Abstract

Many advanced technologies have relied on the availability of single crystals of appropriate material such as silicon for microelectronics or superalloys for turbine blades. Similarly, many promising materials could unleash their full potential if they were available in a single crystal form. However, the current methods are unsuitable for growing single crystals of these oftentimes incongruently melting, unstable or metastable materials. Here we demonstrate a strategy to overcome this hurdle by avoiding the gaseous or liquid phase and directly converting glass into a single crystal. Specifically, Sb2S3 single crystals are grown in Sb-S-I glasses as an example of this approach. In this first unambiguous demonstration of an all-solid-state glass → crystal transformation, extraneous nucleation is avoided relative to crystal growth via spatially localized laser heating and inclusion of a suitable glass former in the composition. The ability to fabricate patterned single-crystal architecture on a glass surface is demonstrated, providing a new class of micro-structured substrate for low cost epitaxial growth, active planar devices, etc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inorganic solids generally exist in either a disordered glassy, a polycrystalline ceramic, or a fully ordered single crystal state. A transformation from glass to ceramic is achieved readily by heating the former to a particular temperature that inevitably leads to nucleation of many crystals1,2. In producing a single crystal, the creation of multiple nuclei must be avoided. For this reason, most single crystals are produced today not by solid-solid, but by liquid-solid transformation3 in which the formation of extraneous nuclei during the growth of the initially formed nucleus is unstable in the surrounding liquid phase. However, there is a serious drawback of single crystal growth from melts: such methods are not useful for fabricating crystals of compositions that decompose, transform to some undesirable phase, or melt incongruently on heating4. Consequently, it has been extremely difficult or impossible to grow single crystals of many complex oxides such as high Tc superconductors5, organometallic halide perovskites for solar cells of exceptional efficiency6,7, etc. This lack of high quality crystals is identified as a critical limitation to the progress of materials by design paradigm8. For these materials, elevated temperatures and melting need to be avoided. In principle, this can be achieved by a strategy, in which the glassy material is heated locally by a laser to just its crystallization temperature (Tx), which is well below the melting temperature. Using glass as a precursor and a focused laser as a localized heating source, offers the combined advantages of low cost, of allowing broad composition ranges and of easy formability of single crystals in complex shapes including wires or films. Furthermore, they enable a new materials platform comprising of a ‘single crystal architecture in glass (SCAG)’, in which the single crystal of arbitrary shape can be an active phase with properties such as second order optical nonlinearity, ferroelectricity, pyroelectricity, piezoelectricity, etc., that are not possible in the isotropic structure of glass. Consequently, this method for converting glass to single crystal can have a transformational impact on multiple technologies.

The concept of glass → single crystal transformation could not be realized in the past due to concurrent nucleation at multiple sites, which ultimately produced polycrystalline glass-ceramic instead of single crystal1,2. On the other hand, basic feasibility of SCAG fabrication has been demonstrated recently at or near the surface of glass by Komatsu et al.9, as well as deep inside the glass by Stone et al.10 using continuous wave (CW) and femtosecond (fs) lasers, respectively. However, in all these reports, the single crystal is formed during cooling of molten material that is produced in the vicinity of the laser focus9,10. This process does not have the desired advantages of a solid-state transformation of glass → single crystal and very much resembles the traditional floating zone crystal growth from the melt11.

Although epitaxial conversion of solid amorphized surface film of semiconductors (such as from ion implantation) back to single crystal12 and growth within a polycrystalline solid through seeded conversion have been reported13, there is no evidence in the literature showing all solid- state conversion of bulk solid glass to a single crystal. In contrast to these works, only the single crystal growth that occurs directly from solid glass offers the possibility of SCAG for crystal compositions that melt incongruently, decompose on heating to the melting temperature (Tm), or for which the desired crystalline phase is unstable at temperatures between Tx and Tm. Moreover, the underlying science and mechanism of the phase transformation from melt-to-crystal vis-à-vis directly from glass → crystal are fundamentally different.

So, how can a glass → single crystal transformation be achieved? The basic premise of fabricating a single crystal is simple: establish only one nucleus and then help it grow to the desired dimensions. It is implicit that for this to happen the experimental conditions should inhibit the formation of any other competing nuclei while the initially nucleated crystal grows. This is most readily accomplished by destabilizing nucleation in the vicinity of the growing crystal by maintaining the temperature slightly <Tm, in the metastable Ostwald-Miers supercooled zone1. In this temperature range no nucleation occurs (see Fig. 1a) and an external seed crystal is utilized such as in Czochralski method3.

Temperature dependence of nucleation and crystal growth rates in glass-forming systems and its relationship to laser crystallization.

(a) Prototypical temperature dependence vs. nucleation and growth rate curves. (b) Schematic of the CW laser induced temperature fields in the focal spot at the glass surface, with the temperature lines from (a) representing the lower limits of nucleation and crystal growth temperature range. Small rhombuses indicate the region of unwanted nuclei, while larger rhombus indicates the region of single crystal formation. Tm, Tx, Tn and Tg indicate the temperatures of melting, crystal growth onset, nucleation onset and glass transition.

On the other hand, when one relies on spontaneous nucleation such as in the case of glass devitrification, multiple crystals grow simultaneously resulting in a polycrystalline ceramic. Since the temperature of nucleation onset (Tn) is always lower than Tx1,2, unwanted nuclei are always likely to form and remain stable around the heated region14 as shown schematically in Fig. 1. Notwithstanding, we have devised a strategy that allows us to grow a single crystal using direct crystallization of glass, which involves heating it from ambient to Tx (see Fig. 1). Nucleation is a stochastic process so that its overall probability depends on the volume of the heated region and the time. Heating with a focused laser can limit the volume of glass so that only one nucleus is allowed to form, which is then grown quickly into a single crystal. We show that unwanted additional nucleation can be avoided by decreasing the volume of the heated region and growing the crystal by moving the laser beam at a sufficiently fast rate such that there is no time for forming extraneous crystals.

To validate our strategy and demonstrate proof-of-concept, it is most appropriate to begin with a composition that is within the glass-forming region but not too far from the boundary where crystallization is unavoidable. If the glass is highly stable, the probability of nucleation, especially homogeneous nucleation and hence controlled laser crystallization is too low to test the hypothesis in a reasonable time. On the other hand, if the composition crystallizes too easily, precise observation of the crystallization process, especially single-crystal formation would become difficult. Further, for experimental convenience the glass should be able to absorb readily available laser light in a sufficiently deep region of the sample. A laser that is strongly absorbed just in the very top surface layer (<1 μm) is not desirable, as the nucleation becomes relatively improbable and the crystal growth is not as well controlled. The bandgap of most chalcogenide glasses falls into the visible to near-infrared spectral region, so that light from red lasers is absorbed efficiently and no additional dopants are required in contrast to oxide glasses9,15. Changing the wavelength of the laser diode allows altering the corresponding absorption cross-section conveniently, which would facilitate modification of the temperature profile within the sample, providing a useful tool for optimizing crystal nucleation/growth dynamics.

For all the above-mentioned reasons, we selected Sb2S3 composition as a test example. This simple binary composition belongs to technologically important A2B3 type chalcogenides (A = As, Sb, Bi; B = S, Se, Te), which have been investigated due to their attractive physical and chemical properties16,17,18,19. Consequently, their basic physical, thermodynamic and chemical properties have been determined and are readily available in the literature. Among possible choices, antimony trisulfide (Sb2S3) is particularly attractive because of its interesting ferroelectric properties20 and potential practical applications in solar cells, microwave devices, switching sensors, thermoelectric and optoelectronic devices21,22,23,24,25. To exemplify the impact of the proposed new strategy of single crystal fabrication, we note that this material burns in air at ~300 °C and loses sulfur preferentially upon heating to high temperature in an inert atmosphere26,27,28. Therefore, it is practically impossible to obtain its stoichiometric single crystal by starting from melt using conventional methods.

Results

1-D single crystal fabrication

The success of the space selective laser-induced heating for transforming glass into single crystal is evident from the results shown in Fig. 2, using the example of Sb2S3 glass. We employed a diode laser with wavelength (λ) of 639 nm, which is focused to a few μm on the surface and its intensity is gradually increased from 0 to 50 μW/μm2 in 5 s and then maintained at this value. The first sign of a crystal is observed 2 s thereafter. Within 20 s it reaches the equilibrium dimensions as seen in Fig. 2. The uniform color of inverse pole figure (IPF) maps obtained from electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis confirms that the Sb2S3 glass transformed into a single crystal dot by laser heating (see Supplementary video SV1 for the details).

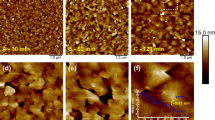

Laser-induced formation of Sb2S3 single crystal line on the surface of Sb2S3 glass.

A laser-induced dot created on the surface of Sb2S3 glass by slowly ramping the laser power density from 0 to 50 μW/μm2 in 5 s, followed by steady exposure for 60 s and its extension into a straight line by moving the laser spot at the speed of 1 μm/s. Scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. (a) SEM image, (b) colored IQ map and orientation IPF maps with reference vector along surface normal (c) and along in-plane direction (d), respectively. EBSD mapping is collected using 70o- inclined geometry, which in the case of rough sample surface results in a “shadow” region inaccessible to the probe electron beam. The white-colored regions on IPF maps inside of the dot correspond to such “shadow” regions.

As the laser beam is subsequently moved laterally across the surface at a rate of 1 μm/s, the growth of the initial dot follows the laser, forming a single crystal line of Sb2S3 as seen in Fig. 2. The orientation IPF maps for both the dot and line exhibit the same color, which confirms that the whole structure is a single crystal of Sb2S3 (Fig. 2c,d).

In order to extend our approach to other materials systems, we further suppressed unwanted nucleation by adding a glass-forming component. This additional strategy can have broad applicability through appropriate choice of glass composition. For its validation, we repeated the above experiments on homogeneous 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass wherein the addition of 16% SbI3 makes glass formation easier and nucleation more difficult relative to Sb2S329. Nevertheless,when heated with a laser beam only Sb2S3 crystalline phase precipitates out either through the evaporation of SbI3 in the heated zone or enrichment of the region around the growing crystal with iodine and antimony. In either case, nucleation in front of the growing crystal is suppressed relative to crystal growth. Figure 3a shows typical morphology of the initial dot (D1), which was induced by laser beam above a minimum threshold intensity of 65 μW/μm2. The energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis maps (Fig. 3e) for this region show deficiency of iodine, which indicates SbI3 evaporation under sustained heating by the laser beam. This change in composition increases the concentration of Sb2S3 and stimulates the formation of its crystal in shallow crater.

Laser-induced formation of Sb2S3 single crystal line on the surface of 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass.

A single-crystal dot (D1) was created by slowly ramping the power density from 0 to 90 μW/μm2 in 5 s, followed by steady exposure for 60 s. Scale bar corresponds to 5 μm. (a) SEM image, (b) IQ and colored orientation IPF maps with reference vectors (c) along surface normal and (d) an in-plane direction for the single-crystal line; (e) SEM image and EDS color maps for sulfur, iodine and antimony in the dot D1 → line L1 transition region. The rough sample surface in part of the dot and beginning of the line do not show an EBSD signal due to the “shadow” effect for the probe electron beam.

To assess the tendency of nucleation relative to the growth of Sb2S3 crystal in 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass, the laser was turned off after forming the single crystal line L1. It took less than 1 s to form a new dot next to the previously formed line L1, compared to ~43 s needed to form the initial dot D1. Therefore, the crystal line can be grown indefinitely using the previously created crystal as a seed.

2-D single crystal fabrication

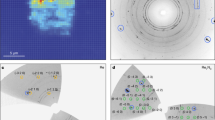

Having demonstrated the feasibility of solid glass → single crystal transformation and the ability to fabricate single crystal lines by eliminating extraneous nucleation, we turned our attention to the realization of 2D crystals, further enhancing the usefulness of solid state crystal growth as a SCAG. Based on Fig. 4, which shows a 2D crystal of Sb2S3 grown on the surface of 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass, it is indeed possible to ‘stitch’ successive lines together to form a 2D crystal. In this approach30, the laser is moved from the initial dot D1 in X- direction at 20 μm/s and the first Sb2S3 single crystal, L1, grows without introducing additional nuclei. To obtain the second line, the end of first line is used as the seed. Laser exposure for the second and subsequent dots (D2–D7) was reduced to 15 s compared to 60 s for D1. Then the second line was written anti-parallel to and overlapping the first line. The subsequent laser- written crystal lines were written similarly, overlapping with the previous line by slightly more than half the width of the previous line. The result is a 2D planar single-crystal structure made via solid-solid transformation, with c-axis orientation normal to the laser scanning direction for the whole area as shown by the EBSD maps in Fig. 4. Each crystal in these dots (D2–D7) and subsequent lines maintains the same orientation. The neighboring lines merge and form the 2D single crystal structure.

2D laser-induced single-crystal architecture fabricated by ‘stitching’ seven lines, L1-L7.

First, a seed dot D1 and line L1 were created on the surface of 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass, as in Fig. 3. New seed dots (D2–D7) were formed from previous lines and then used to grow new lines (L2–L7), correspondingly. To form dots D2–D7 the beam was shifted laterally in the y- direction by 3 μm and the exposure was reduced to 15 s. (a) Plan-view; SEM images (b) before and (c) after repolishing; and orientation IPF maps with reference vectors (d) along surface normal and (e) the in-plane direction, respectively. Scale bar corresponds to 10 μm.

The reproducibility of the observations reported here is excellent as established from experiments on a few tens of dots and lines and several 2D structures using optimal laser irradiation parameters (power, focus position relative to surface, scanning rate, etc.).

Discussion

Previous attempts of crystallization of amorphous Sb2S3 films, which did not follow the strategy developed in the present work, produced only polycrystalline structures31,32. The authors of these investigations used argon laser with a spot size of 400 μm diameter and no attempt was made to maintain the temperature below the melting temperature. Sb2S3 does not form glass easily; it requires very rapid cooling of the melt to form bulk glass, as in this study, or vacuum deposition of its vapor phase to form thin amorphous films prepared by Arun et al.31,32. Therefore, in their work the probability of extraneous nucleation was too high to yield a single-crystal upon heating. This challenge of unwanted nucleation could be successfully overcome by decreasing significantly the heated volume with a finely focused laser beam and addition of SbI3 as a glass stabilizer.

There are two independent key observations pertaining to the premise of this Report, which prove that the glass → single crystal transformation occurs here entirely in the solid state. First, scratches that were present on the glass surface before laser irradiation (seen in Fig. 2c,d, most clearly in the region of the line) persist through the crystallization process, indicating that the nucleation and growth processes occur without forming a melt that would have altered the surface morphology. Second, the in situ observation of the crystal growth process (see Supplementary video SV1) demonstrates that the crystallization occurs at the leading, not the trailing edge of the laser beam. The former region represents the region being heated from ambient to crystallization temperature, while the latter represents the region cooled to ambient from the crystallization temperature. This is a direct indication that the glass transforms into single crystal upon its heating and not during the cooling of the melt that would have happened at the trailing edge of the laser spot14. Thus, these results provide the first unequivocal proof-of-principle that it is possible to transform a glass into single-crystal by heating to crystallization onset temperature (TX), rather than by the usual crystal growth processes via cooling to the crystallization temperature from above the melting point (Fig. 1).

As for the lines fabricated in Sb2S3 glass, the crystallization also occurs at the leading edge of the laser-heated region (see Supplementary video SV2), which confirms the growth of single- crystal Sb2S3 line by the solid state transformation of 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass during heating. The relatively small volume contraction of the line compared to the initial dot in Fig. 3 suggests that the crystal growth occurs by the redistribution of Sb, S and I atoms during growth rather than evaporation of SbI3. The same is also indicated by the depletion of S and enrichment of I just outside the line (arrows in Fig. 3e).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that indeed it is feasible to fabricate SCAG via a completely solid-state transformation. As proof-of-principle, successful examples of 1D and 2D Sb2S3 single-crystal structures are produced on the surface of xSbI3–(1 − x)Sb2S3 glass by employing a strategy, which relies on eliminating extraneous nucleation relative to crystal growth via space localized laser heating below Tm and adding suitable glass former. The new method offers the opportunity to obtain single crystals that may decompose, melt incongruently or undergo phase transformation between the crystallization and melting temperature of the glass.

Methods

Glass preparation

The glasses were made following the ampule quenching method previously developed for the Sb-S-I system33. To make Sb2S3 samples, which does not form glass easily, the melt cooling rate was increased by limiting quartz ampules to 1 mm inside diameter (ID) and 10 μm wall thickness. 16SbI3–84Sb2S3 glass was prepared using ampules with 11 mm ID and wall thickness 1 mm. X-ray diffraction analysis of the as-quenched samples confirmed their amorphous state. For details of glass fabrication and its characterization, please see Supplementary Information, Figs S1–S3. The samples for laser-induced treatments were polished using metallographic techniques.

Laser-induced crystallization. The intensity of the fiber-coupled 639 nm diode laser (LP639- SF70, ThorLabs) used for crystallization, was modulated by an analog voltage (ILX Lightwave LDX-3545 Precision Current Source). The beam was focused onto the sample by a 50x, 0.75NA microscope objective. The sample was placed in a flowing nitrogen environment on a custom- built stage, which could be translated independently in the x-, y- and z-directions. Flow of nitrogen eliminated oxidation of Sb2S3 crystals, which was observed in air environment. A CCD camera monitored the sample in-situ, while LabView software controlled the laser intensity and the movement of the stage. A detailed description of laser crystallization system is presented in Supplementary Information, Fig. S4.

Materials characterization

The laser-irradiated regions were analyzed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi 4300 SE) in water vapor environment to eliminate charging effects. The chemical compositions were determined at multiple locations on each sample by EDS detector attached to SEM, using the EDAX-Genesis software. Local crystallinity and orientation were determined by EBSD with Kikuchi patterns collected by a Hikari detector within the SEM column. EBSD pattern scans were collected and indexed using TSL OIM Data Collection software, whereas Orientation Imaging Microscopy Analysis software yielded image quality, pole figure and inverse pole figure maps34.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Savytskii, D. et al. Demonstration of single crystal growth via solid-solid transformation of a glass. Sci. Rep. 6, 23324; doi: 10.1038/srep23324 (2016).

References

Höland, W. & Beall, G. H. Glass Ceramic Technology Ch.1 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, 2012).

Zanotto, E. D. Bright future for glass-ceramics. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 89, 19–27 (2010).

Feigelson, R. S. 50 years Progress in Crystal Growth, p.105–184 (Elsevier B. V., Amsterdam, 2004).

Mühlberg, M. Phase Diagrams for Crystal Growth In book: Crystal Growth Technology: From Fundamentals and Simulation to Large-scale Production Ch. 1 (Wiley-VCH: Verlag,, 2008).

Scheel, H. J. & Licci, F. Crystal growth of high temperature superconductors. MRS Bulletin 13, 56–61 (1988).

Mitzi, D. B. Synthesis, structure and properties of organic-inorganic perovskites and related materials. Prog. Inorg. Chem. 48, 1–121 (1999).

Hsiao, Y.-C. et al. Fundamental physics behind high-efficiency organo-metal halide perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 15372–15385 (2015).

National Research Council Frontiers in Crystalline Matter: From Discovery to Technology p. 77 (National Academies Press, Washington DC, 2009).

Komatsu, T. et al. Patterning of non‐linear optical crystals in glass by laser‐induced crystallization. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 90, 699–705 (2007).

Stone, A. et al. Direct laser-writing of ferroelectric single-crystal waveguide architectures in glass for 3D integrated optics. Sci. Rep. 5, 10391 (2015).

Brice, C. J. Crystal Growth Processes (Halsted Press, New York, 1986).

Cullis, A. G. Transient annealing of semiconductors by laser, electron beam and radiant heating techniques, Rep. Prog. Phys. 48, 1155–1233 (1985).

Scott, C. E., Strok, J. M. & Levinson, L. M. Solid state thermal conversion of polycrystalline alumina to sapphire using a seed crystal. U.S. Patent No. 5, 549,746. 27, Aug. 1996.

Biegelsen, D. K. et al. Laser-induced crystal growth of silicon islands on amorphous substrates: in Laser and Electron-Beam Solid Interactions and Materials Processing (Elsevier, 1981).

Honma, T., Benino, Y., Fujiwara, T., Komatsu, T. & Sato, R. Technique for writing of nonlinear optical single-crystal lines in glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 2796–2798 (2003).

Zakery, A. & Elliott, S. R. Optical Nonlinearities in Chalcogenide Glasses and Their Applications (Springer, New York, 2007).

Arivuoli, D., Gnanam, F. D. & Ramasamy, P. Growth and microhardness studies of chalcogenides of arsenic, antimony and bismuth. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 7, 711–713 (1988).

Chen, B. & Uher, C. Transport properties of Bi2S3 and the ternary bismuth sulfides KBi6.33S10 and K2Bi8S13 . Chem. Mater. 9, 1655–1658 (1997)

Suarez, R., Nair, P. K. & Kamat, P. V. Photoelectrochemical behavior of Bi2S3 nanoclusters and nanostructured thin films. Langmuir 14, 3236–3241 (1998).

Varghese, J., Barth, S., Keeney, L., Whatmore, R. W. & Holmes, J. D. Nanoscale ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties of Sb2S3 nanowire arrays. Nano Lett. 12, 868–872 (2012).

Rajpure, K. Y. & Bhosale, C. H. Sb2S3 semiconductor-septum rechargeable storage cell. Mater. Chem. Phys. 64, 70–74 (2000).

Grigas, J., Meshkauska, J. & Orliukas, A. Dielectric properties of Sb2S3 at microwave frequencies. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 37, K39–K41 (1976).

Wu, L., Xu, H. Y., Han, Q. F. & Wang, X. Large-scale synthesis of double cauliflower-like Sb2S3 microcrystallines by hydrothermal method. J. Alloys Comp. 572, 56–61 (2013).

Kim, I. H. (Bi, Sb)2(Te, Se)3-based thin film thermoelectric generators. Mater. Lett. 43, 221–224 (2000).

Kim, D.-H. et al. Highly reproducible planar Sb2S3-sensitized solar cells based on atomic layer deposition. Nanoscale 6, 14549–14554 (2014).

Živković, Ž., Štrbac, N., Živković, D., Grujičić, D. & Boyan, B. Kinetics and mechanism of Sb2S3 oxidation process. Thermochim. acta 383, 137–143 (2002).

Padilla, R., Aracena, A. & Ruiz, M. C. Kinetics of stibnite (Sb2S3) oxidation at roasting temperatures. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B- Metall. 50, 127–132 (2014).

Meyer, B. Elemental sulfur. Chem. Rev. 76, 367–388 (1976).

Turyanitsa, I. D., Mel’nichenko, T. N., Shtets, P. P. & Rubish, V. M. Vitrification, structure and properties of alloys in Sb-S-I system. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Neorg. Mater. 22, 2047–2051 (1986). In Russian.

Suzuki, F., Ogawa, K., Honma, T. & Komatsu, T. Laser patterning and preferential orientation of two-dimensional planar β-BaB2O4 crystals on the glass surface. J. Solid State Chem. 185, 130–135 (2012).

Arun, P., Vedeshwar, A. G. & Mehra, N. C. Laser-induced crystallization in Sb2S3 films. Mat. Res. Bull. 32, 907–913 (1997).

Arun, P., Vedeshwar, A. G. & Mehra, N. C. Laser-induced crystallization in amorphous films of Sb2C3 (C = S, Se, Te), potential optical storage media. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 32, 183–190 (1999).

Gupta, P., Stone, A., Woodward, N., Dierolf, V. & Jain, H. Laser fabrication of semiconducting ferroelectric single crystal SbSI features on chalcohalide glass. Opt. Mater. Exp. 1, 652–657 (2011).

Orientation Imaging Microscopy (OIM™) Data Analysis, (2016). http://www.edax.com/Products/EBSD/OIM-Data-Analysis-Microstructure-Analysis.aspx

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Basic Energy Sciences Division, Department of Energy (DE- SC0005010). B.K. was supported by NSF (DMR-0906763).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S., V.D. and H.J. designed the overall research and interpreted results; D.S. prepared the samples, designed and implemented characterization methods and analyzed results; B.K., D.S. and V.D. designed laser writing setup; H.J., V.D. and D.S. wrote the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Savytskii, D., Knorr, B., Dierolf, V. et al. Demonstration of single crystal growth via solid-solid transformation of a glass. Sci Rep 6, 23324 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23324

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23324

This article is cited by

-

Synthesis and characterization of ambient-processed all-inorganic perovskite CsPbBr2Cl micro-crystals and rods

Chemical Papers (2022)

-

Non-resonant power-efficient directional Nd:YAG ceramic laser using a scattering cavity

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Recent advances, challenges, and opportunities of inorganic nanoscintillators

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2020)

-

Single Crystal Growth via Solid → Solid Transformation of Glass

Transactions of the Indian Institute of Metals (2019)

-

Fabrication of graded index single crystal in glass

Scientific Reports (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.