Abstract

What leads healthy individuals to abnormal feelings of contact with schizophrenia patients remains obscure. Despite recent findings that human bonding is an interactive process influenced by coordination dynamics, the spatiotemporal organization of the bodily movements of schizophrenia patients when interacting with other people is poorly understood. Interpersonal motor coordination between dyads of patients (n = 45) or healthy controls (n = 45) and synchronization partners (n = 90), was assessed with a hand-held pendulum task following implicit exposure to pro-social, non-social, or anti-social primes. We evaluated the socio-motor competence and the feeling of connectedness between participants and their synchronization partners with a measure of motor coordination stability. Immediately after the coordination task, all participants were also asked to rate the likeableness of their interacting partner. Our results showed greater stability during interpersonal synchrony in schizophrenia patients who received pro-social priming, inducing in their synchronization partner greater feelings of connectedness towards patients. This greater feeling of connectedness was positively correlated with stronger motor synchronization between participants suggesting that motor coordination partly underlies patients' social interactions and feelings of contact with others. Pro-social priming can have a pervasive effect on abnormal social interactions in schizophrenia patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social interaction deficits are one of the most significant and defining features of psychiatric disorders and are particularly common in schizophrenia1,2. These deficits affect patients' long-term functioning, outcomes and quality of life. However, they are only partially explained by clinical symptom severity3. There is a range of non-exclusive factors that contribute to social interaction deficits in schizophrenia patients. This disorder usually develops in a life period when people learn essential occupational and social skills. Negative symptoms, hostility, lack of motivation, unemployment, financial difficulties and stigma are likely to reduce patients' social functioning and number of social interactions4,5.

Biological and cognitive theories have been the dominant frameworks to account for such deficits during the past twenty years6. However, abnormal and “bizarre” motor behaviors like posturing or aimless excess motor activity, as described by early psychiatrists, were considered as characteristic of some individuals with schizophrenia, leading to a lack of rapport and feelings of connectedness with these patients7. Recent paradigmatic changes also give rise to an accumulation of evidence that motor behavior and particularly its inter-individual dynamics, constitute a strong and necessary conveyor of social skills and become overwhelming8 in humans' studies. Surprisingly, in spite of such a growing body of literature showing the huge impact of motor behaviors on social exchanges, little attention has yet been paid to this aspect of human communication in schizophrenia9,10,11 and has been neglected in psychiatric science.

For example, there is now evidence that mimicry, the automatic tendency to imitate others' behavior (e.g. postures, facial expressions) during social interactions enhances empathy and social exchanges by generating attitudes of cooperation and affiliation12,13,14. In addition to behavioural matching (e. g. mimicry), it has been demonstrated that synchrony plays a fundamental role during communicative nonverbal behavior15,16,17,18. This interactional synchrony has been defined by Bernieri and Rosenthal19 as the smooth meshing in time of the simultaneous rhythmic activity of two interactors. Importantly, research on interactional synchrony has found that the degree of interactional synchrony of the bodily movements of co-actors during social interaction predicts subsequent affiliation ratings19, increases rapport20 and cooperation21 between individuals. Thus, the spatiotemporal organization of the bodily movements of interacting people and more particularly interpersonal coordination16 plays a fundamental role in enhancing connectedness, social rapport or cohesion in human interactions22. Numerous methods have been used to measure such temporal coordination between two individuals23. Such between-people measures are aimed at capturing complex whole body human movement both in terms of the number of moving components and the time-unfolding nature of its movement patterns (e.g. postural mirroring24) or mutual eye gaze24. Previous research has shown the relevance of dynamical systems theories to examine social motor coordination17 including paradigms where two people sitting side by side are moving rhythmically, These researches demonstrated that daily interpersonal coordination of arms or postures when two people have verbal exchanges is best described, understood, explained and predicted by the so-called dynamical entrainment processes of coupled oscillators24,25 (each individual being considered an oscillator). These dynamical processes guide interactional synchrony seen in everyday interactions and are considered the best actual tool to investigate socio-motor competences and their deficits26.

To our knowledge, only one study27 explored interpersonal coordination in individuals with schizophrenia. Varlet et al.27 assessed non-verbal interaction comparing healthy and schizophrenia patients when performing social motor coordination by oscillating hand-held pendulums. They showed that unintentional coordination was preserved while intentional coordination was impaired, particularly for a difficult pattern of motion (moving the pendulums in opposite directions). They also showed that this effect was modulated by the social role (i.e. leadership conditions: leader, neutral or follower) of the participant during the interaction, manipulated using the inertial properties of the pendulums. The importance of this exploratory result was confirmed by a more recent study showing that unaffected first-degree relatives of schizophrenia patients presented similar deficits in intentional interpersonal coordination. Consequently, it has been proposed that intentional interpersonal coordination might be a potential motor intermediate endophenotype of schizophrenia28. However, the question whether the consequences of such impairments have an impact on everyday social interactions, such as the feeling of connectedness, remains unclear. Previous research on healthy subjects has shown that the emergence and stability of such unintended or intended coordination is closely associated with affiliation and social cohesion18,19. Thus, it is necessary to investigate whether improving interpersonal motor coordination in schizophrenia patients can improve both their social connectedness to others and their social functioning in general.

Interpersonal motor coordination, a very similar behaviour to mimicry, is often unconscious, occurs spontaneously29 and might also be sensitive to priming paradigms. The present paper explores for the first time whether social semantic priming could enhance interpersonal motor coordination in schizophrenia patients.

Priming classically refers to the process by which a given stimulus activates mental pathways, thereby enhancing the ability to process subsequent stimuli related to the priming stimulus. Since long, semantic priming has been the standard paradigm for evaluating the priming phenomenon30. There is now accumulation of evidence that priming tasks can facilitate cooperative behaviors and induce a feeling of social attitude/affiliation between two individuals31,32. For example, Over and Carpenter32 have shown that children primed with photographs evoking affiliation helped more often and more spontaneously a person in need, than when primed with photographs evoking individuality. Lakin and Chartran14 also showed that individuals primed by subliminal words related to the concept of affiliation (e.g. together or friend) increased mimicry in a subsequent social interaction. Although their results indicated that enhanced psychological (implicit) attitudes using priming could lead to more automatic mimicry in healthy individuals, it remains largely unknown whether such effects can be generalized to a social illness such as schizophrenia.

In the present study, we combined, on the one hand, human movement paradigms specifically dedicated to study non-verbal bodily social interactions (swinging hand-held pendulums29) and on the other hand, a well-known psychological procedure dedicated to the priming of social attitudes. The main reason for the use of an implicit priming is the fact that most of synchronization in everyday life (i.e. mimicry) occurs spontaneously and without the acting person's conscious awareness. Thus and importantly, implicit priming does not necessarily require any motivational processes or deliberate decision that have been shown impaired in schizophrenia patients. Hence, we investigated whether social priming might influence voluntary socio-motor coordination of schizophrenia patients. Expecting that social priming affects social exchanges33, we hypothesized better performances in interpersonal motor coordination for pro-socially primed schizophrenia participants than for non-socially or anti-socially primed participants. Additionally, social sciences studies demonstrated that the motor system influences our cognition and that our cognition affects our bodily actions, encapsulating this mutual influence under the term of embodiment34,35. We expected an embodied effect of the social priming, that is, a link between a greater motor coordination and an increased feeling of connectedness between participants.

Results

Participants' group comparisons

Median age of schizophrenia patients (Mdn = 33; range: 19–54) and age-matched healthy controls (Mdn = 28; range: 20–56) were statistically equivalent (U = 883, z = −1.05, p = .30, r = .11; see Table 1). However, the schizophrenia group included more males (64%) than the control group (36%, χ2 (1) = 15.68, p < .0001). The socio-motor competence, evaluated by the index of synchronization between participants and their synchronization partners during the coordination task, was impaired for the schizophrenia group with respect to the control group (F(1,84) = 14.37, p < .001, ηp2 = .15; respectively M = .85, SD = .015 and M = .92, SD = .08) irrespective of the leadership condition. Importantly, such impairment (averaged across leadership conditions) was not correlated with age (r = .16, p = .29) and was not explained by group differences in terms of gender (t (88) = −1.37, p = .17, r = .14; Male: M = .84, SD = .14 and Female: M = .87, SD = .11). Finally, movement frequency observed in the SOLO condition was not different between schizophrenia patients and age-matched healthy controls (Table 1) indicating that any general motor slowing among groups do not explain such results.

Social priming effects on sociomotor performance

Sociodemographic data and clinical measures revealed no difference between priming conditions for either the schizophrenia patients and the age-matched healthy controls (Table 2). A 2 Participants' group (Schizophrenia/Control) × 3 Priming Group (Pro-social/Non-social/Anti-social) × 3 Leadership (Follower/Neutral/Leader) ANOVA with a repeated measure was conducted on the index of synchronization. In addition to the Participants' group main effect shown earlier (F(1,84) = 14.37, p < .001, ηp2 = .15), this analysis revealed a significant Leadership main effect (F(2,168) = 11.22, p < .001, ηp2 = .12), a significant Participants' group × Leadership interaction (F(2,168) = 3.05, p < .05, ηp2 = .04) and a significant Priming Group × Leadership interaction (F(4,168) = 2.85, p < .05, ηp2 = .06). Newman-Keuls decomposition of the Participants' group × Leadership interaction showed a significant decrease in sociomotor competence when schizophrenia patients were leader of the coordination with respect to the other conditions and to the control group (Figure 1). A Newman-Keuls decomposition of the Priming Group × Leadership interaction showed that for both schizophrenia and control groups, in the leader condition, pro-social priming increased the sociomotor performance compared to the non-social or anti-social priming (Figure 2). We showed no significant correlations between NSS and interpersonal coordination performances (all p > .05) in neither the schizophrenia group nor the control group. It is important to note here that neither the NSS nor the Positive and Negative PANSS subscales were statistically different for the three schizophrenia priming sub-groups (Table 2). It indicates that priming effects cannot be attributed to differences between the groups in terms of symptomatology (e.g. blunted affects, distrust), individual sensory integration, motor abnormalities or sequencing of complex motor acts.

Mean Index of Synchronization for the Participants' group × Leadership interaction (Error bars correspond to the within standard deviation, N = 45).

Columns 1 to 3 correspond to the Control group and columns 4 to 6 correspond to the Schizophrenia group. Colors indicate the leadership condition: Follower (white columns), Neutral (gray columns), Leader (black columns).

Mean Index of Synchronization for the Priming group × Leadership interaction (Error bars correspond to the within standard deviation, N = 15).

Columns 1 to 3 correspond to the Follower condition, columns 4 to 6 correspond to the Neutral condition and columns 7 to 9 correspond to the Leader condition. Colors indicate the priming conditions.

Sociomotor competence and feeling of connectedness

We also analyzed the affiliation judgment scores obtained after the coordination task. The analysis did not reveal any significant difference when schizophrenia patients or age-matched control participants had to judge their respective synchronization partner. Importantly, significant effects were revealed when the synchronization partners (not-primed) had to judge the schizophrenia or age-matched control participant (Figure 3). This analysis showed a significant participants' group effect (H(1, N = 90) = 12.15, Z = 3.44, p < .001) indicating that age-matched healthy control participants were better judged than schizophrenia. However, a follow-up analysis revealed that schizophrenia patients who were pro-socially primed were better judged by their synchronization partner than schizophrenia patients anti-socially primed (t(28) = −2.24, p < .05) and, moreover, they were equally judged than age-matched healthy control participants (t(28) = 1.06, p = .3). To bridge the gap between the sociomotor competence and these results on the feeling of connectedness towards schizophrenia patients, we conducted a correlational analysis between the affiliation judgment score obtained after the coordination task and the index of synchronization. This analysis showed that the increase in sociomotor competence in the leader condition was associated with an increase in the affiliation judgment score towards schizophrenia patients (r = .24, p = .001).

Mean of the Total score questionnaire for the synchronization partner judging his control partner or his schizophrenia partner, as a function of the priming condition (Error bars correspond to the within standard deviation, N = 15).

Columns 1 to 3 correspond to the Control group and columns 4 to 6 correspond to the Schizophrenia group. Colors indicate the priming conditions. Theoretical score ranged from 0 for the lowest possible score to 12 for the highest.

Discussion

This study has three main findings. First, it confirmed that intentional interpersonal motor coordination is impaired in schizophrenia. Second, pro-social priming increased the stability of interpersonal coordination for both the patient group and the control group. Third, healthy synchronization partners reported a better feeling of connectedness towards schizophrenia patients when the patients were pro-socially primed.

Our first results are in line with and extend previous findings indicating that schizophrenia patients are abnormally coordinated with people they interact with, particularly with regards to their bodily movements36,37,38. In their study concerning interpersonal motor coordination, Varlet et al.27 showed that intentional but not unintentional interpersonal coordination was impaired for schizophrenia patients and mainly when participants had to move in synchrony but in opposite directions. Using the same experimental paradigm, we thus focused on intentional coordination using this difficult pattern of coordination. As revealed by the main participants' groups effect on the synchronization, our results confirmed that dyads with a schizophrenia patient had poorer coordination than dyads with two healthy participants, mainly when schizophrenia patients were expected to lead the coordination, which can be considered as the most difficult condition27.

Secondly, an important result of this study was that pro-social priming significantly increased the coordination performance of both groups, whereas anti-social or non-social priming did not change the stability of the coordination. This result extends our understanding of priming effects for different reasons. Firstly, despite enduring disputed results concerning increased affiliation between people following exposure to pro-social or affiliative stimuli39,40, our study is the first to provide evidence that social priming influences a fundamental motor aspect of human bonding, that is, voluntary sociomotor coordination. More precisely and in line with Lakin and Chartrand's ideas about mimicry14, which is the tendency to unconsciously imitate other's actions15, we found that unconscious social priming can enhance the stability of an explicit motor coordination task. Associated with recent knowledge that the motor system influences our cognition and that our cognition affects our bodily actions41, our results support the idea of an embodied effect of social priming, bridging the gap between human bonding and bodily communication.

Thirdly and very importantly, we found that being primed, whatever the social valence of the priming, didn't affect the way participants judged their synchronization partners. On the other hand, our results indicated that the social priming affected the way primed schizophrenia patients, but not primed age-matched healthy controls, were judged by their synchronization partners. More specifically, synchronization partners reported a better connectedness feeling towards pro-socially primed schizophrenia patients than non-socially or anti-socially primed schizophrenia patients. Moreover, pro-social priming gets schizophrenia patients as “likable” than age-matched healthy controls, whereas it was not the case for the two others primed schizophrenia groups which also exhibited a less stable motor coordination. In addition, affiliation judgment scores significantly correlated with an increase in the stability of the coordination. Importantly even if likability ratings could have been influenced by group differences in motor abnormalities (despite randomization), a correlational analysis showed that « the increase in sociomotor competence in the leader condition (synchronization) was associated with an increase in the affiliation judgment score (likability ratings) towards schizophrenia patients (r = .24, p = .001). Furthermore no difference between the three schizophrenia groups regarding neurologic soft signs and symptoms (positive and negative) were found. Therefore, one can infer that increasing motor coordination stability by virtue of a pro-social priming procedure increased the feeling of connectedness towards schizophrenia patients from non-primed participants (synchronization partners). In other words, these results suggest that this better stability of pro-socially primed schizophrenia patients was perceived by their synchronization partners, leading to a « normalization » of their affiliation towards them in a similar way than healthy controls.

These findings have important treatment significance. To our knowledge, no study has attempted to prime a feeling of social affiliation in order to promote social behaviors, such as interpersonal coordination, in schizophrenia. While several studies have shown that nonverbal behavior during social interaction were significantly impaired in schizophrenia expressive behaviors13,42 and were linked with an important reduction of social competences43 and social functioning13, the original finding of our study is that pro-social priming leads to a better feeling of connectedness in the healthy partner interacting with an individual with schizophrenia.

From a clinical perspective two distinct treatment implications emerge from our findings: First, training patients to improve interpersonal motor coordination through a sensorimotor approach27 or oxytocin administration44 may improve social attunement. Even if our results showed that schizophrenia patients did not experience a greater feeling of connectedness towards their synchronization partner, despite an increase of their interactional synchrony, this better interpersonal synchrony stability, in turn, increased in their interacting partners the motivation to affiliate with them. This could constitute an indirect path to reduce stigmatization behaviors (e.g. increase of social distance) that are partly the consequence of “bizarre” behaviour and interpersonal coordination deficits present in individuals with schizophrenia. In other words, a better ability to synchronize with others could have a causal effect on motivation to affiliate with schizophrenia patients. Second, pro-social priming may facilitate such training. Moreover, it has been recently shown that a priming procedure administered twice daily as an adjunction of cognitive behavioral therapy increased cognitive modifications in social phobics45. Taken together, such interventions could make a significant contribution and constitute an augmentation strategy to the existing behavioral therapies dedicated to promote social skills in schizophrenia patients.

We caution, however, that social interactions in our study were relatively short and took place with unfamiliar partners. In fact, others' response patterns might not be generalizable to longer interactions or those between patients and familiar partners. In addition, further experimentation needs to be conducted to measure the strength of the priming effect, its retention over time and its transferability to social functioning, particularly in daily life activities. It is however important to note that the encouraging result of a recent study45 in individuals with social phobia suggest that a priming procedure repeated during several weeks can have long-term effects and be long lasting even in a clinical population. In addition, it is important de note that we did not control for the valence and arousal characteristics of the anti- and pro-social semantic material (i.e. words). As there is now converging evidence that allocation of attention to emotional stimuli depends upon arousal and valence, we cannot totally exclude that the priming effect found in our study, rather than reflect on the social valence of our semantic material, better reflects its emotional characteristics. Finally, the lack of control of these variables could also explain the absence of any difference between the no- and anti-social conditions concerning motor coordination. Further study are needed to better explore the respective role of valence and of arousal in social priming.

Schizophrenia has long been described as a disorder of intersubjectivity, with patients' social rapport described by classical psychopathologists in terms of “bizzarerie du contact” (Minkowski46) or “Praecox-Gefuhl” (Rumke47), corresponding to this intuitive feeling of lack of contact and connection with patients occurring without any verbal indicators, mainly conveyed by nonverbal and motor behaviours. As postulated by some authors, abnormalities of motor behaviors during social interactions (e.g. described as mannerism and posturing in classical psychiatric literature) might lead other individuals to believe that patients are unpredictable and may be dangerous, which can result to reduced friendships1, increased interpersonal distance2 and stigmatization5. In conclusion, this study put forward some original findings. It shows that interpersonal motor coordination plays a fundamental role in this lack of feeling of “resonance” encountered with schizophrenia patients and provides evidence for how priming effect and interactional synchrony should be considered as an important additional tool and target respectively, for psychosocial treatment for schizophrenia.

Methods

Participants

We included 180 participants: 45 schizophrenia outpatients, 45 age-matched healthy participants and 90 healthy synchronization partners.

Patients were recruited from the University Department of Adult Psychiatry (CHRU Montpellier, France) and fulfilled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders48 criteria for schizophrenia. Diagnoses were established using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV-TR (SCID49). All patients received antipsychotic medication. Exclusion criteria for both the clinical and nonclinical groups were: (a) known neurological disease, (b) Axe II diagnosis of developmental disorders or (c) substance abuse in the past month. All participants were native French speakers with a minimal reading level validated using the fNART test and were able to understand the stimuli in the priming session described below.

Age-matched healthy participants and healthy synchronization partners were recruited from a call for participation in the hospital's website and the community. They had no lifetime history of any psychosis diagnoses according to the SCID. All participants provided written informed consent, prior to the experiment, approved by the National Ethics Committee (CPP Sud Méditérannée III, Nîmes, France, #2009.07.03ter and ID-RCB-2009-A00513-54) conforming to the Declaration of Helsinki. The methods in the current study were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Prior to the experiment, the forty-five schizophrenia patients were randomly paired with forty-five healthy synchronization partners of the same gender, named synchronization partners 1 to compose the Schizophrenia group and the forty-five matched control participants were paired with forty-five healthy synchronization partners of the same gender, named synchronization partners 2 to compose the Control group. Although synchronization partners 1 and synchronization partners 2 were unmatched with the schizophrenia patients and controls, synchronization partners 1 and synchronization partners 2 groups were matched between them in terms of age and level of education. Within the Schizophrenia and Control groups, each pair was randomly assigned to one of three priming subgroups (Pro-social, Non-social or Anti-social). We then obtained six groups: 2 groups of participants (Schizophrenia group and Control group) for each of the 3 priming groups (Pro-social, Non-social or Anti-social).

Procedure

See appendix 1 in Supplement information for details.

One or two days before the experiment, all participants were rated with the Neurological Soft Signs Scale (NSS50) to assess subtle abnormalities in sensory-perceptual, motor functions directly associated with schizophrenia pathology51,52 or induced by neuroleptic medications53. Schizophrenia patients also completed the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS54).

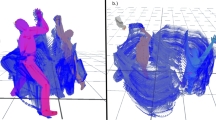

The experimental procedure was split in three parts described bellow (figure 4). The first part was the priming test applied on the experimental participants only (schizophrenia patients or matched controls); the second part was the coordination task using the hand-held pendulums; and finally, the last part was a debriefing questionnaire for all participants. Following recent recommendations from the social psychology literature39,40, our participants were fully naïve about the real goal of the experiment and also about the diagnosis of the schizophrenia patients. To prevent any “un-blind experimenter effect”, five different experimenters ran this experiment (no statistical difference between raters was found in the data analysis). Finally, the experimenters were present in the experimental room but never intervened during the trials. They were neither visible nor audible to the participants. Their role consisted in giving the instructions, running the computer software and controlling that no unpredictable events happened during the experiment.

Experimental design and procedure description.

Panel A (top): 1. Priming test using a scrambled sentence task was applied on the experimental participants only (Schizophrenia patients or age-matched healthy controls); 2. coordination task using the hand-held pendulums consisted in performing movements in opposite directions while watching each other's pendulum; 3. Both participants of a dyad rated the feeling of connectedness towards each other using a “pen and paper” debriefing questionnaire. Panel B (bottom-left): Pendulum combination corresponding to the three leadership conditions (a. Pendulum held by the primed participant; b. Pendulum held by the synchronization partner; c. Mass located on the bottom to create a slow pendulum; d. Mass located on the top to create a fast pendulum; e. Ergonomic handle; f. Aluminum frame supporting the pendulum axis). Panel C (bottom-right): 10 s sample of recorded time series of participants performing the coordination in opposite directions. This figure has been genuinely created by MV and RNS. MV used the 3D softwares Poser 8 and CINEMA 4D R12 for the 3D environment. RNS used Blender 2.7, Photoshop CS6, Illustrator CS6, Powerpoint for Mac 2011 and Matlab 2013b to finalize the rendering.

Social Priming

We implemented an implicit priming task with a cover story to prevent participants from linking the priming task and the coordination task. Upon arrival, participants were informed that they had to perform two distinct experiments. The first one investigated the “role played by color on grammar and sentence construction”, whereas the second one was an “interpersonal coordination task designed to investigate the ability to synchronize with a synchronization partner”.

Participants were then told to swing the pendulums for familiarization (i.e. “SOLO trials”). These trials were used to measure participants' natural movement frequency. Each participant was asked to perform four ‘SOLO’ trials: two with each pendulum (LOW and HIGH), in a random order. They were instructed to hold the pendulum firmly in their hand and to swing it at their own self-selected tempo, “a tempo they found comfortable and could maintain for hours if needed”. All patients and age-matched healthy participants oscillated pendulums with their right hand whereas all healthy synchronization partners (1 and 2) oscillated pendulums with their left hand.

After this familiarization with the pendulums, only patients and age-matched healthy participants were primed using the Scrambled Sentence Task55 [see appendix 2 in Supplement information for details]. Participants in each priming group (Pro-social, Non-social or Anti-social) were primed using an appropriate set of words (as defined by a pilot study, including schizophrenia and healthy raters, presented in appendix 2 in Supplement information). The Pro-social set included words such as “friend” or “team”; the Non-social set included words such as “plate” or “tree”; and the Anti-social set included words such as “selfish” or “alone”. Each priming session was performed in two randomly presented parts. In both parts, five scrambled words written with random colors were presented on a screen (Figure 4). Only one sentence could be written using four of these words (e.g. “wooden is friend she my” yields “she is my friend” for a pro-social sentence), the fifth word was named the intruder (e.g. “wooden”). Once the words were presented on the screen, participants had to mentally reconstruct the right sentence and then to push the “space” keyboard. Once the key pressed, a black screen appeared and the participants had to say the answer to the experimenter. In the first part, participants had to say the full four-word sentence, without the intruder. In that case, the “primed” word (pro-social, non-social or anti-social depending on the condition) was part of the sentence they repeated. In the second part, participants had to tell the experimenter the intruder word. In that case, the intruder corresponded to the “primed” word. Each of these priming tasks contained 12 sentences for each priming group. Each sentence was presented to the participants in a random order. Once the priming session ended, synchronization partners joined their corresponding participant for the interpersonal coordination task.

Interpersonal coordination task

Once together, participants were reminded that the experiment was investigating rhythmic movements with handheld pendulums (Figure 4). They were also reminded that they would be required to do their best to coordinate their movements simultaneously in opposite directions for sixty seconds. After the instructions, each pair performed one trial with the three different leadership conditions defined by the schizophrenia outpatients or the age-matched healthy participants' social role in the interaction: the Follower condition, the Neutral condition and the Leader condition (i.e. respectively the LOW_HIGH, LOW_LOW and HIGH_LOW pendulum combinations, Figure 4). These combinations (LOW_HIGH, LOW_LOW and HIGH_LOW) corresponded respectively to the pendulums used by schizophrenia patients and synchronization partners 1 for the group Schizophrenia and the matched control participants and synchronization partners 2 for the group Control. The order of trials was counterbalanced across dyads.

Affiliation assessment

Immediately after the coordination task, all participants were individually asked to answer a debriefing questionnaire assessing three items: 1) an evaluation of the degree of affiliation between participants, 2) whether participants were aware of the link between the two tasks and 3) whether participants were aware about the social manipulation of the words. The first item corresponded to two randomly presented questions using a Likert scale quoting from “0 = Not at all” to “6 = Absolutely”. The questions were: “Did you find that your partner was likeable?” and “Would you have enjoyed spending more time with your partner?” [The exact French enunciation of the questions was: “Avez-vous trouvé sympathique la personne avec qui vous venez de faire la tâche de coordination avec les pendules?” and “Est-ce que vous auriez aimé passer plus de temps avec cette personne?”]. These questions, inspired from Lakin and Chartrand14, aimed at measuring the subjective feeling of connectedness between participants.

Statistical Analysis

The experimental design was composed of two between-subject independent variables: a participants' group factor (Schizophrenia group and Control group) and a priming group factor (Pro-socially primed group, Non-socially primed group and Anti-socially primed group) for a total of 6 independent groups as well as one within-subject independent variable: the leadership factor (Follower, Neutral and Leader).

Demographic characteristics data were separately compared for the schizophrenia and the control groups with a non-parametric U-Mann-Whitney test or a χ2 test for binary variables (e.g. gender); and for the three priming groups with a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Pairwise comparisons between groups were performed using a t-test when necessary. The level of significance was set to p < .05 and was corrected using the Bonferroni procedure when necessary.

Times series of participants recorded during the coordination task were low-pass filtered using a 10 Hz Butterworth filter and the first five seconds of each trial were discarded to avoid transient behavior. To examine the coordination task, we calculated the continuous relative phase between the two angular positions of pendulums using the Hilbert transform. From the computed relative phase time series, we calculated the intensity of the first Fourier mode of the distribution as the index of synchronization ranging from 0 to 1, which is an indicator of the stability of the coordination56,57. A value of 1 indicates a perfect synchronization whereas a value of 0 reflects an absence of synchronization57,58. Group differences and interactions were analyzed with ANOVA tests. Post-hoc tests were used when the nature of the effects had to be specified. Size effects on our repeated ANOVA design have been reported using the partial eta squared ηp259 and interpreted following Cohen60 where .02 corresponds to a small effect, .13 to a medium effect and .26 to a large effect. When necessary, alpha value of significance was corrected using the Bonferroni procedure.

References

Giacco, D. et al. Friends and symptom dimensions in patients with psychosis: a pooled analysis. PLoS One 7, e50119 (2010).

Kidd, S. A. From social experience to illness experience: reviewing the psychological mechanisms linking psychosis with social context. Can J Psychiatry 58, 52–58 (2013).

Schmidt, S. J., Mueller, D. R. & Roder, V. Social cognition as a mediator variable between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: empirical review and new results by structural equation modeling. Schizophr Bull 37, 41–54 (2011).

Goldberg, R. W., Rollins, A. L. & Lehman, A. F. Social network correlates among people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J 26, 393–402 (2003).

Thornicroft, G. et al. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 373, 408–15 (2009).

Üçok, A. et al. Employment and its relationship with functionality and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: EGOFORS Study. Eur Psychiatry 27, 422–425 (2012).

Howes, O. D. & Murray, R. M. Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet 383, 1677–878 (2014).

Bleuler, E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. (New York: International Universities press, 1950).

Lavelle, M., Healey, P. G. & McCabe, R. Nonverbal Communication Disrupted in Interactions Involving Patients With Schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 39, 1150–1158 (2013).

Lavelle, M., Healey, P. G. & McCabe, R. Nonverbal Behavior During Face-to-face Social Interaction in Schizophrenia: A Review. J Nerv Ment Dis 202, 47–54 (2014).

Del-Monte, J. et al. Nonverbal expressive behaviour in schizophrenia and social phobia. Psychiatry Res 210, 29–35 (2013).

Hari, R. & Kujala, M. V. Brain basis of human social interaction: from concepts to brain imaging. Physiol Rev 89, 453–479 (2009).

Chartrand, T. L. & Bargh, J. A. The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol 76, 893–910 (1999).

Lakin, J. L. & Chartrand, T. L. Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychol Sci 14, 334–339 (2003).

Chartrand, T. L. & Lakin, J. L. The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annu Rev Psychol 64, 285–308 (2013).

Marsh, K. L., Richardson, M. J. & Schmidt, R. C. Social connection through joint action and interpersonal coordination. Top Cogn Sci 1, 320–339 (2009).

Schmidt, R. C., Morr, S., Fitzpatrick, P. & Richardson, M. J. Measuring the Dynamics of Interactional Synchrony. J Nonverbal Behav 36, 263–279 (2012).

Hove, M. J. & Risen, J. L. It's all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony in-creases affiliation. Social Cognition 27, 949–960 (2009).

Bernieri, F. J. & Rosenthal . [Interpersonal coordination: Behavior matching and interactional synchrony.] Fundamentals of nonverbal behavior. Studies in emotion & social interaction R. S. [Feldman, R. & Rime, B. (Eds.)] [401–432] (Cambridge University Press, New Work, 1991).

Bernieri, F. J. Coordinated movement and rapport in teacher-student interactions. J Nonverbal Behav 12, 120–138 (1988).

Wiltermuth, S. S. & Heath, C. Synchrony and cooperation. Psychol Sci 20, 1–5 (2009).

LaFrance, M. Nonverbal synchrony and rapport: Analysis by the cross-lag panel technique. Soc Psychol Quart 42, 66–70 (1979).

Feldman, R., Eidelman, A. I. Maternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant-mother and infant-father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: The role of neonatal vagal tone. Dev Psychobiol 49, 290–302 (2007).

Shockley, K., Santana, M. V. & Fowler, C. A. Mutual interpersonal postural constraints are involved in cooperative conversation. J Exp Psychol Human Percept Perform 29, 326–332 (2003).

Neda, Z., Ravasz, E., Brechet, Y., Vicsek, T. & Barabasi, A. L. The sound of many hands clapping. Nature 403, 849–850 (2000).

Dumas, G. et al. The human dynamic clamp as a paradigm for social interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 11, 3726–3734 (2014).

Varlet, M. et al. Impairments of social motor coordination in schizophrenia. PLoS ONE 7, e29772 (2012).

Del-Monte, J. et al. Social motor coordination in unaffected relatives of schizophrenia patients: a potential intermediate phenotype. Front Behav Neurosci 7, 137 (2013).

Schmidt, R. C., Fitzpatrick, P., Caron, R. & Mergeche, J. Understanding social motor coordination. Hum Mov Sci 30, 834–845 (2011).

Maxfield, L. Attention and semantic priming: a review of prime task effects. Conscious Cogn 6, 204–218 (1997).

Schröder, T. & Thagard, P. The affective meanings of automatic social behaviors: three mechanisms that explain priming. Psychol Rev 120, 255–280 (2013).

Over, H. & Carpenter, M. Eighteen-month-old infants show increased helping following priming with affiliation. Psychol Sci 20, 1189–1193 (2009).

Schmidt, R. C. & Turvey, M. T. Phase-entrainment dynamics of visually coupled rhythmic movements. Biol Cybern 70, 369–376 (1994).

Leighton, J., Bird, G., Orsini, C. & Heyes, C. M. Social attitudes modulate automatic imitation. J Exp Soc Psychol 46, 905–910 (2010).

Iacoboni, M. Neurobiology of imitation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19, 661–665 (2009).

Niedenthal, P. M., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S. & Ric, F. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception and emotion. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 9, 184–211 (2005).

Condon, W. S. & Ogston, W. D. Sound film analysis of normal and pathological behavior patterns. J Nerv Ment Dis 143, 338–347 (1966).

Kupper, Z., Ramseyer, F., Hoffmann, H., Kalbermatten, S. & Tschacher, W. Video-based quantification of body movement during social interaction indicates the severity of negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 121, 90–100 (2010).

Doyen, S., Klein, O., Pichon, C. L. & Cleeremans, A. Behavioral priming: it's all in the mind, but whose mind? PLoS One 7, e29081 (2012).

Shanks, D. R. et al. Priming intelligent behavior: an elusive phenomenon. PLoS One 8, e56515 (2013).

Rizzolatti, G., Fabbri-Destro, M. & Cattaneo, L. Mirror neurons and their clinical relevance. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 5, 24–34 (2009).

Trémeau, F. et al. Facial expressiveness in patients with schizophrenia compared to depressed patients and nonpatient comparison subjects. Am J Psychiatry 162, 92–101 (2005).

Brüne, M., Abdel-Hamid, M., Sonntag, C., Lehmkämper, C. & Langdon, R. Linking social cognition with social interaction: Non-verbal expressivity, social competence and “mentalising” in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Behav Brain Funct 5, 6 (2009).

Arueti, M. et al. When two become one: the role of oxytocin in interpersonal coordination and cooperation. J Cogn Neurosci 25, 1418–1427 (2013).

Borgeat, F., O'Connor, K., Amado, D. & St-Pierre-Delorme, M. È. Psychotherapy Augmentation through Preconscious Priming. Front Psychiatry 4, 15 (2013).

Minkowski, E. La schizophrénie. Psychopathologie des schizoïdes et des schizophrènes (Payot, Paris, 1927).

Rumke, H. C. Das Kernsyndrom der Schizophrenie und das ‘Praecox-Gefuhl’. Zentralblatt gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 102, 168–169 (1941).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders. 4th ed. (American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 2000).

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. B. W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). (American Psychiatric Press Inc, Washington, DC, 1996).

Krebs, M. O., Gut-Fayand, A., Bourdel, M., Dischamp, J. & Olié, J. Validation and factorial structure of a standardized neurological examination assessing neurological soft signs in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 45, 245–260 (2000).

Gupta, S. et al. Neurological soft signs in neuroleptic-naive and neuroleptic-treated schizophrenic patients and in normal comparison subjects. Am J Psychiatry 152, 191–196 (1995).

Walther, S. & Strik, W. Motor symptoms and schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology 66, 77–92 (2012).

D'Agati, E., Casarelli, L., Pitzianti, M. & Pasini, A. Neuroleptic treatments and overflow movements in schizophrenia: are they independent? Psychiatry Res 200, 970–976 (2012).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 13, 261–76 (1987).

Srull, T. K. & Wyer, R. S. The role of category accessibility in the interpretation of information about persons: Some determinants and implications. J Pers Soc Psychol 37, 1660–1672 (1979).

Rosenblum, M. G., Pikovsky, A. S., Schäfer, C., Kurths, J. & Tass, P. A. [Phase Synchronization: From Theory to Data Analysis.] Handbook of Biological Physics [Moss, F. & Gielen, S. (Ed.)] [279–321] (Elsevier Science, 2001).

Oullier, O., de Guzman, G. C., Jantzen, K. J., Lagarde, J. & Kelso, J. A. S. Social coordination dynamics: Measuring human bonding. Soc Neurosci 3, 178–192 (2008).

Batschelet, E. Circular statistics in biology (Academic Press, London and New York, 1981).

Bakeman, R. Recommended effect size statistics for repeated measures designs. Behav Res Methods 37, 379–384 (2005).

Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 1988).

Acknowledgements

This experiment was supported by a grant from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Project SCAD # ANR-09-BLAN-0405-03) and the European Union's Seventh Framework Program (FP7 ICT 2011 Call 9) under grant agreement n° FP7-ICT-600610. We express our gratitude to the patients and their family for participating in this research and thereby made it possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R., R.N.S., L.M., J.D.M., R.C.S., M.V., B.G.B., J.P.B. and D.C. contributed to the study design. D.C., J.D.M., R.N.S. and S.R. recruited and assessed the patients. R.N.S. and S.R. performed the statistical analysis. S.R. and R.N.S. wrote the first draft. S.R. and R.N.S. prepared the final manuscript, with feedback from the other authors.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Set-up and experimental material details

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Raffard, S., Salesse, R., Marin, L. et al. Social priming enhances interpersonal synchronization and feeling of connectedness towards schizophrenia patients. Sci Rep 5, 8156 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08156

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08156

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.