Abstract

Genetic models for polyploid crop adaptation provide important information relevant for future breeding prospects. A well-suited model is Brassica napus, a recent allopolyploid closely related to Arabidopsis thaliana. Flowering time is a major adaptation trait determining life cycle synchronization with the environment. Here we unravel natural genetic variation in B. napus flowering time regulators and investigate associations with evolutionary diversification into different life cycle morphotypes. Deep sequencing of 35 flowering regulators was performed in 280 diverse B. napus genotypes. High sequencing depth enabled high-quality calling of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertion-deletions (InDels) and copy number variants (CNVs). By combining these data with genotyping data from the Brassica 60 K Illumina® Infinium SNP array, we performed a genome-wide marker distribution analysis across the 4 ecogeographical morphotypes. Twelve haplotypes, including Bna.FLC.A10, Bna.VIN3.A02 and the Bna.FT promoter on C02_random, were diagnostic for the diversification of winter and spring types. The subspecies split between oilseed/kale (B. napus ssp. napus) and swedes/rutabagas (B. napus ssp. napobrassica) was defined by 13 haplotypes, including genomic rearrangements encompassing copies of Bna.FLC, Bna.PHYA and Bna.GA3ox1. De novo variation in copies of important flowering-time genes in B. napus arose during allopolyploidisation, enabling sub-functionalisation that allowed different morphotypes to appropriately fine-tune their lifecycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyploid crops like wheat, potato, oats and rapeseed have been enormously successful as field crops because of their huge adaptation potential. Indeed, the fact that all flowering plants derive from ancient or recent polyploidisation events1,2 points to an enormous evolutionary advantage associated with polyploidy. On the other hand, most polyploid events do not lead to a successful establishment of a new species3. Understanding how polyploids achieve adaptive potential has important implication for breeding in the context of environmental change.

On the other hand, the complexity of polyploid genomes has considerably restricted large-scale genetic studies of polyploid species4,5,6, so broad conclusions are often drawn based on diploid model plants like Arabidopsis thaliana. The polyploid crop most closely related to A. thaliana is rapeseed (Brassica napus), making it an excellent system to transfer information from the model to the crop. Despite its very recent origin and strong allopolyploidisation bottleneck6, rapeseed can be grown from boreal to subtropical and semi-arid areas, a result of strong differentiation into distinctly different morphotypes7.

The morphotype with highest seed yields is the biannual winter oilseed type8. The prerequisites for this lifecycle are winter hardiness for winter survival, along with vernalisation requirement to avoid pre-winter flowering7. In subtropical areas, cultivation of semi-winter types that can be vernalised in warmer temperatures is possible7. Boreal or semi-arid regions have periods of low plant survival rates, either due to strong winter freezing or extreme heat stress. In these regions, annual spring types are prominent. These are neither winter-hardy nor vernalisation-dependent, and the short growing season strongly limits yield potential. B. napus can also be grown as beet-like forms, known as swedes or rutabagas, which form a different subspecies (ssp. napobrassica)7. Swedes are generally of winter type, however have limited winter-hardiness and require extended vernalisation to flower (Fig. 1). No wild-types of B. napus are known, hence the species is assumed to have arisen in cultivation7, with at least one origin believed to be as recent as a few hundred years ago9. The different cultivated forms are bred in separate breeding pools, with introgression between morphotypes only in cases of extreme introgression benefit. However, this necessitates tedious backcrossing programs to restore the required ecogeographic adaptation characters10. Knowledge of the factors determining lifecycle traits like vernalisation requirement and flowering time is crucial for successful exchange of genetic material between B. napus gene pools10.

Although the mechanisms of vernalisation have been studied in depth in Arabidopsis, specific winter or spring alleles were not yet defined for B. napus. The predominant assumption is that the underlying genetic mechanisms are identical or very similar across crucifer species. The allopolyploid B. napus carries two almost intact subgenomes from the ancestors Brassica rapa (A subgenome donor) and Brassica oleracea (C subgenome donor). Both ancestral subgenomes arose from a common, hexaploid ancestor, raising the theoretical copy number of Arabidopsis gene homologs to six. Due to post-polyploidisation genome reduction, the average gene copy number is 4.411, whereby considerable variation has been observed among different gene families, with copy number ranging from 1 to 1212. Homology-driven chromosome rearrangements during allopolyploidisation are a key driver of such variation6,12. Copy number variations (CNVs) have been found to impart large phenotypic influence in several plant species like Arabidopsis13, wheat14, potato15 and maize16, but also in domestic animals17 and humans18.

In Arabidopsis, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) is the major repressor for the activity of the central flowering transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT)19. This gene cannot be expressed before FLC protein levels drop19, however when this occurs FT can be activated by the photoperiod pathway via the transcription factor CONSTANS (CO)20. Downregulation of FLC takes place at the transcriptional level. The FLC chromatin is modified and rearranged in order to stabilize a new inactive form21,22. Different mechanisms are involved in the structural regulation of FLC gene activity, including both autonomous regulators and the vernalisation pathway22,23. Three different mechanisms may exist for the breakdown of vernalisation requirement: (i) alteration of FLC regulating factors like FRIGIDA (FRI); (ii) alteration of FLC gene sequence or activity; (iii) alteration of FLC binding sites or FT promoter sequences. Arabidopsis annuals and biannuals have been found to differ either in FRI or in FLC24, indicating that the Arabidopsis winter-spring split is governed by the first two levels of regulation. As a consequence, research on B. napus vernalisation has been heavily focused on investigating FLC homologs25,26,27. Indeed, a number of QTL studies in different mapping populations have suggested FLC loci as candidates for flowering time in B. napus, including populations without vernalisation requirement28,29,30,31,32. Moreover, it has been reported that a transposon insertion in the first intron of Bna.FLC.A10 is associated with the vernalisation requirement of winter-type rapeseed27.

The aim of the present work was therefore the definition of morphotype-specific alleles or haplotypes that might further our understanding of vernalisation control in a complex allopolyploid, and simultaneously allow breeders to successfully select for desirable lifecycle traits. By comparing results of vernalisation experiments with data from genome-wide marker distribution analysis, targeted deep-sequencing of essential flowering time regulators and the FT promoter, and coverage analysis to estimate CNV, we provide novel insights that reveal the complexity of post-polyploidisation morphological diversification in an important crop species.

Material and methods

Plant material and phenotyping

A panel of 280 genetically diverse B. napus inbred lines (selfed for 5 or more generations) was grown in Giessen, Germany (50° 35′ N, 8° 40′ E) in 2012. The plant material was part of the ERANET-ASSYST B. napus diversity set that has been described previously33,34. Winter-type rapeseed and swede accessions were grown in autumn-sown trials, whereas spring-type and semi-winter accessions were grown in spring-sown trials. Plots were sown in a completely randomized block design with a harvest plot size of 3 × 1.25 m in a single replicate (containing around 200 plants).

In a separate experiment, a selection of 33 genotypes from the same set was grown in the greenhouse under semi-controlled conditions (20 °C). These genotypes were selected to represent spring, winter and swede material with different CNV patterns for Bna.FLC. Twenty seeds were sown in vermiculite, before being transplanted after one week into plates in soil, with 5 replicates per treatment. Four weeks after planting, these plants were either transferred to a climate chamber for vernalisation at 4 °C and short-day conditions for 6 weeks (mild vernalisation) or 12 weeks (strong vernalisation), or kept in the greenhouse (no vernalisation). Begin of flowering (BBCH 61) was tracked daily for every single plant.

DNA isolation

Leaf material for genomic DNA extraction was harvested in spring 2012 from the field trial in Giessen, Germany. Pooled leaf samples were taken from at least 5 different plants per genotype, immediately shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −20 °C until extraction. Leaf material was ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. DNA was extracted using a common CTAB protocol modified from Doyle and Doyle (1990) as described earlier12. DNA concentration was determined using a Qubit fluorometer and the Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quantity and purity was further checked on 0.5% agarose gel (3 V/cm, 0.5xTBE, 120 min).

Selection of target genes

As described previously12, a set of 29 A. thaliana flowering time genes was selected to cover the entire genetic network controlling flowering time, including circadian clock regulators (CYCLING DOF FACTOR 1 (CDF1), EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3), GIGANTEA (GI) and ZEITLUPE (ZTL)), the input pathways for vernalisation (EARLY FLOWERING 7 (ELF7), EARLY FLOWERING IN SHORT DAYS (EFS), FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), FRIGIDA (FRI), SHORT VEGTATIVE PHASE (SVP), SUPPRESSOR OF FRIGIDA 4 (SUF4), TERMINAL FLOWER 2 (TFL2), VERNALISATION 2 (VRN2), VERNALISATION INSENSITIVE 3 (VIN3)), photoperiod sensitivity (CONSTANS (CO), CRYPTOCHROME 2 (CRY2), PHYTOCHROME A (PHYA), PHYTOCHROME B (PHYB)) and gibberellin (GIBBERELLIN-3-OXIDASE 1 (GA3ox1)), along with downstream signal transducers (AGAMOUS-LIKE 24 (AGL24), APETALA 1 (AP1), CAULIFLOWER (CAL), FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD), FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), FRUITFUL (FUL), LEAFY (LFY), SQUAMOSA PROMOTOR PROTEIN LIKE 3 (SPL3), SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1), TEMPRANILLO 1 (TEM1), TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1)). On top, we also included CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSISTED 1 (CCA1), FLAGELLIN-SENSITIVE 2 (FLS2), GLYCIN-RICH PROTEIN 7 (GRP7), GLYCIN-RICH PROTEIN 8 (GRP8), GORDITA (GORD) and SENSITIVITY TO RED LIGHT REDUCED 1 (SRR1).

A full list of gene names and putative functions is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Bait development

In order to perform target enrichment, complementary sequences of 120 nt length were first developed for each target region. A group of 120mer oligonucleotide sequences covering a certain target region is hereinafter referred to as a bait group for that target region, while collectively all bait groups are referred to as the bait group pool. In the present study the bait group pool for the sequence capture, developed mainly using gene sequences from B. rapa or B. oleracea12, was modified in order to improve specificity. Enriched regions captured in our previous study12 were classified into target regions and non-target regions. The bait pool was then blasted against target and non-target regions with an E-value cut-off of 10−10. Baits which had excessive non-target hits were manually removed. This was the case for bait groups on FT, FUL and PHYA. For some bait groups (AP1, CO, SOC1), too many baits (>30%) were deleted. In these cases, bait groups were created using a pre-publication draft (version 4.0) of the B. napus ‘Darmor-Bzh’ reference genome sequence assembly, which was kindly made available prior to public release by INRA, France, Unité de Recherche en Génomique Végétale6, using the Agilent Genomic Workbench program SureDesign (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). These replaced the corresponding bait groups developed previously using B. rapa or B. oleracea. Bait groups were created using the ‘Bait Tiling’ tool. The parameters were set as follows: Sequencing Technology: ‘Illumina’, Sequencing Protocol: ‘Paired-End long Read (75 bp+)’, ‘Use Optimized Parameters (Bait length 120, Tiling Frequency 1x)’, Avoid Overlap: ‘20’, ‘User defined genome’, ‘Avoid Standard Repeat Masked Regions’. Baits for genes on the minus-strand were developed in sense, while baits on the plus-strand were developed in antisense.

In total, 63 bait groups were created for B. rapa copies of the target genes, 71 bait groups for B. oleracea copies and 24 bait groups for B. napus copies.

Sequence capture and sequencing

Custom bait production was carried out by Agilent Technologies (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the output oligonucleotide sequences from eArrayXD. Sequence capture was performed using the SureSelectXT 1 kb–499 kb Custom Kit (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting TruSeq DNA library (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer at the Max Planck Institute for Breeding Research (Cologne, Germany) in 100 bp single-read mode.

Sequence data analysis

Quality control of the raw sequencing data was performed using FASTQC. Reads were mapped onto version 4.1 of the B. napus ‘Darmor-Bzh’ reference genome sequence assembly6. Mapping was performed using the SOAPaligner algorithm35, with default settings and the option r = 0 to extract uniquely aligned reads. Removal of duplicates, sorting and indexing was carried out with samtools version 0.1.1936. Alignments were visualised using the IGV browser version 2.3.1237. Enriched regions and coverage differences were calculated using the bedtools software with multiBamCov38. Calling of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was performed with the algorithm mpileup in the samtools toolkit. SNP and InDel annotation was performed using CooVar39. Target regions were defined using the gene annotation list from the B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ v4.1 reference genome6 and BLAST position results of the bait pool (E-value cut-off 10−100) on the mapping reference, and used to calculate the fraction of target covered. For InDel calling, a separate mapping using Bowtie240 was performed, as described previously41. Removal of duplicates, sorting and indexing was carried out with samtools version 0.1.19. An initial InDel calling was performed using samtools mpileup, and realignment of reads around InDels was performed using GATK RealignerTargetCreator, version 3.1.142. A final InDel calling was then performed as described above. InDels were filtered for a minimum mapping quality of 30 and a read depth of 10 or more using vcftools43.

Read coverage for each captured region was normalised as follows: normalised coverage = (number of reads per region*total length of genome)/(total number of aligned reads per genotype*average read length). Copy number variation (CNV) in a given target region was assumed if the ratio of normalised coverage(genotype)/normalised coverage(all genotypes) was smaller than 0.5 or higher than 1.5, respectively.

Sequencing data for 3 genotypes from a former experiment (Silona, Campino, Magres Pajberg)12 were analysed separately with the same pipeline to allow inclusion in the marker distribution analysis.

SNP genotyping and pre-processing

The 283 accessions were genotyped using the Brassica 60 K Illumina® Infinium SNP array by TraitGenetics GmbH (Gatersleben, Germany). We used the SNP positions as published in44. Heterozygous calls were treated as missing values. Moreover, we used the deep sequencing data to include all confidently called SNPs in biallelic state which lay in the analysed regions. Confidently called InDels were included by coding reference alleles as AA, insertions as CC, deletions as TT and heterozygous calls as missing values. The SNP matrix from the SNP array and the SNP and InDel data from deep sequencing were combined to one single marker file and sorted by position. The subsequent marker set contained 43733 markers. After pre-processing the marker set for non-missing marker values >0.9, minor allele frequency >0.01 and individuals (genotypes) with non-missing individual markers >0.8, we retained 33944 unique SNP markers and a population of 271 individuals for marker distribution analysis. Data pre-processing was performed with R (version 3.1.0) using the package GenABEL45.

Population structure

Population structure analysis and visualization were performed in R (version 3.1.0) using the package SelectionTools (http://fb09-pg-s207.agrar.uni-giessen.de/~frisch-m/), which applies principal component analysis based on genetic distances calculated according to the euclidean modified Rodger’s distance method. The most likely number of population subclusters was determined to be 3 by plotting the within-cluster sum of squares against the possible number of clusters, ranging from 1 to 15. K-means clustering was then performed in R using SelectionTools.

Marker distribution analysis

For every marker, we counted the allele frequency of the alternative allele in each morphotype pool. The ratio between the frequency of the allele in the winter pool (winter + swedes) and the spring pool (semi-winter + spring) was used to assign the allele as a winter or spring allele. If the ratio was <1, the alternative allele was denoted spring (s), if it was >1, the alternative allele was denoted winter (w). We then first tested if the marker would be suitable to explain a morphotype split, by comparing the observed distribution of w alleles in the winter pool (without swedes) and s alleles in the spring pool (without semi-winter) with the expected distribution (139/114), using a χ2 test. Only markers which did not show significant deviation from this distribution (p-value > 0.1) were considered in the next step. In the next step, we tested the distribution against random distribution between the pools, by comparing the observed distribution of w alleles in winter/s alleles in spring/s alleles in winter/w alleles in spring against the expected random distribution of 69.5/57/69.5/57. We then considered the top 0.1% of −log(p-value) as split markers. The same was done for the swede and non-swede material.

Results

Deep sequencing and variant calling

We defined regions as genetic regions which were covered with a mean coverage in the population of at least 10. In total, we analyzed 1184 regions, of which 637 regions were annotated as genes. Of these, 184 corresponded to the intended target genes. Two target genes copies for VERNALISATION INSENSITIVE 3 (VIN3) (Bna.VIN3.A01 and Bna.VIN3.C01) had insufficient coverage for this analysis and were not considered. Among the non-genic regions, we found 33 regions giving a BLAST hit to the FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) promoter. A further 12 regions were identified as pseudogenes of the target genes. Those regions which were assigned to one of those classes (target genes, target pseudogenes and FT promoter) were summarized as target regions. A gene group is defined as all copies of a specific gene.

We called and annotated 13053 SNPs, of which 4806 were located in the target regions. InDel calling revealed a total of 1894 InDels, with 506 in the target regions. Only 25 InDels were frameshifts, amino acid insertions or splice variants. All gene groups showed potentially functional variation, i.e. at least one copy of the gene group carried either a non-synonymous SNP, stop codon mutation, amino acid insertion, splice variant or frameshift InDel. Altogether, only 7 copies were completely conserved, while 16 copies carried only silent or synonymous variation. Interestingly, no functional variation was observed in two copies of Bna.FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) (on chromosomes A02/C02) and two copies of Bna.FT (also on chromosomes A02/C02), respectively. On the other hand, other copies of Bna.FLC (A03, A10) and Bna.FT (C06) carried a surprisingly large range of variation. Among the genes with frameshift variants were copies of Bna.FRIGIDA (FRI), Bna.PHYTOCHOME A (PHYA), Bna.EARLY FLOWERING IN SHORT DAYS (EFS), Bna.EARLY FLOWERING 7 (ELF7), Bna.PHYTOCHROM B (PHYB), Bna.VERNALISATION 2 (VRN2) and Bna.LEAFY (LFY) (Fig. 2). We also calculated copy number variation (CNV) based on read depth. No gene group was found without CNV, and only two lines were found which did not carry any CNV among the target copies. The distribution of SNPs, InDels and CNVs is shown in Fig. 2.

The chromosomal locations of the copies are given below the common Arabidopsis gene name (white background), with colors representing the respective type of sequence variation observed (see color code below each diagram). Upper panel: Silent SNPs are not indicated if synonymous or non-synonymous SNPs are present in the same copy, and synonymous SNPs are not indicated if non-synonymous SNPs are present in the same copy. Lower panel: Gene copies showing two different colors are deleted in some lines and duplicated in some others.

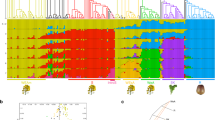

Population structure

Among the analysed population of 271 accessions, we had 139 winter type accessions, 7 semi-winter type accessions, 114 spring type accessions and 11 swedes. Analyzing this population with a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showed a strong population substructure, as the first principal component explained 24.1% of the variation, while further components explained 5.4, 2.5 and 2.1%, respectively (Fig. 3). The population falls into three main clusters: the first cluster contained 137 winter type accessions, the second one 93 spring type accessions and a semi-winter type accession, and the third and most diverse cluster contained 11 swedes, 6 semi-winter type accessions, 21 spring type accessions and 2 winter type accessions. We concluded that the winter material was genetically least diverse, while spring material was more diverse, followed by semi-winter and swede material. Overlap between winter and spring pools is minimal, while all other types show more overlap, although swedes are more distant from the winter and spring core clusters.

Marker distribution analysis

To analyse marker distribution on a genome-wide scale, we used SNP data from the Brassica 60 K Illumina® Infinium SNP array and combined it with data from deep sequencing (SNPs and InDels). In order to find the most indicative marker patterns for the differential flowering behaviour of winter and spring material, we analyzed the differential marker pattern between the different morphotypes using the χ2 test. We first defined “winter” and “spring” alleles by allele frequencies in the different morphotypes and assessed their distribution in both pools. First, we excluded all markers with non-suitable allele frequencies. We regard all markers as non-suitable if their minor allele frequency was too low to explain a population split. This was tested in a foregoing χ2 test (see Methods). The remaining markers were tested against random distribution in the respective morphotypes. The same was done for swedes against non-swede accessions. Choosing a cut-off which considers the top 0.1% of markers (-log[p-value] = 38.9 for winter/spring and 55.8 for swedes), we detected 12 regions on chromosomes A01, A02, A03, A07, A09, A10, C03, C06 and C09 for the winter-spring split (Fig. 4), and 13 regions on chromosomes A03, A04, A06, A09, C01, C08 and C09 for the swede split.

Analysis of split regions

We subsequently counted how many of the 12 winter-spring split regions have a clear winter or spring pattern in each genotype, i.e. the number of cases where every split marker in the haplotype corresponded to the winter or spring state (Table 1). The distribution of lines carrying clear winter and spring haplotypes is shown in Fig. 5. Mixed haplotypes were excluded here, as they account for less than 5% of the haplotypes. From this distribution, we concluded that characterizing these regions for their haplotype pattern is sufficient to distinguish winter from spring morphotypes, but not to distinguish semi-winter or swede morphotypes. The same analysis on 13 split regions identified for the swede vs. non-swede split revealed a more explicit distribution (Table and Fig. 6). Genotyping these loci is therefore sufficient to distinguish swede morphotypes from non-swedes.

In order to exclude candidates for the respective morphotype split, we specifically looked at the variant distributions from deep sequencing in our marker set. Because these derived from sequence data, a poorly fitting distribution excludes the sequence from being a major cause for this morphotype, as sequencing covers the total variation of a gene. This is not the case for data from the SNP array, as even genic SNPs are not always completely predictive for their neighbor SNP. For the winter-spring split, only 6 sequenced regions with a distribution comparable to the detected split markers could be found, among them Bna.VIN3.A02, Bna.FLC.A10 and the Bna.FT promoter on the non-assembled scaffolds of C02_random (Table 1). With the exception of Bna.FLC.A10 (R10P mutation), all those SNPs are either synonymous or located in an intron. For the non-swede vs. swede split, we found 17 sequenced regions carrying variants with an acceptable distribution, for example three copies of Bna.FLC, two copies of Bna.CO and a further copy of Bna.FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD) (Table 2).

Upstream of the gene Bna.FT on C02_random we found two regions, spanning 4622 and 4904 bp, respectively, which retrieved BLAST hits to the A02 or C02 copies of the Bna.FT promoter listed by NCBI. We therefore identified these sequences as the promoter of Bna.FT on C02_random. Both sequences contain a CArG box core motif, whereby the first sequence also contains 3 additional FLC binding sites known from A. thaliana46 and the second sequence contains 2 such FLC binding sites. No SNP is located in those motifs. We found that most (143 of 145) winter types are unchanged in both sequences or carry only minor changes, whereas most (71 of 116) of the spring population carried one of two distinctive haplotype patterns involving a SNP at position C02_random:980227 (Fig. 7). These patterns were shared by only two putative winter-type accessions, one of which is an exotic accession that may not need vernalisation, whereas the other is an accession which the vernalisation experiments revealed to have vernalisation-independent flowering (see below).

We furthermore compared the numbers of deletion and duplication events in the different morphotype pools. For the winter-spring split, we found no specific pattern for the total population. In contrast, we found several patterns of deletions and duplications which were almost exclusive to swedes, concerning split regions on A08, A09, A10, C08 and C09 (Table 3). The regions on A09/C08 (containing copies of Bna.PHYA and Bna.GIBBERELLIN 3 OXIDASE 1 (GA3ox1) and A10/C09 (containing copies of Bna.FLC) are homeologous to each other. Some of these regions, particularly those on C08, appear to involve larger homoeologous exchanges that probably affect not only the detected genes.

For the winter-spring split, we found 234 genes with flowering-related gene ontology terms within 1 Mb of one of the diagnostic split markers. Examples are shown in Table 4. In the 13 regions showing a split between swedes and non-swedes, we found 260 candidate genes within 1 Mb. In this analysis, several split markers lay directly in candidate genes covered by deep sequencing, for example Bna.VIN3, Bna.PHYA (2 copies), Bna.TEMPRANILLO1 (TEM1), Bna.ELF7, Bna.CONSTANS (CO), Bna.CO-like or Bna.CINNAMOYL COA REDUCTASE 1 (CCR1) (Table 5). Some of those markers were non-synonymous SNPs (in Bna.CCR1, Bna.TEM1, Bna.CO, Bna.CO-like), whereas others were either synonymous or located in introns or untranslated regions (UTRs).

Vernalisation trials

In order to test if the swede-specific pattern of Bna.FLC deletions and duplications would affect vernalisation dependency, we conducted a vernalisation trial with a reduced set of lines (11 lines each from the winter, spring and swede panels). These were selected to represent either lines without CNV in Bna.FLC (as a control), or lines which have alternative patterns of deletion and duplication in Bna.FLC. The plants were subjected to either 6 or 12 weeks of vernalisation, or were not vernalised. We then scored the time until opening of the first flower. We found that all spring lines and one winter line were vernalisation independent. The vernalisation-independent winter line was one of the two genotypes carrying a strongly divergent Bna.FT promoter on C02_random. All swedes and three winter lines were found to be strongly vernalisation dependent, meaning that no plants flowered after mild vernalisation. At the end of the experiment, one winter line and 8 swede lines did not flower at all, meaning that 12 weeks of vernalisation were not sufficient to induce flowering (Fig. 8).

The height of the bars represents the number of replications which could be phenotyped. Yellow indicates flowering plants, grey indicates non-flowering plants. The different treatments are framed in different colors, with green indicating no vernalisation, blue mild vernalisation (6 weeks) and red strong vernalisation (12 weeks).

For the spring types, we found that lines with altered Bna.FLC patterns flower significantly later than lines without such changes (Fig. 9). All the same, spring lines carrying a swede pattern in Bna.FLC were not vernalisation dependent, indicating that this pattern is not sufficient to induce vernalisation.

Discussion

Our study aimed at identifying genetic variants which are responsible for the separation of the different morphotype pools in B. napus. According to population structure analyses performed in this and other studies33,34,47, winter-type B. napus accessions tend to separate almost completely from other accessions, while some spring types along with semi-winter and swede material are more diverse. Here, we defined a total of 12 variant haplotypes which are diagnostic for the winter-spring split, and 13 variant haplotypes for the swede-non-swede split. Moreover, we found one winter type without vernalisation requirement that was nevertheless winter-hardy, and spring types with some degree of vernalisation responsiveness. Swedes were found to be extremely vernalisation dependent, with some variation among the accessions, presumably because swede forms have been bred to maintain their vegetative state for as long as possible. Vernalisation is a quantitative process48, so there is natural variation in responsive temperature range and vernalisation duration21,49,50,51. Markers for such life cycle traits are extremely important in order to introgress desirable traits between ecogeographical or morphotype gene pools, for example seed quality traits from spring to winter oilseed forms52 or resistance traits from swede to non-swede material53.

An R10P mutation in the MADS box domain of Bna.FLC.A10 was revealed as one candidate for the winter-spring split in B. napus, however our data shows that this mutation is neither the only candidate nor the best one. Neither the other Bna.FLC homologues, nor the detected copies of Bna.FRI, showed an appropriate variant distribution to explain the winter-spring split. Similar results were found for natural variation in flowering time for A. thaliana54,55. This excludes the possibility that genetic variation within Bna.FLC gene sequences, besides Bna.FLC.A10, are causal for vernalisation requirement, thus indicating that other Bna.FLC copies are either not responsible for vernalisation or there is variation in cis-regulatory elements. As shown by the vernalisation trials, spring-type plants without CNV in Bna.FLC copies flower earlier, indicating that Bna.FLC still plays a role in modulating flowering time in the absence of vernalisation requirement. Spring genotypes with a high Bna.FLC copy number showed accelerated flowering under vernalisation, indicating that they established weak vernalisation responsiveness. FLC is known to bind many other genes in A. thaliana46, and it also regulates other developmental processes like germination56, hence additional copies might be assumed to underlie strong selection. The differential degree of conservation between the copies suggests sub-functionalisation, whereby conserved Bna.FLC.A02 and Bna.FLC.C02 presumably retain more general roles, whereas Bna.FLC.A10 might be more specialized towards flowering regulation. Sub-functionalisation events are characteristic for the evolution of MADS box transcription factors57,58.

On the other hand, Bna.SRR1.A02, Bna.VIN3.A02, Bna.AGL71.A03, Bna.CCR1.A09_random and the Bna.FT promoter on C02_random represent further candidates for the morphotype split. SRR1 is a clock-associated gene found to regulate CO, FT and CYCLING DOF FACTOR 1 (CDF1) in A. thaliana59. Moreover, A. thaliana srr1 mutants have reduced levels of FLC and respond only weakly to vernalisation59. Similarly, Bna.VIN3.A02 represents a copy of another vernalisation candidate upstream of Bna.FLC54. In Arabidopsis, VIN3 is expressed during cold and associates to the PRC2 complex to downregulate FLC gene activity22,60. AGAMOUS-LIKE 71 (AGL71) is closely related to the flowering integrator SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1) and seems to be involved in gibberellin-dependent flowering pathways61. Its promoter contains a CArG box for FLC binding in A. thaliana62. CCR1 is a biosynthetic enzyme in lignin production and leaf development, which is known to regulate the concentration of the antioxidative compound ferulic acid63. This could be related to cold perception, as cold is partly perceived via the redox state64. Although all observed candidate SNPs are synonymous or silent, they may still have strong potential consequences for cis-regulatory elements, methylation, small RNA regulation and chromatin structure, and associated changes in the promoter. Moreover, alternative splicing was found to occur abundantly in resynthesized B. napus, also for copies of Bna.FLC65. On the other hand, we also cannot fully exclude that the observed effects are caused by linkage to additional genes in the neighbourhood of the investigated flowering-time regulators.

We also found patterns on the Bna.FT promoter on C02_random associating with the winter-spring split. Haplotype analysis showed that only two winter lines showed a strongly varying pattern, resembling most of the spring morphotypes. One of these was an exotic line, while the other was found to be vernalisation independent. This indicates that a functional promoter sequence for this gene is necessary to build up vernalisation requirement. A change in vernalisation requirement through variation in an FT promoter was already found in different Brassicas66, narrow-leafed lupine67 and litchi68. In A. thaliana, FLC was shown to bind to a CArG box located in the first intron of FT69, although in cereals the binding site lies in the promoter70. Indeed, the Bna.FT copy on C02_random contains a CArG box motif. It is possible that both the promoter and the intron are responsible for Bna.FLC binding. All the same, in both winter and spring types it has been reported66 that the A02 copy in B. napus is constitutively expressed and the C02 copy is completely silenced, whereas the copies on A07 and C06 appear to be specifically silenced in winter morphotypes but transcribed in spring morphotypes66. As our Bna.FT copy on C02_random corresponds to the C02 copy reported in the aforementioned study66, we assume that either there was a problem with the RT-PCR due to allelic variation, or the regulatory mechanism is more complex. However, in an independent transcriptome study we were unable to detect the constitutive expression of Bna.FT.A02, nor of any other Bna.FT copy, in winter-type B. napus before vernalisation (C. Obermeier, unpublished data).

Genomic rearrangements are common in B. napus6,41,71,72,73,74,75. They are particularly predominant in the first generations after allopolyploidisation72, but the process is ongoing and believed to have an important role in speciation76. Different studies found indications for genomic rearrangements between B. napus morphotypes6,12,29. In the present study we found CNVs concerning copies of Bna.FLC, Bna.PHYA and Bna.GA3ox1 to involve duplications in the A subgenome and corresponding homoeologous deletions in the C subgenome. This indicates replacement of the C-subgenome regions by the respective A-subgenome regions, a process known as homeologous non-reciprocal translocation (HNRT)77. A de novo HNRT will erase any sub-functionalisation which may have occurred prior to the rearrangement. Our data concur with the hypothesis27 that the Bna.FLC.A10 copy is most specifically involved in flowering regulation. A duplication in Bna.FLC.A10 would therefore increase vernalisation requirement. This hypothesis fits with the strong vernalisation requirement we observed in lines carrying this duplication. Differential expression of Bna.FLC in highly rearranged, resynthesized rapeseed was observed before26. All the same, this pattern can only be effective when the vernalisation system is functional, as two spring lines with the same pattern are not vernalisation dependent. One of these presumably has a defective Bna.FT promoter on C02_random, whereas neither of them carries the swede-specific Bna.VIN3.A03 marker.

Other genes affected by such HNRTs are Bna.PHYA and Bna.GA3ox1. PHYA is a red/far-red perceiving photoreceptor which has a stabilising role for CO under long days78. This might represent a necessary co-adaptation of the photoperiodic pathway due to the strong vernalisation requirement, as later flowering means that the day length is longer at the time of flowering. This assumption is underlined by the finding that a D94G mutation in a copy of Bna.CO-like is a candidate for the swede split. GA3ox1, a biosynthetic key gene involved in GA production, is regulated by PHYB and by feedback mechanisms of downstream pathways79. GA also affects other developmental processes like seed germination, hypocotyl elongation and fruit set79,80. Bna.GA3ox1 is therefore also a candidate for the swede morphotype, which is characterized by an enlarged hypocotyl and low seed-set. This might also apply to Bna.CCR1 as a candidate for the swede split. In Arabidopsis CCR1 is involved in lignin biosynthesis, leaf development regulation and regulation of the redox state63 (see above).

All swede lines share a silent mutation in Bna.VIN3.A03, which is not shared by any other line. Although the consequence of this mutation is unclear, Bna.VIN3 is a strong candidate for vernalisation requirement, particularly because another copy is a candidate for the winter-spring split (see above). Copies of VIN3 have previously been named as candidates for vernalisation requirement and flowering time in A. thaliana and B. napus54,81. In B. oleracea, it was found that BoVIN3 was upregulated much faster than A. thaliana VIN382, indicating that the expression is more sensitive to cold. Another upstream candidate for the strong vernalisation requirement is Bna.ELF7. ELF7 is involved in chromatin remodeling of FLC during vernalisation83. A further gene variant which was not found outside the swede population lay in Bna.TEM1. TEM1 encodes another repressor of FT, which competes with CO for the same genetic region to fulfill their function84. The variant is a non-synonymous T167R mutation that potentially affects binding to the UTR of FT. A further candidate, Bna.FD, possibly modulates FT protein effectiveness, as FD is a direct and essential interaction partner of FT in the shoot apex85.

These results represent an excellent base for further experiments to transfer morphotype features between B. napus genetic pools. Moreover, they also shed light on the evolution of major flowering time genes in the aftermath of allopolyploidisation, and their role in morphotype diversification and ecogeographical adaptation. We clearly demonstrate that different copies of important flowering regulators play different regulatory roles across the vernalisation and flowering pathways. The scarcity of non-synonymous mutations, along with the observed variation in the Bna.FT promoter, underline the importance of cis-regulatory mechanisms in flowering time regulation.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Schiessl, S. et al. Post-polyploidisation morphotype diversification associates with gene copy number variation. Sci. Rep. 7, 41845; doi: 10.1038/srep41845 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Adams, K. L. & Wendel, J. F. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr Opin Plant Bio 8, 135–141 (2005).

Soltis, P. S. & Soltis, D. E. The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60, 561–588 (2009).

Arrigo, N. & Barker, M. S. Rarely successful polyploids and their legacy in plant genomes. Curr Opin Plant Bio 15, 140–146 (2012).

Brenchley, R. et al. Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature 491, 705–710 (2012).

The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195 (2011).

Chalhoub, B. et al. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345, 950–953 (2014).

Edwards, Dave, Batley, Jacqueline, Parkin, Isobel & Chittaranjan, Kole (ed.) Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Oilseed Brassicas (CRC Press, 2011).

Bundessortenamt. Beschreibende Sortenliste 2016. Getreide, Mais Öl- und Faserpflanzen Leguminosen Rüben Zwischenfrüchte (2016).

Allender, C. J. & King, G. J. Origins of the amphiploid species Brassica napus L. investigated by chloroplast and nuclear molecular markers. BMC Plant Biol 10, 54 (2010).

Sharpe, A. G. & Lydiate, D. J. Mapping the mosaic of ancestral genotypes in a cultivar of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) selected via pedigree breeding. Genome 46 (2003).

Parkin, I. A. P. Segmental Structure of the Brassica napus Genome Based on Comparative Analysis With Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 171, 765–781 (2005).

Schiessl, S., Samans, B., Hüttel, B., Reinhardt, R. & Snowdon, R. J. Capturing sequence variation among flowering-time regulatory gene homologs in the allopolyploid crop species Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 404 (2014).

Cao, J. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple Arabidopsis thaliana populations. Nat Genet 43, 956–963 (2011).

Díaz, A. et al. Copy number variation affecting the photoperiod-B1 and vernalization-A1 genes is associated with altered flowering time in wheat (Triticum aestivum). PLoS ONE 7, 1–11 (2012).

Iovene, M., Zhang, T., Lou, Q., Buell, C. R. & Jiang, J. Copy number variation in potato - an asexually propagated autotetraploid species. Plant J 75, 80–89 (2013).

Springer, N. M. et al. Maize inbreds exhibit high levels of copy number variation (CNV) and presence/absence variation (PAV) in genome content. PLoS Genet 5, e1000734 (2009).

Clop, A., Vidal, O. & Amills, M. Copy number variation in the genomes of domestic animals. Anim Genet 43, 503–517 (2012).

Żmieńko, A., Samelak, A., Kozłowski, P. & Figlerowicz, M. Copy number polymorphism in plant genomes. Theor Appl Genet. 1–18 (2013).

Srikanth, A. & Schmid, M. Regulation of flowering time: all roads lead to Rome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2013–2037 (2011).

Kardailsky, I. et al. Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286 (1999).

Wollenberg, A. C. & Amasino, R. M. Natural variation in the temperature range permissive for vernalization in accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, Cell & Env 35, 2181–2191 (2012).

He, Y. Control of the transition to flowering by chromatin modifications. Mol. Plant 2, 554–564 (2009).

Turck, F. & Coupland, G. When vernalization makes sense. Science 331, 36–37 (2011).

Choi, K. et al. The FRIGIDA complex activates transcription of FLC, a strong flowering repressor in Arabidopsis, by recruiting chromatin modification factors. The Plant Cell 23, 289–303 (2011).

Tadege, M. et al. Control of flowering time by FLC orthologues in Brassica napus . Plant J. 28 (2001).

Pires, J. C. et al. Flowering time divergence and genomic rearrangements in resynthesized Brassica polyploids (Brassicaceae). Biol J Linn Soc 82, 675–688 (2004).

Hou, J. et al. A Tourist-like MITE insertion in the upstream region of the BnFLC.A10 gene is associated with vernalization requirement in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) (2012).

Udall, J. A., Quijada, P. A., Lambert, B. & Osborn, T. C. Quantitative trait analysis of seed yield and other complex traits in hybrid spring rapeseed (Brassica napus L.): 2. Identification of alleles from unadapted germplasm. Theor Appl Genet 113, 597–609 (2006).

Quijada, P. A., Udall, J. A., Lambert, B. & Osborn, T. C. Quantitative trait analysis of seed yield and other complex traits in hybrid spring rapeseed (Brassica napus L.): 1. Identification of genomic regions from winter germplasm. Theor Appl Genet 113, 549–561 (2006).

Nelson, M. N. et al. Quantitative trait loci for thermal time to flowering and photoperiod responsiveness discovered in summer annual-type Brassica napus L. PLoS ONE 9, e102611 (2014).

Raman, H. et al. Genetic and physical mapping of flowering time loci in canola (Brassica napus L.). Theor Appl Genet 126, 119–132 (2013).

Fletcher, R. S., Mullen, J. L., Heiliger, A. & McKay, J. K. QTL analysis of root morphology, flowering time, and yield reveals trade-offs in response to drought in Brassica napus . Ex Bot J (2014).

Bus, A., Hecht, J., Huettel, B., Reinhardt, R. & Stich, B. High-throughput polymorphism detection and genotyping in Brassica napus using next-generation RAD sequencing. BMC Genomics (2012).

Körber, N. et al. Seedling development in a Brassica napus diversity set and its relationship to agronomic performance. Theor Appl Genet 125, 1275–1287 (2012).

Li, R. et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics 25, 1966–1967 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29, 24–26 (2011).

Quinlan, A. R. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army Tool for Genome Feature Analysis. Curr prot bioinf 47, 11.12.1–34 (2014).

Vergara, I. A., Frech, C. & Chen, N. CooVar: Co-occurring variant analyzer. BMC Research Notes (2012).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Meth 9, 357–359 (2012).

Schmutzer, T. et al. Species-wide genome sequence and nucleotide polymorphisms from the model allopolyploid plant Brassica napus . Scientific data 2, 150072 (2015).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Schiessl, S., Iniguez-Luy, F., Qian, W. & Snowdon, R. J. Diverse regulatory factors associate with flowering time and yield responses in winter-type Brassica napus . BMC Genomics 16, 737 (2015).

Aulchenko, Y. S., Ripke, S., Isaacs, A. & van Duijn, C. M. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 23, 1294–1296 (2007).

Deng, W. et al. FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) regulates development pathways throughout the life cycle of Arabidopsis . PNAS 108, 6680–6685 (2011).

Bus, A., Korber, N., Snowdon, R. J. & Stich, B. Patterns of molecular variation in a species-wide germplasm set of Brassica napus . Theor Appl Genet 123, 1413–1423 (2011).

Song, J., Irwin, J. & Dean, C. Remembering the prolonged cold of winter. Current Biology 23, R807–R811 (2013).

Duncan, S. et al. Seasonal shift in timing of vernalization as an adaptation to extreme winter. eLife (2015).

Coustham, V. et al. Quantitative modulation of polycomb silencing underlies natural variation in vernalization. Science 337, 584–587 (2012).

Meyer, S. E., Nelson, D. L. & Carlson, S. L. Ecological genetics of vernalization response in Bromus tectorum L. (Poaceae). Ann Bot 93, 653–663 (2004).

Wu, G., Wu, Y., Xiao, L., Li, X. & Lu, C. Zero erucic acid trait of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) results from a deletion of four base pairs in the fatty acid elongase 1 gene. Theor Appl Genet 116, 491–499 (2008).

Hasan, M. J. & Rahman, H. Genetics and molecular mapping of resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8 in rutabaga (Brassica napus var. napobrassica). Genome 59, 805–815 (2016).

Dittmar, E. L., Oakley, C. G., Agren, J. & Schemske, D. W. Flowering time QTL in natural populations of Arabidopsis thaliana and implications for their adaptive value. Mol Ecology 23, 4291–4303 (2014).

Grillo, M. A., Li, C., Hammond, M., Wang, L. & Schemske, D. W. Genetic architecture of flowering time differentiation between locally adapted populations of Arabidopsis thaliana . New Phytol 197, 1321–1331 (2013).

Chianga, G. C. K., Baruaa, D., Kramera, E. M., Amasinob, R. M. & Donohuea, K. Major flowering time gene, FLOWERING LOCUS C, regulates seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana . PNAS 106, 11661–11666 (2009).

Becker, A. The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Mol Phylogen Evol 29, 464–489 (2003).

Dreni, L. & Kater, M. M. MADS reloaded: evolution of the AGAMOUS subfamily genes. New Phytol 201, 717–732 (2014).

Johansson, M. & Staiger, D. SRR1 is essential to repress flowering in non-inductive conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana . Ex Bot J 65, 5811–5822 (2014).

Wood, C. C. et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana vernalization response requires a polycomb-like protein complex that also includes VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3. PNAS 103, 14631–14636 (2006).

Dorca-Fornell, C. et al. The Arabidopsis SOC1-like genes AGL42, AGL71 and AGL72 promote flowering in the shoot apical and axillary meristems. Plant J 67, 1006–1017 (2011).

Helliwell, C. A., Wood, C. C., Robertson, M., James Peacock, W. & Dennis, E. S. The Arabidopsis FLC protein interacts directly in vivo with SOC1 and FT chromatin and is part of a high-molecular-weight protein complex. Plant J 46, 183–192 (2006).

Xue, J. et al. CCR1, an enzyme required for lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, mediates cell proliferation exit for leaf development. Plant J 83, 375–387 (2015).

Kovi, M. R., Ergon, A. & Rognli, O. A. Freezing tolerance revisited-effects of variable temperatures on gene regulation in temperate grasses and legumes. Curr Opin Plant Bio 33, 140–146 (2016).

Zhou, R., Moshgabadi, N. & Adams, K. L. Extensive changes to alternative splicing patterns following allopolyploidy in natural and resynthesized polyploids. PNAS 108, 16122–16127 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Promoter Variation and Transcript Divergence in Brassicaceae Lineages of FLOWERING LOCUS T. PLoS ONE 7, e47127 (2012).

Nelson, M. N. et al. The loss of vernalization requirement in narrow-leafed lupin is associated with a deletion in the promoter and de-repressed expression of a Flowering Locus T (FT) homologue. New Phytol (2016).

Ding, F. et al. Promoter difference of LcFT1 is a leading cause of natural variation of flowering timing in different litchi cultivars (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Plant science 241, 128–137 (2015).

Searle, I. et al. The transcription factor FLC confers a flowering response to vernalization by repressing meristem competence and systemic signaling In Arabidopsis. Genes & Dev 20, 898–912 (2006).

Deng, W. et al. Direct links between the vernalization response and other key traits of cereal crops. Nat Comms 6, 5882 (2015).

Clarke, W. E. et al. A high-density SNP genotyping array for Brassica napus and its ancestral diploid species based on optimised selection of single-locus markers in the allotetraploid genome. Theor Appl Genet 129, 1887–1899 (2016).

Gaeta, R. T., Pires, J. C., Iniguez-Luy, F., Leon, E. & Osborn, T. C. Genomic Changes in Resynthesized Brassica napus and Their Effect on Gene Expression and Phenotype. The Plant Cell 19, 3403–3417 (2007).

Nicolas, S. D., Monod, H., Eber, F., Chevre, A.-M. & Jenczewski, E. Non-random distribution of extensive chromosome rearrangements in Brassica napus depends on genome organization. Plant J 70, 691–703 (2012).

Udall, J. A., Quijada, P. A. & Osborn, T. C. Detection of Chromosomal Rearrangements Derived From Homeologous Recombination in Four Mapping Populations of Brassica napus L. Genetics 169, 967–979 (2005).

Szadkowski, E. et al. Polyploid formation pathways have an impact on genetic rearrangements in resynthesized Brassica napus . New Phytol 191, 884–894 (2011).

Faria, R. & Navarro, A. Chromosomal speciation revisited: rearranging theory with pieces of evidence. Trends ecol evol 25, 660–669 (2010).

Gaeta, R. T. & Pires, J. C. Homoeologous recombination in allopolyploids: the polyploid ratchet. New Phytol 186, 18–28 (2010).

Valverde, F. et al. Photoreceptor regulation of CONSTANS protein in photoperiodic flowering. Science 303, 1003–1006 (2004).

Gabriele, S. et al. The Dof protein DAG1 mediates PIL5 activity on seed germination by negatively regulating GA biosynthetic gene AtGA3ox1. Plant J 61, 312–323 (2010).

Gallego-Giraldo, C. et al. Role of the gibberellin receptors GID1 during fruit-set in Arabidopsis. Plant J 79, 1020–1032 (2014).

Shi, J. et al. Unraveling the Complex Trait of Crop Yield With Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping in Brassica napus . Genetics 182, 851–861 (2009).

Ridge, S., Brown, P. H., Hecht, V., Driessen, R. G. & Weller, J. L. The role of BoFLC2 in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L.) reproductive development. Ex Bot J 66, 125–135 (2015).

He, Y., Doyle, M. R. & Amasino, R. M. PAF1-complex-mediated histone methylation of FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin is required for the vernalization-responsive, winter-annual habit in Arabidopsis . Genes & Dev 18, 2774–2784 (2004).

Castillejo, C. & Pelaz, S. The Balance between CONSTANS and TEMPRANILLO Activities Determines FT Expression to Trigger Flowering. Current Biology 18, 1338–1343 (2008).

Abe, M. et al. FD, a bZIP Protein Mediating Signals from the Floral Pathway Integrator FT at the Shoot Apex. Science 309, 1052–1056 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by grant SN 14/13-1 from the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the priority programme “Flowering Time Control: From Natural Variation to Crop Improvement.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. and R.S. planned the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.S. performed DNA extraction, data analysis and phenotyping. B.H., D.K. and R.R. performed library preparation and sequencing. SS and RS prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Schiessl, S., Huettel, B., Kuehn, D. et al. Post-polyploidisation morphotype diversification associates with gene copy number variation. Sci Rep 7, 41845 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41845

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41845

This article is cited by

-

Long-insert sequence capture detects high copy numbers in a defence-related beta-glucosidase gene βglu-1 with large variations in white spruce but not Norway spruce

BMC Genomics (2024)

-

Structural variations and environmental specificities of flowering time-related genes in Brassica napus

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2023)

-

Transgressive and parental dominant gene expression and cytosine methylation during seed development in Brassica napus hybrids

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2023)

-

Genome-wide identification, phylogeny, and expression profiling analysis of shattering genes in rapeseed and mustard plants

Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (2022)

-

Non-vernalization requirement in Chinese kale caused by loss of BoFLC and low expressions of its paralogs

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.