Abstract

Gene copy number variation (CNV) is increasingly implicated in control of complex trait networks, particularly in polyploid plants like rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) with an evolutionary history of genome restructuring. Here we performed sequence capture to assay nucleotide variation and CNV in a panel of central flowering time regulatory genes across a species-wide diversity set of 280 B. napus accessions. The genes were chosen based on prior knowledge from Arabidopsis thaliana and related Brassica species. Target enrichment was performed using the Agilent SureSelect technology, followed by Illumina sequencing. A bait (probe) pool was developed based on results of a preliminary experiment with representatives from different B. napus morphotypes. A very high mean target coverage of ~670x allowed reliable calling of CNV, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion-deletion (InDel) polymorphisms. No accession exhibited no CNV, and at least one homolog of every gene we investigated showed CNV in some accessions. Some CNV appear more often in specific morphotypes, indicating a role in diversification.

Design Type(s) | individual genetic characteristics comparison design |

Measurement Type(s) | copy number variation profiling |

Technology Type(s) | DNA sequencing |

Factor Type(s) | gene list • selectively maintained organism |

Sample Characteristic(s) | Brassica napus • leaf |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data (ISA-Tab format)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Polyploid genomes present major challenges for DNA sequence analysis due to their high redundancy. Moreover, inter-subgenomic homology is a driving force for genomic rearrangements1–3, including translocations, inversions, duplications, deletions or homeologous non-reciprocal translocations (HNRTs)1. Translocations are events where genomic blocks are transferred to another chromosomal location in the same orientation, whereas inversions switch the orientation. Duplications are events where genetic regions are copied to another locus, meaning that the affected region increases in copy number, whereas deletions involve a loss of genetic regions from the genome and therefore decrease the copy number of the genes therein. HNRTs are coupled duplication-deletion events, where one region of the genome replaces a respective homeologous genome region. Changes in the frequency of genes or other genomic loci due to duplications, deletions and HNRTs are collectively described as copy number variation (CNV).

Brassica napus (oilseed rape, canola) has become a model plant for studies of polyploidy effects4, having been studied for genomic rearrangements over decades5,6. The strongest effects of genomic rearrangements, with regard to both size and abundance, were observed in synthetic, or resynthesized B. napus1,2,7,8. This indicates that substantial genomic rearrangements occur in the first generations after polyploidisation and are thereafter subjected to selection and fixation2. All the same, CNV can arise at any time and is therefore frequently observed3. With increasing reports associating CNV to major traits in different crop species, like wheat, maize and potato9–11, their detection is growing in importance for genomics-assisted breeding approaches to improve crop adaptation and yield.

Flowering time is an extremely important adaptive trait, with wide-ranging implications for the breeding process in crops like B. napus that are grown in different ecogeographical regions. Flowering time determines the lifecycle to be either annual or biannual and is also important for local adaptation. Biannual and annual B. napus forms have divergent lifecycles, and hence must be bred in separate breeding programs, which in turn lowers diversity in these two genetic pools. While extremely important, flowering time regulation is also highly complex, with studies in model species12,13 implicating over 200 different genes and non-coding RNAs. Polyploidy complicates this network not only by multiplying the gene copy number, but also by invoking potential for gene subfunctionalisation14. Knowledge of the underlying natural variation among B. napus flowering time regulators can help to understand which gene copies are decisive for restoring life cycle traits after introgression from a different gene pool. CNVs can play a central role in such variation15.

Different methodologies have been proposed for the detection of CNVs, either based on hybridization arrays or on next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies3. As the latter deliver additional information like SNPs and InDels, they are better suited to unravel causal variants for trait variation16. Although different approaches exist to calculate CNVs from NGS data, the simplest and most abundant approach is the approximation by calculation read depth or sequence coverage. The read depth approach is based on the assumption that sequencing reads distribute equally over the sequenced space, so that deviations in coverage can be interpreted to indicate deletions or duplications. However, for cost-effective application of DNA resequencing on large panels of genotypes, the sequencing power should be focused on regions of interest, like exomes or groups of genes. This can be done by prior enrichment for loci of interest by hybridization with probes or baits, and different commercial solutions are available for this17. Here, we used the Agilent SureSelect technology (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) for target enrichment. The resulting sequence capture libraries were subjected to Illumina sequencing in single-end mode. Baits were designed for homologs of 35 Arabidopsis thaliana flowering genes, based on sequences from B. napus along with its diploid progenitors B. rapa and B. oleracea, and used for production of 120mer RNA oligonucleotides for hybridization. Sequencing was performed for 280 diverse inbred lines as a part of the ERANET-ASSYST B. napus diversity panel18, containing annual and biannual oilseed, fodder, vegetable and rutabaga forms, along with exotic accessions. The results show a vast variance of SNPs, InDels and CNVs in the different breeding pools. An accompanying publication describes the biological implications of the data15.

Methods

Plant Material and phenotyping

A panel of 280 genetically diverse B. napus inbred lines (self-pollinated for 5 or more generations) was grown in in Giessen, Germany (50° 35′ N, 8° 40′ E) in 2012. The plant material was part of the ERANET-ASSYST B. napus diversity set, described in detail by18–20. Biannuals were grown in autumn-sown trials, whereas annual accessions were grown in spring-sown trials. Plots were sown in a completely randomized block design with a harvest plot size of 3×1.25 m in 1 replicate (containing around 200 plants).

DNA isolation

Leaf material for genomic DNA extraction was harvested in spring 2012 from the field trial in Giessen, Germany. Pooled leaf samples were taken from at least 5 different plants per genotype, immediately shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −20 °C until extraction. Leaf material was ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. DNA was extracted using a common CTAB protocol modified from Doyle and Doyle (1990) as described earlier16. DNA concentration was determined using a Qubit fluorometer and the Qubit dsDNA BR assay kit (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA quantity and purity was further checked on 0.5% agarose gel (3 V/cm, 0.5xTBE, 120 min).

Selection of target genes

As described in ref. 16, a set of 29 A. thaliana flowering time genes was selected to cover the entire genetic network controlling flowering time, including circadian clock regulators (CYCLING DOF FACTOR 1 (CDF1), EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3), GIGANTEA (GI) and ZEITLUPE (ZTL)), the input pathways for vernalisation (EARLY FLOWERING 7 (ELF7), EARLY FLOWERING IN SHORT DAYS (EFS), FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), FRIGIDA (FRI), SHORT VEGTATIVE PHASE (SVP), SUPPRESSOR OF FRIGIDA 4 (SUF4), TERMINAL FLOWER 2 (TFL2), VERNALISATION 2 (VRN2), VERNALISATION INSENSITIVE 3 (VIN3)), photoperiod sensitivity (CONSTANS (CO), CRYPTOCHROME 2 (CRY2), PHYTOCHROME A (PHYA), PHYTOCHROME B (PHYB)) and gibberellin (GIBBERELLIN-3-OXIDASE 1 (GA3ox1)), along with downstream signal transducers (AGAMOUS-LIKE 24 (AGL24), APETALA 1 (AP1), CAULIFLOWER (CAL), FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD), FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), FRUITFUL (FUL), LEAFY (LFY), SQUAMOSA PROMOTOR PROTEIN LIKE 3 (SPL3), SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1), TEMPRANILLO 1 (TEM1), TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1)). On top, we also included 6 further genes: CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSISTED 1 (CCA1), FLAGELLIN-SENSITIVE 2 (FLS2), GLYCIN-RICH PROTEIN 7 (GRP7), GLYCIN-RICH PROTEIN 8 (GRP8), GORDITA (GORD) and SENSITIVITY TO RED LIGHT REDUCED 1 (SRR1), giving a total of 35 genes. The respective Arabidopsis identifiers are given in Supplementary Table S1.

Bait development

Before resequencing the total set of 280 accessions, 4 accessions representing divergent morphotypes were resequenced in a preliminary experiment in order to refine the bait pool (described in ref. 16). At the time, no reference sequence for B. napus was available. Baits were therefore produced on sequences of B. rapa and B. oleracea, using the program eArrayXD. The only exception was the target gene FT, for which promotor and gene sequences from B. napus were kindly made available by Carlos Molina, Christian Albrecht University of Kiel, Germany. A pre-publication draft (version 4.0) of the B. napus ‘Darmor-Bzh’ reference genome sequence assembly became available prior to public release, by generosity of Boulos Chalhoub, INRA, France, Unité de Recherche en Génomique Végétale.

Based on the mapping results of the preliminary experiment, the bait pool was modified in order to improve specificity. Enriched regions found in ref. 16 were classified into target regions and non-target regions by BLAST against the nucleotide database in NCBI. The bait pool was blasted against target and non-target regions (E-value cut-off e−10). Baits which had excessive non-target hits were manually removed. This was the case for bait groups on the target genes FT, FUL and PHYA. For some bait groups (AP1, CO, SOC1), too many baits (>30%) were deleted. In these cases, baits groups (120mer oligonucleotide sequences) were created using the B. napus pre-publication draft reference genome sequence assembly, with the Agilent Genomic Workbench program SureDesign (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). These replaced the corresponding bait groups developed previously using B. rapa or B. oleracea. Bait groups were created using the ‘Bait Tiling’ tool. The parameters were set as follows: Sequencing Technology: ‘Illumina’, Sequencing Protocol: ‘Paired-End long Read (75 bp+)’, ‘Use Optimized Parameters (Bait length 120, Tiling Frequency 1x)’, Avoid Overlap: ‘20’, ‘User defined genome’, ‘Avoid Standard Repeat Masked Regions’. Baits for genes on the minus-strand were developed in sense, while baits on the plus-strand were developed in antisense.

In total, 63 bait groups were created for B. rapa homologs of the target genes, 71 bait groups for B. oleracea homologs and 24 bait groups for B. napus homologs.

Sequence capture and sequencing

Custom bait production was carried out by Agilent Technologies (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the output oligonucleotide sequences from SureDesign. Sequence capture was performed using the SureSelectXT 1 kb–499 kb Custom Kit (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting TruSeq DNA library (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer at the Max Planck Institute for Breeding Research (Cologne, Germany) in 100 bp single read mode.

Sequence data analysis

Mapping

Quality control of the raw sequencing data was performed using FASTQC. Reads were mapped onto version 4.1 of the B. napus ‘Darmor-Bzh’ reference genome sequence assembly21. Mapping was performed using the software SOAP2 (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/soapaligner.html), with default settings and alternatively using the option r=0 to extract uniquely aligned reads. Removal of duplicates, sorting and indexing was carried out with samtools version 0.1.19 (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/). Alignments were visualised using the IGV browser version 2.3.12 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/).

The mean read number was 5.8 M reads, with a s.d. of 1.6 M reads. Only 3% of the sequenced samples had less than 4.2 M reads (mean–s.d.), 11% of the samples had more than 7.3 M reads (mean+s.d.). The mean alignment rate was 87%, while the mean unique alignment rate was 75%, indicating that most of the reads could be mapped specifically (see Data Citation 1 for.bam files). The exact values, along with values for the different subsets, can be found in Table 1.

Specificity and sensitivity

In total, the captured reads aligned to 1184 distinct regions of the B. napus ‘Darmor-Bzh’ v4.1 reference genome with a mean coverage of >10. Of these, a total of 637 regions were annotated as genes, and 184 corresponded to the intended target genes. Two target gene copies (Bna.VIN3.A01 and Bna.VIN3.C01) had insufficient coverage, but were nevertheless included in the target list. A total of 33 regions were identified as targets giving a BLAST hit to the FT promotor. A further 12 regions were identified as pseudogenes of the target genes by blasting the gene sequences to the genome. Therefore, the target included 231 regions. The average target sensitivity17, interpreted as the percentage of target bases covered by sequence reads, was 85.6%. The average target specifity17, or the percentage of bases mapping to the intended target, was 68.0%, and therewith indeed better than in the foregoing experiment16. The target regions had a mean coverage of 670x and a mean normalized coverage of 533x. The mean target coverage over the mean genome-wide coverage, also called the enrichment factor, was about 1206, and therefore also increased compared to the preliminary experiment16 (for an overview of values see Table 2).

Detection of SNPs and InDels

Calling of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was performed with the algorithm mpileup in the samtools toolkit. SNPs were filtered for a minimum mapping quality of 50 and a read depth of ≥10, using vcftools (https://vcftools.github.io/man_latest.html).

For InDel calling, a separate mapping was performed using Bowtie2 (http://sourceforge.net/projects/bowtie-bio/files/bowtie2/), as described in ref. 22. Removal of duplicates, sorting and indexing was carried out with samtools version 0.1.19 (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/). An initial InDel calling was performed using samtools mpileup, and realignment of reads around InDels was performed using GATK (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). A final InDel calling was then performed as described above. InDels were filtered for a minimum mapping quality of 30 and a read depth of 10 or more using vcftools (https://vcftools.github.io/man_latest.html). SNP and InDel annotation was performed using CooVar23.

We called and annotated 13053 SNPs among the 1184 captured regions, of which 5,216 were located in the target regions. Of those, 56 SNPs were either radical mutations, splice variants or stop codon mutations (gain or loss). InDel calling revealed a total of 1894 InDels, with 569 in the target regions. Only 25 InDels were frameshifts, amino acid insertions or splice variants. Potential functional variation was revealed in all homolog groups, although 7 homologs were completely conserved, while 16 carried only silent or synonymous variation. The distribution of variants on target and non-target regions is shown in Figure 1.

CNV detection

Enriched regions and coverage differences were calculated using the bedtools software with multiBamCov (http://bedtools.readthedocs.org/en/latest/). Read coverage for each enriched region was normalised as follows:

coveragenorm=(number of aligned reads per region*total length of genome)/(total number of aligned reads*region length).

Copy number variation (CNV) in a given region was assumed if the ratio of normalised coverage(genotype)/mean normalised coverage (all genotypes) was smaller than 0.5 or higher than 1.5, respectively.

No homolog group was found without CNV, and only two accessions were found which did not carry any CNV among the homologous copies of the target genes. Whereas it is therefore very unlikely to find two genotypes with exactly the same copy numbers, the frequency of a specific CNV among the population is generally low; about 87% of the CNVs had an abundance across the whole population of <10%. Deletions were generally more abundant than duplications (Figure 2) both for the A and C subgenomes, regarding all regions. This is expected, as genomes are known to reduce their gene space after polyploidization24, and corresponds to similar findings from whole-genome resequencing in a diverse panel of synthetic and natural B. napus (Samans et al., submitted). Regarding only genes, duplication and deletion events were almost twice as frequent among C subgenome than A subgenome homologs. This appears surprising, as although the C subgenome is significantly larger25,26, its gene content is comparable to that of the A subgenome. A possible explanation for this apparent genome bias might be that transposons are more active in the C subgenome26, increasing the frequency of small-scale homology and double-strand breaks. Considering only the target genes from the flowering-time network, the ratio was strikingly different, with more duplications of A-subgenome genes than C-subgenome genes, but more deletions of C-subgenome genes than A-subgenome target genes. This indicates that A-subgenome copies had been selected over C-subgenome copies, while the other direction is less frequent. A corresponding bias was also observed by Samans et al. (submitted), who suggested that the size difference between homeologous segments from the A and C subgenomes is the driving force for the directional bias, with HNRT tending to replace larger C-subgenome segments by their smaller homoeologous segments from the A-subgenome. Another possible cause could be that gene copies which co-evolved in the progenitor genomes interact more effectively with each other than they do with copies from the other progenitor, a mechanism already assumed by other authors27. C-subgenome copies might have been affected more often due to the high transposon content, invoking a selective advantage for homeologous exchanges that replaced C-subgenome homologs with A-subgenome copies. As flowering is a major lifecycle axis, flowering genes are under strong selection and should show such an effect more clearly than random genes.

Homeologous gene replacements associated with putative HNRTs were observed frequently among the dataset. Excluding gene copies on non-assembled reference chromosomes (‘x_random’), we found 201 putative HNRT events between homeologous target gene copies, including 165 from A-subgenome to C-subgenome homeologs and 36 from C-subgenome to A-subgenome homeologs. In contrast, we found 448 simple duplications for the same gene copies (259 on A-subgenome and 189 on C-subgenome homeologs) and 490 simple deletions (139 on A-subgenome and 351 on C-subgenome homeologs). Although there is a low but significant correlation (r=0.68***) between the number of simple deletions and duplications on the C subgenome, such a correlation was not observed for the A subgenome. The highest rate of HNRTs was found between the strongly homeologous chromosomes A02/C02 and A03/C03, a finding in line with other authors1. On the other side of the spectrum, gene copies on chromosome A08 could not be associated with HNRTs to any homeologous copies, and only one putative HNRT each was observed for chromosomes A05 and A06, respectively. High HNRT frequencies were only observed at the very ends of chromosomes, whereas gene copies located closer to the center of the chromosomes were generally not involved in exchanges (Figure 3). Similar patterns have been frequently observed in Brassicaceae1,28.

Chromosomes are shown as black vertical lines. Partial chromosomes are indicated by dotted lines at their ends. For chromosomes shown in full length, the total length is given below the chromosome name. Genetic positions are relative approximations. Arrows indicate HNRTs between homeologous copies, either from A-subgenome to C-subgenome homeologs (blue) or from C-subgenome to A-subgenome homeologs (green). The numbers behind the gene names indicate the number of simple duplication or deletion events (not involved in HNRTs) in purple and orange, respectively.

Code availability

All custom codes are supplied at https://github.com/ ‘targeted-deep-sequencing’.

Data Records

The aligned sequence data (.bam files) and metadata are stored at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database, SRP-Study accession SRP087610 (Data Citation 1).

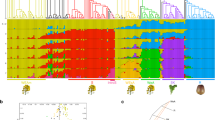

Technical Validation

All biallelic SNP, InDel and CNV data were recoded and included in a population structure analysis together with data from the Brassica 60 K Illumina Infinium SNP array (Clarke et al. 2016, accepted, Mason et al. 2016, accepted). Altogether these include 28,698 markers from the 60k SNP array and 12776 SNPs, 1894 InDels and 366 CNV markers from the present deep sequencing dataset, making a total of 43,733 markers. After pre-processing to filter for non-missing marker values >0.9, minor allele frequency >0.01 and non-missing individual markers >0.8, a total of 33,944 markers and 271 individuals were left, with 30.1% of the markers coming from the deep sequencing data. The subsequent principal component analysis for population structure revealed three main clusters. One cluster contained 137 winter-type B. napus accessions, one contained 93 spring-types and one semi-winter type accession, and the last cluster contained 40 genotypes of mixed origin, comprising mostly beet-forming and semi-winter types. We conclude i) that the variants called from the present deep sequencing dataset represent the species-wide diversity present in B. napus, in accordance with genotyping data from the SNP genotyping array, and ii) that the data correctly describe the study population.

In cooperation with Eleri Tudor from the John Innes Centre, Norwich, the data were compared to three Sanger-sequenced copies of Bna.FRI for 13 (A03 copy), 10 (A10 copy) and 9 (C03 copy) of our genotypes (unpublished data). The overall concordance rate between the data sets was 86%. 5 SNPs on the A03 copy had extremely low concordance rates, possibly due to a mapping problem. Removing those lead to an overall concordance rate of 90%.

We also checked for co-localizing SNPs between the datasets from the SNP genotyping array and from the deep sequencing. A total of 48 suitable SNP pairs were identified which showed apparently corresponding chromosome positions according to the BLAST search. Among this set, 3 SNP pairs had absolutely no correlation, presumably due to incorrect BLAST positions of the array SNP. For the remaining 45 SNPs, we observed a mean concordance of 91.3%, ranging from 83.0 to 97.7% with a standard deviation of 3.5%. These minor discrepancies may arise from the use of different selfing generations of some individuals for the array genotyping and the deep-sequencing. On the other hand, we noticed that concordance was lowest for SNPs discriminating between C and T, potentially suggesting a differential methylation of cytosine nucleotides.

Usage Notes

The plant material described in this paper is publically available and can be made accessible upon request.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Schiessl, S. et al. Targeted deep sequencing of flowering regulators in Brassica napus reveals extensive copy number variation. Sci. Data 4:170013 doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.13 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

References

Gaeta, R. T. & Pires, J. C. Homoeologous recombination in allopolyploids: the polyploid ratchet. New Phytol 186, 18–28 (2010).

Gaeta, R. T., Pires, J. C., Iniguez-Luy, F., Leon, E. & Osborn, T. C. Genomic Changes in Resynthesized Brassica napus and Their Effect on Gene Expression and Phenotype. The Plant Cell 19, 3403–3417 (2007).

Żmieńko, A., Samelak, A., Kozłowski, P. & Figlerowicz, M. Copy number polymorphism in plant genomes. Theor Appl Genet 1–18 (2013).

Mason, A. S. & Snowdon, R. J. Oilseed rape: learning about ancient and recent polyploid evolution from a recent crop species. Plant biology (Stuttgart, Germany) 18, 883–892 (2016).

Lukens, L., Zou, F., Lydiate, D., Parkin, I. A. & Osborn, T. C. Comparison of a Brassica oleracea Genetic Map With the Genome of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 164, 359–372 (2003).

Nicolas, S. D., Monod, H., Eber, F., Chevre, A.-M. & Jenczewski, E. Non-random distribution of extensive chromosome rearrangements in Brassica napus depends on genome organization. Plant J 70, 691–703 (2012).

Pires, J. C. et al. Flowering time divergence and genomic rearrangements in resynthesized Brassica polyploids (Brassicaceae). Biol J Linn Soc 82, 675–688 (2004).

Szadkowski, E. et al. Polyploid formation pathways have an impact on genetic rearrangements in resynthesized Brassica napus. New Phytol 191, 884–894 (2011).

Díaz, A. et al. Copy number variation affecting the photoperiod-B1 and vernalization-A1 genes is associated with altered flowering time in wheat (Triticum aestivum). PLoS ONE 7, 1–11 (2012).

Springer, N. M. et al. Maize inbreds exhibit high levels of copy number variation (CNV) and presence/absence variation (PAV) in genome content. PLoS Genet 5, e1000734 (2009).

Iovene, M., Zhang, T., Lou, Q., Buell, C. R. & Jiang, J. Copy number variation in potato - an asexually propagated autotetraploid species. Plant J 75, 80–89 (2013).

Andrés, F. & Coupland, G. The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat Rev Genet 13, 627–639 (2012).

Blümel, M., Dally, N. & Jung, C. Flowering time regulation in crops-what did we learn from Arabidopsis? Current opinion in biotechnology 32, 121–129 (2015).

Renny-Byfield, S. & Wendel, J. F. Doubling down on genomes: polyploidy and crop plants. American Journal of Botany 101, 1711–1725 (2014).

Schiessl, S., Hüttel, B., Kühn, D., Reinhardt, R. & Snowdon, R. J. Post-polyploidisation morphotype diversification associates with gene copy number variation. Sci. Rep. 7, 41845 (2017).

Schiessl, S., Samans, B., Hüttel, B. & Reinhardt, R. & Snowdon, R. J. Capturing sequence variation among flowering-time regulatory gene homologs in the allopolyploid crop species Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 404 (2014).

Mamanova, L. et al. Target-enrichment strategies for next-generation sequencing. Nat Meth 7, 111–118 (2010).

Bus, A., Korber, N., Snowdon, R. J. & Stich, B. Patterns of molecular variation in a species-wide germplasm set of Brassica napus. Theor Appl Genet 123, 1413–1423 (2011).

Bus, A., Hecht, J., Huettel, B., Reinhardt, R. & Stich, B. High-throughput polymorphism detection and genotyping in Brassica napus using next-generation RAD sequencing. BMC Genomics, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-281 (2012).

Körber, N. et al. Seedling development in a Brassica napus diversity set and its relationship to agronomic performance. Theor Appl Genet 125, 1275–1287 (2012).

Chalhoub, B. et al. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345, 950–953 (2014).

Schmutzer, T. et al. Species-wide genome sequence and nucleotide polymorphisms from the model allopolyploid plant Brassica napus. Scientific data 2, 150072 (2015).

Vergara, I. A., Frech, C. & Chen, N. CooVar: co-occurring variant analyzer. BMC Research Notes 5, 615 (2012).

Sankoff, D., Zheng, C. & Zhu, Q. The collapse of gene complement following whole genome duplication. BMC Genomics 11, 313 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet 43, 1035–1039 (2011).

Parkin, Isobel A. P. et al. Transcriptome and methylome profiling reveals relics of genome dominance in the mesopolyploid Brassica oleracea. Genome Biol 15, doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r77 (2014).

Schnable, P. S. & Springer, N. M. Progress Toward Understanding Heterosis in Crop Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 71–88 (2013).

Drouaud, J. et al. Variation in crossing-over rates across chromosome 4 of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals the presence of meiotic recombination ‘hot spots’. Genome Research 16, 106–114 (2006).

Data Citations

NCBI Sequence Read Archive SRP087610 (2017)

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by grant SN 14/13-1 from the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the priority programme ‘Flowering Time Control: From Natural Variation to Crop Improvement.’

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. and R.J.S. planned the experiments and wrote the manuscript. S.S. performed DNA extraction and data analysis. B.H., D.K. and R.R. performed library preparation and sequencing. We thank Eleri Tudor from the John Innes Centre, Norwich, for her courtesy to assist in validating SNP data for copies of Bna.FRI.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ISA-Tab metadata

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Metadata associated with this Data Descriptor is available at http://www.nature.com/sdata/ and is released under the CC0 waiver to maximize reuse.

About this article

Cite this article

Schiessl, S., Huettel, B., Kuehn, D. et al. Targeted deep sequencing of flowering regulators in Brassica napus reveals extensive copy number variation. Sci Data 4, 170013 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.13

This article is cited by

-

Structural variations and environmental specificities of flowering time-related genes in Brassica napus

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2023)

-

Genomic structural variation in tomato and its role in plant immunity

Molecular Horticulture (2022)

-

A novel deletion in FLOWERING LOCUS T modulates flowering time in winter oilseed rape

Theoretical and Applied Genetics (2021)

-

Target region sequencing and applications in plants

Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology (2021)

-

Gene presence-absence variation associates with quantitative Verticillium longisporum disease resistance in Brassica napus

Scientific Reports (2020)