated the cognitive correlates of variation in 5-HTTLPR. Here, the authors identified that female S carriers performed worse on the California Verbal Learning Test-second edition when compared with L homozygotes. However, the authors investigated 5-HTTLPR effects within a sample of young adults (aged 18–25 years) and, as such, an antagonistic pleiotropic effect may partially account for differences in results. Furthermore, the hormone oestrogen has been demonstrated to interact with, and act on, a variety of receptors, including serotonin receptors.35 Oestrogen levels fluctuate across the female lifespan, with a marked decline in levels of the hormone occurring as a result of menopause.36 As the current study examined a healthy cohort of older aged adults with a minimum age of 50 years, the majority of females in the sample would have been postmenopausal, and therefore have reduced and relatively stable levels of oestrogen compared with the younger females that comprised the sample of Price et al.11 Consequently, it may be that a negative cognitive phenotype associated with the S allele in females occurs most commonly in younger ages, partly due to interactions with oestrogen.

Although other studies have reported that variation within the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism is directly associated with memory performance in older adults,13, 14 our data have failed to find support for this effect. Rather, our analysis from multiple components of both visual and verbal domains of episodic memory suggest an indirect gender-dependent effect of 5-HTTLPR on learning as a specific component of verbal episodic memory. Within the current study sample size of 438, we had 80% power to detect 2.17% variance in cognitive function. With enough power to detect a small moderation effect in all memory measures examined, the current findings suggest a differential effect of 5-HTTLPR variants exclusively on verbal episodic learning.

Methodological limitations of the present study should be considered when interpreting our results. First, the cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to assess developmental moderations of gender, age and 5-HTTLPR on memory performance. Specifically, such a design makes it difficult to determine whether age-related associations of gender, 5-HTTLPR and memory function represent ageing-related effects or are instead the result of cohort effects. Second, as the data set comprises primarily older adults participating in the intervention of tertiary education associated with the Tasmanian Healthy Brain Project, a self-selection bias may be present, whereby the sample comprises highly motivated and high-performing individuals. This limits the generalizability of our results to high-functioning individuals. Similarly, the generalizability is limited primarily to individuals of Caucasian ethnicity; due to identified frequency differences in allele distribution among different ethnic groups,19, 37 it is important that this is examined in future studies as an additional moderator of the gender, 5-HTTLPR and age effect on neurocognition. Third, as is typical of candidate gene studies,15, 38 the effect size for the 5-HTTLPR × age × gender interaction was small, but it is unlikely that a single genetic polymorphism would have a large direct effect on cognitive phenotypes. Finally, the use of a replication cohort would be a significant strength to ensure that findings are not the result of methodological biases, but this was not feasible in the current study and should be considered an important limitation.

Overall, research reliably reports that females tend to outperform males in tests of verbal memory.39 As a result, females may possess an advantage in this cognitive domain even before accounting for the findings of the present study, whereby male gender confers an additional vulnerability of verbal memory performance to advancing age. Other demographic differences between gender and 5-HTTLPR genotype groups may also have affected the results of the present study to some extent. In our sample, male S carriers had significantly lower premorbid est. IQ relative to male L/L homozygotes and females, overall. As reported, this male S carrier group showed a unique detrimental effect of age on verbal learning; consequently, speculation regarding the influence of this difference on the main result is warranted. Typically, individuals with a higher est. IQ tend to score better on tests of memory function.40 However, this is unlikely to account for the interaction of 5-HTTLPR and age that was observed in males. In this regard, although IQ has been demonstrated to modify risk of neuropathology-associated cognitive impairment,41 it is unlikely to affect the rate of ageing-related memory decline in healthy individuals.42 Accordingly, it is doubtful that the differences in est. IQ of experimental groups account for any of the observed variation in ageing-related memory performance.

The current results provide further evidence to suggest the S allele of the 5-HTTLPR genotype is disadvantageous. However, it may only lead to poorer neurocognitive outcomes in males, specifically for verbal learning abilities. These results, in combination with other findings on the cognitive consequences of genetic variations in single polymorphisms, may have useful implications for tailoring interventions that aim to reduce cognitive decline. This finding, in addition to other recent cross-sectional effects of COMT, APOE and BDNF on older adult cognition that have been reported in the Tasmanian Healthy Brain Project,43, 44 will be followed up in future longitudinal analyses of ageing-related cognitive change. It is likely that, to observe a polymorphism-related influence on adult cognitive function that is of a moderate effect size, concurrent consideration and analysis of multiple candidate gene variants is required.

References

Meneses A, Liy-Salmeron G . Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci 2012; 23: 543–553.

Mendelsohn D, Riedel WJ, Sambeth A . Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on memory, attention and executive functions: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009; 33: 926–952.

Rodriguez JJ, Noristani HN, Verkhratsky A . The serotonergic system in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol 2012; 99: 15–41.

Glisky EL . Changes in cognitive function in human ageing. In: Riddle DR (ed). Brain Ageing: Models, Methods and Mechanisms. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007.

Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 427–434.

Greenberg BD, Tolliver TJ, Huang SJ, Li Q, Bengel D, Murphy DL . Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter region affects serotonin uptake in human blood platelets. Am J Med Genet 1999; 88: 83–87.

Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 1996; 274: 1527–1531.

Heinz A, Jones DW, Mazzanti C, Goldman D, Ragan P, Hommer D et al. A relationship between serotonin transporter genotype and in vivo protein expression and alcohol neurotoxicity. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 47: 643–649.

McCann UD, Szabo Z, Vranesic M, Palermo M, Mathews WB, Ravert HT et al. Positron emission tomographic studies of brain dopamine and serotonin transporters in abstinent (+/-)3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”) users: relationship to cognitive performance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008; 3: 439–450.

Olivier JDA, Jans LAW, Blokland A, Broers NJ, Homberg JR, Ellenbroek BA et al. Serotonin transporter deficiency in rats contributes to impaired object memory. Genes Brain Behav 2009; 8: 829–834.

Price JS, Strong J, Eliassen J, McQueeny T, Miller M, Padula CB et al. Serotonin transporter gene moderates associations between mood, memory and hippocampal volume. Behav Brain Res 2013; 242: 158–165.

Frodl T, Koutsouleris N, Bottlender R, Born C, Jager M, Morgenthaler M et al. Reduced gray matter brain volumes are associated with variants of the serotonin transporter gene in major depression. Mol Psychiatry 2008; 12: 1093–1101.

Pacheco J, Beevers CG, McGeary JE, Schnyer DM . Memory monitoring performance and PFC activity are associated with 5-HTTLPR genotype in older adults. Neuropsychologia 2012; 50: 2257–2270.

O'Hara R, Schroder CM, Mahadevan R, Schatzberg AF, Lindley S, Fox S et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphism, memory and hippocampal volume in the elderly: association and interaction with cortisol. Mol Psychiatry 2007; 12: 544–555.

Payton A, Gibbons L, Davidson Y, Ollier W, Rabbitt P, Worthington J et al. Influence of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms on cognitive decline and cognitive abilities in a nondemented elderly population. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10: 1133–1139.

Enge S, Fleischhauer M, Lesch K-P, Reif A, Strobel A . Serotonergic modulation in executive functioning: linking genetic variations to working memory performance. Neuropsychologia 2011; 49: 3776–3785.

Roiser JP, Müller U, Clark L, Sahakian BJ . The effects of acute tryptophan depletion and serotonin transporter polymorphism on emotional processing in memory and attention. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 10: 449–461.

Weiss LA, Abney M, Cook EH, Ober C . Sex-specific genetic architecture of whole blood serotonin levels. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 33–41.

Williams RB, Marchuk DA, Gadde KM, Barefoot JC, Grichnik K, Helms MJ et al. Serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and central nervous system serotonin function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28: 533–541.

Nishizawa S, Benkelfat C, Young SN, Leyton M, Mzengeza S, de Montigny C et al. Differences between males and females in rates of serotonin synthesis in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94: 5308–5313.

Helmbold K, Bubenzer S, Dahmen B, Eisert A, Gaber TJ, Habel U et al. Influence of acute tryptophan depletion on verbal declarative episodic memory in young adult females. Amino Acids 2013; 45: 1207–1219.

Summers MJ, Saunders NLJ, Valenzuela MJ, Summers JJ, Ritchie K, Robinson A et al. The Tasmanian Healthy Brain Project (THBP): a prospective longitudinal examination of the effect of university-level education in older adults in preventing age-related cognitive decline and reducing the risk of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2013; 25: 1145–1155.

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, Tranel D . Neuropsychological Assessment, 5th edn. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP . The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370.

The Psychological Corporation Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). Harcourt Assessment: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2001.

Strauss E, Sherman E, Spreen O . A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms and Commentary, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

Cambridge Cognition Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Assessment Battery, 3rd edn. Cambridge Cognition: Cambridge, UK, 2004.

Fray P, Robbins T, Sahakian B . Neuropsychiatric applications of CANTAB. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 11: 329–336.

Taylor SE, Way BM, Welch WT, Hilmert CJ, Lehman BJ, Eisenberger NI . Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 60: 671–676.

Hayes AF . Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

Baddeley A . Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003; 4: 829–839.

Sambeth A, Blokland A, Harmer CJ, Kilkens TOC, Nathan PJ, Porter RJ et al. Sex differences in the effect of acute tryptophan depletion on declarative episodic memory: a pooled analysis of nine studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2007; 31: 516–529.

Wright NE, Strong JA, Gilbart ER, Shollenbarger SG, Lisdahl KM . 5-HTTLPR genotype moderates the effects of past ecstasy use on verbal memory performance in adolescent and emerging adults: a pilot study. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0134708.

Zilles D, Meyer J, Schneider-Axmann T, Ekawardhani S, Gruber E, Falkai P et al. Genetic polymorphisms of 5-HTT and DAT but not COMT differentially affect verbal and visuospatial working memory functioning. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012; 262: 667–676.

Barth C, Villringer A, Sacher J . Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. Front Neurosci 2015; 9: 37.

Hall G, Phillips TJ . Estrogen and skin: the effects of estrogen, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 53: 555–568.

Mannelli P, Patkar AA, Peindl K, Tharwani H, Gopalakrishnan R, Hill KP et al. Polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene and moderators of prolactin response to meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in African-American cocaine abusers and controls. Psychiatry Res 2006; 144: 99–108.

Weiss EM, Schulter G, Fink A, Reiser EM, Mittenecker E, Niederstätter H et al. Influences of COMT and 5-HTTLPR polymorphisms on cognitive flexibility in healthy women: inhibition of prepotent responses and memory updating. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e85506.

Sundermann EE, Maki PM, Rubin LH, Lipton RB, Landau S, Biegon A et al. Female advantage in verbal memory: evidence of sex-specific cognitive reserve. Neurology 2016; 8 7: 1916–1924.

Mohn C, Sundet K, Rund BR . The relationship between IQ and performance on the MATRICS consensus cognitive battery. Schizophr Res Cogn 2014; 1: 96–100.

Armstrong MJ, Naglie G, Duff-Canning S, Meaney C, Gill D, Eslinger PJ et al. Roles of education and IQ in cognitive reserve in Parkinson's disease-mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2012; 2: 343–352.

Zahodne LB, Glymour MM, Sparks C, Bontempo D, Dixon RA, MacDonald SWS et al. Education does not slow cognitive decline with aging: 12-year evidence from the victoria longitudinal study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2011; 17: 1039–1046.

Stuart K, Summers MJ, Valenzuela MJ, Vickers JC . BDNF and COMT polymorphisms have a limited association with episodic memory performance or engagement in complex cognitive activity in healthy older adults. Neurobiol Learn Mem 2014; 110: 1–7.

Ward DD, Summers MJ, Saunders NL, Janssen P, Stuart KE, Vickers JC . APOE and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms combine to influence episodic memory function in older adults. Behav Brain Res 2014; 271: 309–315.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Project Grant (No: 1003645 and 1108794) and the J.O. and J.R. Wicking Trust (Equity Trustees).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MJS reports personal fees from Eli Lilly (Australia), grants from Novotech, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Imlach, AR., Ward, D., Vickers, J. et al. Association between the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and verbal learning in older adults is moderated by gender. Transl Psychiatry 7, e1144 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.107

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.107