Abstract

Sodium ion secondary battery (SIB) is a low-cost and ubiquitous secondary battery for next-generation large-scale energy storage. The diffusion process of large Na+ (ionic radius is 1.12 Å), however, is considered to be slower than that of small Li+ (0.76 Å). This would be a serious disadvantage of SIB as compared with the Lithium ion secondary battery (LIB). By means of the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), we determined the diffusion constant (D) of Na+ in thin films of O3- and P2-type NaCoO2 with layered structures. We found that the D values (~ 0.5–1.5 × 10−10 cm2/s) of Na+ are higher than those (< 1 × 10−11 cm2/s) of Li+ in layered LiCoO2. Especially, the D values of O3-NaCoO2 are even higher than those of P2-NaCoO2, probably because O3-NaCoO2 shows successive structural phase transitions from the O3, O’3, P’3, to P3 phases with Na+ deintercalation. We further found that the activation energy (ED ~ 0.4 eV) for the Na+ diffusion is significantly low in these layered cobalt oxides. We found a close relation between the relative capacity and the renormalized discharge rate ( = L2/DT, where L and T are the film thickness and discharge time, respectively).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The SIBs store electric energy by the intercalation/deintercalation of abundant Na+ (Clark number = 2.63) and hence, are suitable for large-scale batteries that will enable the stable use of solar and wind energies1,2,3. Recently, Komaba et al.4 have found that hard carbon shows a high capacity of more than 200 mAh/g and good cyclability. This finding opens the door to the commercial utilization of SIB technologies and hence, significantly stimulates investigation and exploration of cathode materials for SIBs. Among the cathode materials for SIBs1,2, layered transition metal oxides (NaMO2, where M is transition metal) show promising electrochemical properties5,6 as well as rich structural properties7,8,9. We have much wider selections of sodium compounds, e.g., transition metal and stacking structure, as compared with those of the lithium compounds. For example, O3-NaCrO2 shows a capacity of 120 mAh/g and an average operating voltage of 3.0 V (vs. Na) with good cyclability in SIBs10 while isostructural O3-LiCrO2 shows a poor capacity and cyclability in LIBs. In addition to the O3-type staking, i.e., close-packed AB|CA|BC stacking of oxygen sheets along the c-axis, the sodium compounds frequently exhibit the P2-type staking, i.e., close-packed AB|BA stacking of oxygen sheets. For example, P2-Na0.6MnO211 shows a capacity of 140 mAh/g and an average operating voltage of 2.5 V (vs. Na). The Na deficiency of the P2-type compound, however, is serious drawback in the actual process of manufacture, because an extra electrochemical process is needed to compensate the Na deficiency.

SIBs are considered for stationaly energy storage bacause the diffusion process of large Na+ (ionic radius is 1.12 Å) is believed to be slower than that of small Li+ (0.76 Å). However, the Na+ diffusion is really dependent on the crystal structure. For example, the Na+ diffusion in P2-Na0.66Li0.22Ti0.78O2 with layered structure12 and Na3V2(PO4)313 with NASICON (Na Super Ionic CONductor) structure are considerably fast, while it is much slower in Li4Ti5O1214,15 with spinel structure. In order to precisely determine the Na+ diffusion constant (D), we fabricated thin films of O3- and P2-type NaCoO2 on an Au collector electrode by means of the pulsed laser deposition (PLD) method. We found that the D values (~ 0.5–1.5 × 10−10 cm2/s) of Na+ are higher than those (1 × 10−11 cm2/s16) of Li+ in layered LiCoO2. We further extracted a close relation between the relative capacity and the renormalized discharge rate ( = L2/DT), with eliminating the voltage drop effects, i.e., -IR, in the rate-dependence of discharge curves.

We first determined the crystal structures of O3-type Na0.99CoO2 and P2-type Na0.67CoO2 by Rietveld analysis (Rietan-FP17) based on the synchrotron-radiation X-ray powder diffraction pattern obtained at BL02B2 beamline18 of SPring-8, Japan (Figs. S1 and S2). Figure 1 shows the Na+ diffusion path of (a) O3-type Na0.99CoO2 and (b) P2-type Na0.67CoO2 together with the actual inter-oxygen distances. In the O3-type stacking, Na+ is located in the oxygen octahedron and migrates to the neighboring site through the oxygen isosceles triangle, 2.84 Å in base and 3.64 Å in oblique side19. The triangle window is rather narrow for Na+: the optimal distance ( = 1.97 Å) to the three vertexes is much smaller than the sum ( = 2.52 Å) of the ionic radii of Na+ (1.12 Å) and O2− (1.4 Å). In the P2-type stacking, Na+ is located in oxygen triangular prism and migrates to the neighboring site through the oxygen rectangle, 2.83 Å in base and 3.57 Å in height. The rectangle window is wide for Na+: the optimal length ( = 2.28 Å) to the four vertexes is comparable the sum ( = 2.52 Å) of the ionic radii. Thus, the Na+ diffusion is considered to be faster in the P2-type stacking with oxygen prisms.

Na+ diffusion path of (a) O3-type Na0.99CoO2 and (b) P2-type Na0.67CoO2.

Upper panels show Na+ layers (large yellow spheres) together with the sandwiching oxygen layers (small red spheres). Red arrows and blue marks indicate the Na+ diffusion path and the oxygen window, respectively. Lower panels show the oxygen window together with the ionic radii of Na+ (1.12 Å) and O2− (1.40 Å).

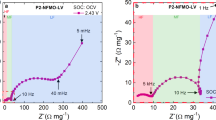

In order to determine D and ionic charge-transfer resistance (Rct), we performed the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of thin films of O3-NaCoO2 and P2-NaCoO2 (Figs. S5 and S6). The EIS curves were analyzed by least-squares fitting with the Randle equivalent circuit [Fig. 2(a)]. In the analysis, we used a constant phase element (CPE)-restricted diffusion impedance,  and

and  20. As shown in Fig.2 (b), this model well reproduced the overall feature of the EIS curve, i.e., semicircle in the high-frequency region and bending behavior in the low frequency region. Especially, the CPE-restricted diffusion impedance reproduced the finite slope in the low frequency limit. Thus obtained D and Rct were plotted in Figs. 2(c) and (d). The D values of O3-NaCoO2 are even higher than those of P2-NaCoO2 [Fig. 2(c)], the origin of which will be discussed later. Importantly, the D values (~ 0.5–1.5 × 10−10 cm2/s) of Na+ in layered cobalt oxides are much higher than those (< 1 × 10−11 cm2/s16) of Li+ in LiCoO2. We note that the experimentally-obtained D values in layered cobalt oxides are comparable to the calculated one (~ 2.1 × 10−10 cm2/s12) of P2-Na0.66Li0.22Ti0.78O2. In the high-x region (x > 0.82) of P2-NaxCoO2, the high-frequency semicircle is too deformed to be analyzed at 303 K (Fig. S5). The EIS curves of P2-NaxCoO2 (x = 0.5) show no bending behavior in the low frequency region in the temperature range from 303 K to 349 K (Fig. S6). This implies that the D value at x = 0.5 is much higher than those at x = 0.54 − 0.72. This is probably due to the Na+/vacancy ordering. On the other hand, the Rct values of O3-NaCoO2 are much smaller than those of P2-NaCoO2.We further estimated the activation energies of D and Rct by Arrhenius plot (Fig. S7). In the high-x region (x > 0.82) of P2-NaxCoO2, the activation energies of D and Rct can be evaluated because the deformations of the EIS curves are released above 318 K (Fig. S6). The activation energies (ED ~ 0.4 eV) of D in O3-NaCoO2 are comparable to those in P2-NaCoO2. On the other hand, the activation energies (ER ~ 0.3 eV) of Rct in O3-NaCoO2 are slightly lower than those (~ 0.4 eV) in P2-NaCoO2.

20. As shown in Fig.2 (b), this model well reproduced the overall feature of the EIS curve, i.e., semicircle in the high-frequency region and bending behavior in the low frequency region. Especially, the CPE-restricted diffusion impedance reproduced the finite slope in the low frequency limit. Thus obtained D and Rct were plotted in Figs. 2(c) and (d). The D values of O3-NaCoO2 are even higher than those of P2-NaCoO2 [Fig. 2(c)], the origin of which will be discussed later. Importantly, the D values (~ 0.5–1.5 × 10−10 cm2/s) of Na+ in layered cobalt oxides are much higher than those (< 1 × 10−11 cm2/s16) of Li+ in LiCoO2. We note that the experimentally-obtained D values in layered cobalt oxides are comparable to the calculated one (~ 2.1 × 10−10 cm2/s12) of P2-Na0.66Li0.22Ti0.78O2. In the high-x region (x > 0.82) of P2-NaxCoO2, the high-frequency semicircle is too deformed to be analyzed at 303 K (Fig. S5). The EIS curves of P2-NaxCoO2 (x = 0.5) show no bending behavior in the low frequency region in the temperature range from 303 K to 349 K (Fig. S6). This implies that the D value at x = 0.5 is much higher than those at x = 0.54 − 0.72. This is probably due to the Na+/vacancy ordering. On the other hand, the Rct values of O3-NaCoO2 are much smaller than those of P2-NaCoO2.We further estimated the activation energies of D and Rct by Arrhenius plot (Fig. S7). In the high-x region (x > 0.82) of P2-NaxCoO2, the activation energies of D and Rct can be evaluated because the deformations of the EIS curves are released above 318 K (Fig. S6). The activation energies (ED ~ 0.4 eV) of D in O3-NaCoO2 are comparable to those in P2-NaCoO2. On the other hand, the activation energies (ER ~ 0.3 eV) of Rct in O3-NaCoO2 are slightly lower than those (~ 0.4 eV) in P2-NaCoO2.

Na+ diffusion constant (D) and ionic charge-transfer resistance (Rct) of layered cobalt oxides.

(a) Randles equivalent circuit: high frequency resistance of electrolyte (Ro), ionic charge-transfer resistance (Rct), double layer capacitance (Cdl) and restricted diffusion. impedance [ , Rd and zd are characteristic resistance and reduced diffusion impedance, respectively] of flat plate with thickness L. (b) Complex impedance of P2-NaCoO2 at x = 0.60. Red curve is results of the least-squares fitting of with the Randles equivalent circuit: Ro = 170 Ω, Rct = 460 Ω, Cdl = 0.62 μF, Rd = 2500 Ω, D = 0.83 × 10−10 cm2/s, α = 0.40 and n = 0.77. (c) D, (d) Rct (e) activation energy (ED) of D and (f) activation energy (ER) of Rct. against x.

, Rd and zd are characteristic resistance and reduced diffusion impedance, respectively] of flat plate with thickness L. (b) Complex impedance of P2-NaCoO2 at x = 0.60. Red curve is results of the least-squares fitting of with the Randles equivalent circuit: Ro = 170 Ω, Rct = 460 Ω, Cdl = 0.62 μF, Rd = 2500 Ω, D = 0.83 × 10−10 cm2/s, α = 0.40 and n = 0.77. (c) D, (d) Rct (e) activation energy (ED) of D and (f) activation energy (ER) of Rct. against x.

The open-current-voltage (OCV) discharge curve slightly different between O3-type and P2-type NaCoO2 (black curves in Fig.3). The layered cobalt oxides are known to show successive structural phase transition with Na+ intercalation/deintercalation. The phase transition causes the voltage drop at single phase point and the voltage plateau in two phase region. Lie. et al.21 systematically investigated the structural properties of O3-NaxCoO2 against x. They found four phases, i.e., the O3 (x = 1.00), O’3 (monoclinic phase: x = 0.83), P’3 (monoclinic phase: x = 0.67) and P3 (x ~0.5) phases. In the O’3phase, Na+ is located in the oxygen octahedron as in the O3-type. In the P’3 and P3 phases, Na+ is located in the oxygen prisms as in the P2-type. Actually, we observed four voltage drops in the discharge curve of O3-NaCoO2, which correspond to the O3, O’3, P’3 and P3 phases (Fig. S8). In addition, the inter CoO2-sheet distance (~ 5.44 Å) of the oxidized film (x = 0.65) is much longer than that (~ 5.14 Å) of the as-grown film, (Fig. S3) suggesting the P3-type structure21. These observations indicate that the O3-NaxCoO2 film (0.5 < x < 0.83) contains the P3 (or P’3) phases. Then, the unexpected high-D values observed in O3-NaCoO2 [see Fig.3(c)] are ascribed to the P3-type host framework with oxygen prisms. On the other hand, Berthelot et al.8 investigated the structural properties of P2-NaxCoO2 against x. They found three phases, i.e., the x = 0.72, 0.76 and 0.79 phases, in addition to the well-known x = 1/2 and 2/3 phases. These phases are ascribed to the Na+/vacancy ordering within the P2-type host framework. We observed three voltage drops in the discharge curve of P2-NaCoO2, which correspond to the 1/2, 3/2 and ~ 0.76 phases (Fig. S8).

Figure 3 shows discharge curve of (a) O3-NaCoO2 and (b) P2-NaCoO2 at various discharge rates. The fast discharge properties observed in thin films are probably ascribed to the ideal electronic contact between the active material and the collector electrode. Generally, the discharge process is governed by the electric conductivity (or voltage drop) and Na+ diffusion process. We first eliminated the voltage drop effect (-IR: I and R is the current density and battery resistances) by changing the cut-off voltage for evaluation of the capacity (Q) as 2.5 V - IR. The R values are 477 Ω in Ο3-NaCoO2 (L = 320 nm), 660 Ω in Ο3-NaCoO2 (L = 330 nm) and 1160 Ω in Ο3-NaCoO2 (L = 170 nm). Then, the residual rate-dependence can be ascribed to the Na+ diffusion effect. Here, let us consider one-dimensional diffusion equation, , where n is the Na+ density. We introduce dimensionless time and depth scales, i.e., α ( = x/L) and β ( = t/T), where T is the time needed for the full discharge. In other words, system is fully-discharged at β = 1. Then, we obtained a renormalized diffusion equation,

, where n is the Na+ density. We introduce dimensionless time and depth scales, i.e., α ( = x/L) and β ( = t/T), where T is the time needed for the full discharge. In other words, system is fully-discharged at β = 1. Then, we obtained a renormalized diffusion equation,  . This equation indicates that the diffusion dynamics scales with the renormalized discharge rate (L2/DT), irrespective of the individual L, D and T values.

. This equation indicates that the diffusion dynamics scales with the renormalized discharge rate (L2/DT), irrespective of the individual L, D and T values.

Figure 4 shows relative capacities (Q/Q0: Q0 is the OCV capacity) of three films against L2/DT. The Q/Q0 value begins to decrease when L2/DT approaches ~ 0.1 while it remain nearly ~ 1 in the small-L2/DT region. The decrease, commonly observed in three films, should be ascribed to the Na+ diffusion process. The solid curve in Fig.4 is the result of simulation of discharge process. The simulation was performed by difference calculus with the space mesh (Nα) of 30 and time mesh (Nβ) of 20,000 (Fig. S9). At the active material/electrolyte boundary (α = 0), we forces a constant Na+ intercalation ( = Nα /Nβ). The Na+ intercalation stops if the density ( = 1 – n) of the Na+ vacancy at α = 0 becomes smaller than Nα /Nβ. The β value at this condition corresponds to Q/Q0. The simulated curve begins to decreases at L2/DT ~ 0.1 and well reproduces the global feature of the experiment.

Relative capacity (Q/Q0) against renormalized discharge rate (L2/DT).

L, D and T are the film thickness, Na+ diffusion constant and discharge time, respectively. Q0 and Q are the open-current-voltage (OCV) capacity and actual capacity, respectively. The capacities are evaluated at 2.5 V - IR, where I and R is the current density and battery resistances. Solid curve is the results of simulation based on the one-dimensional diffusion equation. The data of P2-NaCoO2 (open squares) were cited from ref. 22.

In summary, we fabricated thin films of O3- and P2-type NaCoO2 by means of the PLD method and precisely determined the magnitudes and activation energies of D and RCT. We found that the D values (~ 0.5–1.5 × 10−10 cm2/s) for the Na+ diffusion are much higher than those (< 1×10−11 cm2/s16) for the Li+ diffusion in layered cobalt oxides. Especially, the D values of O3-NaCoO2 are even higher than those of P2-NaCoO2. This is probably because oxidized O3-NaxCoO2 film (0.5 < x < 0.83) contains the P3-type host framework with oxygen prisms. We further found that the activation energy (ED~ 0.4 eV) for the Na+ diffusion is significantly low in these layered cobalt oxides. Our experiment indicates that we can explore active materials with high Na+ diffusion even though the diffusion process of larger Na+ was believed to slower than that of small Li+.

Method

Film synthesis and characterization

This film of O3-NaCoO2 (P2-NaCoO2) was grown on Au-deposited MgO (100) substrate at 823 K (923 K) in an oxygen partial pressure of 0.01 Pa (50 Pa) for 10–30 min by pulsed laser deposition (PLD) method. The film thickness (L) was 200–400 nm and the film area was 0.5 cm2. L was determined by cross-sectional SEM image, after the electrochemical measurements. The mass of the active material was estimated by L and the actual density of the film, which was evaluated with a larger and thicker film. The second harmonics of an yttrium–aluminum–garnet (YAG) pulse laser was used as excitation light source. The pulse energy, repetition frequency and wavelength were 2.0 J/cm2, 10 Hz and 532 nm, respectively. The distance between the target and the substrate was 35 mm. The sodium concentration of the film was assumed to be the same as the target, which was determined by Rietveld structural analysis (Figs. S1 and S2). The targets of O3-Na0.99CoO2 (P2-Na0.67CoO2) were prepared by solid state reaction. First, Na2O2 (Na2CO3) and Co3O4 were mixed in a 1.25: 1.0 (0.7: 1.0) atomic ratio and calcined at 823 K (1073 K) for 16 h (12 h) in O2 atmosphere (air). Then, the O3-NaCoO2 (P2-NaCoO2) powder was finely ground, pressed into pellets with 2 mm in diameter and calcined at 823 K (1073 K) for 16 h (12 h) in O2 atmosphere (air). We confirmed the (003) and (006) [(002) and (004)] reflections in the X-ray diffraction pattern (Fig. S3) of O3-NaCoO2 (P2-NaCoO2), indicating the (001)-orientation of the films. The scanning electron microscope (Fig. S4) revealed that the O3-NaCoO2 (P2-NaCoO2) film consists of grains of ~ 100 nm (300–500 nm) in diameter.

Electrochemical measurement

The discharge properties were investigated using a two-pole beaker type cell with a battery charge/discharge system (HOKUTO HJ-SD8). The cathode and anode were the film and Na, respectively. The electrolyte was propylene carbonate (PC) containing 1 mol/L NaClO4.The lower and upper cut-off voltages vs. Na were 1.5 V (2.0 V) and 3.8 V (3.4 V) for O3-NaCoO2 (P2-NaCoO2), respectively. The charge current was set to 4 μA/cm2. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was carried out with a potentiostat (BioLogic VSP). The frequency range was from 5 mHz to 200 kHz and the amplitude was 30 mV.

Analysis of the EIS data

The EIS data were analyzed by Randles equivalent circuit [see Fig. 2(a)] with high frequency resistance of electrolyte (Ro), ionic charge-transfer resistance (Rct), double layer capacitance (Cdl) and restricted diffusion impedance [ , Rd and zd are characteristic resistance and reduced diffusion impedance, respectively] of flat plate with thickness L. We used the CPE-restricted form,

, Rd and zd are characteristic resistance and reduced diffusion impedance, respectively] of flat plate with thickness L. We used the CPE-restricted form,  and

and  20. The CPE-restricted diffusion impedance becomes the well-known forms in special cases:

20. The CPE-restricted diffusion impedance becomes the well-known forms in special cases:  at

at  (perfectly-reflective boundary) and

(perfectly-reflective boundary) and  at

at  (perfectly-absorptive boundary). The seven parameters, i.e., Ro, Rct, Cdl, RD, α, n and D, were determined by least-squares fittings of the EIS curves.

(perfectly-absorptive boundary). The seven parameters, i.e., Ro, Rct, Cdl, RD, α, n and D, were determined by least-squares fittings of the EIS curves.

References

Kim, S.-W., Seo, D.-H., Ma, X., Ceder, G. & Kang, K. Electrode materials for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries: potential alternatives to current lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 710–721 (2010).

Ong, S. P. et al. Voltage, stability and diffusion barrier differences between sodium-ion and lithium-ion intercalation materials. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3680–3688 (2011).

Pan, H., Hu, Y.-S. & Chen, L. Room-temperature stationary sodium-ion batteries for large-scale electric energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2338–2360 (2013).

Komaba, S. et al. Electrochemical Na insertion and solid electrolyte interphase for hard-carbon electrodes and application to Na-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 21, 3859–3567 (2011).

Yabuuchi, N. et al. P2-type Nax[Fe1/2Mn1/2]O2 made from earth-abundant elements for rechargeable Na batteries. Nature Mater. 11, 512–517 (2012).

Yoshida, H., Yabuuchi, N. & Komaba, S. NaFe0.5Co0.5O2 as high energy and power positive electrode for Na-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 34, 60–63 (2013).

Medarde, M. et al. 1D to 2D Na+ ion diffusion inherently linked to structural transitions in Na0.7CoO2 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 266401 (2013).

Berthelot, R., Carlier, D. & Delmas, C. Electrochemical investigation of P2- NaxCoO2 phase diagram. Nature Mater. 10, 74–80 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Direct visualization of the Jahn–Teller effect coupled to Na ordering in Na5/8MnO2 . Nature Mater. 13, 586–592 (2014).

Komaba, S., Takei, C., Nakayama, T., Ogata, A. & Yabuuchi, N. Electrochemical intercalation activity of layered NaCrO2 vs. LiCrO2 . Electrochem. Commun. 12, 355–358 (2010).

Caballero, A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of high-temperature hexagonal P2-Na0.6MnO2 and its electrochemical behavior as cathode in sodium cells. J. Mater. Chem. 12, 1142–1147 (2002).

Wang, Y. et al. A zero-strain layered metal oxide as the negative electrode for long-life sodium-ion batteries. Nature Commun. 4, 2365–2370 (2013).

Jian, Z. et al. Superior electrochemical performance and storage mechanism of Na3V2(PO4)3 cathode for room-temperature sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Meter. 3, 156–160 (2013).

Sun, S. et al. Direct atomic-scale confirmation of three-phase stage mechanism in Li4Ti5O12 anodes for room-temperature sodium-ion batteries. Nature Commun. 4, 2365–2370 (2013).

Yu, X. et al. A size-dependent sodium storage mechanism in Li4Ti5O12 investigated by a novel characterization technique combining in situ X-ray diffraction and chemical sodiation. Nano Lett. 13, 4721–4727 (2013).

Xia, H., Meng, Y. S., Lu, L. & Ceder, G. Electrochemical behavior and Li diffusion study of LiCoO2 thin film electrode prepared by PLD. J. Power Sources 159, 1422–1427 (2006).

Izumi, F. & Momma, K. Three-dimensional visualization in powder diffraction, J. Solid State Phemom. 130, 15–20 (2007).

Nishibori, E. et al. The large Debye–Scherrer camera installed at SPring-8 BL02B2 for charge density studies. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 467–468, 1045–1048 (2001).

Van der Ven, A., Ceder, G., Asta, M. & Tepesch, P. D. First-principles theory of ionic diffusion with nondilute carriers. Phys. Rev. B64, 184307 (2001).

Bisquert, J., Garcia-Belmonte, G., Fabregat-Santiago, F. & Bueno, P. R. Theoretical models for ac impedance of finite diffusion layered exhibiting low frequency dispersion. J. Electroanal. Chemistry 475, 152–163 (1999).

Lei, Y., Lie, X., Liu, L. & Ceder, G. Synthesis and stoichiometry of different layered sodium cobalt oxides. Chem, Mater. 26, 5288–5298 (2014).

Shibata, T., Kobayashi, W. & Moritomo, Y. Intrinsic rapid Na+ intercalation observed in NaxCoO2 thin film. AIP Advance 3, 032104 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid (No. 23684022) for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. The synchrotron-radiation X-ray powder diffraction experiments were performed at the SPring-8 BL02B2 beamline with the approval (2014A1056 and 2012B1753) of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. M. planed the overall the experiment and wrote the main manuscript. T. S. synthesized the thin films and analyzed the impedance spectra. K. W. fabricated the PLD chamber and Y. F. make a least-squares fitting program with the CPE-restricted diffusion impedance.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shibata, T., Fukuzumi, Y., Kobayashi, W. et al. Fast discharge process of layered cobalt oxides due to high Na+ diffusion. Sci Rep 5, 9006 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09006

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09006

This article is cited by

-

Chloride electrode composed of ubiquitous elements for high-energy-density all-solid-state sodium-ion batteries

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Potentials of Zea mays L. silk mediated bio-synthesized NaCr0.1Co0.4Ni0.5O2 nanoparticles for sodium-ion supercabattery applications

Ionics (2023)

-

Structural and electrochemical kinetics of Na–Fe–Mn–O thin-film cathode: a synergistic effect of deposition conditions

Ionics (2021)

-

Electrochemical properties and first-principle analysisof Na x [M y Mn1−y ]O2 (M = Fe, Ni) cathode

Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry (2018)

-

Nanostructured Na-ion and Li-ion anodes for battery application: A comparative overview

Nano Research (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.